|

|

Alexander "Sasha" Volokh

My tour of medieval Europe

Dover, England, July 2, 1999

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

...

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain.

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

- Matthew Arnold, "Dover Beach," 1867

Above: A picturesque view of Dover Castle.

Jonathan Coad writes: "Dover Castle, one of the mightiest fortresses

in western Europe, guards the English end of the shortest sea

crossing to the Continent.

Its location, overlooking the Straits of Dover, has given it immense

strategic importance and has ensured that it has played a prominent

part in national history.

Its shape was largely determined by a pre-existing Iron Age

hillfort, while within its walls stand a Roman lighthouse and an

Anglo-Saxon church, the latter probably once forming part of an

Anglo-Saxon burgh or fortified town.

"There has been a castle here since November 1066.

That month, Duke William of Normandy's forces, fresh from victory at

the Battle of Hastings, constructed the first earthwork castle

before continuing their march on London.

The castle was to retain a garrison until October 1958 -- an

892-year span equalled only by the Tower of London and Windsor

Castle.

"During its medieval heyday this was very much a frontier fortress,

looking across to the frequently hostile lands of the counts of

Flanders and the kings of France.

Under Henry II the castle was rebuilt, incorporating concentric

defences and regularly spaced wall towers, a combination then

without parallel in western Europe.

In 1216 it successfully withstood a prolonged siege.

By the 1250s its medieval defences had assumed the extent and shape

which they retain to this day and the castle, on its cliff-top site,

formed a highly visible symbol of English royal power.

"After declining in importance from the sixteenth century, the

castle was modernised and its defences extended in the 1750s and

again during the Napoleonic Wars.

Further alterations and additional gun batteries added in the 1870s

enabled the castle to retain the role of First-Class Fortress almost

until the end of the nineteenth century.

"During both world wars the castle was rearmed, but perhaps its

finest hour came in May 1940.

In that month Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay, in naval headquarters

deep in the cliff, organised and directed the successful evacuation

of the British army from Dunkirk.

These same tunnels became in the 1960s a Regional Seat of Government

in the event of nuclear war; only in 1984 were they finally

abandoned."

Further quotes are from Dover Castle, the English Heritage

guidebook.

Above: Roman lighthouse and Saxon church

"At the highest point in the castle stand two buildings which

predate the castle -- the remains of a Roman lighthouse and a Saxon

church.

The surrounding bank dates from the thirteenth century but underlies

one dated by archaeologists to the mid-eleventh century, suggesting

that this area could be the site of the first small castle built by

William the Conqueror.

"In the second half of the first century AD the Romans began to

develop Dover as a port.

To guide ships across the Channel they constructed three

lighthouses.

One, the Tour d'Odre, stood at Boulogne; the other two were at

Dover, on high ground on either side of the small harbour.

The foundations of the western lighthouse can be seen at Drop

Redoubt on Western Heights on the far side of the town, while the

eastern one still stands within the later castle, where it forms one

of the most remarkable surviving structures of Roman Britain.

"The Roman pharos or lighthouse was originally an octagonal

tower with eight stepped stages, of which only four survive.

It rose to a height of some 24 m (80 ft).

Within its rectangular interior were a series of timber floors; at

the top there was probably a platform for some form of brazier.

After its abandonment by the Romans the tower became ruinous.

Later its exterior was refaced, and between 1415 and 1437 the top

was rebuilt as a bell-tower for the neighbouring church by Humphrey,

Duke of Gloucester.

"Adjacent to the lighthouse stands the church of St Mary-in-Castro.

Despite heavy restoration in the nineteenth century, it remains the

finest late Saxon building in Kent, dating from around AD 1000.

Its location, and the evidence of numerous Saxon burials found in a

graveyard to its south, suggest that there was a pre-Conquest

civilian settlement here.

The church probably originally formed part of an Anglo-Saxon

burgh, a fortified town within the Iron Age ramparts.

The builders made extensive use of Roman tiles and the church

retains its Saxon cruciform (cross-shaped) plan.

Certain details in the interior, such as the vaults in the chancel

and over the crossing, and the chancel windows, show that the church

was modified in around 1200, probably by the same masons who had

worked on the chapels in the keep.

"By the early eighteenth century the church was in ruins.

During the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15) it was used as a Fives Court

and then as the garrison coal store.

In 1862 it was restored by the architect Sir George Gilbert Scott

and in 1888 William Butterfield completed the tower and added the

unsympathetic mosaic decoration to the nave.

The nearby church hall forms part of this mid-Victorian renaissance

of this part of the castle; initially it was the schoolroom for the

children of the garrison.

"The surrounding medieval bank provides fine views.

It was once topped by a medieval curtain wall linking to the eastern

outer defences near Pencester's Tower and running westwards to

Peverell's Tower via Colton's Gateway.

The wall was demolished in 1772 but Colton's Gateway, built by King

John, and the length of curtain wall beyond it, give an impression

of the height of the missing sections.

Beside the church hall are the earthworks of Four-Gun Battery,

constructed in 1756."

Above: Henry II's keep

"In the 1170s and 1180s, Henry II's military engineer Maurice was to

transform Dover.

Central to the great rebuilding was the massive new keep, which

ultimately was to be surrounded by a double ring of defensive walls,

making Dover the first concentric medieval fortification in western

Europe.

The keep itself served multiple functions as a great storeroom,

occasional residence of the monarch and his court, and ultimate

stronghold during a siege.

With few intervals and modifications, it was to retain a varied

military role up to 1945.

"The first line of defence beyond the keep were the curtain walls

and towers of the inner bailey, with its two strongly defended

gateways.

Within the courtyard a succession of buildings was later added for

royal and garrison use.

Today the inner bailey is lined with barracks constructed in the

mid-eighteenth century, but many of these incorporate the remains of

earlier medieval structures."

Above: Hubert de Burgh, in a Victorian painted window at

Dover Town Hall

"Hubert de Burgh was an able and efficient administrator and a

courageous soldier who had a long and distinguished career serving

Kings Richard I, John and Henry III.

In 1204 he gained fame through his prolonged defence of Chinon

Castle during John's retreat from Normandy, an experience that

undoubtedly helped him during the great siege of Dover in 1216-17.

In 1215 he was appointed Justiciar (chief minister) to the king, but

in the 1230s powerful opposition, and loss of the king's support,

led to his sudden downfall.

He died in 1243."

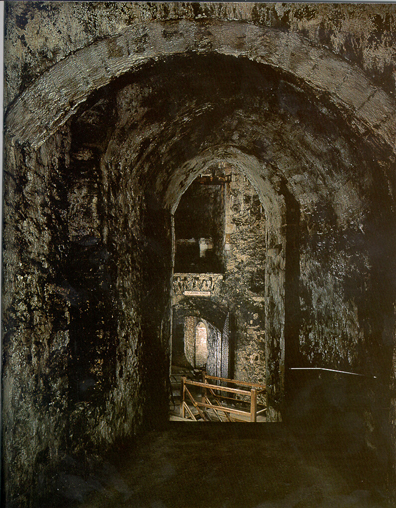

Above: The medieval tunnels

"The medieval underground tunnels at the northern tip of the castle

form part of an extraordinary defensive system constructed by Hubert

de Burgh after the siege of 1216.

His was the first of several attempts to strengthen this area of the

castle.

Hubert's new defences were substantially modified in the eighteenth

century, but the core of his underground work remains.

The tunnels were designed to provide a protected line of

communication for the soldiers manning the northern outworks, and to

allow the garrison to gather unseen before launching a surprise

sortie.

Later, during the Napoleonic Wars, the tunnels were largely

remodelled along with the outer defences, and were further

modernised in the 1850s.

In their date and complexity these tunnels are unique.

Access to them is down a spiral stair beneath the bridge leading

north from King's Gate barbican."

Above: The battlements walk

"Henry II's rebuilding campaign, begun in the 1180s and completed by

his successors Kings John and Henry III, made Dover Castle one of

the most powerful of all medieval castles.

This great strength was due to the successive layers or rings of

defensive walls protecting the keep in the centre.

This is the earliest use of such concentric defences on a castle in

western Europe.

These fortifications were to be augmented by artillery outworks in

the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, most notably during the

1790s when attack by France was widely expected.

The Battlements Walk follows the outer line of the medieval

fortifications and gives stunning views over the castle's defences

and surrounding areas."

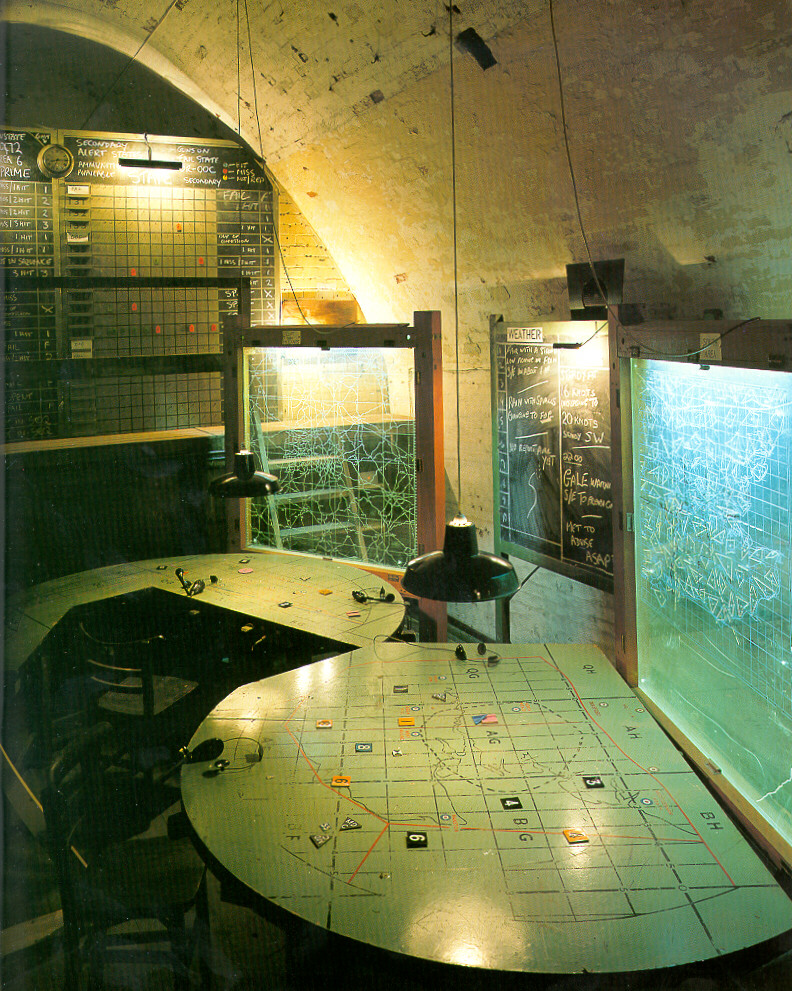

Above: (No longer) Secret Wartime Tunnels.

"The Secret Wartime Tunnels are a complex web of underground

rooms and passages which played a key role during the Second World

War.

They were later adapted to form the headquarters of one of a number

of Regional Seats of Government, secure accommodation to be used in

the event of a nuclear attack on Great Britain.

However, the first tunnels here are considerably older and were

built for a very different purpose [defense against France in the

late 18th century]....

"The three main headquarters within the tunnels at the outbreak of

the Second World War were the naval headquarters for the Dover

Command, the Coastal Artillery operations room and the anti-aircraft

operations room.

This last has been partly reassembled, again making use of

contemporary equipment.

"By contrast, Admiral Ramsey's former naval headquarters today

stands empty, enabling visitors to appreciate the huge scale of the

Georgian underground barracks.

In the walls are fireplaces which once provided some warmth for

George III's troops quartered here, while lines on the walls and on

the timber floor installed in the late 1930s show where naval office

partitions were located.

During the war years this tunnel was a warren of offices, with the

Admiral's own quarters in the cliff front overlooking Dover Harbour

and the Straights.

(The cliff end was sealed by the Home Office in the 1960s.)

Although it is silent now, little effort of imagination is needed to

visualise this once-busy hub of naval activity, scene of so many

momentous decisions.

"The hospital tunnels, known as Annexe Level, lie above and slightly

to the rear of the Casemate Level tunnels.

The main entrance links directly to an ambulance lay-by on the road

running up from Canon's Gateway.

Inside, the differences in plan, scale and construction between the

two sets of tunnels are at once apparent.

The main tunnels of the 1790s are lofty, spacious chambers, lined

with brick.

Their 1941 equivalents are far more cramped and are lined with steel

shuttering.

In addition the hospital tunnels, unlike their Georgian

predecessors, are laid out on a regular grid pattern.

"The hospital comprised a carefully planned sequence of reception

areas, wards, washrooms and latrines, galley and food store, and

operating theatres.

Most of the equipment on display is contemporary.

The operating theatre, galley and mess are based on photographs

showing them in use towards the end of the Second World War.

Casualties mercifully were far lower than anticipated and, as a

result, some of the tunnel wards were later given over to

dormitories and mess accommodation for military personnel based at

the castle."

Back to Hastings/Battle

Advance to London

Return to places page

Return to home page

|