I recently purchased a copy of Volume I of the early criminal law treatise, William Hawkins, A Treatise of Pleas of the Crown; or, a system of the principal matters relating to that subject, digested under proper heads. At common law, non-misdemeanor English crimes were the causes of action brought in the King’s court — thus a treatise on pleas of the Crown was a treatise on major crimes. The Hawkins treatise was first published in 1716, and it is one of the handful of sources regularly used to understand the common law of crimes (together with Volume 4 of Blackstone’s Commentaries, the Third Part of Coke’s Institutes, and Hale’s Pleas of the Crown).

The copy I purchased is a 6th edition as reworked by Thomas Leach and published in Dublin in 1788. My understanding is that the Dublin editions were pirated: They were published in Dublin to get around English copyright law. Pirated or not, I found this one on the cheap. Nice original copies of Hawkins seem to run around $700 to $1,000, but I found this for only $30 (albeit just the 1st of two volumes, and in need of rebinding).

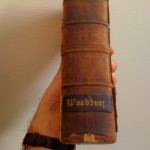

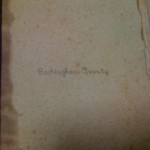

I mention all of this in the spirit of my recent post on the 19th Century Supreme Court letter because I found some intriguing markings in and on the book. Inside the front cover, I found two stamped markings, “Rockingham County.” And on the spine, there is a black label that says “Woodbury.” Here are photos of the spine, inside the front cover, and the title page of the treatise:

The combination of “Woodbury” and “Rockingham County” is intriguing because Justice Levi Woodbury, a Justice of the Supreme Court from 1845-1851, was born, raised, and buried in Rockingham County, New Hampshire. Indeed, a bit of googling revealed a 2006 advertisement for a 1733 legal treatise that had similar markings: The seller noted the possibility that the treatise came from the personal library of Justice Woodbury.

Wow, I thought to myself. Could this 1788 book, purchased for $30, have come from the personal collection of a mid-19th century Supreme Court Justice?

My research suggests it’s a possibility. In 1851, when Justice Woodbury died, his book collection was inherited by his son Charles Levi Woodbury, a Boston lawyer. Although some of those books were destoyed by fire in Boston in 1872, others survived:

What did survive the Boston fire were Charles Lev’s office law library and “a large and well selected library” of 1,000 volumes he had inherited in 1851 from his father, Levi Woodbury. Because he used his father’s Portsmouth estate as a summer home, some rare volumes now in the vault escaped destruction in 1872. The elder lawyer, politician and jurist’s library was said to contain “the best French authors; histories and memoirs, much of it very rare; numerous books on modern science and the practical arts; the works of statesmen; early history of Canada [and] of New England — a substantial collection, including several choice editions of the best English dramatists, poets and historians.”

At this point you’re thinking, wait, what are the chances that this book would happen to have been part of that collection? And how would we know it? Well, I don’t know anything for sure. But recall the stamped “Rockingham County” mark on the book. At first this seemed odd to me. Wouldn’t it be weird to stamp the county in which you live on your personal law books? But then I read about what Charles Woodbury did with his legal library. The library guide published by the Portsmouth N.H. Athenæum tells us:

Charles L. Woodbury bequeathed his non-Massachusetts legal library to the Rockingham County Court just as its new State Street courthouse was built in Portsmouth. There the Woodbury books remained until it was to be razed after the court moved to Exeter. It was then that Wyman Boynton rescued several hundred law books, many with signature of Levi Woodbury and other members of the local bar. Of particular interest are especially early printed legal works, although many are being sorted and processed.

These will join the Athenæum’s own legal collection that included a short run of the early American Law Journal (1808 -1817) and New Hampshire Laws published since the eighteenth century.

So it is seems likely that the “Rockingham County” stamp was added when the book was given to the Rockingham County Court and became part of the court’s collection. The “Woodbury” mark could indeed be from Justice Woodbury.

At the same time, it seems more likely that it came from the collection of his son Charles Levi Woodbury. We know the younger Woodbury had an extensive law office library, and this is the kind of work a practicing lawyer would have had in his office. Particularly so because the younger Woodbury had a practice that included criminal law; he was the U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts from 1857 to 1861. So I suppose we’ll never know which Woodbury first owned the book, but it seems the odds favor the book having come from the collection of the younger Woodbury.

How did the book come my way? I would guess that the Athenæum was going through Charles L. Woodbury’s collection, and in the course of sorting and processing them they decided to just get rid of some of the more common books. This volume would certainly qualify: Hawkins was a popular treatise, the cover is very worn, Volume 2 is missing, and the volume has no signature or personal markings other than the numbers “52/6” on the inside cover (perhaps indicating where in the library the book should go). It then made its way to DeWolfe and Wood Rare Books in Alfred, Maine, and I bought it online from them.

Anyway, this is all speculation, but hopefully it was of some modest interest to the legal history buffs among our readers.