Yesterday, I reviewed some background on damages caps. Today, I want to focus on the effect of damages caps on payouts. Of course, payouts are not the only thing worth studying, as the comments to my first posting reflect. Access to medical services might well be affected by a cap. So might malpractice premiums -- at least that was the hope/expectation of those who proposed caps to deal with the malpractice (premium) crisis. And, don't forget defensive medicine, which affects total spending on health care. But, for right now, I want to focus on actual payouts.

What does past research find about the effect of damages caps? The results are mixed, but most of the studies find that caps do reduce payouts -- typically by between 15% and 35% -- although some find no effect whatsoever. You can find a review of the literature, with references to the underlying studies here, in Section II.

There are at last four different ways of studying how damages caps affect payouts. One can:

1. Compare payouts in states with and without damages caps. This can be done either at a case-level, or using aggregate insurer payouts.

2. Obtain case-level verdicts and estimate how a particular damages cap will affect payouts.

3. Obtain payouts in tried and settled cases from a state without a cap, and estimate how a damages cap will affect payouts.

4. Compare payouts before and after a cap is adopted in a single state or across multiple states.

Each of these approaches has been used by researchers, and each has their own mix of advantages and disadvantages.

For example, the first approach implicitly assumes that all states with caps have the same cap. This is clearly incorrect, as yesterday's posting made clear. So, if a comparison finds no difference in payouts between cap and non-cap states, it might be because caps have no effect on payouts, or it might be because a very restrictive cap in one state had a big effect, but less restrictive caps in other states had little/no effect -- and averaging results across all states with caps obscures the fact that there was a difference in payouts, but only in the state(s) with more restrictive caps.

The second approach looks more straightforward, but it has its own complexities. For example, if payouts don't correspond to verdicts, applying the cap to the verdict gives you a misleading impression of the real impact of the cap. For example, if it turns out that defendants don't actually pay what the jury awards, then a straightforward application of the cap will substantially overstate the cap's impact -- giving the cap credit for "taking away" money that isn't being paid to begin with.

In an earlier article, we found that defendants generally don't pay what juries award -- and the larger the verdict the larger and more likely the "haircut." Overall, only 46% of the amount awarded by juries is actually paid. The most important factor explaining verdict haircuts is the amount of insurance coverage. If the doctor has $500,000 in policy limits, it doesn't seem to matter whether the jury awards $500,000, $1,000,000, or $5,000,000. The insurer will pay $500,000, and that will usually be the end of the dispute. Above-limits payouts are uncommon, and when they occur, they are virtually always paid by the insurer. (More discussion of those subjects is saved for another day).

The third approach, which is the one we use in this paper, has the virtue of relying on actual payouts (instead of verdicts), but one needs to make a series of assumptions in order to do the estimation. The main weakness of this approach (apart from the plausibility of the necessary assumptions) is that it is a static snapshot: it takes cases to which the cap doesn't apply, and assumes the same cases will be brought post-cap. That's a pretty strong assumption -- particularly if what we are interested in is the impact of a damages cap on payouts by defendants. Consider three possibilities:

1. the cap makes some cases insufficiently remunerative, so they are not brought -- decreasing the volume of cases;

2. the cap changes the economics of some (but not all) cases, so some cases are dropped, but other cases( that used to be insufficiently remunerative) are now worth pursuing, and they take the place of the cases that are dropped -- meaning the volume of cases stays the same;

3. the cap makes malpractice cheaper, and so doctors take less care and injure more people -- increasing the volume of cases.

The first two effects are likely to be realized, if at all, in the short-run, while the third is likely to be realized, if at all, in the long-run. It is hard to know how to sort out this issue in the abstract. Even though the third approach will not provide a clear answer as to the dynamic consequences of a non-econ cap on defendant's payouts, it does have one important advantage -- it tell us what the impact of a cap will be from the perspective of the current group of plaintiffs -- and if you're at all interested in the distributional consequences of a cap, that's worth analyzing.

The final approach is the best way to do these kinds of studies, but the data to do so is generally not available. (We anticipate doing one of these studies around 2011, since that is the earliest the necessary data will be available).

Regardless of which approach one uses, there are additional complexities to be dealt with, such as determining when a cap actually went into effect. That problem is harder than one might think: how should one handle a cap while it is under constitutional challenge in the state courts? How should one handle a cap that was in effect for a while, and then struck down? The answer to both questions will depend on one's sense of the factors that influence insurer behavior. For example, to what extent do insurers discount their expectations regarding cap effects by their expectations of when and whether the cap will be upheld? Do they hold up settlement of cases until it is clear whether the cap will be upheld, or settle them with the expectation the cap will be upheld -- or struck down -- or something in-between?

One final difficulty, which is common to all four approaches, is the problem of obtaining data. When money is transferred from defendants to plaintiffs, it is almost always the result of a settlement -- and it is extremely hard to obtain case-level information on settled cases. It is somewhat easier to obtain case-level information on tried cases, but trials are rare, and, as noted above, the jury verdict does not necessarily indicate the actual payout. The most common source of information on jury verdicts (commercial jury verdict reporters) are systematically skewed toward larger verdicts -- and they usually don't contain information on payouts.

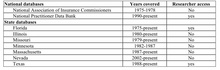

Researchers have used different strategies to address this problem. Some have simply used information on verdicts, while cautioning readers as to the limitations of this approach. Others have obtained information on payouts in tried and settled cases from individual insurers, the National Practitioner Databank, or state closed claims databases. Several states maintain such databases, but not all of them are public. For example, Illinois has a database of all malpractice claims dating back to 1980, but the enabling statute prohibits public release of the information, even if it is de-identified. A slightly dated list of such databases, which is Table 1 in this article, is reproduced below.

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners is working on developing guidelines for states that are interested in creating their own databases. Not surprisingly, one of the flashpoints has been the degree of confidentiality of the reported information. Physician groups have generally opposed public release of the information, even on a de-identified basis. That said, the American Society of Anesthesiologists has used closed claims to identify areas likely to lead to malpractice claims, and to improve the quality of the services they deliver.

In our study we rely on the Texas closed claims database, which includes case-level information on all commercially insured closed medical malpractice claims in which there was a payout > $10,000 nominal. More detailed information is available on cases in which the payout was greater than $25,000 nominal. The database is updated annually, and currently includes the years 1988-2005. The data is here. ("Closed Claim Data"

As my posting from yesterday indicates, the Texas non-econ cap varies from $250,000 to $750,000, depending on the number and type of defendants. The Texas cap is not indexed for inflation.

This post has once again gone on longer than I intended, so I'll just summarize our findings, and provide some more detailed analysis tomorrow. We find that

• The Texas cap reduces the mean (median) "allowed verdict" (the allowable portion of the jury award, plus interest) by 37% (36%). The mean allowed verdict drops from $1.28M to $800k.

• The Texas cap reduces the mean (median) predicted payout in jury verdict cases by 27% (23%). The mean payout drops from $696k to $512k. The reduction in mean payout ($184k) is substantially smaller than the reduction in the mean allowed verdict ($480k). In total, the non-econ cap reduces adjusted verdicts by $156M, but predicted payouts by only $60M.

• Settled cases account for 97.5% of the cases and 95% of the dollars in the dataset. Predicted aggregate payouts in settled cases decline by 18%. The mean settlement payout declines from $313k to $257k. The total reduction in payout is on the order of $780M.

• The non-econ cap has a disparate impact across plaintiff demographic groups, with the larger percentage reductions borne by deceased, unemployed, and (likely) elderly plaintiffs, relative to non-deceased, employed, and non-elderly plaintiffs.

That's enough for today.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Damage Caps and Medical Malpractice VII

- Damage Caps and Medical Malpractice Litigation: VI

- Damage Caps and Medical Malpractice Litigation: V

- Damage Caps and Medical Malpractice Litigation: IV

- Damage Caps and Medical Malpractice Litigation: III

- Damage Caps and Medical Malpractice Litigation: II

- Damage Caps and Medical Malpractice Litigation