Over the past few weeks, I have had two interesting experiences with the fact checking process of the MSM: the New Yorker and the New York Times to be precise. The New Yorker was the first to contact me to fact check Margaret Talbot’s story on Justice Scalia. In order to show that the Justice was exaggerating the history of originalism, the original story contained some questionable claims. I found it interesting, and reassuring, that the fact checkers sought out a professor like me who subscribes to originalism to double check these claims. All the errors I noted were corrected in the final story, though of course this did not unduly affect its overall negative slant. A week later, I was having dinner in Princeton with a group of professors and graduate students after my talk there. When I asked if anyone had seen the article, Keith Whittington (author of

Constitutional Interpretation: Textual Meaning, Original Intent, and Judicial Review) piped up that he had been contacted to fact check it. So not one but TWO originalist scholars had been contacted. Very impressive indeed.

Last week, I was contacted by the NYT to fact check what was going to be said about me in Jeff Rosen’s Sunday Magazine story on the so-called “Constitution in Exile” movement. Like others, I had never heard this phrase until long after it was being used by “moderates” like Cass Sunstein. As the blogosphere is already effectively dismembering the substance of Rosen’s in-depth report on the VLC (Vast Libertarian Conspiracy), I thought I would confine myself to my experience with the Times fact checking process.

Almost all the claims the fact checker wanted to confirm had some sort of minor defect, most of which had nothing to do with the obviously negative slant of the piece. For example, it described Angel Raich as formerly paralyzed; it had the wrong number of states adopting medical cannabis statutes.

One erroneous claim, however, was definitely part of the story’s slant that I was a part of an organized “Constitution In Exile” movement: that the Cato Institute had either paid for or published my book, Restoring the Lost Constitution. This claim was removed from the finished article after I explained that the book had been published by Princeton in its normal acquisition process, but that Cato had assisted me during my university sabbatical year when I wrote the first draft of the manuscript (as I acknowledge in the book). Score one for the fact checking process.

The only accurate but misleading claim that remained was that my “book identifies a series of regulations that he says the courts should consider constitutionally suspect, from environmental laws to laws forbidding the mere possession of ordinary firearms, therapeutic drugs or pornography.”

I knew about the environmental law issue, of course, as I mentioned it to Jeff and offered it in the book as an example of an “unhappy ending” that I think represents an oversight in the original Constitution. Jeff had tried very hard to get me to say what laws would be unconstitutional under my approach. As my approach is presumptive, however, this is hard to answer in the abstract, as the success of any challenge to a particular law will depend a lot on specifics. An analysis of the constitutionality of any particular law would require a lengthy analysis.

So I pointed to the section of my book where I discuss what I think is the unfortunate consequence that some environmental activities would be within the jurisdiction of state not federal regulation. In the book, I offer this as one of the very rare instances in which the Founders did not anticipate a genuine cross-border national problem properly handled at the national level. He ended up using this in his story, of course, as I knew he would—albeit without my disclaimer that I offered this as an example of a bad consequence I would like to see corrected by constitutional amendment (that would pass in a week if the Court ever held Congress to its Commerce Clause power on this issue).

I had to ask the fact checker for the pages where I discuss “firearms, therapeutic drugs, and pornography” as I did not recall having done so. Sure enough all three examples are in one single sentence as illustrations of the sort of pure “possessory” laws that would be suspect under the conception of the state police power that I defend in the book. When I read the fact checker the entire paragraph (he did not have the whole sentence or a copy of the book), I stressed that it applied only to pure “possessory” crimes. I told him that, contrary to what the use of these examples implied, I never claimed that the manufacture or sale of these items could not, constitutionally, be regulated. He said that he would consult with the editors and get back to me. Over dinner, it occurred to me that if they added “mere” possession, this would ameliorate (though not entirely eliminate) the implication that my approach ruled out all regulation. After dinner, the phone rang and the fact checker informed me that the editors had decided to insert the word “mere” in front of possession (without my even suggesting they do so).

What is interesting about having experienced this fact checking process first hand is that, in both cases, there was a sincere effort by the fact checkers to verify suspect claims–claims that really were inaccurate. In each case, where I explained my objections, these claims were then corrected. Yet the overall misleading slant of the NYT story was preserved. None of this is the fact checker’s fault, or even the fault of the fact checking process, which I found to be admirable. With both the New Yorker and NYT, the fact checkers were sincere in their desire to get the facts correct. Both were very impressive and the resulting articles were more accurate as a result.

But an important lesson here is that accurate facts can still be used to compile a highly distorted story like the one by Jeff Rosen, a person I have known and respected for many years—dating back to his very useful student article on the founders’ conception of unenumerated rights. It was out of this respect for Jeff that I gave him a long and candid phone interview last February, but I could tell from the questions what the slant would ultimately be.

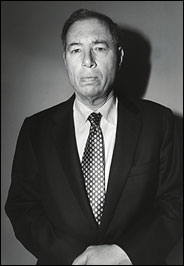

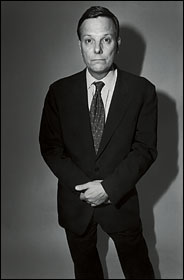

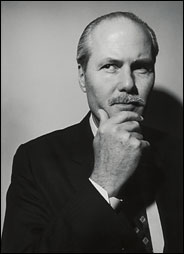

Despite the MSM’s claim to greater accuracy than blogs, fact checkers cannot alter the spin an author can put on what the National Lampoon used to call “true facts”—especially when this is the very spin the editors had in mind when they solicited the article. Apart from the inaccurate constitutional history noted by David, I cannot quarrel with any of the facts reported in Jeff’s piece. They are true, even if the impression given by the story to credulous readers of the New York Times is false. Fittingly, the “accurate but fake” nature of the “Constitution in Exile” story is best illustrated—literally—by the unrecognizable morgue photos of Richard Epstein and Michael Greve—both would be completely unrecognizable to me had I not read who they were supposed to be—and the “Snidely Whiplash” picture of Chip Mellor.

While all were certainly actual photos taken of these three men by the Times photographer, at the same time they all were fake. How fitting.

Comments are closed.