Happy Birthday, Lysander.

Peter Eyre of Bureaucrash reminds us that today is the birthday of Lysander Spooner, abolitionist, lawyer, entrepreneur, and radical libertarian theorist.

It is worth noting that Spooner's No Treason: The Constitution of No Authority was written well after his book on slavery. In the later work, he applied a contract model of actual consent to the Constitution and found its authority wanting. In the earlier work, he employed a hypothetical contract model to the Constitution to show why it should be construed to protect the background rights of the people--among whom included persons held in bondage as slaves. He did not claim that hypothetical consent was the same as actual consent. Instead, he argued that because the consent claimed for the constitution was "theoretical" only, and based on presumed consent and not actual expressed consent, it could not be presumed that anyone consented to a document that violated their natural rights--and the Constitution should not be so construed unless its original meaning was irresistibly clear.

For those who implicitly accept the view articulated in Dred Scott that slaves could not be included in "the People," consider this. One of the clauses of the original Constitution that is taken as referring to slaves describes them in the following way "No person held to service or labor in one state, under the laws thereof." The Fifth Amendment includes the following: "nor shall any person . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." As was noted by abolitionist William Goodell, the pro-slavery reading of the Constitution would have the word "person" mean two different things in the same Constitution. At minimum, this undercuts the Supreme Court's decision in Prigg v. Pennsylvania that the Fugitive Slave Act--which clearly denied due process to persons who were claimed to be runaway slaves while residing in a free state--was constitutional. If you read Spooner, Goodell, and others you find the case for the constitutionality of slavery, and all the powers then claimed to protect it, to be remarkable shakey.

While some modern scholars who have discussed Spooner have belittled him as a marginal, it appears that his abolitionist writings were taken quite seriously during his lifetime. Not only did Douglass credit Spooner (and others) with his conversion from the position advocated by William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips that the Constitution was "a covenant with death and agreement with hell," but Phillips himself was prodded by the reception of Spooner's initial work to self-publish a 90 page reply. Indeed, Spooner's original monograph was 145 pages, and he added another 145 pages in response to Phillips. I have also found that Spooner's arguments were cited in Congress.

In his classic 1951 book, Equal Under Law, Jacobus tenBroek credits Spooner's writings for contributing to the theory of citizenship that led to the first sentence of the Fourteenth Amendment defining citizens as any person born in the United States.

You can find most of Spooner's writing and surviving correspondence at LysanderSpooner.org, and more at Rodrick Long's Molinary Institute. A short article of mine on Spooner's original meaning approach to constitutional interpretation is here. It was after reading Spooner's The Unconstitutionality of Slavery that I eventually became an originalist.

So Happy Birthday Lysander. You are well remembered.

On this day 201 years ago Lysander Spooner was born on in central Massachusetts. Like de Molinari a century before, Spooner's ideas were extreme. And though "extreme" usually has negative connotations, recall what Barry Goldwater's speechwriter, Karl Hess, penned almost 50 years ago: "Extremism in defense of liberty is no vice."Spooner's influential book, The Unconstitutionality of Slavery, changed Frederick Douglass's mind about the constitutionality of slavery. In this regard, it is a nice coincidence that this year Spooner's birthday falls on Martin Luther King Day.

Spooner, one of the most outspoken abolitionists of his day, advocated for the immediate end to slavery and wrote that the U.S. Constitution was no different than any other contract and thus binding only to those who signed it. A lawyer by training, he ignored related occupational licensing laws and later directly challenged the postal monopoly. Without question he remains a source of inspiration for freedom-fighters today - whether their medium be academia or activism.

It is worth noting that Spooner's No Treason: The Constitution of No Authority was written well after his book on slavery. In the later work, he applied a contract model of actual consent to the Constitution and found its authority wanting. In the earlier work, he employed a hypothetical contract model to the Constitution to show why it should be construed to protect the background rights of the people--among whom included persons held in bondage as slaves. He did not claim that hypothetical consent was the same as actual consent. Instead, he argued that because the consent claimed for the constitution was "theoretical" only, and based on presumed consent and not actual expressed consent, it could not be presumed that anyone consented to a document that violated their natural rights--and the Constitution should not be so construed unless its original meaning was irresistibly clear.

For those who implicitly accept the view articulated in Dred Scott that slaves could not be included in "the People," consider this. One of the clauses of the original Constitution that is taken as referring to slaves describes them in the following way "No person held to service or labor in one state, under the laws thereof." The Fifth Amendment includes the following: "nor shall any person . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." As was noted by abolitionist William Goodell, the pro-slavery reading of the Constitution would have the word "person" mean two different things in the same Constitution. At minimum, this undercuts the Supreme Court's decision in Prigg v. Pennsylvania that the Fugitive Slave Act--which clearly denied due process to persons who were claimed to be runaway slaves while residing in a free state--was constitutional. If you read Spooner, Goodell, and others you find the case for the constitutionality of slavery, and all the powers then claimed to protect it, to be remarkable shakey.

While some modern scholars who have discussed Spooner have belittled him as a marginal, it appears that his abolitionist writings were taken quite seriously during his lifetime. Not only did Douglass credit Spooner (and others) with his conversion from the position advocated by William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips that the Constitution was "a covenant with death and agreement with hell," but Phillips himself was prodded by the reception of Spooner's initial work to self-publish a 90 page reply. Indeed, Spooner's original monograph was 145 pages, and he added another 145 pages in response to Phillips. I have also found that Spooner's arguments were cited in Congress.

In his classic 1951 book, Equal Under Law, Jacobus tenBroek credits Spooner's writings for contributing to the theory of citizenship that led to the first sentence of the Fourteenth Amendment defining citizens as any person born in the United States.

You can find most of Spooner's writing and surviving correspondence at LysanderSpooner.org, and more at Rodrick Long's Molinary Institute. A short article of mine on Spooner's original meaning approach to constitutional interpretation is here. It was after reading Spooner's The Unconstitutionality of Slavery that I eventually became an originalist.

So Happy Birthday Lysander. You are well remembered.

Related Posts (on one page):

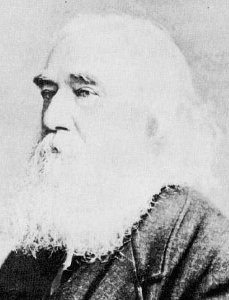

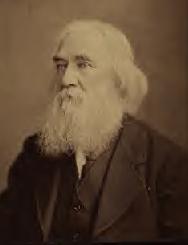

- Two Pictures of Lysander Spooner:

- Happy Birthday, Lysander.