Naturally, the first question everyone wants to know is isn’t the need for bankruptcy reform just a response to “too much” credit card credit. In fact, this argument not only lacks empirical foundation, it lacks sould economic theory to support it.

First, the argument doesn’t make much sense from an economic perspective. Unless credit cards have somehow removed the borrowing constraint on individual credit (and no one has provided any evidence that it has), there would be no reason to believe that credit cards would increase overall household indebtedness.

Instead, economic theory would predict that the primary effect of the introduction of credit cars would be to shift around patterns of consumer credit use, by substituting credit card debt for other less-attractive forms of credit, such as pawn shops, personal finance companies, and retail store credit (such as from appliance and furniture stores). In fact, this is what the evidence indicates has actually happened.

Credit cards have not worsened household financial condition, because although consumers have increased their use of credit cards as a borrowing medium, this increase represents primarily a substitution of credit card debt for other high-interest consumer debt. Although this may seem irrational at first glance given the “high” interest rates charged on credit cards, consider that for consumers the alternatives may include pawn shops, personal finance companies, retail store credit, and layaway plans, all of which are either more costly or otherwise less attractive than credit cards.

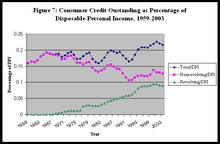

Thus, while credit cards may not be ideal in some absolute terms, their growing popularity reflects the relative attractiveness of credit cards versus these other forms of credit. Credit cards are also generally less expensive for lenders to issue, which is reflected in the overall price of credit cards relative to these other forms of credit. The result, therefore, has not been to increase household indebtedness, but primarily to change the composition of debt within the household credit portfolio. Figure 7, from my article “An Economic Analysis of the Consumer Bankruptcy Crisis” (Forthcoming this year in the Northwestern Law Review) illustrates the nature of this substitution:

Source: Federal Reserve Board and Bureau of Economic Analysis

As this chart indicates, the growth in revolving (credit card) debt has clearly been a substitution from nonrevolving consumer debt to revolving debt, thus leaving overall consumer indebtedness (as a percentage of income) largely unaffected. Revolving debt outstanding has risen during this period from zero to roughly 9% of outstanding debt. Nonrevolving installment debt, by contrast, has fallen from its level of 19% of disposable income in the 1960s, to roughly 12% today. Thus, the increase in revolving debt has been almost exactly offset by a decrease in the installment debt burden. In fact the recent bump in total indebtedness in recent years was not caused by an increase in revolving debt, which has remained largely constant for several years, but by an increase in installment debt, primarily as a result of a recent increase in car loans for the purchase of new automobiles. Thus, there is little indication that increased use of credit cards has precipitated greater financial stress among American households. Because the increase in credit card usage has resulted primarily from a substitution of credit cards for other types of consumer credit, rather than an overall increase in indebtedness.

To the extent that there is some correlation between “high” credit card indebtedness and bankruptcy, but it is questionable whether this supports the causal inference that the credit card debt caused the bankruptcy, rather than the other way around.

First, the correlation between credit cards and bankruptcy may reflect the unique role of credit card borrowing in the downward spiral of a defaulting borrower. Credit cards provide an open line of unsecured credit to be tapped at the discretion of the borrower. Thus, for many debtors credit cards are a “credit line of last resort” to stay afloat to avoid defaulting on other bills. Thus, there may be nothing more than a simple correlation—a debtor confronting a downward spiral may increase his credit card borrowing in the period preceding bankruptcy simply because it is his most easily accessible line of credit. It may appear that because credit card borrowing preceded bankruptcy it also precipitated bankruptcy filing, but if the credit card was being used as a source of credit of last resort, this correlation would not support a causal inference.

Second, a debtor’s increased use of credit cards preceding bankruptcy also may reflect strategic behavior taken in anticipation of filing bankruptcy. Credit card debt is unsecured debt that can be discharged in bankruptcy. By contrast, some unsecured debts are not dischargeable in bankruptcy, and secured debts, such as home and auto loans are minimally affected. For unsecured credit card debt, by contrast, generally the debtor can retain the property purchased with the credit card and discharge the obligation. Given the choice between defaulting on secured or nondischargeable obligations on one hand versus dischargeable credit card debt on the other, the incentive is to use credit cards to finance payment of nondischargeable and secured debt. In fact, empirical evidence shows that although credit card defaults have risen in tandem with bankruptcy filings, defaults on secured home and auto loans have remained steady during this period. Debtors also will have an incentive to “load up” their credit card on the eve of bankruptcy, especially by purchasing goods that will not be classified as “luxury goods and services” but might still be quite expensive and the timing of which might be discretionary. Still others simply spend the money or save in exempt assets rather than pay outstanding bills.

One article by Gross and Souleles (cited in my article), for instance find that in the year before bankruptcy, borrowers significantly increase the use of their credit cards, running up their balances rapidly in the period leading up to bankruptcy. This finding is inconsistent with the predictions of the traditional model, which identify credit cards as a special problem because of the gradual, subconscious, and “insidious” manner in which they accumulate over time. If this is true, then the accumulation of credit card debt should be gradual and spread out evenly over time. The rise in credit card debt rises rapidly and is concentrated in the period immediately preceding bankruptcy suggests that credit card indebtedness does not cause bankruptcy in many cases, but that the debtor is already on the way toward bankruptcy when the credit card borrowing begins, and is either acting strategically or is tapping his credit line of last resort.

It also has been argued that credit cards have contributed to increased bankruptcies through a profligate expansion of credit card credit to high-risk borrowers, especially low-income borrowers. Although often-repeated, empirical studies have failed to support this theory. First, the growth in credit card debt by low-income households primarily reflects a substitution for other types of debt, not an overall increase in indebtedness. In addition, two studies have examined the hypothesis empirically and have found little support. The first study, by economists Donald P. Morgan and Ian Toll concludes, “If lenders have become more willing to gamble on credit card loans than on other consumer loans credit card charge-offs should be rising at a faster rate [than non-credit card consumer loans] . . . . Contrary to the supply-side story, charge-offs on other consumer loans have risen at virtually the same rate as credit card charge-offs.” Thus “suggest[s] that some other force [other than extension of credit cards to high-risk borrowers] is driving up bad debt.”

A second study, by David B. Gross and Nicholas S. Souleles, concludes that changes in the risk-composition of credit card loan portfolios “explain only a small part of the change in default rates [on credit card loans] between 1995 and 1997.” Moreover, if it were true that lower-income households were dramatically increasing their indebtedness through credit card increase then this should be reflected in the debt service ratio for lower-income households. As previously noted, however, this ratio has remained largely constant for lower-income households as with all others.

Increasing use of credit cards may be causing higher bankruptcies, but not in the way suggested by critics of reform. Because credit card credit is unsecured, it easily dischargeable in bankruptcy, which may make people more willing to file bankruptcy. Many older forms of credit were secured, such as furniture and appliance credit. Moreover, it may be that people fell less of a personal obligation to repay credit card debt, as opposed credit from a local merchant. But if these explanations explain what is happening, then it seems like this is an argument for bankruptcy reform, rather than against it.

The bottom line is that the standard argument about the relationship between credit cards and bankruptcy does not appear to be consistent with either economic theory or available evidence.

Comments are closed.