In the summer of 2006, when some legal scholars feared that President Bush and the Republicans were so powerful that Bush had a king-like status, Steve Calabresi and I published a comment in the Yale Law Journal that pointed out that the existing political science literature had understated the degree to which there typically was a backlash against the party of the president. We showed that the usual erosion of support extended, not just to seats in the House and Senate, but to the states.

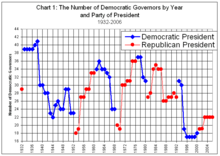

When one adds all gubernatorial races to the analysis, as we do in Figures 1 and 2, backlash against the President's party in state races during a President's term is actually stronger overall than the coattail effect in the presidential election year. To be more specific, we find that four years after a party wins a presidential election, it holds on average three fewer statehouses than it had before it won the presidential election. Perversely, winning the presidency seems to lead very shortly to losing power in the states. Since 1932 there have been eight changes of party control of the White House (1933, 1953, 1961, 1969, 1977, 1981, 1993, and 2001). In every instance but one, the party that seized the White House held more governorships in the year before it took office than in the subsequent year it lost the presidential election. The only exception is that in 1980, Republicans held four fewer governorships than they held in 1992, immediately before the Republicans were voted out of the White House. Similarly, of the eleven Presidents since 1933, every one except two, Kennedy and Reagan, left office with fewer governorships than his party had before he took office, and Kennedy served less than three years. Figure 1 shows this pattern.

click to enlarge

Note that the number of Democratic governorships tends to rise during Republican administrations and fall during Republican administrations.

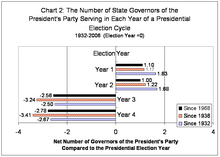

click to enlarge

Figure 2 shows that the coattail effect of winning the presidency is only an increase of 1 governorship over the number in the presidential election year. By the last year of the presidency, the president's party has lost that seat and 3 more governorships.

During the Clinton administration, Clinton was criticized for losing so many seats in Congress and losing so many governorships. Yet that was more or less par for the course. And Calabresi and I were not at all surprised to see large Republican losses in the 2006 election (the normal losses had been avoided in 2002 by 9/11, much as the normal losses were avoided in 1962 by the Cuban missile crisis).

Now the process seems to be repeating today. President Obama's drop in popularity may be slightly larger than for most Democratic presidents early in their terms, but the process is a normal one. Further, while the contests for state governorships may be decided by local issues, the atmosphere is one in which the Democrats will be blamed for the perceived faults of Obama, yet this process is entirely normal.

Presidents make decisions and do or don't do things that make people angry or disappointed and they take out their disappointment on the party of the sitting president — what we call the Lightning Rod Effect. The effect is usually larger than the president's coattail effect in his election year and can be shown even in the races for state offices.