Oh heck, it’s late on a Saturday night, so perhaps Eugene will forgive me … a commenter mentions “roast German shepherd.” Sounds random; actually it cost me my first paid time card job. I was a high school student in Claremont CA, early 1970s, hired as a bus boy and dish washer at Pomona College, in the dining hall. Note the bus boy … for a college dining hall.

As it happens (and this has nothing to do with German shepherds), this particular dining hall has one of the two or three Jose Clemente Orozco murals in the United States, painted during the Depression – a magnificent two or three storey high nude study of Prometheus bringing down the fire from heaven. Unfortunately the trustees couldn’t agree to a full nude and Orozco, rather than stick on a fig leaf, left the outlines of the penis and stopped. A friend from high school, a couple of years older than me but very talented – he was working as an illustrator at Disney Studios in high school – but very weird, really weird, sneaked in one night, after studying the painting and doing extensive research on tints and aging of tints, etc., and finished the job. He followed the outlines Orozco left behind – but later the college, if I remember correctly, had it redone because apparently, in an effort to try and get past the trustees, Orozco had made the member absurdly inadequate for the Fire-Bringer, if I recall the account correctly (I had left Claremont by then).

Anyway, the students of Pomona College were the most obnoxious group of young people I had ever met, even in the midst of the gentle folk era and all that. You had to have been their bus boy to figure that out. My duties after a few months included putting up the marquee for dinner. One day I put up Roast German Shepherd as the entree. Giving into student demands, I was fired the next day. The end.

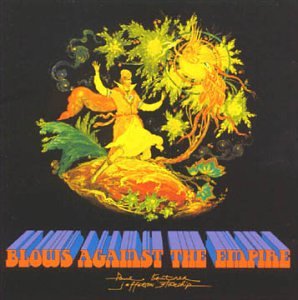

Below the fold, I am indulging myself and re-posting a reminiscence taken from my now abandoned personal blog, loosely constructed around the re-release of an album from that period, Blows Against the Empire.

The Jefferson Starship

From my personal blog, 2005:

This post is decidedly off-topic and awkwardly confessional. I happened to notice that the remastered CD of Paul Kantner/Jefferson Starship’s 1970 album Blows Against the Empire has been reissued.

And I promptly bought a copy. I don’t ordinarily try to recover all the pop and rock stuff of my youth – Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks is an exception – and I’ve mostly moved over to classical music, early baroque especially, and stuff that I’m interested in as a bad amateur cellist – I’ve more or less just finished learning a lovely gamba sonata transcribed for cello by Buxtehude, and I’ve worked my way through several Corelli violin sonatas transcribed for cello. Im about to take up the second of Domenico Gabrielli’s cello sonatas, in A major – it being some of the earliest music ever written for cello, around 1685 or so. It’s not that I don’t still like the music of my young days – I do – but I hate wallowing in it very much, and when I listen to pop, I try to make it at least within the past ten or fifteen years, a lot of alt country, the great Buddy Miller and some Alison Kraus.

Still, I’m amazed to find, thirty five years later, that I pretty much remember every word, pause, phrase, stammer, and guitar note of that exhilirating, peculiar album. Or maybe not – I must have listened to it an easy thousand times, as I hope eveyone does sometime, somewhere in their youth with goofy popular songs.

I ran across it when I was thirteen years old – too young, even in Claremont, California, a then-radicalized, countercultural college town in southern California, to really be part of the sixties. I saw it through a child’s eyes – which is to say, I didn’t notice it especially, and came of age late enough to feel a certain cringe of embarrassment for people who had been genuine young adults in time for the Summer of Love. I still cringe for them – and I came of age in the cringeable seventies, so heaven help me. But as a devout Mormon kid who eventually went on a Mormon mission to Peru before eventually dropping out of the Mormon church, I was counter-cultural to both the culture and the counter-culture. None of it was really me – I hung out with hippie kids and grew my hair long, but never drank or did drugs. I recall my 16th birthday party, a surprise party for me – in which everyone but me got so wasted I spent the party taking care of sick and bad tripping friends. My girlfriend in those years was also a sort of hippie girl – and a devout Christian Scientist who likewise hung out with the wasted kids but never did it herself. (As a parent today of a thirteen year old girl, I can’t imagine wanting my daughter hanging out at sixteen with a kid like me, but there you are.)

(Sometime in the early 1970s, I took L into Los Angeles to a staging at the Mark Taper Forum of two one act Brecht pieces, the very decadent (L was genuinely shocked, not at the sexuality, but at the sheer stunning depravity and cynicism of it; hard to imagine any Claremont teen today having a reaction like that to any stage play, but it was like a kick in her gut) The Mahagonny Singspiel and the austere, revolutionary-reactionary, deeply Stalinist The Measures Taken. We were sixteen and in love – she was beautiful, really beautiful and not just in my memories, boyish figured and thick dark hair that fell to her waist. I loved so much to be with her, we were the only adolescents in that serious theatre audience of adults, and as I look back I see her as the adults saw us, the Los Angeles doctors and their wives, the professors, the Hollywood people, the theatre people, the cultural crowd of LA, watching a pair of kids who had eyes only for each other, as they, the grownups, went through the years in which the culture celebrated divorce and affairs and drugs even among the haute bourgeoisie.)

(I paid for that theatre excursion working my first real job, as a busboy at sixteen in the Pomona College cafeteria – alongside the black youths who came to work in the kitchens of the college – in a dining hall decorated with one of the two or three murals by the Mexican muralist Jose Clemente Orozco, a magnificent three story nude of Prometheus bringing the fire down from heaven – the students annoyed me so much, so spoiled, that I got fired from that job for one day posting as the dinner entree, “Roast German Shepherd” – no sense of humor.)

But this Jefferson Starship album had everything I could ever want as the odd kid I was – a science fiction opera based on stories I had known and loved for years by Robert Heinlein, a theme about a bunch of drugged out hippies stealing a starship and taking off for Eden – echoes of many sci-fi books of my youth and indeed a couple of Star Trek episodes from the period – raucous, cutting lyrics all about the betrayal by Amerikkka and all that stuff, and the driving, irreplaceable electric guitars of Jerry Garcia. As I read the reviews and commentary today, I understand the cultural and political history that I didn’t understand then – the hippie feeling of utter betrayal by bourgeois America, the escapism, the anger over the collapse of the Haight and flower power social project, the desire to cut and run as the hippie thing didn’t seem, by 1970, to be working out as desired. When I discovered it a couple of years later, once I reached high school, it just seemed angry and edgy, and suited my mood.

Although the individual musical performances are often terrific – Jerry Garcia on lead guitar on Starship, Jack Casady on bass, Jerry Garcia on pedal steel guitar, and Jorma Kaukonen on guitar – the music is not actually very good. Well, not quite – the love song Have you seen the stars tonight, written with the help of David Crosby, is quite lovely, a keeper. But as music, it is just a couple of endlessly repeated chords that provide a sort of chanting background for the lyrics. It rises or falls on the lyrics, all those images of departing for a whole different place where no one in authority will bug you. There’s an intense energy to it all, but without Jerry Garcia and Jorma Kaukonen redeeming it, there wouldn’t be much to it musically.

(While a fan, I was never a Deadhead. Yet I know have an inkling that Garcia is how I would ideally like to play the … cello. This is not as whacko as it sounds – I have around here someplace a lovely gamba album of suites by Sainte-Colombe, by a young Israeli gamba player, Hille Perl; she dedicated it to Jerry Garcia, which struck me when I first bought the album as the silliest thing ever, for the stately ancient French music of Couperin and Marais. Yet after a while, I grasped what she meant – there is something about the guitar work of Garcia, his ability to take a percussive electric instrument and give it the lyric quality of the violin or cello that is something I wish I had as a cellist.)

(Added: in the last few months, in 2010, I have become obsessed with that Hille Perle album of Sainte-Colombe, especially track 4, La Conference, I don’t know why, but I play it over and over. I think maybe I would have been happiest playing the viol da gamba, even more than the cello. I don’t truly care about the cello repertoire past Mozart. There. I’ve said it. Also, I think that Pandolfo’s gamba version of the Bach cello suites is truer to the music than any cellist’s rendition I’ve heard. Sue me.)

(And, for that matter, I found a transcription note for note of Santana’s La samba pa ti and have been learning to play it, bit by bit, on the cello – with an eye to playing it on my Yamaha electric cello which, with an amplifier and the gain turned up high, can achieve a very electric guitar sound to it.)

What astonishes me, though, is to read through the comments on Amazon and various web sites about the re-release of Blows Against the Empire and grasp just how topical many of these aged ex hippies think it still is. Granted, I’ve moved a long way from the seventies left – and in one sense was never really there, and was never part of the sixties, even just by a few years. (One of the peculiarities of generational culture is that the shifts are not smooth – my wife, only two years older than me, was a sixties person because of the fact that she was in college while the Vietnam war was still on. It made a difference to be in college then, as distinct from merely being in the first couple of years of high school. The bombing of Cambodia was a big deal, as I recall, at my high school, but that was because it was a college town – if you were in college then, it was a much bigger deal.) But there are a lot of people out there for whom these years, now, really are the War, the betrayal of – well, what, exactly? Nostalgia, so far as I can tell. But then I wasn’t there in the sixties, except as a disconnected child. Maybe you had to be there, as a semi-grownup.

But, finally, this album was the first occasion in my life for writing what I suppose was juvenile cultural criticism. I wrote a long paper on it for an english class in high school. I recall that I talked about escapism, mostly, and how these people seemed to have given up the ideal of engagement. I talked a lot about Heinlein and his libertarian philosophy – I only now found out that the album was nominated for a Hugo Award. I don’ t think I talked about the anger in the album – probably because I took it entirely for granted.

(This was in a class where we read Hamlet one semester and Ulysses the next, and could pick one foreign classic for our own – Stendhal’sRed and Black, naturally, which I have reread almost without exception every year since I was fourteen – and then one contemporary poem or essay or what have you. I had discovered Blaise Cendrars (“if it weren’t for the life I’ve led, I surely would have committed suicide”) and Albert Camus of The Fall and The Rebel, but not yet Rene Char and the astonishing Leaves of Hypnos. And Alfred Jarry and Friedrich Durrenmat and Bertolt Brecht, and my girlfriend had given me The Pillow Book. And a slightly later girlfriend, a much older woman who subsequently went off with the guitarist Mason Williams, searched through old LA porn shops to present me with original banned editions of Henry Miller – though I never had the faintest interest or patience, then or now, with Kerouac and the Beats or really much of 20th century American literature. The great retelling of Arthurian legend, Thomas Berger’s Arthur Rex, was not published until 1979.)

It’s a fresh wind that blows against the empire, indeed.