|

|

Alexander "Sasha" Volokh

My tour of medieval Europe

London, England, July 3-6, 1999

Above:

The best McDonald's food is the vegetable (pronounced in four syllables)

samosa, now sadly discontinued. The Lamb McSpicy sandwich is interesting

but a bit on the flavorless side. This picture was taken at Heathrow at

the beginning of the trip.

Above:

This is a man with a guitar who boarded the Underground train from Heathrow into London. He

tried to

play "Bad Moon Rising" and have us all sing along. However, no one knew the words or was willing to

share.

Above:

A gaggle of Spanish girls were sitting across from me in the Underground train, all carrying bags that

looked like this one. "don't" is apparently the name of, of all things, a Spanish organization that

teaches Spanish kids English. I didn't have the heart to tell them that "don't" is also an adjective

you kids use these days, meaning, roughly, "uncool."

Above: Mungo and Emily Wilson, authentic medieval

Englishpeople.

Above:

An interesting ad, in the Underground train, for car insurance,

targeted at women. Note also the phone number.

Above: Friend of the family's, Princess Jean Galitzine.

Above: The Orpington Sundial.

What is this? To come.

Above: Font in the church at Orpington.

Above: Oxymoron of the day, seen in Orpington, commuter

suburb of London.

Above: English laundry detergents.

My translation of Adam McNaughton's Macbeth song

says, "Get me Tide or Biz or Cheer and I'll get out that damned

spot," but the original speaks of "Persil, Ariel, Daz, and Flash."

Above: Christina and Keith Fraser.

Above: Santa and his reindeer on the streets of London in

July.

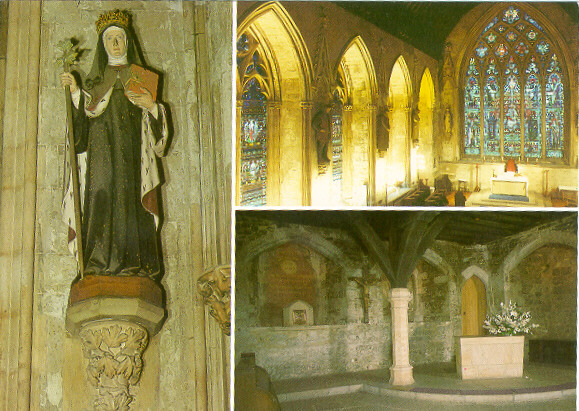

Above: Church of St. Etheldreda.

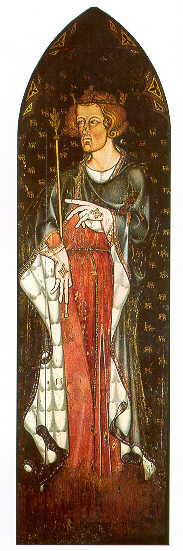

Left: St. Etheldreda, c. 630-679, foundress of Ely Cathedral.

Above right: upper church with east window.

Above left: the crypt, built c. 1251.

The medieval chapel (perhaps the Bishop of Ely's

private chapel) with the crypt (perhaps for the local residents) is

all that is left of the palace of the bishops of Ely.

Except for Westminster Abbey, St. Etheldreda's is the only surviving

work of the reign of Edward I (1239-1307) in London.

Tradition has it that Henry VIII first met Cranmer, Reformation-era

Archbishop of Canterbury, in St. Etheldreda's.

Queen Elizabeth I forced the bishop to give the property over to the

Crown.

In the early 17th century St. Etheldreda's was used as the Spanish

Embassy.

In 1624 the chapel "reverted to the Protestant cult."

The church was "mercifully spared" from the Great Fire by a change

of wind, and the crypt was used as a brewery.

The church was "reclaimed for the faith" in 1879.

"In one sense . . . St. Etheldreda's . . . belongs to everyone in

our land, especially those who come from East Anglia where St.

Etheldreda lived and died in great holiness in A.D. 678."

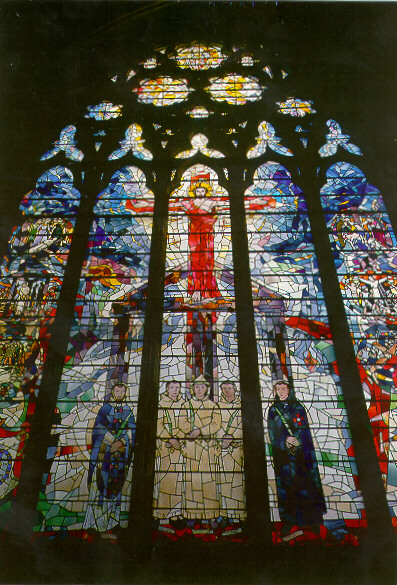

Above: St. Etheldreda's, Ely Place, Holborn Circus.

A view of Upper Church and East Window.

Above: St. Etheldreda's, Ely Place, Holborn Circus.

West window in the Upper Church, dedicated to the English Martyrs.

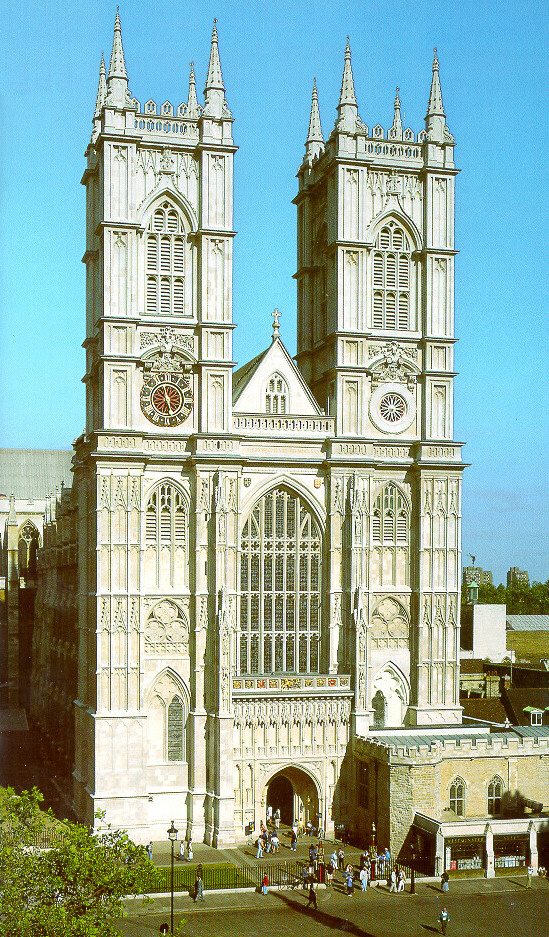

Below: Pictures from Westminster Abbey.

Quotes are from Westminster Abbey, the Pitkin guidebook.

Above: Westminster Abbey.

"Legend has it that a church was first founded on the site of Westminster

Abbey by Sebert, king of the East Saxons (died AD 616) at the instigation

of Mellitus, the first Bishop of London.

The first religious foundation that we can be sure of was that of St.

Dunstan, a later Bishop.

In the 960s, on an island in the Thames, he set up a Benedictine abbey.

Very little is known about the building except that it stood not far from

where the west door is now.

Before long it was succeeded by a great monastery created by King Edward

the Confessor (1042-66) on an adjacent site.

Its focal point was a church, dedicated to St. Peter, similar in area to

the present building and built in the Norman French (Romanesque) style.

The new church was hurriedly consecrated in late December 1065, just a few

days before King Edward died.

His remains still rest in the chapel which bears his name at the east end

of the abbey.

"The king built a palace nearby, in this one plan cementing bonds between

Church and State which still continue.

From the 14th to the 16th centuries, parliaments met in both the Chapter

House and the refectory of the abbey.

During this same period were buried most of the kings and queens whose

tombs we see in the abbey today.

"Less than 200 years after the first abbey's completion Henry III, in

keeping with the religious zeal of the times, determined to replace it

with something on a much grander scale.

The old abbey was progressively demolished and replaced from the east end.

Nothing of the old church now remains.

Only in parts of the monastic buildings around the cloister does any

Norman work still survive.

The new abbey, although of similar area, was to be taller, lighter and

more spacious -- using better stone, mainly a greenish-grey sandstone from

Reigate 37 kilometres (23 miles) away, with limestone from Caen in

Normandy and pillars of polished Purbeck stone from Dorset.

The master mason -- architect in today's terms -- was Henry de Reyns.

"The style of the new Gothic church owed much to the style of contemporary

French cathedrals -- the apse with its radiating chapels, the tall windows

and wall arcades of those chapels, the rose windows and wonderful flying

buttresses.

The outstanding French feature is the soaring height of the roog (23 m/103

ft) in relation to the narrow width of the nave and chancel (11 m/35 ft).

However, the long nave and broad transepts are thoroughly English, as are

the elaborate mouldings of the arches, the sculptured decoration and the

use of polished Purbeck stone.

"By the time of King Henry's death in 1272 the quire, sanctuary, transepts

and some bays of the nave were complete, grafted incongruously onto the

lower Norman nave.

This state of affairs lasted for over a century, for there was no more

money.

Even to reach this stage, Henry had been forced to reclaim and pawn jewels

that he had donated to adorn Edward the Confessor's shrine!

"Many years of laborious but erratic progress followed as work on the nave

continued westward.

It is important to remember that the abbey we see today is not as medieval

pilgrims to the Confessor's shrine would have seen it.

They would have been confronted by exuberant colour everywhere -- walls

and vaulting covered with pictures and patterns in vibrant red, blue and

gold.

Tombs were encrusted with jewels and adorned with precious relics.

"The nave was completed in 1517, the year that Martin Luther first lit the

fires of Reformation.

In 1540 the Abbot of Westminster surrendered his monastery to be

dissolved.

The Confessor's shrine was torn down and despoiled, statues destroyed and

any forms of adornment abandoned.

From 1540 to 1550 the abbey became a cathedral in a newly created diocese

of Westminster.

The accession of Mary I in 1556 saw a community of monks re-established.

Its brief existence was terminated in 1560 when Elizabeth I's Royal

Charter designated the abbey as a collegiate church with a dean and a

chapter of 12 canons.

The building was destined to retain its unfinished look for a further 200

years.

Only in 1745 was the building as we know it today completed when the

western towers were finished to the design of Sir Christopher Wren."

Above: Westminster Abbey, the nave from the west door.

Note "the very French proportions of a 3:1 ratio of height to width."

The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior is surrounded in red poppies in the

foreground; St. George's Chapel (Warrior's Chapel) in the background.

Above: Westminster Abbey; a panel from the sedilia, erected in the time

of Edward I (reigned 1272-1307).

Possible a picture of Edward I himself.

Above: Westminster Abbey; the tomb of Edward the Confessor (1269).

The tomb was "once a visual feast of gold and gilt encrusted with jewwels

and mosaic.

Since 1540, only the base remains of the original.

The recesses are where pilgrims knelt to pray."

"St. Edward's Chapel is by tradition the focus of the abbey, for it

contains what was once its greatest wonder, the tomb of the founder, King

(later Saint) Edward the Confessor.

Edward, who ruled 1042-66, was famed for his asceticism and piety.

He was originally buried by the altar of the 11th-century church but,

after miracles took place there, William I commissioned a fine tomb,

gilded and jewelled.

This became an object of national reverence and pilgrimage.

"Henry III in his reconstruction of the abbey had an even more impressive

tomb constructed.

A golden shrine (feretory) containing the Confessor's coffin was placed on

a base of Purbeck 'marble' and mosaic, surrounded by a pavement of Italian

porphyries.

Above was a movable canopy.

The feretory was decorated with gold images of kings and saints.

Two gilded statutes, of St. Edward and St. John the Evangelist, stood on

pillars at the side, and an altar was erected at the west end of the

chapel.

On 13 October 1269, Henry III, his brother and two sons carried St.

Edward's coffin in procession to its new resting place.

"In 1540 the monastic community, which had been at Westminster for nearly

600 years, was dissolved by order of King Henry VIII.

The shrine, as were so many others throughout the land, was robbed of its

relics and seriously damaged.

The body in its coffin was removed and buried elsewhere.

In 1557. under Henry's daughter Mary I, the shrine was rebuilt rather

clumsily.

The jewels were replaced and, as there was no feretory, the coffin was

restored to the top part of the stone base.

The next 100 years saw several acts of vandalism and theft.

In 1685 after King James II's coronation, a choirman, Charles Taylour,

removed a gold cross and chain having seen it glint through a hole in the

coffin.

Having handed it in, he received 50 pounds from the king for his

initiative and honesty.

After that, a surrounding coffin was constructed and fastened with iron

bands.

Since then the body has rested undisturbed."

Above: Westminster Abbey, the Chapter House.

"Some of the glass dates from Sir George Gilbert Scott's restoration

1866-72, which revealed medieval encaustic floor tiles in excellent

condition.

On the walls are early 15th-century paintings, including a scene of the

Last Judgement."

"The Chapter House was where monastic business was conducted, important

guests received and often, in early times, where superiors were buried.

The chapter, the monks' daily conference, took place there.

After Mass, the monks processed to the Chapter House.

There they prayed for the dead and for their benefactors.

A monk would read aloud a chapter of the Benedictine Rule, which is how

the meeting got its name.

The abbot or his delegate often then gave a sermon or commentary.

The day's business followed -- notices, correspondence, duties, reports,

etc.

There might then be a choir practice or rehearsal particularly if an

important service was imminent.

Finally monastic discipline was discussed.

Any breaches of the Rule were brought to light and a superior would decree

punishment.

Often the offending monk was beaten with a rod or bundle of sticks.

The Rule dictated t hat during this 'all the brethren should bow down with

a kind and brotherly compassion.'

"Westminster's Chapter House is the second largest in England (after

Lincoln), reflecting its national importance, for from its completion in

1253 until 1547 it was one of the regular meeting places of Parliament.

Since the Reformation the Chapter House has belonged to the Crown, not the

abbey.

It only survived the ravages of dissolution because it was used to house

royal records, which it did until 1863.

During its three centuries as a store it suffered ravages of a different

kind: the windows were blocked, an internal gallery built and -- final

insult -- in 1744 the vault was destroyed and a new floor inserted,

resting on the central pillar.

Sir George Gilbert Scott between 1866 and 1872 returned some parts to

their original appearance but other details, such as the steep roof, owed

more to his own fancy than to medieval reality."

Above: Westminster Abbey, Poet's Corner -- Shakespeare

Above: A cute travel insurance ad on the Underground!

Back to Dover

Return to places page

Return to home page

|