I recently blogged about United States v. Skinner, the new Sixth Circuit decision concluding that the Fourth Amendment does not protect location information obtained from a cell phone. Skinner has been getting a lot of attention in the blogosphere, in part because the facts are so vague, so decided to take a closer look at the case to see what I could learn about the facts in dispute.

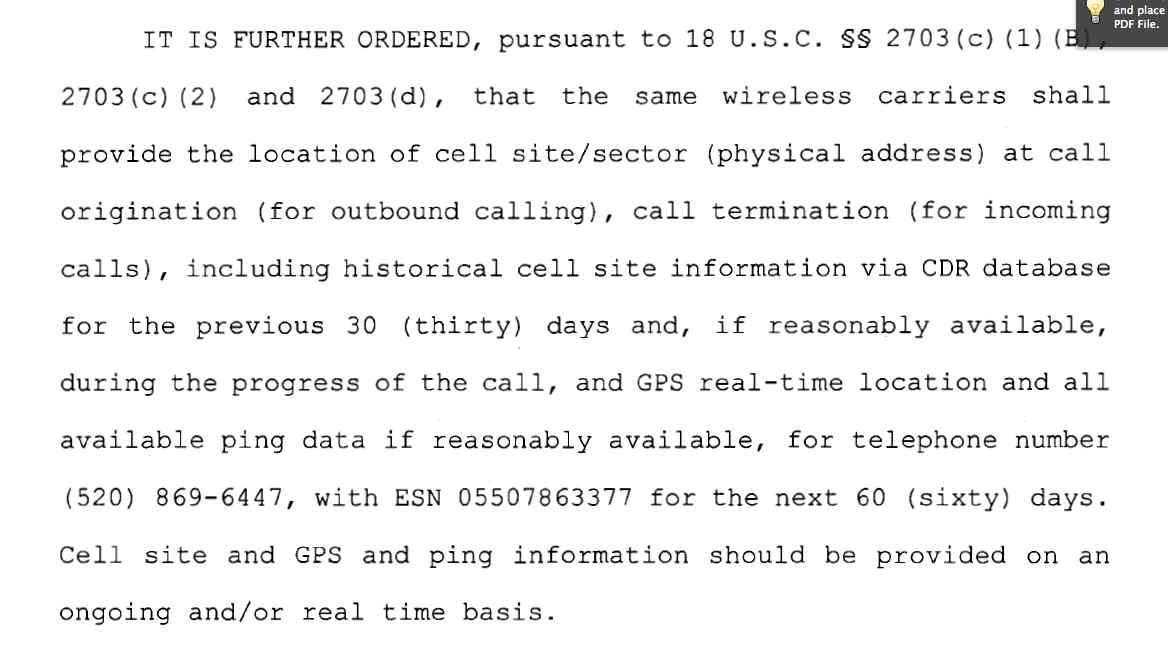

Here’s what I learned. First, here’s the first of the two court orders that the government obtained to compel the phone company to reveal location information. It’s one of the “hybrid” orders that DOJ has tried to use (or at least was using as of 2006, the date of the order) that combines several statutory authorities at once — pen trap, 2703(d), subpoena, etc. Putting aside the open question of the legality of such hybrid orders under statutory laws, the important part for Fourth Amendment purposes is what the court order allows the government to do in terms of location information. The order requires the phone company to provide the government with the following:

(This image may not be sizing correctly for some browsers. If you’re not seeing well, you can view it here.) As you can see, the order authorizes the government to get both cell-site and GPS information from the phone. So which did the government use when it “pinged” the phone? It’s somewhat hard to tell, because the magistrate judge’s Report and Recommendation refers to both GPS and cell-site and doesn’t focus much on the distinction. At the same time, the fact section of the magistrate judge’s Report and Recommendation refers primarily to GPS information, not cell-site data. Here’s the critical section, available at United States v. Skinner, 2007 WL 1556596 (E.D.Tenn. 2007):

Agent Lewis was given authorization to ping [FN9] the phone and ascertain its GPS location. He testified that he knew the phone had a GPS device installed in it based on the type of phones that allow minutes to be loaded onto them. Only a few models of telephones are available to those who opt not to subscribe to a wireless service but instead buy a phone which requires minutes to be loaded. After contacting the phone carrier, Agent Lewis learned the specifications for this phone and that it had GPS capabilities.

FN9. “Pinging” a cell phone garners the GPS or triangulation information. [Doc. 71-Tr. 74]. Technically, the phone company does the actual pinging, but the phone company will ping a phone at the government’s ordered request. [Doc. 71-Tr. 75]]

Once Agent Lewis pinged the phone, he discovered that it was in North Carolina. Agent Lewis testified that he immediately realized he had misunderstood previous intercepts of West’s conversations. He now realized that the “James Westwood” phone was the phone that West used to call Big Foot, not the phone in Big Foot’s possession used to call West. To ascertain the number of the phone being used by Big Foot, Agent Lewis called the phone company to get the toll records of all numbers dialed by the “James Westwood” phone. There were several calls, but all were to the help-line and to one other number, (520) 869-6820. The (520) 869-6820 number was registered to “Tim Johnson” and, based on the process of elimination, the agents knew it was the phone being used by Big Foot.

On July 13, 2007, Knoxville agents sought a new order, authorizing the agents to track the “Tim Johnson” phone. Though the actual affiant was Agent Davis, Agent Lewis testified they were working “hand in hand” throughout the investigation and application process. [Doc. 71-Tr. 61]. Agent Lewis also testified that he always relies, and relied in this specific instance, on the Assistant United States Attorneys to provide the correct legal bases to support the applications and affidavits. The agents obtained the order sought.

Acting on the authority granted by the Court, the agents obtained GPS information from the phone company. From this information, the agents learned that the “Tim Johnson” phone was in Arizona. From a wire intercept, they learned that the last load of marijuana had been transferred to the RV on July 13. They also learned that Big Foot was not going to begin his cross-country journey until July 14. The agents believed that, once loaded, the caravan would transport the marijuana to Tennessee, but through a wire intercept they learned that Big Foot was actually going to take the marijuana to his home. Because the agents did not know the exact location of Big Foot’s residence, and thus far did not know Big Foot’s identity, they decided their best course of action was to locate the vehicle and apprehend it on its way east.

The agents did not have anyone following the vehicles and conducting visual surveillance. Therefore, the Knoxville agents watched where the phone was located via GPS tracking with the goal of ascertaining the location of the couriers, Big Foot and his son. They learned that the phone was traveling on an interstate, I-40, on July 15 and moving east across Texas. While watching the phone travel, the officers intercepted a phone call. Agent Lewis testified that at 10:30 P.M. there was a call between, he believed, West and Apodaca, “and Apodaca was wanting to know the progress of the load of marijuana and where it was. And West made the statement that, ‘I just spoke to him and he told me that he’s going to be driving for another couple of hours before he rests.’ ” [Doc. 71-Tr. 50]. At that point, the agents realized the courier would be stationary soon and began to narrow their focus to which Texas office they needed to work with to apprehend the courier. The agents determined that the Lubbock, Texas DEA office would be the closest to where the RV was likely to stop for the night.

At around 2 A.M., the Knoxville agents noticed that an identical GPS reading was appearing. They realized that what West had said earlier was coming true; Big Foot was taking a rest for at least some period of time. Using the latitude and longitude data provided from the telephone company, the agents determined that the vehicle was located at a truck stop near Abilene, Texas.

As I read this, it seems to me that the location monitoring was obtained by ordering the cell-phone provider to contact the phone and have the phone send on its GPS coordinates, not by obtaining cell-site location information that the cell provider was collecting in the ordinary course of business. If that’s right, I think it is still correct that the monitoring did not violate a reasonable expectation of privacy under United States v. Knotts, the radio beeper case, at least so long as the monitoring only revealed the location of the phone on public streets (which appears to be the case). At the same time, I think the legality of the monitoring has to be justified under Knotts as limited by Karo rather than under the broader third party doctrine cases like Smith v. Maryland that the Sixth Circuit at times invoked in support of its opinion.

For more, here’s the government’s appellate brief in Skinner; here are the defense opening briefs and reply brief.