When one of my nephews fell ill with a strange pneumonia-like illness as a boy in the 1980s, his mother was told he had something called “Valley Fever.” My sister and her family lived in Bakersfield, California, and it was something I had heard of – my parents had lived there for a couple of years when I was young – but had more or less forgotten. He got better, but I’m told still carries the fungus in his lungs.

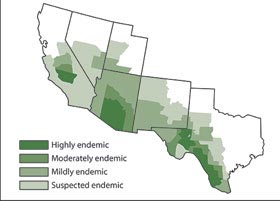

Coccidioidomycosis used to be regarded as a rare disease, limited – I remember the maps from the 1970s and 80s – to the areas around Bakersfield, CA (the San Joaquin Valley) and a completely different location around Pima, AZ. That was it. The disease is caused by microscopic spores in the soil – dry and dusty soil in these locations – that, once disturbed, can float airborne and lodge in the moist environment of the lungs – or many other places in the body. My nephew probably picked up the disease playing the Bakersfield dirt at his house or at school. Doctors were able to treat his follow-on medical problems – in his case, pneumonia and lung conditions – but they had no treatment and no prevention for the spores themselves.

Later on, in the late 1990s, the head of a small but relatively cash-rich foundation in New York contacted me, wanting suggestions on a back channel for what kinds of new initiatives the foundation might undertake. He wanted to something exciting, exotic, and foreign. I told him he had a sizable amount of money, but probably not enough to make it worth initiating the infrastructure for a new development project abroad. As an alternative, I suggested that he do something closer to home – something that would have impact because no one else would bother. I said, fund and give infrastructure and organization to finding a prevention and cure for Valley Fever.

He said, valley what? I explained all about it. I told him about my nephew, and pointed out that the many, many of the cases were found in very poor agricultural field workers, Mexican Americans, and there was simply no attention to this kind of orphan disease. But also oil workers, construction workers, anyone pretty much who worked outside earth, soil, and dust – an awful lot of people in the San Joaquin Valley. But, I said, my sister in Bakersfield – a nurse – had told me that the number of cases in the Bakersfield area was rising year by year, and in areas farther out than thought to be this soil-based disease’s range. She thought it would turn out to be a much bigger problem than anyone imagined in the late 1990s.

The foundation passed on my suggestion and funded some art installations in New York and some micro finance somewhere abroad. All good, but meanwhile my sister was right. The disease has turned into something the Centers for Disease Control have called a “silent epidemic” and it turns out that the geographic range of the spores is much, much greater than previously imagined. The New York Times has an excellent article on the belated recognition that Valley Fever is a serious health problem in the dry dusty areas of the Southwest, especially among field workers in agriculture but, as it turns out, well beyond them, with no cure and in many cases utterly crippling and life-threatening repercussions. It’s in today’s paper, “A Disease without a Cure Spreads Quietly in the West,” by Patricia Leigh Brown.

Coccidioidomycosis, known as “cocci,” is an insidious airborne fungal disease in which microscopic spores in the soil take flight on the wind or even a mild breeze to lodge in the moist habitat of the lungs and, in the most extreme instances, spread to the bones, the skin, the eyes or … the brain.

The infection … is striking more people each year, with more than 20,000 reported cases annually throughout the Southwest, especially in California and Arizona. Although most people exposed to the fungus do not fall ill, about 160 die from it each year, with thousands more facing years of disability and surgery. About 9 percent of those infected will contract pneumonia and 1 percent will experience serious complications beyond the lungs. The disease is named for the San Joaquin Valley, a cocci hot spot, where the same soil that produces the state’s agricultural bounty can turn traitorous.

The immediate impetus for the Times story is a judge’s order to move the inmates of two state prisons that are in the area of the disease:

The “silent epidemic” became less silent last week when a federal judge ordered the state to transfer about 2,600 vulnerable inmates — including some with H.I.V. — out of two of the valley’s eight state prisons, about 90 miles north of here. In 2011, those prisons, Avenal and Pleasant Valley, produced 535 of the 640 reported inmate cocci cases, and throughout the system, yearly costs for hospitalization for cocci exceed $23 million.

Part of the difficulty in diagnosing and treaty Valley Fever is that “cocci is ‘a hundred different diseases’ … depending on where in the body it nests.” It might result in pneumonia in the lungs, meningitis in the brain, still other things in the spinal cord, and so on. The reason for little action on the three fronts of diagnostic tests, vaccines, and treatments is the usual problem with orphan diseases – not enough of a market. With 20,000 cases reported across the Southwest last year – almost certainly an undercount – and the number rising, while the geographic incidence is turning out to be much more widespread across the Southwest than thought – maybe that will change. Maybe not:

[T]here is still no cure, and research on a fungicide and a potential vaccine have been stalled by financing issues. One company, Nielsen Biosciences Inc., has developed a skin test to identify cocci but has not yet been able to make it financially viable.

The CDC’s map of Valley Fever incidence, 2013:

Comments are closed.