|

Monday, February 21, 2005

Planning for A New Chief:

Tuesday's New York Times has a notable article on the Administration's plans for the replacement of Chief Justice Rehnquist: [F]or senior White House officials, as well as a handful of others who follow the court closely, a working assumption about what is going to happen has already taken shape. The strong expectation, senior administration officials and others said, is that Chief Justice Rehnquist is making his best effort to serve out the remainder of the term that ends in June before resigning. And the only question, they say, is whether the 80-year-old chief justice, who is suffering from thyroid cancer and the effects of his treatment, will be able to do so.

The people who said that this was the assumption in the White House included senior administration officials, senior Congressional officials and people who have been consulted by senior White House officials.

Top White House officials have discussed the situation, one of those people said, and have concluded that they will have to be ready for President Bush to make known his intentions for replacing the chief justice no later than June but possibly sooner. They have prepared ever-narrowing lists of candidates to be nominated for the court, one official said.

. . . .

. . . [I]t is improbable that the expectations about Chief Justice Rehnquist stem from any direct signal from him. Rather, it is the combination of several factors, including his age and illness and his statement years ago that he well understood the tradition in which justices try to leave when the White House is occupied by a president of the same party as the one who nominated that justice. According to the Times, the four key names on the Administration's short list are: 1) Michael W. McConnell of the United States Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, 2) John G. Roberts of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, 3) J. Harvie Wilkinson III of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, and 4) J. Michael Luttig of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. Mentioned as "[a]nother possible candidate" is Samuel A. Alito of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. The notable part about this short list is that the candidates are the intellectual heavy hitters culled from previous lists. All four of the candidates on the primary list are themselves former Supreme Court clerks, and they are widely considered to be some of the brightest stars in the federal judiciary. Alito has stellar credentials and is right there with them, too. There isn't a dud in the group. Which judge the President will select for the Court likely depends on what kind of Chief Justice the President wants to see. Wilkinson probably would be the most like Rehnquist: a reliable conservative but with strong tactical instincts. Luttig has the harder ideological edge, which is an asset if there are more openings for Bush to fill but a potential liability if he needs to keep Kennedy and O'Connor on board. Both Roberts and McConnell are brilliant, articulate and could be intellectual leaders on the Court for a generaton, but both are also fairly new and relatively untested as lower court judges. Alito would be a reliable conservative and could excel at building consensus across the ideological spectrum. At this point, my own preference is John Roberts first and Michael McConnell second. I think Roberts and McConnell are the two judges on the short list with the strongest potential to be "great" Chief Justices. I have a preference for Roberts not only because he is considered one of the best (if not the best) Supreme Court lawyers of his generation, but because his opinions as a D.C. Circuit judge have been simply outstanding. I've read about a half dozen Roberts opinions in the last year, and they were all models for what an appellate opinion should be. Tight, focused, scholarly, and balanced. They were beautifully written, too; the guy can make even FERC disputes seem interesting. I also saw a dash of Robert Jackson in them — a sort of perspective that reflects a deep understanding of how this case fits into other ones. Finally, Roberts pulls it off without being flashy. His opinions are highly readable but don't beg for more attention. Excellent stuff.

Will Blogs Kill the Law Review Case Comment?

While mulling over my blog post below about a recent court decision, it occured to me that one way blogs will change the content of law reviews is by rendering case comments superfluous. A case comment is a brief student-written article, usually around 10 pages long, explaining and offering commentary on a recent court decision. Case comments traditionally have served three functions: 1) Alerting readers to a recent decision, 2) Offering a scholarly assessment of the decision soon after the decision is out, hopefully before academics and appeals courts have had time to digest it, and 3) Helping editors improve their writing skills and generating a writing sample for future job applications. The question is, will blogs drive case comments out of business? My sense is that blogs have eclipsed the first two functions of case comments. How Appealing alerts readers to new court decisions, often on the same day they are published (at least when Howard doesn't have the nerve to go on vacation). Within a matters of days, the blogosphere usually generates a discussion among practitioners, law professors, students, and interested laypersons about the merits of notable decisions. In general, the quality of legal analysis generated by the blawgs is notably higher than that of case comments; practitioners and law professors have more expertise and experience than 2Ls, and the back-and-forth debate online generally tightens loose thinking pretty quickly. In contrast, student case comments are usually short on perspective and long on political agendas; the majority seem to fall into the "I'm liberal and want to bash the Rehnquist Court" mold, or the "I'm conservative and this Reinhardt decision is nuts" mold. By the time case comments come out, usually about a year after the decision, it is too little, too late. Litigants, judicial clerks, and anyone else involved in the case can read the output of the blawgs online and take away whatever lessons they wish from the commentary; few are going to go hunting through westlaw for student comments a year or two later. For example, if Eugene blogs about a First Amendment decision the day it comes out, offering his assessment of the case and pointing out its strengths and weaknesses, will anyone care if a year later the Brown Journal of Law and Identity publishes a case comment by a 2L editor explaining that he liked or didn't like the decision? In a pre-blawg world, such a case comment might be the very first piece of analysis on the case; it could be important because there is nothing else on the opinion. The role of first responder is now played by the blogosphere. Perhaps the third function of case comments is enough to keep case comments alive, at least for a decade or two. But my prediction is that journals will eventually stop publishing case comments and instead focus more on scholarship surveys (where student reviews could be very helpful) and broader note topics. Thoughts? Reactions? I have enabled comments.

Unusual Fourth Amendment "Consent" Case:

Imagine you get lost driving in McLean, Virginia, late one night, and that you find yourself near the CIA headquarters. You decide to drive up the headquarters main gate so you can ask for directions. Moments after you ask for directions, two armed security officers come out and yell at you to put your hands up. One officer has a nine-millimeter pistol; the other has a shotgun positioned so it could be readily fired at you. You put your hands up, and the officers start asking you questions. Do you know where you are? Are there any drugs or alcohol in the vehicle? Do you have any ID? On the night of October 14, 2002, this happened to Terrence Smith. The CIA security officers quickly found out that Smith was driving without a license, and ordered him out of the car. The officers concluded that Smith appeared to have been drinking, and eventually arrested him for drunk driving (a charge that he was acquitted of at trial). During a search incident to his arrest for DWI, the officers found cocaine in Smith's car. Smith moved to suppress the cocaine on the ground that he had been unreasonably seized when the officers came out with their guns and ordered him to put his hands up. Judge Gerald Lee of the EDVA denied the motion to suppress, ruling that Smith had been seized but that the police had reasonable suspicion to seize him under the principles of Terry v. Ohio. Smith was convicted of the cocaine charges in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia and sentenced by Judge Lee to two years and two days in prison. Smith then filed an appeal renewing his argument that the chared against him resulted from an unreasonable seizure. In an opinion by Judge Luttig published on January 27th, the Fourth Circuit affirmed the conviction. This much is unremarkable; while Smith was obviously seized during the encounter, it seems the evidence against him was obtained in ways unrelated to seizure. The evidence was not a fruit of the seizure, and the seizure itself likely was reasonable given the heightened security concerns at the CIA headquarters. As a result, the conviction should have been affirmed. But Judge Luttig didn't affirm on these grounds. Instead, he resolved the case on a rationale that strikes me as rather remarkable. According to Judge Luttig, the encounter at the CIA headquarters gate was actually consensual — or at least reasonably was believed by the officers to be consenusal. That's right, Smith actually wanted to have his liberty restricted, at least according to the court: We are satisfied that Smith's unauthorized and voluntary approach to officers outside the CIA headquarters in the middle of the night justified a belief by the officers that he was consenting to the customary security precautions required at that time of the night at the entrance to such a protected facility, regardless of whether Smith intended to consent to a demand for identification by armed officers or whether he even knew that he was so consenting. A reasonable person would certainly know that officers at the CIA gate would be armed when approaching an unidentified car, and that such officers would seek to determine who was entering the property without authorization. As such, a reasonable person would view a decision to initiate a consensual encounter with officers near the gate of the CIA as consent to these foreseeable circumstances. The officers were thus plainly justified in believing that their encounter with Smith at the Jersey barrier was consensual. Therefore, if any seizure occurred, it was within the scope of Smith's consent and thus reasonable within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. This strikes me as quite far-fetched. The Supreme Court's test for determining the scope of consent is what a reasonable person listening to the exchange between the officer and the suspect would think the suspect was agreeing to let the officer do. See Florida v. Jimeno, 500 U.S. 248, 251 (1991). It's hard to imagine that asking for directions is a form of request to have armed officers order you to put your hands up and detain you. The guy wanted to get directions; he didn't expect the Spanish Inquisition (of course, nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!). Whether the suspect should have known that something like this might eventually happen isn't the test; forseeability is not the same as consent. The opinion tries to work around this difficulty by using Illinois v. Rodriguez, 497 U.S. 177 (1990), to modify the Jimeno test so that it focuses more on the perspective and mindset of the police officer. I don't think that works, though. In Rodriguez, the Supreme Court held that "determination of [authority to] consent to enter [a home to conduct a search] must be judged against an objective standard: would the facts available to the officer at the moment warrant a man of reasonable caution in the belief that the consenting party had authority over the premises?" The idea is that if a person reasonably seems to have the authority to consent to a search or seizure, the resulting search or seizure is not invalid if it turns out later that the person was just posing as someone with that authority. In the paragraph before the one excerpted above, Judge Luttig gives Rodriguez a "cf." cite for the view that the key question is only whether the officer's subjective belief about the consent was reasonable from his perspective. But Rodriguez is not so broad; it deals only with authority to consent (something that is not an issue here), not how to construe the scope of consent. More broadly, I don't think I have ever seen a case in which a court found a consensual seizure of a person. I might decide to let the police have my stuff, and in that case I am consenting to have the police take away my property. The seizure of my stuff is consensual, and therefore reasonable. But seizures of persons are distinct from seizures of property under the Fourth Amendment; the test is no longer deprivation of a possessory interest, but rather whether a reasonable person in that situation would feel free to leave. I suppose it's theoretically possible to voluntarily consent to have your freedom to leave revoked, but it seems like an odd (and dangerous) rationale. Under existing precedents, judicial scrutiny of government security practices generally invites the courts to balance the need for the practice with its intrusiveness. If a government search or seizure is deemed "consensual" when a person really should have known it was coming, however, then such procedures generally will be exempt from judicial scrutiny. Thanks to CrimLaw for the heads-up on this case; CrimLaw's coverage also offers some extensive analysis.

Everyday life in Israel:

As something of an antidote to the political and military images of we see every day on t.v., I though I'd pass along this picture my sister-in-law sent me of my niece and nephew (on the left) and their two friends.

Tear Down This Wall:

As Scott Johnson notes this morning, the speech restrictions regarding the Dartmouth Trustee Elections are very strict. Which makes it all that more crucial that they be enforced in an even-handed manner.

Herewith the text of the email I sent to the Affairs Office and Alumni Council Ballot Committee this morning regarding the incident described in an earlier post:

I was surprised and disappointed to see the announcement in the "Speaking of Dartmouth" Electronic Newsletter last week that promoted the candidacies of the four official alumni candidates. Given that candidacy deadline does not close until this Wednesday Feb. 23, I believe that this announcement was premature, inappropriate, and very detrimental to the prospects of a fair election for the Dartmouth Board of Trustess. First, by referring to "the candidates" in the email announcement, this implies that the 4 candidates listed there will be the full slate of candidates. Second, this is very detrimental to my efforts in that any alumni who clicked through that link last week will be much less likely to do so with respect to any future announcements. Third, any future announcement regarding an updated slate of candidates will not only mention my candidacy but will inevitably also again promote the Alumni Council candidates; thus, this puts me at a permanent disadvatage.

To the extent that the College and Alumni Council insist on strict rules on communication with alumni during the election process, it is imperative that these rules be applied in an even-handed manner to all qualified candidates and that there is neither the appearance nor the acutal effect of favoring some candidates over another.

I believe that the announcement at this time was premature and fundamentally unfair to independent candidates and should have not been issued until the deadline for candidates was closed on Feb. 23.

As a result, I request that the College and the Alumni Council take the following steps to attempt to redress this situation:

First, I request the IMMEDIATE REMOVAL of the video by Karen McKeel Calby '81 endorsing the official Alumni Council nominees. This is a completely inappropriate advantage for the official candidates and there is simply no possible way for a qualified petition candidate to offset this advantage.

Second, I would like to request that the following to try rectify this unfair communication on behalf of the Alumni Council candidates. First, I would like express authorization to maintain my personal website for the duration of the balloting period, to provide alumni with an equal opportunity to discover and learn about my candidacy. Second, after I am qualified as an official candidate this week I would like a special email to be sent to all subscribers of "Speaking of Darmouth" that mentions my addition to the ballot and directs interested alumni to my personal website. I would request that this communication mention specifically that the prior email communication was premature and prior to the candidate deadline, and that the email that mentions my candidacy is being sent to provide all candidates with an equal playing field. It is important that this email mention only myself and any other petition candidates who qualify for the ballot, and does not exacerbate the

situation by again directing alumni to the official Alumni website.

I believe this is a serious breach of the promise of a fair and open Trustee Election. If the College is going to impose speech restraints on Trustee candidates, it is imperative that those rules be applied in an even-handed manner and do not favor some candidates at the expense of others.

Update:

Comments by Dartmouth Students Joe Malchow and Nathaniel Ward.

Related Posts (on one page): - Tear Down This Wall:

- Dartmouth Undying:

Quinnipiac Talk Cancelled:

A severe snowstorm that has already begun, combined with freezing rain later this afternoon, will prevent me from driving to New Haven from Boston this morning, so my talk today at Quinnipiac has been cancelled. (The school itself is closed until 11.) I have offered to reschedule for late April, and will post here if that date works out for them. My apologies to anyone who was planning to attend, but I already have several inches of snow on my driveway and it is falling pretty fast.

Later this week, I will be at Cumberland Law School in Birmingham, Alabama on Thursday at noon in Room 116 (the Trial Courtroom) (2/24) and University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa on Friday at noon (2/25).

On Thursday of next week (3/03) I will be at NYU at noon and Columbia at 6:30 in Greene Hall 104.

Update: I now know the location of my talk at Cumberland (see above).

Dartmouth Undying:

A count of my Trustee Elections petitions indicates that I have gained more than the 500 petitions (signed in non-black ink, of course) needed to qualify for the ballot for the Dartmouth Board of Trustee elections. My petitions will be delivered to the College today. A special thanks to all the Dartmouth Alumni who have taken the time to sign and return petitions.

The outpouring of support that I have received in this effort has been a truly gratifying experience. I have received signed petitions from alumni all across the range of classes--I believe that Class of '33 is the earliest vintage of alumni who have returned a petition. I have been especially struck by the enthusiasm from recent alumni, from the past 5 years or so, which I believe attests to the frustration level of current Dartmouth students and parents.

This has also been a deeply humbling experience. One alum apologized for his handwriting, noting that he is almost completely blind, yet wanted to return a petition. The handwriting on a petition from the Class of '38 was shaky, but back it came. Many alumni took the time to include long, thoughtful letters expressing their views on what is right and wrong about Dartmouth--I read all of those letters and found many of them to be both moving and insightful. Many others included short notes, from "Go Get 'Em" to "Bring Back Beta!".

This experience has reminded me what a deep sense of trust and obligation comes with being a member of the Dartmouth Board of Trustees. The depth of loyalty and passion that Dartmouth alumni feel toward the College is fundamentally different from any other College in America. Can you imagine any other college or university in America where alumni would take the time to read a letter and sign a petition--for a perfect stranger--to be able to run for the Board of Trustees? And then taking the time to compose a note or letter to express their own thoughts about what can be done to improve Dartmouth?

Dartmouth is a special place, and serving on the Board is a sacred trust for the generations of alumni who have built and maintained that legacy. The Dartmouth experience has brought together students of many different backgrounds across the centuries and left its indelible stamp on each of them, and they have left their mark on the College. It pains me when Dartmouth's leadership turns its back on this legacy. If I am elected to the Board, I will work to improve Dartmouth and to pass this legacy on to future generations of Dartmouth alumni.

I am grateful for the support of the alumni who have signed petitions, and I hope that you, and your friends, will vote for me when the balloting begins next month.

As for me, Dartmouth's dislike of free speech applies not only to students, but apparently to alumni as well. Once I qualify as a candidate, I will come under the maddeningly vague rules governing campaigning (described in Scott Johnson's article today in the Weekly Standard On-Line). I am still not clear on what this means with respect to my communications with alumni. It may require me to take down my Dartmouth Trustee Election website, however, so I would encourage those who are interested to visit my website while you still have the opportunity. You will find not only do I have information about my goals for Dartmouth, but I have links to many Dartmouth articles of interest.

Of course, as with students as well, it appears that the College does not apply its restrictions on free speech in an even-handed manner. I notified the College last week that I had garnered sufficient signatures to qualify for the ballot. Nonetheless, at the end of last week--after I notified them, and less than one week before the close of the deadline for candidates to qualify (Feb. 23)--the College sent out its electronic newsletter "Speaking of Dartmouth", which contained an advertisement for alumni to follow a link to "meet" the four candidates named by the Alumni Council.

Although petty, this little episode seems all too typical of the College's uneven attitude toward free speech on campus and efforts to manipulate the information provided to alumni. This is one of the reasons that my goals for Dartmouth include restoring the rights of free speech on campus and increasing the openness and transparency of College governance.

I have asked for an explanation from alumni affairs about this premature communication and will request equal time from the College, but of course, this is a uniquely detrimental and one-sided communication to an independent candidate like myself, in that any future announcements that include me will direct alumni to a website that will include all of the qualified candidates. Many of those who clicked through last week will have little interest in clicking through to the alumni candidate web page again. Would it have killed them to just hold off one more week to see if any other candidates qualified for the ballot before they sent their communication?

For alumni who may be interested in expressing your views on this or other matters of import regarding the election, the email address for Dartmouth Alumni Relations is alumni.relations@dartmouth.edu

Thank you again Dartmouth Alumni and please remember to vote beginning next month!!

Update:

Dartmouth undergraduate blogger Joe Malchow comments here. Related Posts (on one page): - Tear Down This Wall:

- Dartmouth Undying:

Weekly Standard on Dartmouth Trustee Election:

Scott Johnson of Powerline (and a Dartmouth alum, as it turns out) has an interesting commentary today, "Bucking the Deans at Dartmouth" in the Weekly Standard On-Line profiling the Dartmouth Trustee Election and putting it in larger historical context.

Sunday, February 20, 2005

A CLOSER LOOK AT TERM LIMITS; PROBLEMS WITH THE CARRINGTON/CRAMTON PROPOSAL.�

Randy Barnett raises the issue of term limits, which I blogged about a few weeks ago. There are at least three major questions to be answered in deciding whether to endorse the Carrington/Cramton proposal, or any specific proposal on term limits for the Supreme Court:

1. Do you favor 18-year term limits for Supreme Court justices?

Such proposals date back over a decade to (as I recall) at least Greg Easterbrook's. The Carrington/Cramton proposal from late 2004 and the one that I discussed on CONLAWPROF about 4-5 years ago and the one that Steve Calabresi and Akhil Amar proposed in a 2002 Washington Post op-ed all opt for 18-year term limits.

2. Can this be accomplished by statute by retaining life tenure (with reduced powers and responsibilities) or must such a change be accomplished by a Constitutional Amendment?

Reasonable people can differ on this. The Carrington/Cramton proposal opts for a statute. Early versions of the Calabresi proposal said that either a statute or a Constitutional amendment were possible. The draft that Calabresi and I are rewriting now calls for Constitutional amendment, not a statute, as the wiser course, which was my initial cut when Calabresi first raised the idea of Supreme Court term limits with me back in 2000.

3. Which proposal do you favor?

Even if you are willing to endorse 18-year term limits and think it can be done by statute, rather than by constitutional amendment, there is still the question of which implementation of 18-year term limits works best. I know that Calabresi, when he endorsed the Carrington/Cramton proposal thought that it did much the same thing as the proposal that he and I have been working on for years. But it doesn't. (Obviously, between the two, he favors our proposal.) The Carrington/Cramton proposal might still be better than the status quo (I don't know), but I think the version that Steve Calabresi and I developed is better on specifics—which of course one would expect us to think of our own proposal.

I just read the Carrington/Cramton proposal for the first time last night, and I think there are some serious problems with it. I will leave aside for now some problems with their phase-in period (because any proposal will have some potential oddities associated with the phase-in period), and I will focus only on problems with the Carrington/Cramton proposal once it is fully phased in and functioning.

The Carrington/Cramton proposal provides BOTH that "the nine who are junior in commission shall sit regularly on the Court" hearing cases AND that "One Justice or Chief Justice, and only one, shall be appointed during each [2-year] term of Congress." While under the current law and any scheme that I have considered, the Senate always has the power to delay approving and thereby to delay adding a justice for strategic reasons, under current law and our proposal, the President and the Senate have no power to REMOVE a justice from hearing cases because they want to replace him or her. But under the Carrington/Cramton proposal, they do. And this dispute would happen, not just occasionally, but with almost every appointment.

Imagine if the Carrington/Cramton proposal were fully phased in today and a Democratic appointee and strong liberal were the most senior sitting justice. The Carrington/Cramton proposal provides that "One Justice or Chief Justice, and only one, shall be appointed during each [2-year] term of Congress." Accordingly, some in the Bush White House would want the new Bush choice confirmed NOW in the first months of the new Congress, so the new justice could bump a sitting Democratic justice off the cases already being heard. The Democrats would respond, "What's your hurry?" Under the Carrington/Cramton bill, they could wait until late in 2006 to replace the current sitting justice. Suppose that there is a major case coming before the Court late in this term and the more political branches want the senior Justice bumped off the Court that would hear the case. This would seem to me to be highly disadvantageous.

Further, this power to remove sitting justices from hearing cases (including from anticipated specific cases) at the discretion of the other two branches would raise Separation of Powers concerns. Indeed, giving the two non-judicial branches the discretion to set the end of a particular justice's ability to hear cases routinely would make it particularly inappropriate to try to do so by statute, rather than Constitutional amendment. I don't think that the Carrington/Cramton proposal can both urge a statutory solution and give the executive and legislative branches the discretion over when during a 2-year window to remove a sitting justice from hearing cases.

Further, suppose that the Bush White House gets its choice through in February or March in the first year of the new Congress. The new justice would obviously supplant the senior justice on cases on which certiorari had not yet been granted, but what about cases on which cert. had been granted, but the cases not yet argued? What about cases argued but not yet decided? As I read the C/C proposal, the new justice would sit immediately, probably bumping the senior justice off cases heard but not decided: "The nine who are junior in commission shall sit regularly on the Court." At the least, the application of their statute to existing cases is unclear.

I apologize for not making our full specific proposal public now, but (while its logic has been worked out and we have a draft provision) we have not yet run it by those more skilled in legislative drafting. We go for fixed terms of 18 years, each starting and ending in the summers of odd years:

c. The Length of the Terms of Regular Service. There shall be nine staggered full terms of Regular Service on the Supreme Court, each approximately 18 years in length, with terms beginning and ending every two years in odd numbered years. An old term of Regular Service shall end and a new term shall begin on July 1 of each odd numbered year if the Supreme Court has recessed for the summer by that date. Otherwise, the term of Regular Service shall begin and end on the first full day of recess after July 1, but in no event shall the date for beginning and ending a term of Regular Service be later than October 1 of the relevant odd-numbered year.

Calabresi and I expect to make our draft, which has been circulating in a limited form since 2001 or 2002, finally public in mid-March. At that time, I will try to set out what I think are the chief merits and demerits of our Constitutional proposal.

For the reason I set out above, while I strongly favor the idea of 18-year term limits, I do not favor the particular proposal put forward Carrington and Cramton, though with revisions to track more closely our proposal, I would probably favor it.

Summers controversy and conservatives in academia:

A commentator at Janegalt.net:

Correct me if I'm wrong, but about 6-8 weeks ago there was a flurry of activity in the blogosphere re: the dearth of conservatives/Republicans on university faculties. If I recall, the general, not to mention immediate, consensus among liberal/Democrat professors was that Republicans either didn't have the intellectual oomph to be professors, or just preferred to do other things. Natural selection, in other words, certainly not any sort of bias. We now have Harvard jumping through hoops to explain the dearth of female professors in math and science departments. They're not quite sure why this condition endures, except for the fact that it absolutely, positively, ain't natural selection. Strangely enough, this was another immediate, reflexive consensus, excepting Mr. Summers' brief but embarrassing romp off of the intellectual plantation.

I would add that if Summers' quite measured comments have gotten him into such hot water, imagine how regular faculty, untenured faculty, graduate students, and undergraduates whose views don't reflect the politically correct mainstream are treated, and how much their careers can be placed in potential jeopardy. And then consider whether a young conservative or libertarian scholar would be wise in pursuing an academic career.

As for the argument that many scholarly issues in academia are non-political, ahd thus not subject to ideological prejudice, consider another Janegalt commentator's missive:

I'm a newly hired scientist at Harvard, and I have been amazed by the fact that almost all of my colleagues agree that this hypothesis (that biological differences contribute to the persistent discrepancy between the numbers of men and women in the natural sciences and mathematics) should not even be considered.

If science can't be objective and free from political correctness, what can?

Saturday, February 19, 2005

Secret Tapes of George W. Bush:

An interesting piece in today's New York Times.

Horse and Buggies Versus Cars:

Is it possible to write a lengthy article on the safety and other risks posed to consumers by early automobiles, have it reviewed by prominent legal historians, and published in a prestigious legal history journal, without ever considering the issue as to whether cars were more or less safe than the horse and buggies they substituted for? (Aside: one of my great-grandfathers was killed in a horse and buggy accident.) Even if one of the primary cases you focus on involved a defective wheel, an issue that no doubt arose with regard to buggies/carriages as well?

Not only is it possible, it's been done. The same article manages not to ignore the abundant law and economics scholarship on consumer warranties, but rather to only cite the few L & E scholarship (Logue, Hanson, Croley) who are sympathetic to enterprise liability. Friedrich Kessler, of contracts of adhesion fame, is cited often, but George Priest (among others who have harshly criticized Kessler) is cited not once. As someone who does a lot of work in legal history, this sort of thing frustrates me quite a lot.

Friday, February 18, 2005

When Barry Lynn Speaks, Tony Mauro Listens:

Tony Mauro has a new article in Legal Times that begins: Justice Thomas Finds Himself in Inauguration Controversy

Tony Mauro

Legal Times

02-17-2005

A week before Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist swore in President George W. Bush to a second term as president last month, Justice Clarence Thomas presided over a little-noticed inauguration inside the Court building that has generated some controversy.

In an invitation-only ceremony, Thomas on Jan. 13 gave the oath of office to newly elected Alabama Supreme Court Justice Tom Parker. . . . According to the article, the private swearing in of Justice Parker generated "some controversy" because Justice Paker is a protege of Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore, the so-called "Ten Commandments judge," who defied the federal courts by refusing to comply with judicial orders to remove the Ten Commandments from the courthouse that hosts the Alabama Supreme Court. The controversial part about swearing in Parker, according to Mauro, is that the Supreme Court will be deciding cases this Term on the constitutionality of Ten Commandment displays. The article suggests that offering symbolic support to someone who is a close friend of someone closely associated with the public debate over issues relating to a pending case is problematic, even if the support was private. This seemed like a pretty tenuous connection to me, so I re-read the article to find out who the people are that find this controversial. As best I can tell, the article's only source for that view is a single man: Barry Lynn, the executive director of Americans United for Separation of Church and State. I think it's fair to describe Lynn as a harsh and regular critic of Justice Thomas. Come to think of it, I don't think I've ever seen Lynn make a comment about Justice Thomas that wasn't harshly critical. Maybe it has happened, but if it has it would be, well, pretty newsworthy. Here's my question: Is the fact that Barry Lynn objects to something Justice Thomas did itself worthy of a news story? Perhaps lots of people see the fact that Justice Thomas would swear in a protege of Roy Moore as controversial, and Mauro just chose Lynn to quote as representative of that view. Perhaps there is something else to this story that was cut out during the editing process. But the story as written seems to be about Barry Lynn's objections, and only his objections. Maybe I'm missing something, but this story seems to be less about reporting on a controversy than trying to create one. UDPATE: While it doesn't have anything to do with Lynn's rationale for criticizing Thomas, this important post over at Southern Appeal is more than enough to convince me that that Parker is someone Justice Thomas shouldn't be supporting. Oddly, it may be that swearing in Parker should be controversial — just not for the reasons Mauro mentions in his article.

Term Limiting Supreme Court Justices:

Lately I was asked to endorse the following proposal by law professors Paul D. Carrington and Roger C. Cramton to limit the terms of Supreme Court Justices:

THE SUPREME COURT RENEWAL ACT OF 2005

Congress should enact the following as section 1 of Title 28 of the United States Code:

(a) The Supreme Court shall be a Court of nine Justices, one of whom shall be appointed as Chief Justice, and any six of whom shall constitute a quorum.

(b) One Justice or Chief Justice, and only one, shall be appointed during each term of Congress, unless during that term an appointment is required by Subsection (c). If an appointment under this Subsection results in the availability of more than nine Justices, the nine who are junior in commission shall sit regularly on the Court. Justices who are not among the nine junior in commission shall become Senior Justices who shall participate in the Court's authority to adopt procedural rules and perform judicial duties in their respective circuits or as otherwise designated by the Chief Justice.

(c) If a vacancy occurs among the nine sitting Justices, the Chief Justice shall fill any temporary vacancy by recalling Senior Justices in reverse order of seniority. If no Senior Justice is available, a new Justice or Chief Justice shall be appointed and considered as the Justice required to be appointed during that term of Congress. If more than one such vacancy arises, any additional appointment will be considered as the Justice required to be appointed during the next term of Congress for which no appointment has yet been made.

(d) If recusal or temporary disability prevents a sitting Justice from participating in a case being heard on the merits, the Chief Justice shall recall Senior Justices in reverse order of seniority to provide a nine-member Court in any such case.

(e) Justices sitting on the Court at the time of this enactment shall be permitted to sit regularly on the Court until their retirement, death, removal or voluntary acceptance of status as a Senior Justice. As explain by its authors, this proposal would have the effect of limiting the term of "active" justices to approximately 18 years:

The result is that all Justices appointed to the Court in the future would serve as the nine deliberating and deciding members for a period of about eighteen years (depending upon the interval between the initial appointment and the promptness of the appointment process eighteen years later). However, the Act does not restrict the lifetime tenure of the Article III judges appointed as a Justice or Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Instead, it defines the regular membership of the Court as consisting of the nine most recently appointed Justices. Some of the Senior Justices who no longer participate regularly in the Court's decisional work may be called upon to provide a nine-member Court when that is necessary (see Subsection (d)). And all of them continue to retain the title of "Justice of the Supreme Court" and to exercise the judicial power of the United States as judges of a circuit court, a district court, or some other Article III court. In short, the Act defines the "office" of a Supreme Court "judge" in a new way. This feature distinguishes the Act from statutory proposals to place age limits or fixed terms of service on Supreme Court Justices. Senior Justices will continue to have lifetime tenure as Article III judges in accordance with the "good behavior" clause of Section 3 of Article III. This proposal has already been endorsed by law professors representing a wide political spectrum. They include: Vickram D. Amar, Jack M. Balkin, Steven G. Calabresi, Walter E. Dellinger III, Richard A. Epstein, John H. Garvey, Lino A. Graglia, Michael Heise, Yale Kamisar, and Sanford Levinson.

I tend to favor term limits--what the Founders called "rotation in office"--for elected officials, but this proposal gave me pause. I am not as unhappy with the current system of judicial appointments as some on the left and right. Still, this proposal seems to have some merits in that it regularizes the process of adding new members to the court. (I cannot find the actual proposal on line so you can read the justifications offered by its authors, but you can read a New York Times story on the proposal here. If someone finds a link to the full proposal, I will add it here.)

So far, I have not signed on, but was curious to hear thoughtful reader reaction. So I have activated comments. I am particularly interested in hearing potential problems with the proposal, as its purported benefits are more obvious. However, feel free to voice your support as well as opposition. But reasons will be more persuasive to me than expressed preferences.

Update: On comments, Crime and Federalism Blog notes this online Legal Affairs Debate last week between Norman Ornstein of AEI and my BU colleague Ward Farnsworth. Readers may want to read it before adding their 2 cents.

Summers Transcript Released:

Harvard has released a transcript of the remarks by President Lawrence Summers that has gotten him into such hot water. You can access them here.

Journal Name Change:

This may be just a coincidence, but only a few weeks after Harvard President Lawrence Summers' controversial remarks on possible innate differences between men and women, the Harvard Women's Law Journal has decided to change its name to the Harvard Journal of Law & Gender. In a letter to the editor of the Harvard Law Record, the editors-in-chief of the Journal explain that the name change "indicates our unwillingness to rely upon essentialist arguments based on biological sex," among other things. Of course, if this change was in fact triggered by Summers' speech, it pales in comparison to other fallout from the speech.

IMAO Group-Blogging:

IMAO, formerly Frank J.'s private preserve, has become a group blog (announcement here). The e-mail informed me that, "IMAO will surely now storm to the top of the blogosphere, leaving many bodies in its wake. Pity IMAO's enemies."

Also, the e-mail included a note: "Your link to IMAO has the site's name spelled wrong (it's 'IMAO' not 'Scrappleface'). Also, the URL is all wrong."

New Mexico Lesbian Devil Sex Case:

I blogged about this prosecution earlier this week; my view was that the accused simply wasn't guilty of a crime under New Mexico law, at least under that portion of New Mexico law -- distribution to minors or display to minors of obscene-as-to-minors materials -- that was being discussed.

Ruth Waytz, the wife of the artist who drew the allegedly obscene-as-to-minors sticker, now reports:

Dean Young's case was dismissed this morning, but the judge did so Without Prejudice, which means the NM authorities are still free to file other

charges against him in the future. Not sure what those other charges might be . . . .

Maybe Young did something else that actually was a crime, but my sense is that he's off the hook for the sticker. Related Posts (on one page): - New Mexico Lesbian Devil Sex Case:

- New Mexico Sticker Case:

"History Doesn't Repeat Itself, But It Rhymes":

A while back, I got several messages from readers attributing this quote to Mark Twain. I'm always skeptical of such attributions, since Twain -- plus a few other people, such as Winston Churchill, Dorothy Parker, George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, Ambrose Bierce, Benjamin Disraeli, and H.L. Mencken -- seem to be magnets for loose quotations. If you're not sure of the source, credit Twain, and that'll be plausible enough. So I asked the indispensable UCLA Law School research library to track it down. (Yes, I can legitimately do that, since I plan on using the quote in my law review article.)

Here's what seems to be the scoop, courtesy of Jenny Lentz: The quote has indeed been often attributed to Mark Twain, but there doesn't seem to be much proof that he indeed said it. The most detailed source she could find was this note in an article by Lawrence P. Wilkins in 28 Indiana Law Review 135 (1995):

[The quote was a]ttributed [to mark Twain] by Allen D. Boyer in Activist Shareholders, Corporate Directors, and Institutional Investment: Some Lessons from the Robber Barons, 50 WASH. & LEE L. REV. 977, 977 (1993), who saw the attribution in ROBERT SOBEL, PANIC ON WALL STREET 431 (1988). Professor Sobel saw the attribution some time ago in an editorial column in the New York Times, the author of which he cannot recall. He has consulted with several Twain scholars across the country, and all agree that the quotation sounds very much like something Twain would say, but none seems able to find the actual words in Twain's papers. Telephone conversations with Allen D. Boyer and Robert Sobel, March 3, 1995 and March 7, 1995. It is somewhat ironic that this quotation cannot be definitively traced to Twain, whose energies were spent in great measure to protect his rights of authorship. . . .

In any case, I can still easily use the quote, just giving it as "Attributed to Mark Twain." But it's worth noting that there's some uncertainty about it. If anyone can resolve this uncertainty by a specific pointer to a written work by Twain -- and not just by a pointer to someone who has attributed the quote to Twain -- please let me know.

Talk About No Respect...

This from the the Manhattan Jaspers basketball website:

Manhattan gets back in action on Saturday, February 19, when the Jaspers travel to Fairfax, VA to take on George Washington in the team's final non-conference game. Tip-off is slated for 4:00 p.m.

GMU beat 23-3 Old Dominion, earns an ESPN Bracket Buster game this weekend, and the team they are playing still can't get the name right. It is George Mason, not George Washington, and not Georgetown! Its bad enough being the other "George" school around here, but sometimes it gets old being the other, other "George" school in these parts.

Thursday, February 17, 2005

Yet Another Ridiculous Lawsuit:

Ted Frank (OverLawyered) reports:

Michael J. Zwebner, the CEO of penny-stock holding company Universal Communication Systems, is unhappy that he's being flamed on the RagingBull.com message board, run by Lycos. He may have a legitimate beef to some extent. . . .

[But] Zwebner's litigation methods . . .are questionable. He's filed five lawsuits in federal court in Miami, against anonymous posters, against Lycos (for, among other things, "trademark violations" for naming a message board after the ticker symbol UCSY), and even a couple of purported class actions. He's especially upset at one anonymous poster, who has the especially credible username of Wolfblitzzer0 [sic].

So, Zwebner has sued . . . CNN and the real-life Wolf Blitzer! It seems, according to Zwebner's view of the world, that Blitzer is supposed to be on the lookout for anonymous posters using similar names, and should be held liable for such posters' postings when he fails to police the use of such usernames. . . .

Appalling. First, I doubt that Blitzer even had a legal right to stop Wolfblitzzer0 from his posts; unless the posts were commercial advertising (which I doubt), Blitzer wouldn't have a right of publicity or trademark claim against Wolfblitzzer0. And I doubt Blitzer would have a libel claim (on the theory that Wolfblitzzer0 is hurting Blitzer's reputation by posting things under his name) because few readers would really think that the poster is Wolf Blitzer.

But second, Blitzer certainly has no legal duty to spend his time, money, and effort litigating over every schmoe's misuse of his name -- even if he had a legal right to stop such misuses -- especially when readers would realize that the poster isn't the real Blitzer. (Under the doctrine of "apparent authority," A may sometimes end up bound by contracts that B made on his behalf, when reasonable observers would assume that B actually has the authority to act for A; but that surely isn't the case here.)

Sounds like a sure loser of a case to me, perhaps even sanctionable (though that's a tougher call).

Kyoto Comes into Force:

Yesterday the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change — aka the UN global warming treaty — came into effect. This became a done deal after Russia agreed to ratify the agreement. By its terms, Kyoto enters into force on the 90th day after at least 55 countries representing at least 55 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions in 1990 ratify the agreement.

Contrary to some claims, the U.S. never "withdrew" from Kyoto the way it withdrew from the International Criminal Court. The U.S. remains a party. Nonetheless, this nation is not bound by its terms because the U.S. has not ratified it. Most other developed nations have ratified Kyoto, however, and are bound by its terms — at least in theory. Many of Kyoto's signatories in Europe are well behind their emission reduction goals, and developing nations are not required to reduce their emissions at all. As Julian Ku notes at Opinio Juris, many Kyoto signatories are heading in the "wrong direction."

The Bush Administration has been the subject of substantial criticism for refusing to endorse Kyoto. But is this criticism warranted? The Clinton Administration signed the treaty, but never submitted it to the Senate for ratification. The Senate passed the Byrd-Hagel Resolution 95-0, unanimously rejecting the substance of the agreement. Even some who believe global warming is a pressing policy concern doubt Kyoto represents a responsible strategy to address climate change concerns.

The underlying assumption of much anti-Bush Kyoto commentary is that the Bush Administration is doing nothing on the issue. Even if one sets aside the tens of millions the administration has spent on climate-related research and technology R&D on the assumption that such federal projects rarely bear fruit, the charge that the Administration is sitting on its hands rings hollow. As Gregg Easterbrook notes in The New Republic, the Administration's "Methane to Markets" initiative represents a substantial step toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions. (For non-TNR-subscribers, Julian Ku summarizes the article here.) While few have noticed this program, it could do as much to reduce the threat of global warming as Kyoto as methane is a more potent greenhouse gas than CO2.

Despite its promise, I would not expect too many environmental activists to cheer "Methane to Markets." First, as we have seen in other contexts (see here and here), the major environmental groups are loathe to give a conservative Republican administration much credit for any environmental initiatives. Second, although "Methane to Markets" could bear fruit, it does not require stringent regulations of coal-fired power plants, limitations on fossil fuels, or controls on SUVs. Third, as Ku suggests, there is often a preference for grand international agreements (like Kyoto) over less-formal — but not necessarily less-effective — agreements like "Methane to Markets." It will be interesting to see whether this agreement is a one-shot deal, or a harbringer of more to come.

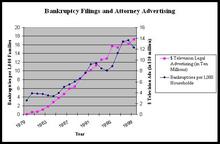

Chart on Attorney Advertising and Bankruptcy:

I have a very busy day, so I don't have time for another long post on bankruptcy reform (I'll get back to it tomorrow I hope if I have time), so I'll just leave you with a self-explanatory chart on trends on attorney advertising and bankruptcy filings that is contained in my latest article:

Numerous caveats apply--this is just tv, it is all advertising and not just for bankruptcy, etc. So I'll just let you make of this what you wish and leave it at that.

Update:

2 points. First, I made no claim about causation in my original posting--there could be no causal link at all here and if there is correlation, it could be spurious. If there is a causal link, it could run in either direction (e.g., public demand for bankruptcy lawyers could lead to more advertising). Second, there is a very well established empirical literature that advertising for legal services increases demand for legal services, so that the relationship is theoretically possible, unlike, for instance, other random correlations that some have drummed up. I thought the underlying model was obvious, but apparently some who criticized me weren't aware of this vast body of academic literature. And, of course, there is other empirical evidence that finds some sort of relationship between lawyer advertising and bankruptcy filings, although again, existence and direction of causation remain open. Whether this particular chart provides any additional empirical evidence or intuition to support the theory, as I said once already, I leave to you. But that doesn't mean the theory doesn't make any sense.

Wednesday, February 16, 2005

Monday's Talk at Quinnipiac:

Although it is not yet on their website, my talk on Monday (2/21) on Ashcroft v. Raich at Quinnipiac University School of Law has been scheduled for noon in the Grand Courtroom. The event is open to the public.

Also next week, I will be speaking at Cumberland Law School Birmingham AL (noon - 2/24) and at the University of Alabama School of Law in Tuscaloosa (noon - 2/25).

Forward-Thinking Universities:

I just noticed that a university other than UC was smart enough to snag uc.edu before UC did. Likewise, I've long noticed that one particular school is law.edu. If anyone has other examples of universities that have such domain names -- names that do match the school's name or field, but that seem to reflect the school's wisdom in being first to snag a name that other more prominent schools might have also wanted -- please leave them in the comments.

Interesting Star Trek Initiative (UPDATE: NEVER MIND):

A reader just passed along to me this link to an interesting posting by J. Michael Straczynski, the creator of Babylon 5. (Volokh readers have much praised Babylon 5 to me but I could never get into it during its first run.) After a discussion of how the Star Trek franchise evolved to this point, here is how it provocatively ends:

Last year, Bryce [Zabel (recently the head of the Television Academy and creator/executive producer of Dark Skies)] and I sat down and, on our own, out of a sheer love of Trek as it was and should be, wrote a series bible/treatment for a return to the roots of Trek. To re-boot the Trek universe.

Understand: writer/producers in TV just don't do that sort of thing on their own, everybody always insists on doing it for vast sums of money.

We did it entirely on our own, setting aside other, paying deadlines out of our passion for the series. We set out a full five-year arc.

But when it came time to bring it to Paramount, despite my track record and Bryce's enormous and skillful record as a writer/producer, the effort stalled out because of "political considerations," which was explained to us as not wishing to offend the powers that be.

So on behalf of myself and Bryce, I'm taking the unusual step of going right to the source...right to you guys, fueled in part by a number of recent articles and polls, including one at www.scifi.com/scifiwire in which nearly 18,000 fans voted their preference for a new Trek series,

and 48% of that figure called for a jms take on Trek. (The other choices polled at about 18% or thereabouts.)

See, if somebody doesn't like a story, doesn't want to buy it, that's all well and good, that's terrific, that's the way it's supposed to be.

But when "political considerations" are the basis...that just doesn't parse.

So here's the deal, folks. If you want to see a new Trek series that's true to Gene's original creation, helmed by myself and Bryce, with challenging stories, contemporary themes, solid extrapolation, and the infusion of some of our best and brightest SF prose writers, then you need to let the folks at Paramount know that. If the 48% of the 18,000

folks who voted at scifi.com sent those sentiments to Paramount...there'd be a new series in the works tomorrow.

I don't need the work, I have plenty of stuff on my plate through 2007 in TV, film and comics, so that's not an issue. But I'd set it all aside for one shot at doing Trek right, and I know Bryce feels the same. Update: NEVER MIND! Here is a follow up post from J. Michael Straczynski:

Actually...belay everything I just said.

In the 24 hours between the time I composed the prior note, and sent it, and it made its way through the moderation software, two things happened:

1) I heard from a trusted source that Paramount is giving the Trek TV world a rest for maybe one to two years, depending on circumstances, no matter who would come along to run it. So it's not right to have folks putting in time doing something that ultimately would be pointless, I don't think that's a proper use of anybody's time.

2) At the same time as the above, an offer came in to run a new TV series for fall of '06, and since there's no way anything Trek can happen in the interim, I've said yes (now we have to negotiate the deal, but that should be fairly straightforward).

So on two counts, the whole thing is kind of moot.

We can reconvene a year or two down the road to see where this takes us, but in the interim...my apologies for waking everybody up in the middle of the night.

As you were. Well, THAT was fast!

New Daily Feature on NRO:

In addition to The Corner and TKS (formerly "The Kerry Spot"), National Review Online is now offering the Beltway Buzz. Here is its introduction:

Welcome to Beltway Buzz

02/15 01:10 PM

We're constantly thinking of new ways to make NRO bigger and better. With that general goal in mind, today National Review Online introduces a new feature: "Beltway Buzz," which promises to be required reading for anyone looking for Washington, D.C.-focused news and analysis.

We're delighted to have Eric Pfeiffer, formerly of National Journal's sweet daily political candy, "The Hotline," on board to be your daily Beltway buzzer. Welcome, Eric and welcome new Beltway Buzz bookmarkers. Enjoy.

— Kathryn Jean Lopez, Editor, National Review Online

Here It Begins

02/15 01:13 PM

Welcome. I'm Eric Pfeiffer and I'll be your Buzz guy.

This page is now home to a daily feature that aims to provide readers with a fresh look at news and analysis from inside Washington.

First, a little background on me: For the past three years I wrote for "The Hotline," a daily political briefing published by the National Journal. While at "The Hotline," I contributed articles regularly to NRO, The Weekly Standard, the Americas Future Foundation, and others. Early risers can also find me occasionally offering weekly political analysis with ABC News Now.

My main focus here is to provide readers with a fresh angle on political news: the story behind the story you get on the evening news, the counter-story to the conventional wisdom of the day, etc. The Beltway Buzz will be a filter for anyone who wants to be in the know. And it will break some news, too.

And we're on the Internet, so feedback is easy to provide and is encouraged. My e-mail is efeiffer@nationalreview.com — so you know where to find me.

Thomas Woods's "Politically Incorrect Guide to American History":

Max Boot (not a particularly politically correct fellow himself, writing in the not very politically correct Weekly Standard) criticizes it forcefully and in detail.

Boot also points out the error in the New York Times Book Review's characterization of the book as a "neocon retelling of this nation's back story," faults Regnery, Woods' publisher, and warns conservative consumers: "Conservatives looking to inoculate themselves or their children from liberal indoctrination would be well advised to steer clear of Woods's corrosive cornucopia of canards."

Good for You:

First alcohol, now coffee (though unfortunately maybe decaf is best).

Of course, "That difference may, however, be due to differences in lifestyle, the researchers commented, suggesting that drinkers of decaffeinated coffee might be more health-conscious overall." But, hey, I know how to ignore scientific disclaimers just as well as the next guy.

New Study on Dynasty Trusts and the Abolition of the Rule v. Perpetuities.--

The Wall Street Journal has a story today on a pathbreaking new study just completed by two of my brilliant young Northwestern colleagues, Rob Sitkoff and Max Schanzenbach. Unfortunately, the Journal's article is available only to subscribers, but the Journal's story is already up on Westlaw (2005 WL-WSJ 59841238) for academics who have that subscription.

The study (which can be freely downloaded from SSRN) examines whether trust assets are moving into states that repealed the Rule v. Perpetuities and thus permit perpetual dynasty trusts. Rachel Silverman in the Journal explains:

Until recently, trusts could effectively last only about 90 to 120 years, under a law called the Rule Against Perpetuities. Since the mid-1990s, a growing number of states moved to relax the term limits. Now, at least 18 states and jurisdictions — including Delaware, Wisconsin, New Jersey, Illinois, Virginia and the District of Columbia — allow trusts to last forever. Several states that impose term limits allow much longer durations. Wyoming and Utah, for instance, permit trusts to last 1,000 years, while Florida lets them carry on for 360 years.

To set up a dynasty trust, it isn't necessary for families to live in a state that permits them. Only a trustee has to be located there — and many trust companies have operations in Delaware, Florida or other states that welcome long-term trusts. Moreover, some of those states, such as Alaska, have other trust-friendly benefits, like no state income taxes on trusts and strong asset-protection laws.

The study found that simply changing a state's perpetuities laws wasn't enough to attract trust assets. Whether a state levied income tax on trust funds mattered, too. If a state abolished its rule against perpetuities, but still taxed trust funds attracted from out of state, the researchers found "no observable increase" on a state's reported trust assets. By contrast, if a state allowed dynasty trusts but also didn't tax trust funds created by nonresidents, the state's reported trust assets increased by roughly $13 billion on average during the time period studied.

The study finds that a lot of trust money has been flowing into South Dakota, Delaware, and Illinois (among others)--states that repealed the Rule v. Perpetuities and have no fiduciary income tax on trusts holding assets for out-of-state beneficiaries.

Here is the abstract to the scholarly paper:

Jurisdictional Competition for Trust Funds: An Empirical Analysis of Perpetuities and Taxes

This paper presents the first empirical study of the jurisdictional competition for trust funds. In order to open a loophole in the federal estate tax, a rash of states have abolished the Rule against Perpetuities. Based on reports to federal banking authorities, we find that through 2003 a state's abolition of the Rule increased its trust assets by $6 billion (a 20% increase on average) and increased its average trust account size by $200,000. These estimates indicate that roughly $100 billion in trust funds have moved to take advantage of the abolition of the Rule. Interestingly, states that levied an income tax on trust funds attracted from out of state experienced no increase in trust business from abolishing the Rule. This is a striking finding for the theory of jurisdictional competition, because it implies that abolishing the Rule does not directly increase a state's tax revenue. These results also have relevance for theories relating to altruism and the bequest motive. The main tax benefits of establishing a perpetual trust accrue not to the donor or anyone she knows, but to beneficiaries whom the donor has never met - the unborn.

The study will be important to academics because it is the first major empirical paper on the competition among states for trust business. Academics know that there is a massive empirical literature in corporate law on state competition for corporate charters, but (until now) there has not been a similar literature in Trusts & Estates.

Sitkoff and Schanzenbach's conclusion: If you build it, they will come.

Hot tip for any law review editors reading this blog: Check your mailboxes over the next few weeks; in its field this article will be a blockbuster.

FTC Study on On-Line Sales of Replacement Contact Lenses:

Important new study of competition and consumer protection issues involving on-line sales of replacement contact lenses can be found here.

Great example of how the FTC can use its research tools to advance understanding of market competition furthers consumer welfare and how wrongheaded professional licensing requirements can harm consumers.

The Other Bankruptcy Blogger:

Apparently there are two of us now who blog on bankruptcy issues. For those who prefer a "front lines" analysis (and a bit more "colorful" take) rather than my academic analysis of bankruptcy reform, see the State 29 blog.

With 2 of us, I think that pretty much satiates the public's appetite for bankruptcy-related blogs.

Update:

Whoops, Kemplog points out that I missed one--Automatic Say. So there are three of us--soon we will overtake all those Constitutional Law blogs out there!

Health Problems and Bankruptcy--Are 50% of Bankruptcies Health Related?:

In Senate testimony last week, one of those testifying offered the observation, "One million men and women each year are turning to bankruptcy in the aftermath of a serious medical problem—and three-quarters of them have health insurance." In a column in the Washington Post last week, Professor Elizabeth Warren (who also gave the just quoted testimony) stated, "[H]alf [of bankruptcy filers] said that illness or medical bills drove them to bankruptcy," an assertion that was repeated at the Hearings last week on the bankruptcy reform legislation. Most of the Democratic Senators in attendance accepted the assertion that 50% of bankruptcies are caused by health problems without question (even going so far as to silence me when I raised doubts about the credibility of that figure). It has also been widely reported in the media.

Professor Warren writes, "With the dramatic rise in medical bankruptcies now documented, this tired approach would be no different than a congressional demand to close hospitals in response to a flu epidemic." This figure was used to throw cold water on the bankruptcy reform legislation, and it is expected that Sen. Feinstein at least will propose an amendment.

But is it true that it is "now documented" that 50% of bankruptcies are caused by health problems?

The conclusion is based on a study in Health Affairs. Reviewing the study, it appears that the estimate that 50% of bankruptcy filings are precipitated by a "serious medical problem" cannot be supported based on what that study actually examined.

First, the study comes on the heels of many studies over many decades that find mixed evidence for the belief that a substantial number of consumer bankruptcies are caused by health problems. Those that did find some relationship often found a very small relationship, which explains why Professor Warren has described it as "a dramatic rise" in medical bankruptcies. For instance, in an earlier book, Professor Warren and co-authors wrote, "The central finding is that medical debt is not an especiallly important burden for most debtors." In a more recent article, it was observed that "until the 1990s . . . most empirical studies of bankruptcy did not find illness, injury, or medical debt to be a major cause of bankruptcy." Indeed, in the Health Affairs article, it is stated that medical bankruptcies increased 23-fold over the past two decades. No previous credible study has ever found anything approximating the conclusion that 50% of bankruptcies are caused by medical problems. The appearance of such a huge anomaly usually augurs caution in interpreting the results in light of the massive contrary results on the other side. Such caution is warranted here.

In fact, the "finding" in this article of a massive rise in medical bankruptcies appears to actually be a result in the way in which medical bankruptcies are counted, rather than an actual change in the numbers. They draw their data from two sources. First, self-identified bankruptcy filers who say that some medical event "caused" their bankruptcy. Second, analysis of "objective" facts on filers bankruptcy papers that find either (1) debtor or spouse lost at least 2 weeks of work-related income because of illness or injury or (2) uncovered medical bills exceeding $1,000 in 2 years before bankruptcy, or (3) debtors who say they had to mortgage their home to pay medical bills (which for some reason they list as an "objective" factor rather than a self-identified factor.

Do these findings support the claim that 50% of bankruptcy filings were caused by a "serious medical problem"?

First, consider the self-identified filers. Among the self-identified factors that are listed as "medical" causes of bankruptcy in Exhibit 2 of the article are the following: illness or injury, birth/addition of new family member, death in family, alcohol or drug addiction, uncontrolled gambling. First, it is surely open to question whether uncontrolled gambling or a death in the family really should count as a "medical" problem. More generally, the category "illness or injury" is very broadly defined in the study, and there is no apparent limit on the time frame over which the illness or injury occurred, or the severity. So classifying all of these factors as medical problems that have "caused" bankruptcy certainly seems open to question.

Second, the "objective" measures from the debtors bankruptcy petitions are, if anything, even more questionable. First, the authors count anything above 2 weeks of lost work income as a "serious medical problem." There appears to be no time frame over which this is measured, nor does it apparently even need to be consecutive lost work. So, for instance, if a restaurant waiter called in sick for 2 weeks or more in some indeterminate period of time prior to filing bankruptcy, this would presumably count as a serious medical problem.

Nor does the requirement of $1,000 in unpaid medical bills within 2 years of bankruptcy seem like a very plausible measure of serious financial problems. Again, it is pretty easy to rack up $1,000 in unpaid medical bills over a 2 year period, especially if elective procedures not covered by insurance are added in. Moreover, it is well-understood that debtors who are falling into bankruptcy pick and choose which debts they pay, paying down their mortgage or nondichargeable debts for instance, while not paying their unsecured debts, such as medical and credit card debt. So the fact that the medical debts were unpaid says little, because it may reflect strategic payment of debts prior to bankruptcy.

So the categorization of what counts as a "serious medical problem" is quite questionable in this study. But there is a more fundamental problem that this concern hints at--there is no control group in this study. It is usually Statistics 101 that in order to infer causation from a data observation, it is necessary to have a control group. Absent a control group, it is not clear how the authors can make their claims.

So, for instance, one would want to know how many Americans missed 2 weeks of work or had a $1,000 in medical bills and didn't file bankruptcy. This is precisely why other previous studies have failed to find much of a correlation between health problems and bankruptcy--almost every family in America has a health problem, death in the family, or gives birth every year. Most of them do not file bankruptcy. In short, I suspect a lot of people had medical problems comparable to those who filed bankruptcy, but did not file bankruptcy. Of course, we will never know, because the authors have no control group to determine whether those in bankruptcy were more prone to illness or injury than the population at large.

Moreover, the authors do not compare the amount of medical debt they found to other debt or obligations that bankrupt debtors had. So, for instance, they would count as a medical bankruptcy a debtor who had $1,001 in medical bills, even if that debtor had say $50,000 in student loans, car loans, and other debt. It would be absurd, it seems to me, to say that the $1,001 in medical expenses "caused" that bankruptcy. Nonetheless, it would counted in this study, because the authors do not control for medical debt as a percentage or in relation to the debtors overall debt.

But the problems do not end there. For instance, the authors claim (page W5-71) that from 1981-2001, medical bankruptcies increased 23-fold, citing a study from 1981 published in "As We Forgive Our Debtors." I have read and reread the relevant chapter of that book, and have been unable to determine exactly what criteria were used to classify medical bankruptcies there, and how they compare to here. It appears that the measure used in the earlier work was the pure narrowest form of self-identified filers, those who stated that they filed bankruptcy because of a health problem. In the current study, it appears the authors ask the self-identified filers if health problems were "a reason" for bankruptcy. I can find no evidence that the authors there counted as medical bankruptcies any bankruptcy where the debtor had above a specified amount of medical expenses. Even if it were the case, there is no evidence that the $1,000 figure chosen in the current study was adjusted for inflation over the prior study. Nor is there any indication that the authors attempted to adjust the medical expenses that are found in the current study for increases in debtor's income. So again, it seems like they have just changed their method of counting, not the actual substance.

The authors also do not provide any causal explanation for what could have changed in the medical system to produce a 23-fold increase in health=related bankruptcies in 20 years, and specifically note that the percentage of those in bankruptcy who have health insurance has changed little over that time.

In fact consider the following passage from "As We Forgive Our Debtors":

Our central finding is that crushing medical debt is not the widespread bankruptcy phenomenon that many have supposed. To the extent that the typical debtors in bankrutpcy are painted as sympathetic characters because they are struggling with insurmountable medical debts, these data show that 'typical' is the wrong adjective. Only a few debtors find thmselves in such extreme circumstances.... About half of all debtors carry some medical debt, and many carry substantial medical debt. Althought these medical debts are not the obvious cause of the debtors' bankruptcies they are part of their financial troubles." (p. 173).

Again, what seems to have changed is not the frequency of the underlying problem, but simply the way the data is counted and classified. In the earlier study, the authors noted that half of filers had some amount of medical debt, but recognized that relatively small amounts of unpaid unsecured medical debt or minor injuries were likely not the cause of bankruptcy, because this is a part of the financial life for almost every American family. For the debtors in the earlier study, the medical debt that was found was relatively small in comparison to the bankrupts' other debts. In the more recent study, the authors have simultaneously increased what counts as a "medical problem" and classified even relatively small and trivial medical expenses and problems as bankruptcies "caused" by medical problems. Changing the way you count and classify the same data is not the same thing as finding a 23-fold increase in the underlying problem itself.

I close with an illustration that tries to put the major flaws of this study in perspective and the policy recommendations that have been drawn from it. Suppose that I wanted to find out how many Americans filed bankruptcy because of tax problems. I then interviewed bankruptcy filers and checked their financial records, and counted as a "tax-caused bankruptcy" anyone who either (1) paid $1,000 or more in taxes during the past two years, or (2) anyone who said that if he didn't have to pay taxes he wouldn't have had to file bankruptcy because he would have had more money for his other bills. I suspect that under that criteria I would find a pretty substantial number of "tax-caused bankruptcies." I then conclude that, as a result, we shouldn't make people pay taxes if they believe it might make them file bankruptcy, and that any unpaid tax obligations should get a blanket discharge in bankruptcy (unlike current law, which makes them largely nondischargeable).