My old friend Matt Harrington now runs a Center for the Study of Common Law at the University of Montreal Law School and he blessed me with an invitation to speak a program last week on common law as a regulatory system and the interaction of common law with regulation. My job was to add a third dose to that, which was competition as a regulatory system, especially for consumer protection, and the interaction of markets, common law, and regulation. One of the observations I made was that auto safety was something that consumers seemed to place a value on, as evidenced by advertising, especially brands such as Volvo that built its name on safety (also the market losses Toyota suffered in recent years because of its safety issue). My argument was that the market itself provides powerful incentives to provide safe products. I also acknowledged that there can be market failures but that the first line of response should be common law (warranty, tort, fraud), and only as a last resort should we bring in regulation, which is costly, prone to capture and interest-group distortion, and unintended consequences.

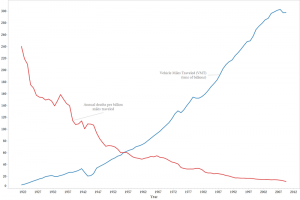

During the discussion the question came up, essentially, “Well, if safety is produced by the market, why did Washington create the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) in 1970?” And it was pointed out that since NHTSA was established, traffic fatalities per mile driven are about 20% as they were at the time. It was also noted that prior to Henningson v. Bloomfield Motors (1960) warranty terms on cars sucked. And grisly stories were told about automobile crashes in the 1960s and the heroism of Ralph Nader and “Unsafe at Any Speed.”

So I was curious what the data showed and I found this chart (

The chart pretty much speaks for itself, I think. Obviously by itself this doesn’t demonstrate that litigation and regulation didn’t or couldn’t have an impact. It does pretty clearly show to me, however, that cars were getting safer at a very rapid rate prior to the expansion of products liability and certainly prior to regulation. And it also seems likely that safety would have continued to improve from the forces of competition even without liability and regulation. Of course there are multiple confounding sources. The forced introduction of smaller cars through mileage regulations likely slowed the decline may have slowed the decline in highway fatalities over time, reversing some of the gains from whatever source. And it is difficult to determine the marginal effect of market forces versus liability and regulation–or whether the overall marginal effect of liability and regulation has been positive or negative, once the costs and unintended consequences are considered.

Update: I changed the point about the potential negative safety impact of smaller cars on safety to avoid distraction from the central point of the post. That’s a contested issue in the literature and I don’t need to get into that particular point here. Ditto for the unintended consequences of safety laws (such as mandatory seat belt laws) on pedestrian and cyclist deaths.