The site might be down much of the weekend. By Monday, we should be on WordPress, hosted by Hosting Matters, with design by Sekimori. (Many thanks to Sekimori, by the way, for all her help with the conversion so far, and for her help to come!)

Saturday, September 26, 2009

Houston-based Vinson & Elkins is the latest big law firm to beef up its D.C. appellate practice by hiring a former Supreme Court law clerk and respected alum of the solicitor general's office. An announcement is due soon that it has hired John Elwood, an eight-year veteran of the Bush Administration Justice Department, to start on Monday as a partner in the D.C. office.

Elwood, 42, clerked for Justice Anthony Kennedy in the 1996-1997 term. After working at Miller, Cassidy, Larroca & Lewin and then Baker Botts, he joined the Justice Department's criminal division in 2001, moving to the SG's office in 2002. After arguing five cases before the high court, he moved to the Office of Legal Counsel, and by the time he left on Inauguration Day in 2009, he was the senior deputy in that office.

Friday, September 25, 2009

It is also worth noting that just ten days ago, the Ninth Circuit rejected the line of cases that the government relied on in the Lori Drew prosecution in a civil case, LVRC Holdings v. Brekka. This is particularly interesting because in Drew, Judge Wu accepted the government's broad reading of the statute as a matter of statutory interpretation; he only dismissed the case because of the constitutional vagueness problem. Under Brekka, however, the Ninth Circuit seems to have rejected the Government's very broad reading of the statute as a matter of statutory interpretation.

In any event, if the Government does in fact appeal the Drew case, I plan to work on the appeal.

Thanks to a helpful reader, I've now located a copy of the CRS report on recent events in Honduras I mentioned here. The report, which was actually prepared by a different part of the Library of Congress and not CRS, the Law Library of Congress, the division of the Library of Congress responsible for reports on foreign law, is available here.

Related Posts (on one page):

- "CRS Report" on Honduras "Coup":

- CRS on the Honduras "Coup":

On Wednesday, I wrote a brief post on ACORN's lawsuit against those who made and distributed the now-infamous undercover videotapes of ACORN staff. In the post, I linked to a Washington Post story on the suit. Today, however, I learned that the story at that link is no longer the same as when I made my initial Wednesday post. As noted in an early comment on my post, the original story included the following:

In an exclusive interview with the Post, founder Wade Rathke said conservative claims that ACORN, the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, is a "criminal enterprise" that misuses federal and donor funds for political ends -- a claim contained in a report by House Republicans -- are a "complete fabrication." He said exaggeration and conjecture about the group are being passed off daily on cable television and web-site blogs as documented fact.Portions from this passage no longer appear in the story as it now appears on the Post website. Now the relevant portion of the story simply reads:"It's balderdash on top of poppycock," said Rathke, who was forced out last year amid an embezzlement scandal involving his brother.

Meanwhile, the departed founder of ACORN said many of the accusations about the group are distortions meant to undermine President Obama and other Democrats.Missing are the reference to the "embezzlement scandal" or the colorful quote. Gone as well is the mention of an "exclusive" interview. Yet there is no acknowledgment anywhere in the story that it was edited.In an interview, Rathke said conservative claims that ACORN is a "criminal enterprise" that misuses federal and donor funds for political ends -- an allegation contained in a report by House Republicans -- are a "complete fabrication." He said exaggeration and conjecture about the group are being passed off daily on cable television and blogs as documented fact.

So, the Washington Post published a story on its website, revised the story to omit details that appeared in the relevant piece, and yet did not disclose these facts to the Post's online readers. Isn't this a problem? There may well have been valid reasons for revising the story. Perhaps an editor thought the story got relevant facts wrong or concluded reference to the embezzlement scandal was unfair. Whatever the reason for the change, the Post should have disclosed that changes were made and that it had decided to excise information included in the original story.

This is not the first time I've noticed the web site of a prominent news organization failing to disclose that it had edited the web-based version of a story after initial publication. The NYT, for example, did it when reporting on the Administration's decision to abandon a planned missile defense of Poland and the Czech Republic, as I noted in an update to this post. Is this now common practice? If so, it seems to be a major failing. Responsible bloggers routinely disclose anything more than the most minor stylistic and typographical revisions to published posts. I would think newspaper websites could do the same. Indeed, shouldn't newspapers at least match the disclosure norms observed by bloggers? After all, they're the real journalists.

Some commenters said they were surprised that I've posted several times about the Obama praise song issue; they suggested that the matter is minor enough not to merit three posts (or, I suppose, now four, depending on how you count this one).

How many article a newspaper publishes about a particular incident may well reflect the importance of the incident. But bloggers operate differently. Among other things, (1) bloggers are more likely to post about amusing things they found in the course of researching the story, (2) bloggers are more likely to post follow-up factual updates, even relatively minor ones, (3) bloggers are more likely to criticize other responses to the story (whether from the media or from others), (4) bloggers are more likely to use the story as a launching off point for a discussion about other matters, such as blogging practices and the difference between blogs and the media, and (5) bloggers are more likely to react to reader comments, either to respond to them or to post something that the comment highlights as interesting.

This is what happened here. I posted the original story this morning, chiefly because I saw some academic friends of mine comment on it on a discussion list that I'm on. That was post 1. I then decided to do a bit more searching, to see how other media outlets were covering this; a news.google.com search for "Bernice Young" pointed me to the Media Matters post, which struck me as having a laughably over-the-top headline. A newspaper reporter likely wouldn't have written another story just about that, but I thought it was amusing and worth noting. I then saw that the substantive defense in the Media Matter post item was quite weak as well, so I included that in the post. That was post 2. The news.google.com query also showed me that there was a follow-up factual story in the news about the principal's response; a commenter to the original post also quoted from it, so that led me to conclude that this was a useful factual update. That was post 3. And the comments to post 3 led me to step back and remark on the difference between multiple blog posts and multiple articles in the newspaper, hence this post 4.

Now this is surely not one of the great stories of our time -- not even close. But my point is that the presence of multiple blog posts, unlike the presence of multiple articles in the same newspaper, need not be closely related to the importance of the story.

Related Posts (on one page):

where young students were videotaped singing the praises of President Obama is making no apologies for the videotape and says she would allow the performance again if she could, according to [three] parents who spoke with her Thursday night....

Parent Jim Angelillo said [Principal Denise] King told him the lesson was merely part of Black History month, and not an attempt to indoctrinate students, as critics have charged....

King has long been a fan of Obama, hanging pictures of the president in her school's hallways and touting her trip to his inauguration in the school yearbook.

Included in the full-page yearbook spread were Obama campaign slogans ("Yes we can! Yes we did!") and photos King took in Washington on Jan. 20, when she attended the inauguration.

There also were photos taken at the school depicting students doing Obama-themed activities about their "hopes for the future," featuring posters of Obama....

Attempts to reach King on Friday were unsuccessful....

I should stress that one should always be cautious about second-hand accounts of oral conversations; it may be that the parents misunderstood the principal, or that important context was omitted. That's why I hope that the principal, who is after all a public servant, does indeed publicly explain her position herself.

Related Posts (on one page):

Is it just me, or is that headline just a bit rhetorically over the top? (No, the last link doesn't make a moral analogy, just an analogy in the rhetoric.) "New low"; "right-wing media minions" (why not "nattering nabobs of negativism"?); "fearmongering" -- just a bit much for a credible debunking, it seems to me.

This is especially so when part of the fearmongering that is supposedly debunked is actually not bunk at all; here's the response the site (Media Matters) gives as to the Obama praise song incident:

Conservative media fearmonger about unauthorized YouTube video of school kids "praising" Obama

The Drudge Report: "SHOCK VIDEO: School kids taught to praise Obama ..." On September 23, Internet gossip Matt Drudge linked to a YouTube video purportedly showing "[s]chool kids taught to praise Obama." The video, showing young schoolchildren in New Jersey singing a song about Obama, provides no evidence that the children or their parents consented to having the video posted on YouTube.

America's Newsroom: "Many parents ... just don't want this sort of political cheerleading, if you will, in the classroom." On Fox News' America's Newsroom, hosts Bill Hemmer and Megyn Kelly aired the video and asserted that "many parents" don't want kids "singing praises" to Obama. Before showing the video, Hemmer said: "It is one thing to have kids say the Pledge of Allegiance, but we're not sure what's going on with the videotape now online when students are singing praises to the president and why some parents are saying, not with my kid." Later, Kelly teased the video by saying, it's "getting attention on The Drudge Report website this morning. It shows young children singing the praises, quite literally, of the president." She continued:

KELLY: Well, information posted with the clip says that it is from the Bernice Young School in Burlington Township, New Jersey, but the school won't exactly confirm that for us. In fact, they won't confirm anything for us. We have made multiple attempts to ask them about these students, about this tape and how this came about. We are hoping that they can get back to us shortly, so that we can clear this up.

Already we're getting a lot of emails from our viewers. It went on from there -- you saw a clip of the children singing. Then came a bit of a chant by the children where they praised President Obama for all his great accomplishments, saying, quote, "You're number one. Hooray, Mr. President, we're really proud of you." And on and on it goes.

You know, many would have no problem with this. Many parents would, and just don't want this sort of political cheerleading, if you will, in the classroom. We just don't know the details behind the tape, but it certainly caught our attention and we're trying to find out from, again, from this school, which we have multiple calls into. The B. Bernice Young Elementary School, Bernice Young Elementary School in Burlington, New Jersey. And as soon as we have it, you'll have it. [America's Newsroom, 9/24/09]

The Fox Nation: "School Children Sing Songs of Obama's Glory." On September 25, the allegedly fair and balanced TheFoxNation.com posted the video with the headline "School Children Sing Songs of Obama's Glory." fearmongerkids2

Beck: Song sounds like "a hymnal for a dictator." On the September 24 edition of his radio show, Beck said: "I want to show you, and tonight I'm going to play the tape for you, of indoctrination that is going on. We've been going through all of this indoctrination for the last few days. Tomorrow, I do a full hour live with moms, and their children, and we're going to talk a little bit about things they're concerned with -- and indoctrination I know will come up. Play this, this is -- do we know where this is from? Elementary School in Burlington, New Jersey. The B. Bernice Young Elementary School. The woman who did this is, I believe, an activist, she's the principal, or the teacher. I don't have her name here. But listen to -- this is -- these are elementary school children, and they are singing a song for Barack Obama." After Beck played audio of the video and read the words out loud, he said it sounded like "a hymnal for a dictator. ... Does anybody see what's going on? Does anybody see what's going on?" Later, Beck said: "This is indoctrination. This should horrify the American people." [Premiere Radio Networks' The Glenn Beck Show, 9/25/09]

Beck also promoted the video September 24 on his Twitter feed: RT @keepthemhonest: How young does Obama target (more indoctrination video) http://is.gd/3C1Qc @glennbeck #tcot

Burlington Township School District superintendent: Song is from Black History Month activity, and the "recording and distribution of the classroom activity was unauthorized." The school board's superintendent wrote in a letter to parents that "[t]he video is of a class of students singing a song about President Obama. The activity took place during Black History Month in 2009, which is recognized each February to honor the contributions of African Americans to our country. Our curriculum studies, honors and recognizes those who serve our country. The recording and distribution of the class activity were unauthorized."

Really, that's it for the site's explanation for why this story is supposedly "fearmongering": The event took place during Black History Month; it "honors and recognizes those who serve our country"; and the video was "unauthorized" (note that the "unauthorized" meme makes its way even into the section header). Move along, folks, nothing to see here, nothing to fear, just regular honoring and recognition of public servants, plus the video of the event was unauthorized, which is somehow very important.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Some Thoughts on Multiple Blog Posts:

- "The Principal of a New Jersey Elementary School "

- "New Low: Beck and Right-Wing Media Minions Fearmongering About Kids to Attack Progressives":

- "School Children Singing the Praises of President Obama" (Apparently as a Public School Class Project):

For those unfamiliar with the rule, federal court precedent says that if a federal criminal statute makes it a crime to do "A, B, or C," the indictment should allege that the defendant did "A, B, and C." That is, the prosecutor should switch the "or" to "and", replacing the disjunctive with the conjunctive. Why do that? The cases say that the reason is to avoid uncertainty: If the indictment uses "or," then the defendant has no notice of what the government is charging. If the indictment uses "and," then there is no uncertainty. But here's the trick: The government only needs to prove one of the theories at trial, and the conviction will be upheld on appeal so long as only one of the theories has been proved.

It doesn't take a rocket scientist to see this rule is foolish. Mechanically turning "or" to "and" doesn't actually provide any additional notice. And judges have been noting that this rule is nonsensical for a long, long time. Way back in 1757, Lord Mansfield attacked the rule as useless:

Upon indictments, it has been so determined, that an alternative charge is not good, as ‘forged or caused to be forged’; though only one need be proved, if laid conjunctively, as ‘forged and caused to be forged.’ But I do not see the reason of it; the substance is exactly the same; the defendant must come prepared against both. And it makes no difference to him in any respect.Rex v. Middlehurst, 1 Burr. 399, 98 English Reports 369 (1757). As another court wrote in 1945:

The difference between disjunctive and conjunctive pleading is mostly the difference between tweedledum and tweedledee, and modern jurisprudence, which appraises substance and not form as its essence, accords to such useless learning only a nodding acquaintance. What earthly difference is there between ‘or’ and ‘and’ in a count when the end result is that defendant in both instances must be prepared to meet both or all charges?Commonwealth v. Schuler, 43 A.2d 646 (Pa. Super. 1945).

The obvious question is, how did this rule come about? I spent some time trying to hunt this down in the summer of 2008, together with the help of a research assistant, Sai Jahann, and we were never able to come up with a firm answer. The rule had already been established by the time of the early authorities in English, and neither Sai nor I knew the Latin or Law French needed to read the earlier decisions that might have first announced or first justified the rule.

As best I could tell from the early English cases, the origins of the rule were in early common law pleading rules in an era of common law crimes. Under those rules, each indictment had to allege a single crime. So an indictment couldn't allege that a defendant had committed murder or larceny or burglary; it had to give actual notice of the crime alleged. But in an era of common law crimes, the precise boundaries of how much notice was required was never entirely clear: If it was a crime to stab, punch, or kick someone, it wasn't entirely clear if that was one offense that could be committed three ways or three different offenses.

Exactly how this led to the modern rule of "indict in the conjunctive, prove in the disjunctive" isn't precisely clear. But I found some early English cases in which a defendant had actually committed the offense in all of possible ways, and prosecutors just charged all of the means conjunctively in the indictment. The indictment thus changed the "or" to "and." This got around any possible pleading objections based on lack of notice, as the notice was very clear. But then you had some cases where the defendant would challenge the evidence as to all of the means; perhaps, if it was a crime to "stab, punch, or kick someone," the government had only proved punching and kicking but not stabbing. Courts responded, sensibly enough, that if the crime could be committed any of the different ways, the government had proved the offense if it had proved any of the different ways.

My sense of what happened is that the warnings about notice turned into a general rule that served no real purpose. To be careful, prosecutors started just routinely changing "or" to "and," satisfying any possible objection as to uncertainty, while knowing that they could always just prove one of the means rather than all of them. This then became the accepted and recommended practice, even though the switch from "or" to "and" was purely a question of form. Strange but true — or at least as true as I was able to discern.

According to Fox News,

The commissioner of New Jersey's Department of Education ordered a review on Friday following the posting of a YouTube video depicting school children singing the praises of President Obama.Video of the students at the Burlington, N.J., school shows them singing songs seemingly overflowing with campaign slogans and praise for "Barack Hussein Obama," repeatedly chanting the president's name and celebrating his accomplishments, including his "great plans" to "make this country's economy No. 1 again."

One song that the children were taught quotes directly from the spiritual "Jesus Loves the Little Children," though Jesus' name is replaced with Obama's: "He said red, yellow, black or white/All are equal in his sight. Barack Hussein Obama."

There were apparently death threats sent to the principal; of course, such threats are crimes, and should be punished. But I would hope that those responsible for the school project are properly disciplined as well; public school classrooms shouldn't be used to sing the praises of any sitting (or recent) political figure, whether Bush or Obama or anyone else.

That's not a constitutional matter — there's no Establishment Clause for political speech, and of course schools do routinely glorify past political figures, whether Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, or what have you. They also rightly express a calm respect for current elected officials; when an official comes to visit, for instance, it's proper for teachers to give the normal praise offered such visitors, and for students to join in.

But that some degree of ideological indoctrination and glorification is inevitable in government-run schools, and is in fact one of the purposes of such schools (which have long been justified as means of assimilating children into American democratic culture), doesn't mean that it's proper to lead children in songs praising the current President or particular aspects of his political agenda ("Hooray, Mr. President we honor your great plans / To make this country's economy number one again!"). I would have thought that this was pretty clear, and it probably is to most teachers in most schools — but not, unfortunately, in this instance.

UPDATE: Incidentally, the 2006 "Congress, Bush and FEMA / People across our land / Together have come to rebuild us and we join them hand-in-hand!" schoolchildren's song to First Lady Laura Bush is pretty bad, too -- not quite the same, even if it was organized as a public school activity (which I suspect would indeed be so), since it didn't involve such extensive praise of a particular current political figure, but also not the sort of thing that schools should be doing.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Some Thoughts on Multiple Blog Posts:

- "The Principal of a New Jersey Elementary School "

- "New Low: Beck and Right-Wing Media Minions Fearmongering About Kids to Attack Progressives":

- "School Children Singing the Praises of President Obama" (Apparently as a Public School Class Project):

An e-mail from a reader reminded me again of this debate — some people argue that "A times less than B" is "mathematically incorrect," "simply wrong," and so on. The theory is that "times" refers to multiplication, so "5 times less than B" to mean "B/5" is mistaken, though "5 times more than" to mean "5xB" (or possibly "6xB") would be fine.

This prompted me to do some more searching, and discover not only a usage of this phrase by Jonathan Swift (via Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of English Usage), but also by Isaac Newton ("If the Diameters of the Circles ... be made three times less than before, the Mixture will be also three times less; if ten times less, the Mixture will be ten times less"), Sir William Herschel ("remember that the sun on Saturn appears to be a hundred time less than on the earth"), Erasmus Darwin, Robert Boyle, John Locke, and more. Nor is this some archaic usage; it remains routine today.

What's going on here? The correspondent whose message prompted me to repost about this suggested that "A times less than B" might be a calque — "a loan translation, esp. one resulting from bilingual interference in which the internal structure of a borrowed word or phrase is maintained but its morphemes are replaced by those of the native language, as German halbinsel for peninsula" — from my native Russian, where "X raz men'she [or men'eye] chem" is routine. But that hardly explains Newton and Herschel, I think.

Rather, I think what's going on in the critics' minds is itself a sort of calque, though a calque from mathematics to human language. It's true that if you view "times" as "x" and "less" as "-," then "A times less than B" is either literally meaningless, or corresponds to "B-AxB." But of course in English, including the English used by scientists of the highest caliber, "times" doesn't always mean "x" and "less" doesn't always mean "-." We see that from the very examples I just gave, as well as from observed common usage.

Nor can you somehow disprove my assertion by "logic" of the "but 'times' means multiplication!" sort. That is the logic of the calque, and while calques sometimes do create usage (in Russian, for instance, the word for "rhinoceros" is "nosorog," since "rhino-" translates as "nos" [nose] and "-ceros" translates as "rog" [horn]), sometimes they don't. If you want to know what is an acceptable form (though just one of several acceptable forms) in English, including scientific English, is, the actual usage of Newton and Herschel — and, I suspect, countless lesser lights of today — tells us more than the abstract logic of literal translation from mathematical symbols.

This having been said, it may well be that "A times less than B" is suboptimal usage, precisely because it annoys enough people. (I am skeptical that it genuinely confuses a considerable number of people.) But to say that the usage is "simply wrong" or "mathematically incorrect" is to misunderstand the connection between mathematics and English, including the English used by people who are masters of mathematics.

Finally, a request for people who want to argue the contrary: Please preface your comments with "Isaac Newton was wrong about how to talk in English about mathematics, and I am right, because ...."

UPDATE: A comment, which regrettably failed to follow the eminently reasonable request in the preceding paragraph:

It's disappointing to see Mr. Volokh make this argument. The formulation is confusing. It could reasonably be argued that while 3X10 equals 30 then 3Xless than 10 would be a minus 20. People who use math in their work would never use the subject formulation. I thought it was limited to journalists.

First, it could reasonably be argued that "three times less than ten would be a minus twenty" -- if one has no idea about how actual humans talk. Of course no-one would use "three times less than ten" to mean that. Perhaps it's distracting or annoying, but it would take a lot to persuade me that anyone would actually think "'"If the Diameters of the Circles ... be made three times less than before'; does that mean 1/3 of the original, or negative two times the original?." Maybe Data, but then again he seems to have had some troubles with contractions, too.

Second, "people who use math in their work would never use the subject formulation"? Really? Might there be some evidence against this assertion available, I don't know, somewhere? I'm not sure, but I could have sworn I saw some ....

Related Posts (on one page):

- "Times Less Than":

- Ten Times Lower:

During the Bush years, we constantly heard the refrain, pushed especially by Paul Krugman, that the government was doing incompetent and corrupt things because conservative Republicans "don't believe in" government. Put the government in the hands of true-believing liberal Democrats, and incompetence and corruption will virtually disappear.

This always struck me as foolish, in part because the problems with government competence and integrity are structural, not individual, and in part because it required one to believe Krugman's fantasy that the Republican elite during the Bush years was dominated by wild-eyed libertarians intent on drowning the government in a bathtub, or something like that.

Anyway, here's the latest example of competence an incorruptibility from our liberal Democrat elites:

The Food and Drug Administration said Thursday that four New Jersey congressmen and its own former commissioner unduly influenced the process that led to its decision last year to approve a patch for injured knees, an approval it is now revisiting.

The agency's scientific reviewers repeatedly and unanimously over many years decided that the device, known as Menaflex and manufactured by ReGen Biologics Inc., was unsafe because the device often failed, forcing patients to get another operation.

But after receiving what an F.D.A. report described as "extreme," "unusual" and persistent pressure from four Democrats from New Jersey — Senators Robert Menendez and Frank R. Lautenberg and Representatives Frank Pallone Jr. and Steven R. Rothman — agency managers overruled the scientists and approved the device for sale in December.

All four legislators made their inquiries within a few months of receiving significant campaign contributions from ReGen, which is based in New Jersey, but all said they had acted appropriately and were not influenced by the money.

UPDATE: It's amusing to get accused of anti-Democrat "partisanship" in the comments for a post whose theme is that when given power the Democrats are just as corrupt and incompetent as the Republicans.

A large military spending bill moving through Congress contains a little-noticed outlay for Boston that has nothing to do with national defense: $20 million for an educational institute honoring late Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts.

It's not like the U.S. isn't broke or anything, and it's not like the Kennedys aren't filthy rich. And, if we truly wanted to honor "Sen. Kennedy's legacy," shouldn't the money be going to the poor or something? A very nice example of reverse Robin Hood--let's take from the taxpayers, and give to the Kennedys.

UPDATE: FWIW, I've been even more appalled over the years at the huge amount of taxpayer money spent "honoring" Ronald Reagan, starting with the huge Reagan trade center in downtown D.C. At least in Kennedy's case, it's not as if his legacy is supposed to be small government and low taxes.

Thursday, September 24, 2009

until the Supreme Court decides whether to grant certiorari in the Second or Seventh Circuit cases. The order is here. According to Declan McCullagh (CBSNews.com), "The justices are scheduled to discuss those cases on September 29, and are likely to announce their decision [on whether to hear the cases] soon after."

(Note: I am delighted to put up this guest post by my Washington College of Law, American University colleague Amanda Frost, on the new DOJ policy on the state secrets doctrine. Amanda has done important academic writing in this area, including this 2007 Fordham Law Review article, as well as other areas related to federal courts, including this provocative recent piece in the Virginia Law Review, Overvaluing Uniformity. Amanda, thanks and welcome!)

As Jonathan and Orin have already noted, the Department of Justice issued a new policy regarding use of the state secrets privilege on Wednesday. In a memo, Attorney General Holder declared that the privilege should be reserved for cases in which the privilege is “necessary to protect information” that “could reasonably be expected to cause significant harm to the national defense or foreign relations”—a narrower standard than used in the past. Most important, the new policy establishes several additional layers of government review before the privilege can be asserted, culminating in the required pre-approval of the Attorney General himself. Holder also promises to report regularly to Congress regarding use of the privilege.

The new policy should be welcomed not only by critics of the privilege, but also by its fans. As the Obama Administration surely realized, the privilege was in danger of being limited by both the courts and Congress, since at least some members of both branches had lost faith in the executive’s ability to assert the privilege in good faith.

Ever since the Supreme Court first recognized the privilege in its 1953 decision in Reynolds v. United States, the lower courts have mostly deferred to executive claims of privilege, and Congress has chosen not to regulate or limit its use. Recently, however, the executive’s increasing reliance on the privilege as grounds for outright dismissal of cases challenging the legality of its conduct inspired the other two branches to push back. In the past few years, a few lower courts have denied claims of privilege on the ground that the government exaggerated the risks to national security of disclosure, and even speculated that the executive is too self-interested to be completely trusted with its use.

For example, in Mohamed v. Jeppesen Dataplan, Inc., the Ninth Circuit commented that the executive might assert the privilege to avoid “embarrassment” rather than preserve state secrets, and thus refused to defer to the executive’s claimed need for secrecy in a case challenging the legality of extraordinary rendition. Congress is also seeking to take back control of the privilege. A bill entitled The State Secrets Protection Act, currently pending in the House, would limit and guide executive assertions of the privilege.

By voluntarily checking its own assertion of the privilege, the Administration may have slowed the momentum by these other two branches to establish greater restrictions on executive use of the privilege. For those, like myself, who are concerned about the privilege’s abuse in the hands of any executive, the new policy is a mixed blessing. Yes, I am happy to see the Administration voluntarily establish constraints on its use of the privilege, but I am hesitant to leave the privilege completely to the executive’s discretion. Ironically, then, the very policy shift that limits the privilege today may be the one that prevents courts and Congress from limiting abuse of the privilege in the future.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Zazi Detention Memo:

- Zazi Indicted on WMD Charges:

Yale Law School has organized a conference on The Constitution in 2020, a much-discussed recent book that puts together contributions by numerous prominent left of center scholars on the future of constitutional law. To their credit, the conference organizers have chosen to invite scholars with a wide range of viewpoints to the conference, including some who are conservative or libertarian. I will be appearing on the panel on Localism and Democracy, along with Ernest Young (Duke), Rick Schragger (Virginia), Ethan Leib (UC Hastings), and Judith Resnik (Yale, author of the chapter on federalism in The Constitution in 2020). The conference organizers have also created a website where each participant can summarize their presentations in a short blog post. Mine is available here. I include a brief excerpt below:

American federalism faces both great promise and serious dangers over the next few years. One of the most important advantages of federalism is the ability to “vote with your feet” – to leave a state with oppressive or ineffective policies and move to a better one . . . Increasing mobility and declining information costs give state and local governments stronger incentives to adopt policies that will be attractive to migrants. Revenue-hungry state governments know that valuable taxpayers will depart if they raise taxes too high or provide poor public services....

Unfortunately, American federalism is imperiled by the ongoing growth of federal power, especially the increasing dependence of state governments on federal funds. Our system has been successful in part because state governments have historically been forced to raise most of their revenue themselves. State governments that raise their own funds have strong incentives to adopt policies that promote economic growth and attract potential migrants. A state that falls behind its rivals is likely to lose its tax base. But states that can rely on federal funding to meet their fiscal needs face much less competitive pressure and are therefore less likely to adopt good policies.....

Federalism has also been weakened by the expansion of Congressional regulatory authority. The federal government has come to regulate almost every aspect of American society. This trend accelerated under the Bush Administration, which pushed through legislation expanding federal control of education and health care, and supported federal preemption of a variety of state laws, including ones permitting assisted suicide and the use of medical marijuana. The more policy areas come under federal control, the less the scope for interjurisdictional competition at the state and local level....

The 21st century could be an extraordinarily successful time for American federalism - but only if we restrain the growth of federal power.

Posts by the other participants are also available at the Constitution in 2020 blog site. The conference at YLS will be held October 2 to October 4. They are well worth reading if you are interested in the future of federalism. Yale has posted the conference schedule on its website.

UPDATE: In the original version of this post, I mislabeled Prof. Ernest Young's school affiliation. I apologize for the error, which has now been corrected.

Some people have argued that (1) statutes and constitutions should generally not be read in ways that render particular provisions superfluous, and (2) therefore the Free Press Clause should be read as providing special protection for the institutional press, beyond what the Free Speech Clause provides for other speakers.

I generally agree with point (1), but I don't think that point (2) follows. Protection for the "freedom of speech, or of the press" can quite sensibly be understood as ensuring that both speech (spoken words) and press (printed words) are to be equally protected (and perhaps other communication would be protected as well).

Without the Free Press Clause, the First Amendment might have been understood as not covering material that is printed and thus capable of being broadly disseminated. (One can imagine a government official arguing that speech, or even a handwritten letter, is all well and good, but printed material is much more dangerous; in fact, English history had been full of similarly justified restrictions on printing.) Without the Free Speech Clause, the First Amendment might have been understood as only covering material that is printed and thus capable of being broadly disseminated. Reading both clauses as protecting the same context, albeit in both media, doesn't make either provision superfluous.

Indeed, modern discussions of freedom of speech often cast it broadly enough to cover all communication, whatever the medium. But this broad understanding of the provision was likely itself molded by the breadth of the "freedom of speech, or of the press" language. To the extent that even newspaper publication is often described as protected under the Free Speech Clause, that's so precisely because the accompanying Free Press Clause has created a legally culture in which printed speech is as seen as no less protected than other speech.

I should note that, even independently of the above, I don't think the "press" must refer to the press as a business, as opposed to the press as a technology. But in any event, "freedom of speech, or of the press" strikes me as providing equal protection under both clauses, not special protection under one or the other.

Related Posts (on one page):

I was also pleased by this footnote from the Fourth Circuit's free speech / funeral picketing decision:

Neither the Supreme Court nor this Court has specifically addressed the question of whether the constitutional protections afforded to statements not provably false should apply with equal force to both media and nonmedia defendants. The Second and Eighth Circuits, however, have rejected any media/nonmedia distinction. Like those two circuits, we believe that the First Amendment protects nonmedia speech on matters of public concern that does not contain provably false factual assertions. Any effort to justify a media/nonmedia distinction rests on unstable ground, given the difficulty of defining with precision who belongs to the "media."

Sounds exactly right to me.

Related Posts (on one page):

- The Free Press Clause:

- The First Amendment and the Media/Nonmedia Distinction:

- Free Speech and Funeral Picketing:

Max Feinberg's will provided that all his property would go into a trust. During his wife Erla's life, she'd get income from the trust. When she died, the property would go to their descendants, but providing that any descendant who married a non-Jew, and whose spouse didn't then convert to Judaism within a year of the marriage, would be "deemed deceased" and would forfeit the share. Erla also had a "power of appointment" under which she could reassign which descendants could benefit from the trust. Erla exercised this power precisely the way that Max provided in his will — by disinheriting the four or out of five grandchildren who married non-Jews.

A complicated decision today from the Illinois Supreme Court, in In re Feinberg, upheld the validity of Erla's decision, but left open the broader question whether Max's wishes could have been enforced in the absence of the power of appointment exercised by Erla:

[T]his is not a case in which a donee, like the nephew in the illustration, will retain benefits under a trust only so long as he continues to comply with the wishes of a deceased donor. As such, there is no “dead hand” control or attempt to control the future conduct of the potential beneficiaries. Whatever the effect of Max’s original trust provision might have been, Erla did not impose a condition intended to control future decisions of their grandchildren regarding marriage or the practice of Judaism; rather, she made a bequest to reward, at the time of her death, those grandchildren whose lives most closely embraced the values she and Max cherished.

Still, the decision had some interesting language that might be relevant more broadly:

Michele argues that the beneficiary restriction clause discourages lawful marriage and interferes with the fundamental right to marry, which is protected by the constitution. She also invokes the constitution in support of her assertion that issues of race, religion, and marriage have special status because of their constitutional dimensions, particularly in light of the constitutional values of personal autonomy and privacy.Because a testator or the settlor of a trust is not a state actor, there are no constitutional dimensions to his choice of beneficiaries. Equal protection does not require that all children be treated equally; due process does not require notice of conditions precedent to potential beneficiaries; and the free exercise clause does not require a grandparent to treat grandchildren who reject his religious beliefs and customs in the same manner as he treats those who conform to his traditions.

Thus, Michele’s reliance on Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), is entirely misplaced. In Shelley, the Supreme Court held that the use of the state’s judicial process to obtain enforcement of a racially restrictive covenant was state action, violating the equal protection clause of the fourteenth amendment. This court, however, has been reluctant to base a finding of state action “on the mere fact that a state court is the forum for the dispute.” Indeed, Shelley has been widely criticized for a finding of state action that was not “‘supported by any reasoning which would suggest that “state action” is a meaningful requirement rather than a nearly empty or at least extraordinarily malleable formality.’” Adoption of K.L.P., 198 Ill. 2d at 465, quoting L. Tribe, American Constitutional Law 1698 (2d ed. 1988).

The court reversed a 2-1 appellate court decision to the contrary, which I blogged about last year. Thanks to How Appealing for the pointer.

Najibullah Zazi, the Denver man believed to be the central figure in a terror plot against the New York City transit system, has officially been indicted on charges of conspiracy to use weapons of mass destruction against persons or property in the United States, CBS 2 has learned.Some people had wondered why Zazi had initially been charged just with lying to investigators, and not terrorism offenses: My assumption was that the government needed time to complete a forensic examination of the groups' computers to see what they could find.

Zazi was scheduled to appear in court on Thursday in Denver on a count of lying to terrorism investigators. The new charge of conspiracy to use weapons of mass destruction was filed in New York City, and authorities plan to transfer him to the federal court in Brooklyn to face the new charges.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Zazi Detention Memo:

- Zazi Indicted on WMD Charges:

Here's the report, published Tuesday. An excerpt from the Summary:

The two main criteria which the courts would likely look to in order to determine whether legislation is a bill of attainder are (1) whether “specific” individuals or entities are affected by the statute, and (2) whether the legislation inflicts a “punishment” on those individuals. Under the instant bills, the fact that ACORN and its affiliates are named in the legislation for differential treatment would appear to meet a per se criteria for specificity.

The U.S. Supreme Court has also identified three types of legislation which would fulfill the “punishment” prong of the test: (1) where the burden is such as has “traditionally” been found to be punitive; (2) where the type and severity of burdens imposed are the “functional equivalent” of punishment because they cannot reasonably be said to further “non-punitive legislative purposes;” and (3) where the legislative record evinces a “congressional intent to punish.” The withholding of federal contracts or grants does not appear to be a “traditional” punishment, nor does the legislative record so far appear to clearly evince an intent to punish. The question of whether the instant legislation serves as the functional equivalent of a punishment, however, is more difficult to ascertain.

While the regulatory purpose of ensuring that federal funds are properly spent is a legitimate one, it is not clear that imposing a permanent government-wide ban on contracting with or providing grants to ACORN fits that purpose, at least when the ban is applied to ACORN and its affiliates jointly and severally. In theory, under the House bill, the behavior of a single employee from a single affiliate could affect not only ACORN but all of its 361 affiliates. Thus, there may be issues raised by characterizing this legislation as purely regulatory in nature. While the Supreme Court has noted that the courts will generally defer to Congress as to the regulatory purpose of a statute absent clear proof of punitive intent, there appear to be potential issues raised with attempting to find a rational non-punitive regulatory purpose for this legislation. Thus, it appears that a court may have a sufficient basis to overcome the presumption of constitutionality, and find that it violates the prohibition against bills of attainder.

My much more tentative thoughts on the subject are here.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Congressional Research Service on Whether the "Defund ACORN Act" Is an Unconstitutional Bill of Attainder:

- Would Defunding ACORN Be an Unconstitutional Bill of Attainder?

The Fourth Circuit has just reversed — in Snyder v. Phelps — the $5 million intentional infliction of emotional distress / invasion of privacy verdict against the Phelpsians (that's the "God Hates Fags" group) who picketed the funeral of a slain soldier.

The court essentially concluded that, at least where speech on matters of public concern is involved (see pp. 25-26), the First Amendment precludes liability based on "statements on matters of public concern that fail to contain a 'provably false factual connotation'" (see pp. 16-20). This applies not just to libel liability, but also liability for intentional infliction of emotional distress and intrusion upon seclusion (the specific form of invasion of privacy alleged here). If the speech fits within "one of the categorical exclusions from First Amendment protection, such as those for obscenity or 'fighting words'" (p. 18 n.12) it might be actionable. But if it's outside those exceptions, then it can't form the basis for an intentional infliction of emotional distress or intrusion upon seclusion lawsuit — regardless of whether it's "offensive and shocking," or whether it constitutes "intentional, reckless, or extreme and outrageous conduct causing ... severe emotional distress" (p. 23).

I think the court was quite right, for the reasons I gave in my earlier criticisms of the district court's allowing the verdict. In particular, the decision helps forestall similar liability for other allegedly outrageously offensive speech, such as display of the Mohammed cartoons (or other restrictions on such speech, such as campus speech codes' being applied to punish display of the cartoons).

The court did leave open the possibility that some content-neutral restrictions on funeral picketing may be imposed (p. 32), but it didn't discuss this in detail. For more on that, see here.

One of the three panel members, Judge Shedd, didn't reach the First Amendment issue, but concluded that (1) there wasn't intrusion upon seclusion under Maryland law because the protest was in a public place, and not even very near the funeral (p. 40), (2) the protest was not "extreme and outrageous" enough for purposes of the emotional distress tort because it was "confined to a public area under supervision and regulation of local law enforcement and did not disrupt the church service."

Thanks to How Appealing for the pointer.

Related Posts (on one page):

- The Free Press Clause:

- The First Amendment and the Media/Nonmedia Distinction:

- Free Speech and Funeral Picketing:

I'm pleased to report that the city of Pipestone, Minnesota (pop. 4000) has amended City Code ch. 10 § 10.01, subd. 1E to read

It is unlawful for any person to: ...

E. Possess any other dangerous article or substance for the purpose of being used unlawfully as a weapon against another; ...

It had earlier read,

It is unlawful for any person to: ...

E. Possess any other dangerous article or substance for the purpose of being used lawfully as a weapon against another; ...

I ran across this in doing research for my article on nonlethal weapons, and e-mailed the city attorney's office to ask whether this was a typo; I was told that it was, and then to my surprise was told that -- now that they knew about it -- the city would change it. Woohoo! Now that's high impact law reform work for you. I hope my dean gives me suitable credit.

(Note that the change happened a few months ago, but I only now remembered to check on whether it had indeed happened.)

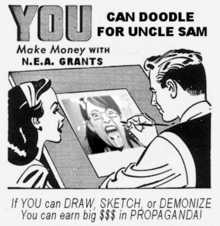

Iowahawk let's us know about the newest way to profit from the government's efforts to promote the arts:

Earn Big $$$ the NEA Way!

It's true — U.S. government demand for art and art-like products has never been higher! Uncle Sam and the good folks at the National Endowment for the Arts are on the lookout for go-getting, obedient artists like you for a fast-paced career in state propaganda. With the quick and easy Federal Art Instruction Institute course, now you too can get a first class ticket on the federal art gravy train!

And this ad is "just the beginning" (tip to Instapundit).

To see an example of this, consider the following hypothetical exchange over how much privacy Congress should extend to e-mail. I'll make the exchange between "Complicated Karen" and "Clear Chris," who are both trying to figure out the law of e-mail privacy and what Congress should do. Clear Chris wants a clear and simple rule; Complicated Karen is concerned with making sure the law produces sensible results in different settings.

Complicated Karen: I've been thinking about how much privacy the law should give to private e-mails held by an ISP. A lot of people think e-mail should be protected by a warrant requirement. What do you think?Of course, none of this suggests that clear rules are bad. To the contrary, they are the ideal, in my view. But clarity and simplicity are only some of the goals of legislation, and I don't think it works to simply assume that we necessarily want the law to be very simple and very clear no matter what. Put another way, sometimes the law is complicated not because of those darn lawyers, or because of evil interest groups, but because it needs to be complicated to avoid being an ass.

Clear Chris: I completely agree. I propose a simple rule: E-mail should be protected by a warrant.

Complicated Karen: Great. Now let's start thinking about some exceptions. Imagine an Internet subscriber wants the ISP to disclose the contents of his e-mail. Maybe he has forgotten the password, or he needs an authenticated version. Should we have an exception for consent?

Clear Chris: Well, yes, of course. If the person really consents, then the government shouldn't need a warrant. That's obvious.

Complicated Karen: Great. What kind of standard would you choose for consent? Knowing? Knowing and voluntary? Intelligent? Is it consent in fact? Would you allow implied consent? And what about third party consent? How about business e-mail?

Clear Chris: Woah, that's a lot of questions! I don't really know, to be honest. I just want the exception to be clear so people can understand it.

Complicated Karen: Sure, I agree, clear is great. At the same time, we need to think about just what kind of consent you have in mind. Otherwise it will just punt the issue for the courts to make up the law later on. Moving along, what about an exception for emergencies? Should we have an emergency exception? For example what if the police tip off the ISP that the e-mail is being used by a kidnapper, and the government would need several hours or more to get a warrant. Should we allow emergency disclosure if the ISP wants to disclose?

Clear Chris: I don't know, once we start getting exceptions, it seems like the exceptions are going to swallow the rule. But I'm not a nut; if there's really a kidnapping, and the ISP is willing to disclose, I think an emergency exception for kidnapping is reasonable. But I want the exception limited to kidnapping.

Complicated Karen: How about terrorists attacks? Serial killers? Maybe we should craft a general exception for severe emergencies?

Clear Chris: I'll have to think about that one; I'm pretty skeptical, but I'm not sure I would want to totally rule that out. Let's come back to that one.

Complicated Karen: Sure. What about if the ISP is outside the U.S.? What then?

Clear Chris: Who has an e-mail account outside the U.S.?

Complicated Karen: A lot of people do, actually. Someone in the US might have an account with servers in Canada. And for that matter, someone in Paris might have a Gmail account in the U.S. Do you want to require a warrant for all of these cases?

Clear Chris: I've never thought about that one, I have to admit. But well, yeah, sure, let's have a warrant requirement for those. I want a clear and simple rule, so let's keep it clear and simple.

Complicated Karen: Sure, that's fine. But to do that, we're going to modify some other laws. Under current U.S. law, U.S. officials can't get a warrant for overseas: warrants are traditionally for U.S. use only. And how do you want to create U.S. jurisdiction over crimes occurring abroad? If a person commits a crime in France, that can't authorize a U.S. warrant under U.S. law. We either need to negotiate a treaty with the French government to handle that, or else we can say that French crimes committed in France are U.S. crimes, too, allowing warrants to be issued in the U.S.

Clear Chris: Yikes, are you nuts? Suddenly you're talking about the treaties and French law, and all I wanted to do was have a simple rule! You keep trying to make things complicated. Why not just make it simple?

Complicated Karen: I'm trying to keep it simple, actually. But to make the law what you want it to be, you need to think about these issues: Otherwise you'll announce a simple rule but it won't have any legal effect because of other aspects of existing law.

Clear Chris: Lawyers! You guys always like to make things complicated; No wonder you bill by the hour.

-- and rejection of the "must prevent hostile environment harassment" justification for broad campus speech codes -- from Judge George King in Lopez v. Candaele.

The analysis is generally focused on campus speech codes, and distinguishes hostile work environment harassment law generally from similar restrictions emposed on college students. But part of its reasoning can also apply to First Amendment challenges to the application of hostile work environment harassment law to otherwise protected speech:

Defendants quote the Supreme Court’s statement in R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, 505 U.S. 377 (1992), that “since words can in some circumstances violate laws directed not against speech but against conduct (a law against treason, for example, is violated by telling the enemy the Nation’s defense secrets), a particular content-based subcategory of a proscribable class of speech can be swept up incidently within the reach of a statute directed at conduct rather than speech.” This reliance on R.A.V. misconstrues the context and meaning of the Court’s discussion and mistakes its relevance to this case. In context, the Court was attempting to distinguish between instances where content-based regulation of a subcategory of otherwise proscribable speech is unconstitutional (as in the St. Paul ordinance at issue) from those where “a particular content-based subcategory of a proscribable class of speech can be swept up incidentally within the reach of a statute directed at conduct rather than speech.” The issue before us is whether the Policy, in including expression within the scope of its regulation, unduly reaches a substantial amount of otherwise protected speech. It is no response to assert that a law may regulate a content-based subclass of unprotected speech that is swept up incidentally within the reach of a law targeting conduct rather than speech. Indeed, the Court went on to observe that “[w]here the government does not target conduct on the basis of its expressive content, acts are not shielded from regulation merely because they express a discriminatory idea or philosophy.” Here, the Policy is undeniably aimed at the content of the expression by prohibiting speech involving certain content, i.e., sexist comments, insulting remarks or intrusive comments about one’s gender.

Defendants also cite the Court’s comment that “sexually derogatory ‘fighting words,’ among other words, may produce a violation of Title VII’s general prohibition against sexual discrimination in employment practices, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2; 29 CFR § 1604.11 (1991).” They argue that “[t]he [R.A.V.] Court singled out a time-tested definition of sexual harassment as an example of a valid proscription of ‘sexually derogatory fighting words.’” If this argument means that fighting words can be within the cited CFR definition of sexual harassment, it is both correct and irrelevant. Our conclusion is not that the Policy has no valid application. Rather we held that it was unconstitutionally overbroad by sweeping within its reach a substantial amount of protected speech. If, on the other hand, Defendants mean that all speech that offends this definition is necessarily proscribable as sexually derogatory fighting words, then we reject this argument as an unwarranted and unconstitutional enlargement of what constitutes fighting words.

This fits well with the argument about R.A.V. that I've made as to hostile work environment harassment law.

This case stems from the incident in which an L.A. City College speech class professor refused to grade a student's presentation, apparently because of the religious nature of the student's presentation, the student's expression of opposition for same-sex marriage in the presentation, or both. (The professor apparently also called the student a "fascist bastard" in front of the class for having supported the anti-same-sex-marriage Prop. 8, and refused to let the student finish the presentation.) The case filed over that became a general challenge to the campus speech code, which the court preliminarily enjoined in July. The decision I link to today rejects the defendants' motion for reconsideration.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Further Defense of College Students' First Amendment Rights

- Los Angeles City College "Sexual Harassment" Policy Preliminarily Enjoined on First Amendment Grounds:

I have read with dismay Eric's defense of the expectation that legislators should not read legislation upon which they will vote. I am dismayed because I think has adopted a caricature of the "Read the Bill" position, and because his post reflects an unrealistic account of how legislatures work that is contrary to my experience of the legislative process on Capitol Hill and after ten years of work for an interest group in Washington, D.C. (during which I was involved in drafting, commenting upon and analyzing legislative language with representatives and their staff, among other things), and because it presents an overly idealized view of the role of "experts" within our political system.

No one denies that an effective legislative process requires a "division of labor" or "delegation to trusted subordinates." As I've already written below:

It is certainly appropriate for legislators to rely upon staff to draft legislation, review legislative proposals, and serve as a filter identifying bills that might be worthy of support, and so on.. Indeed, legislators could not do their jobs without such assistance. But this does not relieve legislators of reading those pieces of legislation that seek to enact.The question, which is relevant in private firms as well as in public entities, is what the proper scope of such delegations should be and, to what extent, principals need to perform certain functions for themselves.

The fact of the matter is that most legislative staff spend relatively little of their time reading and seeking to understand proposed legislation, let alone the small fraction of proposed legislation that may actually come up for a vote. They spend most of their time drafting correspondence, committee reports, talking points, memoranda, and the like, reading the same, as well as responding to constituent requests, meeting with staff from other offices, communicating with agencies, and so on. Legislative counsels also spend a decent amount of time drafting legislation. Under what I have proposed, none of this would change. Most legislative staff would continue to spend the vast majority of their time the same way that they do now. Committees and committee staff would still do the bulk of the heavy lifting on issues within their jurisdiction.

Since the legislator is the principal, I believe the legislator must, at the end of the day, assure him or herself that a given piece of legislation does what it is intended to do, and have some understanding of how it will achieve that end. This does not require tremendous expertise, but it does require, at a minimum, reading the bill's language (perhaps with the Ramseyer comparison already required in all House committee reports), meeting with more expert staff and, in many cases, hearing from experts. Is this too much to do for the small fraction of proposed legislation that may actually become law — that is, those pieces of legislation that pass committee and have a chance of a scheduled floor vote — hardly.

Two final points. First, Eric writes "political institutions are highly complex organizations that have evolved in response to needs and pressures." This is true as a descriptive claim, but it is hardly a justification of these political institutions. Much of what has evolved is the result of special interest pressures, rent-seeking, and the interests of political officials in evading accountability and capturing rents of their own. A process in which bills can be proposed and voted upon before anyone has had time to read them, including legislators and their staffs (as when omnibus amendments are offered on the floor on the eve of final passage), rarely serves the interest of "good legislation." It primarily serves those who seek either to push politically unpopular legislative changes or to enact targeted favors for prized constituencies. I've seen this first hand, and written up quite a few examples of the results. Does a "read the bill" obligation make all of this go away? Of course not. But it would make it harder for narrow interests to insert favors into highly complex bills, it would tend to encourage less complex legislation, and it would also further the goals of accountability and transparency. Legislators could be held accountable more easily, and the legislative process would be more transparent because if legislators had to have time to read the bills, then the interested public is more likely to have time to read legislation as well.Second, I reject Eric's claim that "simple rules rarely do any good in complex settings." I am actually quite sympathetic to the opposite view, but that's a discussion for another time. I have other things to attend to, including a lecture by former OIRA Adminsitrator Susan Dudley this afternoon.

[NOTE: I made a few edits to fix typos and awkward phrasings.]

Related Posts (on one page):

- Read the Bill -- A Reply to Eric:

- Should legislators read bills?

- Another Question for Those Who Want Legislators to Take the "Read the Bill" Pledge:

- Read the Bill - A Response to Orin:

- Questions for Those Who Want Legislators to Pledge To Read Every Word of Every Bill Before Voting:

- Should Lawmakers, Um, Read the Laws They're Voting On?:

I have read with dismay David and Jonathan’s arguments that all legislators should read all bills before voting. The argument fits a genre of populist rhetoric that claims that problems of governance can be solved with simple, common-sense rules, denying that political institutions are highly complex organizations that have evolved in response to needs and pressures, and that simple-sounding rules rarely do any good in complex settings. Here, we should keep in mind that the ultimate function of the legislature is to produce good law; that determining whether a particular law is good or bad is such a complex and subtle task that all legislatures have found it necessary to divide labor, form committees, hire staff, expect particular legislators to become experts and leaders in particular domains, and, indeed, delegate many functions to unelected expert regulators. This means that, for virtually any law, only a handful of people can possibly have a sophisticated understanding of the bill in question. It’s not a matter of reading the bill or not; it’s a matter of knowing about the problems that the bill hopes to solve. You can read the Bankruptcy Code from start to finish and even if you have an IQ of 200, you won’t understand it unless you also know how courts interpret the Code, how businesses respond to it, how state governments work around it, how regulators like the IRS use it, how it affects the incentives of individuals and firms, the meaning of moral hazard, something about risk aversion, how credit markets work, and on and on. I would say a half hour conversation with a credible expert would be vastly more useful than reading the Code, and if you say the legislators should talk to the expert and read the Code, you need also to believe that reading the Code will add to understanding and the legislator has nothing better to do with his time (for example, consult another expert with a different background, or consult an expert about another bill). I don’t believe that in any sophisticated private firm operating in a market one would ever see serious discussion along these lines: delegation to trusted subordinates is the essence of organization in complex settings, and people are evaluated on the basis of outcomes (profits, in the case of firms; the quality of the legislation they voted for, in the case of legislators), not on their conformity with simple-minded rules of behavior.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Read the Bill -- A Reply to Eric:

- Should legislators read bills?

- Another Question for Those Who Want Legislators to Take the "Read the Bill" Pledge:

- Read the Bill - A Response to Orin:

- Questions for Those Who Want Legislators to Pledge To Read Every Word of Every Bill Before Voting:

- Should Lawmakers, Um, Read the Laws They're Voting On?:

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

UPDATE: It seems that to get around the subscriber wall, you need to go here and click on the first link. Thanks to How Appealing for the tip.

(a) In General- Section 1030 of title 18, United States Code, is amended-- (1) in subsection (a)(5)--(A) by striking subparagraph (B); and(B) in subparagraph (A)--(i) by striking ‘(A)(i) knowingly’ and inserting ‘(A) knowingly’;(ii) by redesignating clauses (ii) and (iii) as subparagraphs (B) and (C), respectively; and(iii) in subparagraph (C), as so redesignated--(I) by inserting ‘and loss’ after ‘damage’; and(II) by striking ‘; and’ and inserting a period;(2) in subsection (c)--(A) in paragraph (2)(A), by striking ‘(a)(5)(A)(iii),’;(B) in paragraph (3)(B), by striking ‘(a)(5)(A)(iii),’; ‘(4)(A) except as provided in subparagraphs (E) and (F), a fine under this title, imprisonment for not more than 5 years, or both, in the case of-- ‘(i) an offense under subsection (a)(5)(B), which does not occur after a conviction for another offense under this section, if the offense caused (or, in the case of an attempted offense, would, if completed, have caused)-- ‘(I) loss to 1 or more persons during any 1-year period (and, for purposes of an investigation, prosecution, or other proceeding brought by the United States only, loss resulting from a related course of conduct affecting 1 or more other protected computers) aggregating at least $5,000 in value; ‘(II) the modification or impairment, or potential modification or impairment, of the medical examination, diagnosis, treatment, or care of 1 or more individuals;‘(III) physical injury to any persons; ‘(IV) a threat to public health or safety;‘(V) damage affecting a computer used by or for an entity of the United States Government in furtherance of the administration of justice, national defense, or national security; or ‘(VI) damage affecting 10 or more protected computers during any 1-year period; or ‘(ii) an attempt to commit an offense punishable under this subparagraph; ‘(B) except as provided in subparagraphs (E) and (F), a fine under this title, imprisonment for not more than 10 years, or both, in the case of--‘(i) an offense under subsection (a)(5)(A), which does not occur after a conviction for another offense under this section, if the offense caused (or, in the case of an attempted offense, would, if completed, have caused) a harm provided in subclauses (I) through (VI) of subparagraph (A)(i); or ‘(ii) an attempt to commit an offense punishable under this subparagraph; ‘(C) except as provided in subparagraphs (E) and (F), a fine under this title, imprisonment for not more than 20 years, or both, in the case of-- ‘(i) an offense or an attempt to commit an offense under subparagraphs (A) or (B) of subsection (a)(5) that occurs after a conviction for another offense under this section; or ‘(ii) an attempt to commit an offense punishable under this subparagraph; ‘(D) a fine under this title, imprisonment for not more than 10 years, or both, in the case of-- ‘(i) an offense or an attempt to commit an offense under subsection (a)(5)(C) that occurs after a conviction for another offense under this section; or ‘(ii) an attempt to commit an offense punishable under this subparagraph; ‘(E) if the offender attempts to cause or knowingly or recklessly causes serious bodily injury from conduct in violation of subsection (a)(5)(A), a fine under this title, imprisonment for not more than 20 years, or both; ‘(F) if the offender attempts to cause or knowingly or recklessly causes death from conduct in violation of subsection (a)(5)(A), a fine under this title, imprisonment for any term of years or for life, or both; or ‘(G) a fine under this title, imprisonment for not more than 1 year, or both, for--‘(i) any other offense under subsection (a)(5); or ‘(ii) an attempt to commit an offense punishable under this subparagraph.’; and (D) by striking paragraph (5); and (3) in subsection (g)-- (A) in the second sentence, by striking ‘in clauses (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), or (v) of subsection (a)(5)(B)’ and inserting ‘in subclauses (I), (II), (III), (IV), or (V) of subsection (c)(4)(A)(i)’; and (B) in the third sentence, by striking ‘subsection (a)(5)(B)(i)’ and inserting ‘subsection (c)(4)(A)(i)(I)’. (b) Conforming Changes- Section 2332b(g)(5)(B)(i) of title 18, United States Code, is amended by striking ‘1030(a)(5)(A)(i) resulting in damage as defined in 1030(a)(5)(B)(ii) through (v)’ and inserting ‘1030(a)(5)(A) resulting in damage as defined in 1030(c)(4)(A)(i)(II) through (VI)’.Interesting, isn't it? I don't really have anything to say about it that isn't obvious from the text, but I thought you might want to read the text for yourself so you can understand what Congress did. It's always good to read the bill.

Stanford Professor and Hoover Institution senior fellow John B. Taylor has started up a blog, Economics One. His short Hoover Press book on the monetary origins of the financial crisis, Getting Off Track: How Government Actions and Interventions Caused, Prolonged, and Worsened the Financial Crisis, was a surprise intellectual intervention in analysis of the crisis and an instant mini-best-seller, as this kind of book goes. I don't pretend to any knowledge of monetary economics, but I am already a fan of Professor Taylor's blog (he makes interesting comments in a new posting, by the way, on his recent co-authored piece in the WSJ on the effect (non) of the stimulus).

(Tangentially, the director of the Hoover Institution remarked at a meeting on something different I was at yesterday that, just from a pure publishing standpoint, the speed with which Hoover Press was able to produce a very short, elegantly written essay, put it in a handsome hardback format with good design, high quality paper stock, great graphics, and get it out via Amazon backed up by Hoover Press directly to readers has altered how the institution thinks about in-house production. I wonder whether other think tanks or university presses will consider this model? Getting Off Track has sold something like 20,000 copies, and I would guess 80% have been via Amazon. I mean, you have to start with a great book, and let it go viral - but reducing the production cycle from over a year to a few weeks, with readers knowing they can just hit the one-click button and get two day Amazon Prime delivery ...)

Apropos the recent discussion on this site, the Federalist Society is hosting a debate between David Rivkin and Jonathan Turley on the constitutionality of an individual mandate in Washington, D.C. tomorrow. Details here.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Read the Bill -- A Reply to Eric:

- Should legislators read bills?

- Another Question for Those Who Want Legislators to Take the "Read the Bill" Pledge:

- Read the Bill - A Response to Orin:

- Questions for Those Who Want Legislators to Pledge To Read Every Word of Every Bill Before Voting:

- Should Lawmakers, Um, Read the Laws They're Voting On?:

Politoc reports that ACORN has filed suit in Maryland against the two young film makers who recorded their visits to ACORN offices disguised as a pimp and prostitute seeking tax and other assistance. ACORN's suit also extends to the internet news site, Breitbart.com. The complaint is here. More from the Washington Post here.

My father Jerry Kopel served 22 years in the Colorado House of Representatives. He represented part of northeast Denver, as a Democrat. Among the posts he held were Judiciary Committee Chairman and Assistant Minority Leader. (His website is here.) He did read every bill before voting on it. Sometimes he was the only legislator who did so; at other times during his tenure, there were a few others who did so, including Republican Tim Foster.

For 18 of the 22 years, he was a member of the minority party. By actually knowing what was in the bills, he was able to offer amendments to improve the bills, take out over-reaching provisions, and so on. More importantly, because he knew what the bills contained, he was not dependent on lobbyists to describe the bills to him. This was particularly important if the lobbying power on one side of a bill was very lopsided.

For example, in 1990 a bill to significantly expand Colorado's already-bad civil forfeiture laws was introduced. It passed the House Judiciary Committee 12-1. (Although my father served for many years on the Judiciary Committee, by that time he had switched to the Business Affairs Committee.) The weekend before it was due to come up on the floor of the House for a vote, he read the forfeiture bill. Speaking on the floor of the House, he showed the legislators that the bill was far more onerous than its lobbyists had claimed. The bill was defeated by a solid bi-partisan majority.

The Colorado Constitution requires that each bill shall only concern a single subject, which shall be clearly expressed in the title. This provision is sometimes stretched to the limit (and beyond) with broad titles such as "Concerning criminal justice" (the typical title for the District Attorneys' annual omnibus wish list). Even so, the single subject rule does help make legislation more comprehensible for citizen legislators.

One other data point on reading bills: When the NAFTA legislation was moving through Congress, Ralph Nader challenged the Senators and Representatives to read the bill, because, Nader said, reading it would change their minds. Colorado Republican Senator Hank Brown responded by reading the massive bill. As a result, he said, he changed his mind, and voted against it.