One of the first governors to push back against the Medicaid expansion was Arizona Governor Jan Brewer. Brewer vigorously opposed Obamacare for nearly three years. However, after the Court upheld the law, and gave states the option to opt into the Medicaid expansion, Brewer pulled a 180, and supported joining Obamacare. In a bizarre tactic, Brewer decided to veto every bill until the state legislature voted to opt in. Ultimately, the Arizona legislature gave Brewer what she sought, and accepted the expansion.

This sudden reversal in Arizona is all the more unexpected in light of the fact that it was originally Brewer’s opposition to Obamacare that may have back the government into a corner where it could not win on the Medicaid issue in NFIB v. Sebelius. As I discuss in Unprecedented, it was a letter that Brewer sent to HHS in March 2010 asking to opt-out of part of the expansion which helped seed the government’s defeat.

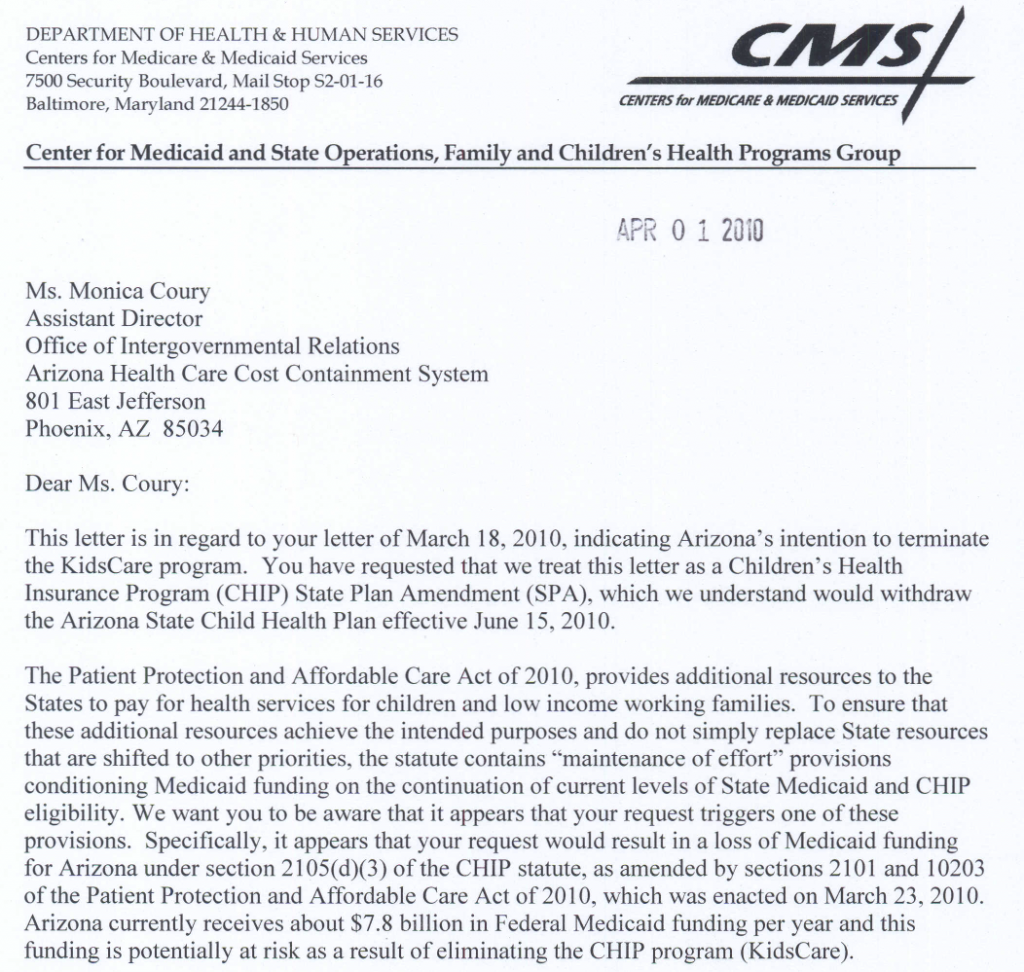

Five days before the Affordable Care Act was signed into law Jan Brewer notified the Department of Health and Human Services that it intended to terminate its participation under the KidsCare program. This program, commonly known as CHIP, was one aspect of the Affordable Care Act’s expansion that provided additional funding to the states to provide health insurance for children.

One week after the Affordable Care Act became law, HHS responded with an ominous and pointed letter: “In order to retain the current level of existing funding, the state would need to comply with the new conditions under the ACA.” This observation was followed by a warning: “We want you to be aware that it appears that your request . . . would result in a loss of [all] Medicaid funding for Arizona.” If Arizona opted out of CHIP, it could stand to lose almost $8 billion in Medicaid funding. That would probably obliterate the state’s budget.

The HHS letter to Arizona contained a not-too-veiled threat of what would happen to other states that did not go along with the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of Medicaid funding. To Arizona, there was no real choice.

Though this letter was not attached as an exhibit to the Supreme Court briefings, and had only been referenced in a single footnote in a motion submitted to Judge Vinson in district court in Florida, Paul Clement mentioned it at just the right moment during oral argument.

Citing this letter, Clement told the Court that what made this expansion so coercive was that Congress was tying “the states’ willingness to accept these new funds . . . to their entire participation in” Medicaid. In other words, turning down the new funds would result in opting out of the entire program, including the old funds.

The Solicitor General was pressed on this letter repeatedly by Justices Roberts, Kagan, and Breyer. All three wanted to know whether the Secretary would in fact take away all of a state’s funding for not participating in the expansion. Verrilli would not state whether HHS maintained that they had the power to revoke all funds, only saying that she would not exercise this power.

Justice Breyer, noting that Clement had said that the secretary “would do it” and withdraw the funding, asked “I would like a little clarification.” Then, Justice Scalia asked if the secretary had the power to withdraw the funding. Verrilli, begrudgingly admitted that “it is possible.” But, he continued, “I’m not willing to give that away.” In other words, he would not concede that fact.

Kagan would not accept that and asked why Verrilli was not “willing to give [that] away.” Breyer chimed in. “What’s making you reluctant?” Verrilli, with a slight chuckle, replied, “I’m not trying to be reluctant.” He chuckled because he knew from the outset that he was not going to answer the question posed to him.

Scalia interrupted him. “I wouldn’t think that is a surprise question.” The solicitor general was not unprepared. Rather, the United States made a conscious choice not to answer the question. He told the justices, “I’m trying to be careful about the authority of the secretary of Health and Human Services and how it will apply in the future.” Verrilli represented the interests of the United States. He could not pin the government into a position that would bind it in the future. More precisely, HHS would not give that power up, so he could not make such a representation in Court. The Solicitor General lacked the authority to answer that question. Unfortunately, the letter, drafted over two years earlier–and likely not vetted by a full legal review–made this representation. Verrilli’s evasion served to inflame the concerns of Roberts, Breyer, and Kagan—the very justices who would soon vote against him on the constitutionality of the Medicaid expansion. HHS would not disclaim that power, so the Court did it for them.

Amazingly, the legal battle over Obamacare in Arizona is still not over. Today the Goldwater Institute filed suit, asserting that the vote to expand violated the Arizona Constitution. The Arizona Constitution requires a two-thirds majority to pass a new tax increase. The suit alleges that the vote to expand medicaid included a new tax, which was not backed by a 2/3 majority. In a fitting dose of déjà vu, supporters of the expansion say it is a “fee,” not a tax. It’s unclear if any saving construction will be applied.

Cross-Posted at JoshBlackman.com.