|

|

Alexander "Sasha" Volokh

My tour of the Middle Ages, part II

London, England, March 25-29, 2000

Below: Nine pictures from Mme Tussaud's wax museum

Above: Me and William the Conqueror, plotting the invasion of

England

Above: Me and King Richard Lionheart, contemplating the Holy

Land.

Above: "Johnny, you've just gotta sign Magna Carta!"

Above: Me and Lenin, we're buddies.

See also a similar scene, 10 years ago.

Above: Me, a realistic Gorbachev, and a somewhat pasty-looking

Yeltsin.

Above: Me and Cardinal Newman, trying to distinguish

the Anglicans from the Monophysites.

Above: The head of Tom Baker, my favorite (the third?) Doctor

Who.

With him, Meglos the Cactus.

Above: Me and Joanna Lumley of Absolutely Fabulous.

Above: Fergie.

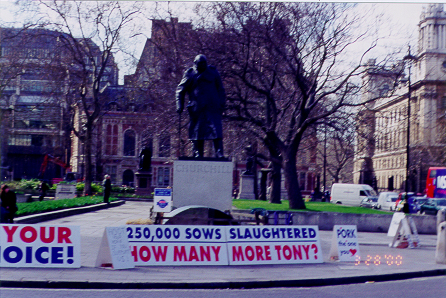

Below: Outside the Houses of Parliament, English pig farmers

display signs bemoaning their lot.

Churchill appears in the background of the last picture.

Below: Three pictures from the Tower of London.

The quoted passages are from The Tower of London, the English

Heritage guidebook.

Above: The White Tower (Tower of London)

"The White Tower is the most imposing and historic building in the

whole fortress.

It now contains displays from the Royal Armouries' collection,

telling the story of the building, as well as of arms and armour at

the Tower."

The White Tower was put in a slightly earlier fortified enclosed

created by William the Conqueror.

The date building began is traditionally given as 1078; it may have

been the work of Gundulf, Bishop of Rochetser, a renowned builder of

castles and churches.

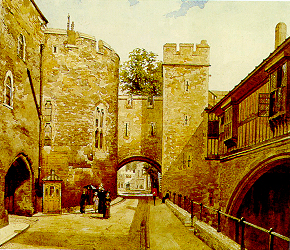

Above: The Tower Green (Tower of London)

"Tower Green is in the south-west corner of the Inner Ward which is

entered from Water Lane.

It has been an area of garden for probably 300 years and is bounded

on its south and west by a range of buildings which have

traditionally accommodated Tower of London officials, and still do

today."

The Tower Green is surrounded by the Bloody Tower, the Queen's

House, the Beauchamp Tower, the Scaffold Site, and the Chapel Royal

of St. Peter ad Vincula.

The Bloody Tower was built in the early 1220s but the upper stage of

the present tower was largely reconstructed in about 1360 under

Edward III.

After 1280, it became the principal access from the Outer Ward to

the Inner Ward.

Eminent prisoners of the Bloody Tower include the "Princes in the

Tower" (Edward and Richard, sons of Edward IV, imprisoned after 1483

and supposedly killed on the order of Richard III), Archbishop

Thomas Cranmer (1553-54), and Sir Walter Ralegh (1603-16).

The Queen's House was home to Guy Fawkes (1605) of the Gunpowder

Plot, both before and after his torture.

The Beauchamp Tower was built under Edward I in about 1281.

The Scaffold Site was where Anne Boleyn (1536), Catherine Howard

(1542) (Henry VIII's second and fifth wives), and Lady Jane Grey

(queen for eight days in 1553), among others, were executed.

Everyone who died on the Scaffold Site, as well as other famous

Tower prisoners, is burned in the Chapel Royal of St. Peter ad

Vincula.

Above: The Medieval Palace (Tower of London)

"The group of buildings known today as the Medieval Palace... was

generally used by the kings of England when in residence." The

Medieval Palace includes St. Thomas's Tower, the Wakefield Tower,

the Wall Walk, and the Lanthorn Tower.

"St. Thomas's Tower was built by Edward I between 1275 and 1279 to

perform a dual function, providing additional royal accommodation

for the King but also creating a new watergate at which the King

could arrive from the river.

This is now known as Traitors' Gate because it was through here that

prisoners accused of treason arrived from Westminster."

The Wakefield Tower "is the second largest in the Tower of London,

after the White Tower.

It was built between 1220 and 1240, in the reign of Henry III

(1216-1272) as an addition to the earlier palace buildings which he

enlarged and improved.

In addition to containing the King's principal private room it was

also a strongpoint in the Tower's enlarged defences.

Then standing directly on the river's edge, it commanded on one side

what was then the main watergate (later incorporated into the Bloody

Tower) and on the other side a small postern, the King's private

entrance from the river."

The Lanthorn Tower was built at the same time as the Wakefield

Tower, but it was destroyed in the 18th century and reconstructed,

and now "contains a number of 13th-century artefacts which

illustrate life in the palace of Edward I."

The next 12 pictures below are from manuscripts displayed at

the Chapter & Verse: 1000 Years of English Literature

exhibit at the British Library.

You should be able to blow up the pages to readable size by making

your browser display the images separately (View Image).

Quotes are from the British Library's guidebook to the exhibit.

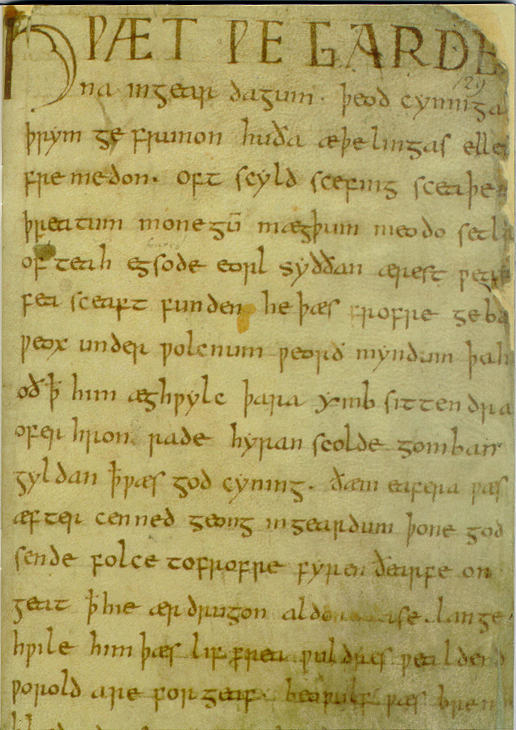

Above: Beowulf

"Some time around the year 1000 an anonymous scribe wrote down the

epic Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf.

The author of the poem is not known and it has been suggested that

it developed orally from as early on as the seventh-century.

Other copies of the poem may have been made but this is the only one

known to exist.

"The poem tells the story of Beowulf, a fifth- or sixth-century

Scandinavian warrior hero, who rids the Danish kingdom of a terrible

monster, Grendel, and his vengeful mother.

His prowess is rewarded with a gift of lands, which he rules in

peace for fifty years.

A dragon, revenging the theft of a goblet from its hoard, attacks

Beowulf's people and he once again goes into battle.

Although the dragon is killed with the help of a loyal subject,

Beowulf is mortally wounded.

His funeral pyre and a prophecy of disaster for the kingdom provides

a magnificent and terrible conclusion to the poem.

"Beowulf is a complex poem which works on many levels.

Most simply, it is a powerful and compelling tale of a great man's

battles with monsters.

It can also be read, however, as a remarkably perceptive examination

of early power politics, an allegorical account of the conflict

between early Christian and Pagan religious codes, or as an

archetypal examples of a story of good versus evil.

Well over 1000 years after its composition it continues to be taught

in the original Anglo-Saxon as a founding text of the English

literary tradition.

Perhaps more importantly (and especially when translated by a poet

as gifted as Seamus Heaney [see below]), it is increasingly read for

sheer pleasure."

The picture shows the first page of Beowulf: "Hwaet we garde

/ na in geardagum theodcyninga," meaning "Lo! we [have heard] about

the might of the Spear-Danes' kings in the early days."

Above: Pearl, by the Gawain poet (fl. c. 1380),

Cotton Nero A. X, f. 42

"The author of Pearl remains one of the most mysterious

figures in English literature.

We know little other than that he was probably attached to a noble

house in the North of England in the late fourteenth-century and

that his four known poems -- including Sir Gawain and the Green

Knight -- survive only in this manuscript, which includes

several illustrations.

"The poem describes a father's anger, sorrow and incomprehension at

the loss of his infant daughter, or 'Pearl.'

Dreaming upon her grave, he sees her on the other side of a river,

grown up and radiantly dressed.

She reproaches him for his sorrow but, overcome with longing, he

plunges in to join her.

Although he soon awakes, still a grieving man in the mortal world,

he is able to find some consolation in the thought that his daughter

is now a 'queen of heaven.'

The manuscript here shows the father's amazed reaction on seeing his

daughter, a moment translated from the text of the poem by J.R.R.

Tolkien:

"'O Pearl!' said I, 'in pearls arrayed,

Are you my pearl whose loss I mourn?

Lament alone by night I made,

Much longing I have hid for thee forlorn,

Since to the grass you from me strayed."

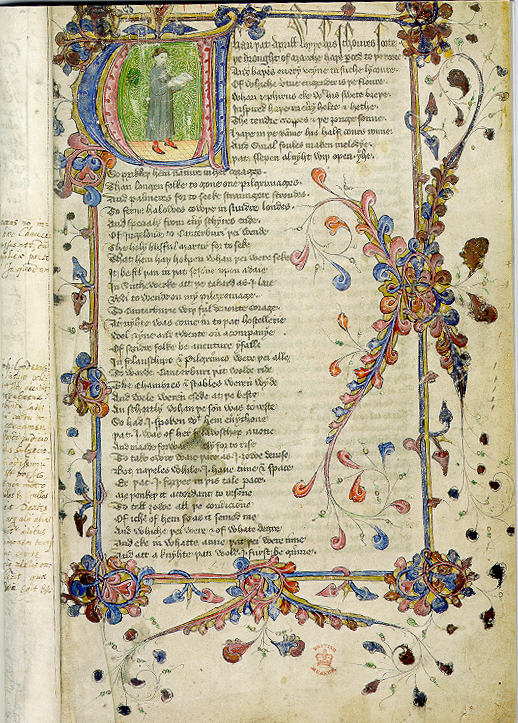

Above: The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer (c.

1343-1400), Lansdowne MS 851, f. 2

"Geoffrey Chaucer, a charismatic and adventurous civil servant, was

credited by a friend as being 'the first finder of our fair

language.'

At a time when most important poetry was written in Anglo-Norman or

Latin, his brilliant use of English played a central role in

establishing the literary language we recognise today.

The Canterbury Tales, blending supreme narrative skill with

an extraordinary talent for characterisation, is Chaucer's comic

masterpiece: every social type is teased in the pilgrimage from

Southwark to Canterbury, including the author himself.

"Chaucer is the first English writer to have been accurately

represented in portraits -- although these are extremely rare.

This early manuscript copy of The Canterbury Tales opens with

an illustration of the poet reading.

His surprisingly sober expression is more than made up for by his

jaunty red socks."

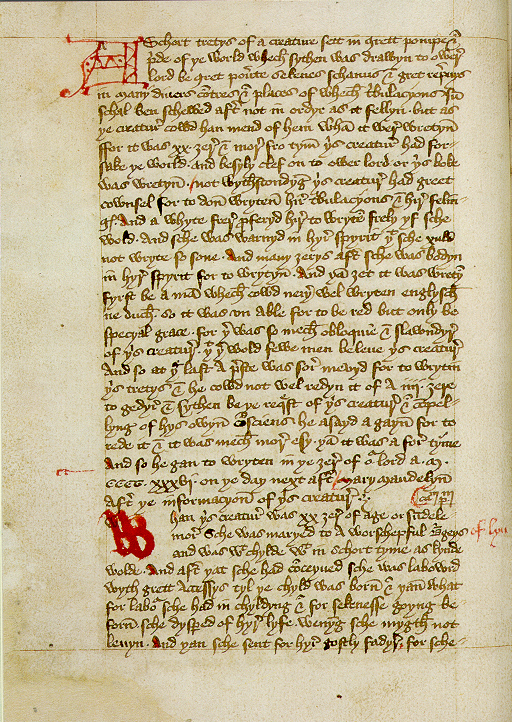

Above: The Book of Margery Kempe by Margery Kempe (c.

1373-c. 1439), Add. MS 61823

"The earliest surviving autobiography written in the English

language was discovered in 1934, some five hundred years after its

composition, by a man search for a lost table-tennis ball.

It describes the extraordinary and adventurous life of a Norfolk

woman whose early temptations led her, much to the annoyance of her

husband, to follow a life of devotion, pilgrimage and chastity.

"The account was first dictated by Kempe and then written down by a

scribe shortly after her death.

Before its remarkable discovery, all that was known of the work were

seven extremely rare pages of extracts printed by William Caxton's

one-time assistant, Wynkyn de Worde, in 1501."

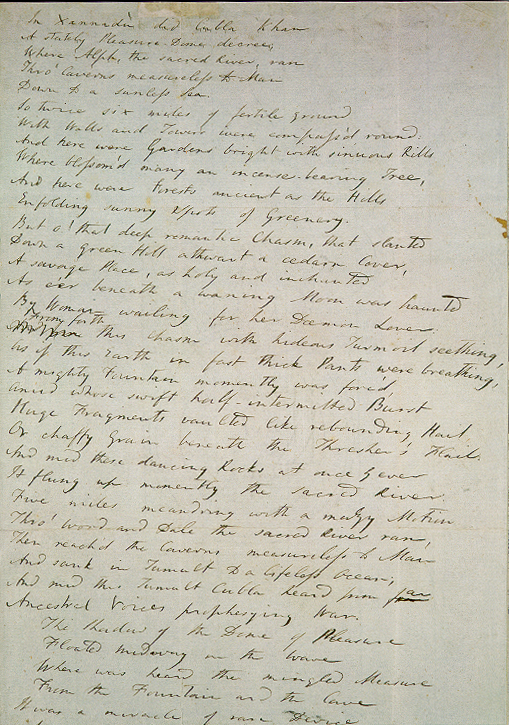

Above: "Kubla Khan" by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834), Add.

MS 50847, f. 1v

"'Kubla Khan,' one of literature's most famous, discussed and

puzzled-over creations, survives here in one of its most celebrated

and curious manuscripts.

At the end of the poem, Coleridge records the mysterious

circumstances of its composition:

"'This fragment with a good deal more, not recoverable, composed,

in a sort of Reverie brought on by two grains of opium, taken to

check a dysentry, at a Farm House between Porlock & Linton, a

quarter of a mile from Culbone Church, in the fall of the year,

1797'

"The account conflicts with the version Coleridge published in 1816,

in many details of time, place and circumstance, including the

omission of the famous interruption by the 'person on business from

Porlock.'

The actual events leading to and surrounding the composition of this

imaginative masterpiece look likely to remain forever uncertain."

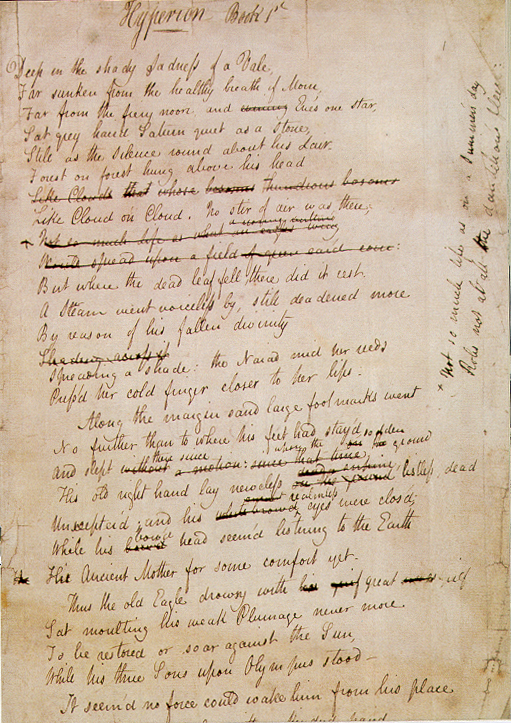

Above: "Hyperion" by John Keats (1795-1821), Add. MS 37000, f.

1

"This 'epic fragment' was begun in late 1818 in Hampstead and

published in 1820, just one year before its young author died of

tuberculosis in Rome.

"Hyperion" describes war among the ancient gods, with the old order

of Titans finally deposed by Apollo, god of poetry and music.

As so often in Keats's work, the subject seems to symbolise the

poet's own struggle for fresh inspiration.

"Keats, who trained as a doctor before turning to poetry, never

enjoyed literary success in his lifetime; his sadly ironic belief

that his work would remain unread after his death is reflected in

the words he chose for his grave in Rome: 'Here lies one whose name

is writ in water.'"

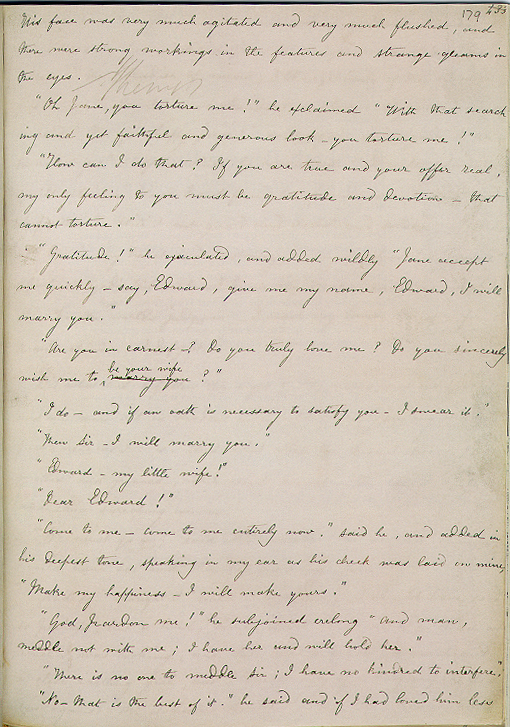

Above: Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte (1816-1855), Add. MS

43475, f. 179

"This is Charlotte Bronte's handwritten manuscript of Jane

Eyre, open at Rochester's proposal -- perhaps the most

celebrated in fiction.

The manuscript was sent by Charlotte to her printer in August 1847

after she had written the novel at great speed, spurred on by the

publication successes enjoyed that year by her sisters, Emily and

Anne, and undaunted by the rejection of her first novel, The

Professor.

It appeared in print just two months later and met with great

acclaim, fully answering her publisher's demands for a story of

'thrilling excitement.'

"The manuscript -- one of three volumes -- is remarkably neat, given

the speed with which Bronte worked, and has few corrections.

It provides a wonderful example of what Elizabeth Gaskell described

as her 'clear, legible, delicate traced writing.'"

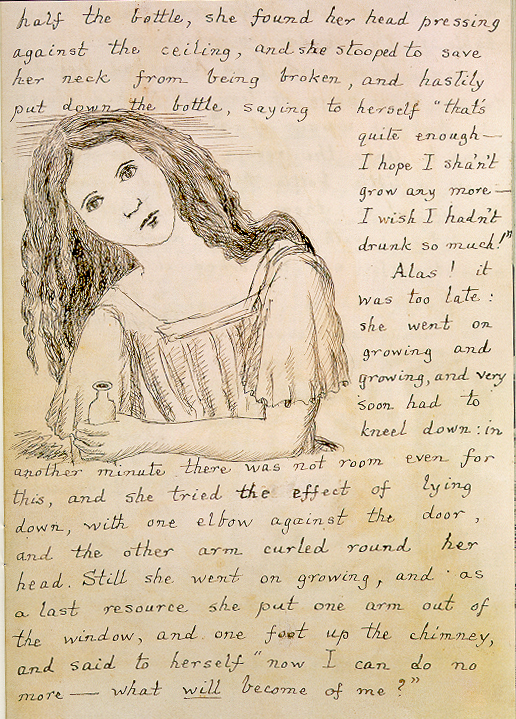

Above: Alice's Adventures Under Ground by Lewis Carroll

(1832-1898), Add. MS 46700, ff. 19v-20

"On 4 July 1862, the Reverend Charles Dodgson, a young mathematics

tutor at Christ Church, Oxford, entertained three little girls on a

river trip with an extraordinary and fantastic 'fairy tale' which

was to become one of the most famous children's stories of all time.

Alice Liddell, its ten-year-old heroine, begged him to write it out

for her, but had to wait two years until she received this

beautifully hand-written little volume, with Dodgson's own charming

illustrations, entitled Alice's Adventures Under Ground.

"In 1866 Dodgson published a revised and expanded version,

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, under the pseudonym 'Lewis

Carroll.'

The manuscript remained with Alice for many years, until financial

difficulties compelled her to sell it at auction in 1928.

It was purchased by an American collector but eventually returned to

Britain in 1946.

"The page shown here contains one of Dodgson's illustrations of

Alice after she has drunk from the 'little magic bottle' found in

the White Rabbit's house."

Above: Just So Stories by Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936),

Add. MS 59840, f. 33

"Kipling's Just So Stories are loved by children and adults

alike.

Shown here is the manuscript volume sent to the printer for

publication in 1902; it clearly demonstrates how Kipling's skill as

a writer was matched by his superb artistic ability.

"This is his illustration to the story of 'The Elephant's Child,'

which tells how a baby elephant of 'insatiable curiosity,' for which

he was frequently spanked, acquired his trunk.

Kipling describes the picture earlier in the manuscript:

"'This is the Elephant's Child having his nose pulled by the

crocodile.

He is much surprised and astonished and hurt, and he is talking

through his nose and saying, "Led go! You are hurtig be!"

He is pulling very hard, and so is the Crocodile; but the

Bi-Coloured-Python-Rock-Snake is hurrying through the water to help

the Elephant's Child....'

"Included among the other famous stories in this manuscript are 'How

the Camel Got His Hump' and 'The Cat That Walked by Himself.'"

Above: "The Adventure of the Missing Three Quarter" by Sir Arthur

Conan Doyle (1859-1930), Add. MS 50065, f. 2

"Of all literary characters who have taken on a life of their own,

Sherlock Holmes is perhaps the most famous.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle first breathed life into him in 1887, only to

kill him off at the Reichenbach Falls in 1893.

Public outcry, however, forced the author to resurrect him eight

years later in The Hound of the Baskervilles, and he went on

to survive another thirty-five stories.

"In this adventure, written in about 1904, Dr. Watson's narrative

soon turns to a worried consideration of his master's dangerous

tendency to addictive substances:

"'Now I knew that under ordinary circumstances he no longer

craved for this artificial stimulus but I was aware the fiend was

not dead but sleeping.'

"The manuscript was presented to the British nation on 22 May 1959

to mark the one-hundredth anniversary of the birth of Sir Arthur

Conan Doyle by a group of American well-wishers, together with the

Friends of the National Libraries and the Sherlock Holmes Society of

London."

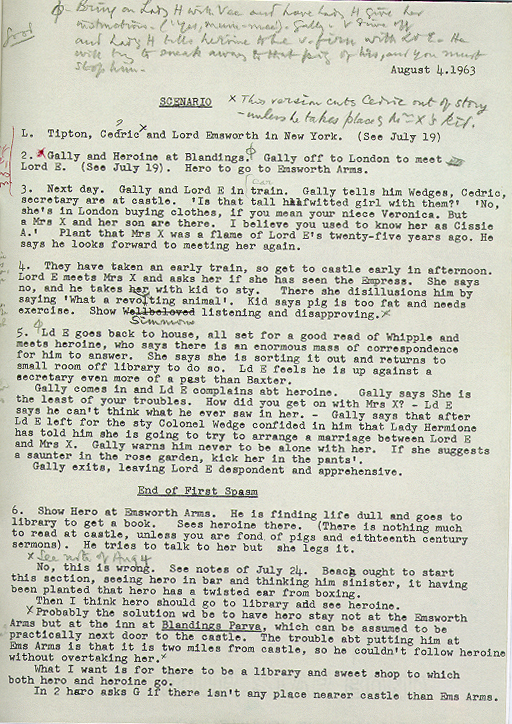

Above: Galahad at Blandings by P.G. Wodehouse (1881-1975),

Add. MS 52774, f. 95

"In 1903 P.G. Wodehouse gave up working as a bank clerk in order to

pursue his literary ambitions.

His life was as eventful as it was controversial.

During the Second World War he was captured in France by the

Germans.

Imprisoned at first, he was later released on condition that he

remained in Germany.

A number of subsequent broadcasts from Berlin about his captivity

provoked accusations of fascist sympathies.

After the war he settled in America, working for Hollywood and

producing numerous stories.

He gained American citizenship in 1955 and was awarded a knighthood

just weeks before his death.

"Perhaps most famous for the characters Jeeves and Wooster (who

first appeared in 1917), Wodehouse's inimitable comic flair is

instantly recognisable in a manuscript relating to the novel of

1965, Galahad at Blandings.

Wodehouse's extraordinary planning technique -- consisting of a

critical dialogue with himself -- is revealed here."

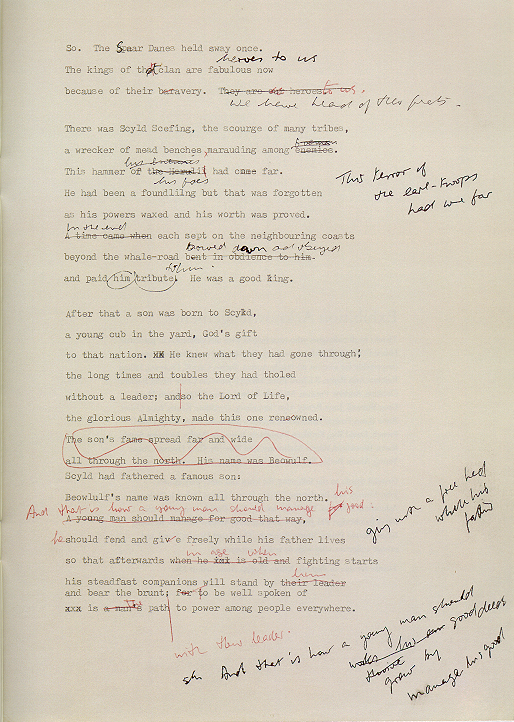

Above: Translation of Beowulf by Seamus Heaney (b. 1939),

Deposit 9896

"It has been said of Seamus Heaney that he 'is the one living poet

who can rightly claim to be the Beowulf Poet's heir.'

Some 1000 years after the original poem was set down in manuscript

[see above], the brilliance of his translation was recognised in

January 2000 when he won the Whitbread Book Award.

Heaney's poem faithfully captures all the power and subtlety of the

original, while enriching -- often clarifying -- its meanings in a

vernacular drawn from his own deeply-rooted Irish 'word hoard.'

"This page shows Heaney's first attempt to translate Beowulf

from the Anglo-Saxon text.

Dating from 1980, it was abandoned after only a few lines.

Fifteen years later, the poet took up his task again at Glanmore, a

spot which had already inspired a fmous and much-loved sequence of

sonnets.

This first and the many subsequent drafts of the opening of the

translation show the poet to be a tireless and careful crafter of

his work.

Heaney hones his typewritten text with annotations, corrections,

deletions and revisions, all marked in a vigorous and emphatic

hand."

Above: A sudden and very selective depressurization, in the

plane, on our landing back at Boston.

Advance to Greys Court

Return to places page

Return to home page

|