|

|

Alexander "Sasha" Volokh

My tour of medieval Europe

Canterbury, England, June 30-July 1, 1999

"The city of Canterbury was the capital of the early Saxon kingdom of Kent, and its Anglo-Saxon name

Cantwaraburg meant 'fort of the dwellers of Kent'....

The famous fale of how Pope Gregory saw the 'angelic Angles' in the slave market [in Rome] is well

known.

This event probably happened in about 586, and it determined Gregory to attempt the conversion of the

heathen Anglo-Saxons.

For this great task he chose Augustine, who was prior of his own monastery at Rome.

There is evidence that Augustine was reluctant to embark upon this arduous task; he accepted only

because Gregory was, as Pope, the 'Vicar of Christ' whose word could not be gainsaid.

Augustine set out for the barbaric northern lands, but on his way through France he was so appalled

by tales of English savagery that he decided to return to Rome.

Gregory would brook no excuses, and Augustine set out once more for the island which lay on the edge

of the world."

Nigel & Mary Kerr, A Guide to Anglo-Saxon Sites (1982), p. 188 (subsequent references to this

source are labeled "Kerr")

Above: St. Martin's church.

The priest tells me this isn't a holy cat.

"This weren't nearly as bad as Augustine had expected.

When he landed he was met not by howling barbarians but by a strong and relatively civilized kingdom

ruled by King Ethelbert.

Though a pagan himself, he was married to Bertha, daughter of Caribert, who was the Christian king of

the region about Paris.

The Venerable Bede tells us in his History that Ethelbert allowed Bertha to practise her

religion, and that she had with her her personal chaplain Bishop Liudhard.

Bede also tells us that: 'There was on the east side of the city a church dedicated to St. Martin

which had been used by the Roman Christians in Britain.

To this church the Queen, accompanied by Bishop Liudhard, came to worship.'

"The little church of St. Martin still stands, but although Roman finds have come from the site, few

would date any part of the structure earlier than the beginning of the 7th century.

The cancel of the present church is of very great antiquity, however, and it is generally accepted

that it was the nave of the original church in which Queen Bertha worshipped.

It is of course very likely that St. Marin's stands on the site of the Roman church mentioned by

Bede.

"After Augustine and his monks landed, King Ethelbert went to talk to them.

Being a somewhat cautious pagan, he declined to meet them indoors, since he feared their 'magic,' so

an open-air conference was held instead.

Augustine was afterwards given leave 'to preach his religion provided he used no compulsion or force

in making converts' -- a nice example of early English fairness!

Having been thus accepted, Augustine set about his work of conversion.

He made great strides, and Ethelbert himself was baptized soon afterwards, probably in St. Martin's

church.

On Christmas Day 597, Augustine is said to have baptized over 10,000 converts in and around

Canterbury."

Kerr, pp. 188-89

Below: Pictures from St. Augustine's Abbey.

Quotes are from St. Augustine's Abbey, the English Heritage

guidebook.

Above: St. Augustine's Abbey. Canterbury Cathedral in the

background.

"This abbey, founded by St. Augustine in around 598, is one of the

oldest monastic sites in the country.

It was built to mark the success of the evangelical mission sent by

Pope Gregory the Great to reintroduce Christianity to the south of

England.

The Abbey was used initially as the burial place for the kings of

Kent and the early archbishops of Canterbury.

After the Norman Conquest, in the eleventh century, it became, and

took on the appearance of, a standard Benedictine Abbey.

It continued in religious use until 1538, when, like all other

monasteries in the country, it was suppressed by Henry VIII as part

of the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

After the Dissolution, part of the site was converted into a royal

palace by Henry VIII, and was used as a resting place for royal

journeys from London to the south-east ports."

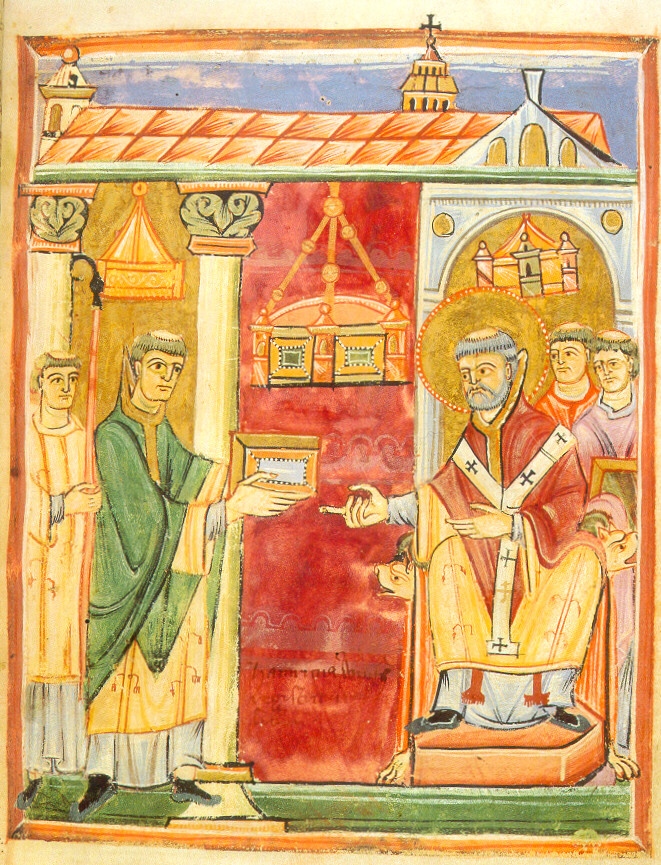

Above: Pope Gregory sending St. Augustine to England to convert

the people to Christianity, from a mid-eleventh century German

missal.

"A monastery was founded on this site in about 598 by Augustine with

a small group of monks, who had been sent from Rome by Pope Gregory

the Great to restore Christianity to southern England.

[Note: Don't confuse this St. Augustine with St. Augustine of Hippo,

the famous fifth-century theologian.]

Christianity had first been introduced to England by the Romans, but

with the collapse of the Roman Empire, and increasing invasions by

pagan peoples from northern Europe (Angles, Saxons and Jutes, soon

to be known as the English), the Christian faith survived only in

the unconquered Celtic regions of Wales and the west.

England at this time was divided into a number of separate kingdoms.

Augustine aimed to convert the royal families, hoping that the

general population would then follow their example.

Kent was chosen as the landing place for the mission, as it was the

kingdom of Ethelbert, one of the most powerful leaders of his time.

His wife, Bertha, was a Frankish princess and already a practising

Christian.

It is thought that the royal palace was located just to the east of

Canterbury in the area between the roads leading to Sandwich and

Fordwich, and that Berta and her priest Liudhard workshipped at the

church of St. Martin's.

The missionaries probably arrived in 597 and were welcomed by

Ethelbert.

They were given accommodation and the freedom to preach to his

people, although it probably wasn't until later that year that

Ethelbert himself was converted to the Christian faith.

The conversion of the King marked a turning point in the success of

the mission.

As a result Augustine was given an old Roman church in Canterbury

which was to become his cathedral, dedicated to Christ the Savior

(Christ Church), and a site to the east of the city to found a

monastery."

Above: The crypt of the central tower of Abbot Wulfric's Rotunda,

built around 1050

"Below the ruins of the medieval abbey are the remains of the

earlier Anglo-Saxon monastery established by Augustine.

They are about one metre (three feet) below the present ground

surface.

Following excavation they have largely been covered over, both for

their long-term preservation and so that the later buildings can be

more easily understood.

Only the remains of Wulfric's Rotunda and part of the Porticus of

St. Gregory have been left exposed.

The location of the main walls of the early churches has been marked

out in modern materials on the grass....

The early monastery consisted of four separate churches or chapels,

built in an east-west line across the site....

The main church was dedicted to St. Peter and St. Paul, with the

chapel of St. Mary to the east and the church of St. Pancras

detached from the rest of the buildings, further towards the eastern

boundary.

To the west of St. Peter and Paul was a further small chapel.

Though no remains have been found, it is likely that there were also

domestic quarters for the monks, probably built of timber.

Excavations below the medieval cloister revealed the remains of an

earlier formal layout which probably dates to the period of Abbot

Aelfmaer (1006-17).

"Abbot Wulfric's Rotunda... is the remains of a crypt to an

octagonal tower built by Abbot Wulfric in about 1050 to provide a

link between the church of St. Peter and Paul, and the chapel of St.

Mary.

It would have been entirely buried from sight when the Norman church

was built, and has only been uncovered by archaeological excavation.

The tower seems to have been designed as a four-storey galleried

structure with a crypt, built around a central rotunda probably open

from ground level to the roof.

Columns for the root of the central tower would have been supported

on the wedge-shaped piers that you can still see.

Abbot Wulfric was probably inspired by similar structures he had

seen in France on his visit to Rheims.

It seems likely that the tower was never completed, as Abbot Wulfric

died in 1059, and his successor Abbot Scolland then replanned the

entire church."

Above: The Norman crypt and the altar of the Chapel of St. Mary

and the Angels

"The Norman crypt was the first part of the new church to be

completed.

It was in the Romanesque style (imitating the architecture of

Ancient Rome) and was intended to be used for worship as well as for

burials.

It lies on the site of the Anglo-Saxon church of St. Mary which had

to be cleared of all its burials before work on the new church could

begin....

The lower parts of the walls are still fairly well preserved and the

ashlar stone facing blocks still have fine examples of the medieval

masons' tooling marks....

The central chapel at the east end of the church was dedicated to

The Blessed Virgin Mary in the Crypt.

It was used for the singing of mass each day until Abbot Thorne

(1272-83) decided it should be sung in the new Lady Chapel in the

nave instead, presumably so that the lay people could participate.

In 1325 the altar in this chapel was rededicated to St. Mary and the

Angels, and the alterations to the structure were possibly carried

out at this time.

The chapel was rebuilt with a square eastern end and the walls were

plastered and painted....

The northern chapel is not so well preserved, although part of the

altar can still be seen.

Abbot Wydo (1087-99) was buried here.

It was dedicated to St. Richard of Chichester during the second part

of the thirteenth century.

The crypt, although partially below ground level, was well lit with

five fifteenth-century windows on each side.

The crypt had stone vaulting supported on columns....

It is likely that these were reused from an earlier building of

Anglo-Saxon or even Roman date.

Abbot Scolland was buried in the centre of the crypt and a former

abbot, Wulfric I (who died in 1006), was reburied beside him."

Above: Tomb of St. Augustine, St. Augustine's Abbey

Above: Tomb of Wihtred, king of Kent (c. 690-725), St.

Augustine's Abbey

Above: A pigeon, one of the current inhabitants of St.

Augustine's

Abbey

Above: The remains of the Chapel of St. Pancras at the far east

end of St. Augustine's Abbey

"The Chapel of St. Pancras... was the easternmost of the line of

churches built during the Anglo-Saxon period, and is the only one of

which substantial remains can still be seen.

It has survived because its position did not interfere with the

Norman rebuilding of the abbey church.

It continued in use as a cemetery chapel, and contains a number of

burials.

The Anglo-Saxon parts of the building can be distinguished from the

phases of later rebuilding by the exclusive use of reused Roman

brick.

This is similar to the technique of building found in the buried

remains of the church of Saints Peter and Paul.

It is likely to have been built during the seventh century, although

in the fourteenth century the monks believed that this was an

earlier pagan building which had been consecrated and used by St.

Augustine.

It was believed that Augustine had said his first mass in Canterbury

in the area of the southern chapel.

The original building consisted of a nave with an apsidal chancel at

the east end, and small single chapels on the north and south sides.

The nave was divided from the chancel by a screen supported on four

columns....

The altar would have been situated at the east end.

The building seems to have been rebuilt during the middle years of

the eighth century, largely to the same plan, but with the addition

of a porch at the west end.

In 1361 the chancel of the chapel was damaged in a storm, and was

rebuilt with a square east end.

The window which now dominates this end of the building was probably

inserted into the wall in about 1390.

In 1494 it was recorded that a hermit lived here."

Above: Chaucer is everywhere!

Back to Rochester

Advance to Reculver

Return to places page

Return to home page

|