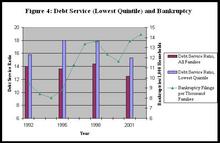

The relationship between the debt-service ratio and bankrutcies holds up when you look at the lowest quintile as well. This belies the claim that the problem is profligate expansion of credit to risky low-income borrowers, which is usually what is referred to in discussing subprime borrowers. Consider this data drawn from the same article:

Again, although there appears to be a loose correlation between changes in the debt service ratio and changes in the bankruptcy filing rate, changes in the debt service ratio of the lowest quintile cannot explain the upward trend in bankruptcy filing rates over the past decade. Thus, whereas the debt service ratio for the lowest income quintile of the population was unchanged between 1995 and 1998, the overall bankruptcy filing rate soared. Similarly, whereas the debt service ratio fell from 1998 to 2001, bankruptcy filings were the same in 1998 and 2001. The debt service ratio of the lowest quintile was also the same in 1992 and 2001, but bankruptcies were much higher in the latter period. In short, changes in the lowest-income sector of society do not explain rising bankruptcy filing rates. Thus, the aggregate debt-service measurements are not concealing some sort of unrecognized distress among poor households.

I have explained the reason for this in an earlier post. There is no indication that the increased competitiveness of lending to lower-income households has changed the household borrowing budget constraint. Instead, it has largely resulted in a switching around of the types of consumer credit. So, for instance, the growth in credit card access by lower-income households has largely just been a substitution from other forms of credit, such as pawn shops, personal finance companies, and retail store credit (remember Williams v. Walker-Thomas?). The increase in competition has increased credit options to low-income borrowers, thereby enabling them to get access to credit on more competitive terms.

This also suggests that the growth in subprime lending is not creating overwhelming debt burdens for low-income households. In fact, by expanding home ownership, subprime lending has made it possible for low-income houesholds to access home equity credit, which has a lower interest rate than other credit alternatives. And while subprime lending is obviously riskier, foreclosure rates average 0.2 percent for prime mortgage loans and 2.6 percent for subprime mortgages, higher but still not that high.

In fact, the biggest differences in household financial condition in America today is not so much by difference in income, but rather differences in homeowners versus non-homeowners. This may come as a shock to critics of subprime lending, but if a person can’t get a mortgage, they still have to live somewhere, and usually that is to rent an apartment. The difference, of course, is that homeownership enables both the accumulation of wealth as well as access to home equity borrowing. Renters, by contrast, are not building wealth and are limited to a motley assortment of consumer credit options. As a result, renters are much more likely to borrow on credit cards, whereas similarly-situated home owners can access a lower-interest home equity loan.

So social engineers may want to be careful about “saving” the poor from the scourge of subprime lending, because by restricting those choices they are likely just pushing them into even less-favorable credit options.

Comments are closed.