|

Fear of Extremist Muslim Violence Suppresses Speech in the U.S.:

The AP reports:

Borders and Waldenbooks stores will not stock the April-May issue of Free Inquiry magazine because it contains cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad that provoked deadly protests among Muslims in several countries.

"For us, the safety and security of our customers and employees is a top priority, and we believe that carrying this issue could challenge that priority," Borders Group Inc. spokeswoman Beth Bingham said Wednesday.

The magazine, published by the Council for Secular Humanism in suburban Amherst, includes four of the drawings that originally appeared in a Danish newspaper in September, including one depicting Muhammad wearing a bomb-shaped turban with a lit fuse....

I have some sympathy for Borders here. It seems to me that leading bookstores, like leading universities, need to take some risks -- and, yes, even risks that involve potential risks to customers and employees -- in order to protect the marketplace of ideas that sustains them. Nonetheless, I can certainly see why Borders might worry about this risk.

The real point here, though, is that speech suppression caused by the threat of extremist Muslim violence has come to the U.S. We are all Danes now. What is the West, and what are we, going to do about it?

Free Speech and Tort Lawsuits Over Attacks on Bookstores:

Here's a tort law / constitutional law question, by the way, though please answer it only if you are a lawyer or legal researcher who is knowledgeable enough in the doctrine -- I'm not looking for abstract generalities, but concrete arguments based on current American legal rules:

Say that Borders or NYU decides to distribute the cartoons, or allow a meeting that displays the cartoons; and say that thugs respond with violence, which injures a patron or a student. (I set aside for the sake of simplicity injuries to employees, since, to my knowledge, damages claims against employers over such incidents would generally be governed by worker's compensation plans rather than tort law.)

Should Borders and NYU be held liable based on the theory that they negligently failed to employ extra security to protect against? Or should they have a First Amendment defense, because the tort theory underlying that lawsuit essentially imposes a tax on those who distribute highly controversial speech? Cf., for whatever it's worth, Forsyth County v. Nationalist Movement, 505 U.S. 123 (1992) (emphasis added), which struck down a policy under which parade organizers had to pay a permit fee (of up to $1000) based in part on the expected policing costs that stemmed from how controversial the parade would be:

The county envisions that the administrator, in appropriate instances, will assess a fee to cover "the cost of necessary and reasonable protection of persons participating in or observing said . . . activit[y]." In order to assess accurately the cost of security for parade participants, the administrator "'must necessarily examine the content of the message that is conveyed,'" estimate the response of others to that content, and judge the number of police necessary to meet that response. The fee assessed will depend on the administrator's measure of the amount of hostility likely to be created by the speech based on its content. Those wishing to express views unpopular with bottle throwers, for example, may have to pay more for their permit.

Although petitioner agrees that the cost of policing relates to content, contends that the ordinance is content neutral because it is aimed only at a secondary effect -- the cost of maintaining public order. It is clear, however, that, in this case, it cannot be said that the fee's justification "'ha[s] nothing to do with content.'"

The costs to which petitioner refers are those associated with the public's reaction to the speech. Listeners' reaction to speech is not a content-neutral basis for regulation. Speech cannot be financially burdened, any more than it can be punished or banned, simply because it might offend a hostile mob.

Harper's Magazine Apparently Publishing the Mohammed Cartoons,

with commentary by Art Spiegelman.

Robert Bidinotto asks whether Borders will likewise refuse to stock these (though I should note that I don't entirely agree with his analysis). I called the Borders on Westwood; the Harper's site lists that store as a place to buy the magazine, and the clerk there said they regularly carried out, but didn't have it now -- I don't know whether it's because the issue hasn't yet arrived (though the Chronicle article linked to above says that the issue was available on newsstands Tuesday), has sold out, or is not being carried by Borders.

It Appears Borders Is Carrying the Harper's Issue

That Contains the Mohammed Cartoons.

UPDATE: Just got the article and read it -- it is generally very good, though there's quite a bit in it that I disagree with. And it helps illustrate, I think, what some (including me) have argued: It's hard to seriously discuss the issue without showing the cartoons and talking about them one by one.

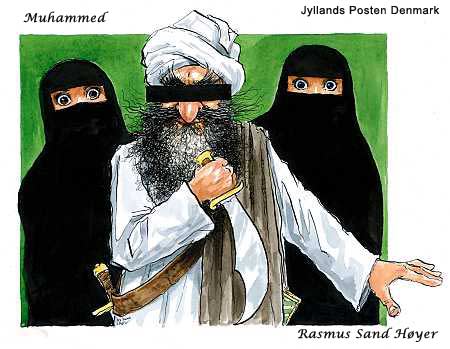

Incidentally, one of my disagreements with Art Spiegelman is in his characterization of the Mohammed-with-two-veiled-women cartoon as "An overtly racist caricature of an angry Muhammad." What's racist about it? That he has a big beard and a big nose? But they're not displayed in a way that makes them objects of mockery or derision -- the negative component of the image is his seeming anger, but that's not a racist commentary.

In any case, though, how can one possibly judge whether or not the cartoon is indeed racist -- as some commentators have alleged the cartoons generally, or some in particular, are -- without seeing it for yourself?

Finally, to Spiegelman's credit, he provides his own cartoon that he describes as "My final solution to Iran's anti-Semitic cartoon contest," which strikes me as on-topic, smart, and even humorous in its own blacker-than-black way.

"Racist" Cartoons:

A commenter questioned my questioning Art Spiegelman's statement that this cartoon is racist — not just critical of Islam, or at least of some strands of Islam, but racist (or perhaps more precisely "ethnically bigoted," though for our purposes we can view the two as roughly interchangeable):

I know that people have sometimes argued that any cartoons that depict stereotypical racial or ethnic features are racist; but I've never been quite persuaded about that, whether as to such cartoons that depict Jews (a common source of this argument) or as to cartoons that depict Arabs.

Cartoons, like illustrations generally, are supposed to provide images that at least have the air of verisimilitude. If one is to depict a generic Jew, a generic Arab, a generic Swede, or an archetypal Arab whose true appearance is unknown (here, Mohammed) one ought to depict him in a way that makes people recognize what is being discussed. "A conventional, formulaic, and oversimplified conception, opinion, or image" (the definition of stereotype) may be unsound if used as an overgeneralization about people's traits — but that's what cartooning requires. If you can't use characteristic features of a group's appearance, effective cartooning — or illustration generally — becomes much harder, in my view unjustifiably harder.

I think the matter is different if the features are portrayed in a way that makes them look ridiculous or disgusting. At some point, exaggeration, for instance a ridiculously beaked nose on a Jew or on an Arab, or exaggerated lips on a cartoon depicting someone black, does make the subject look that way, and may be seen as an aspersion on the ethnic group to which the person belongs. But the important point, in my view, is that this is true as to certain sufficiently exaggerated or distorted depictions, not as to depictions of stereotypical features generally.

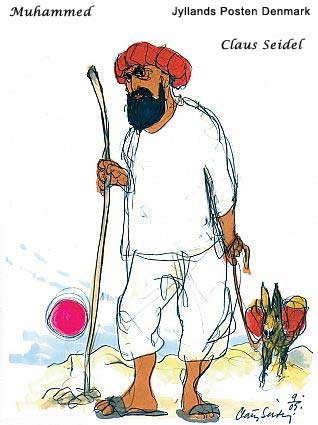

The cartoon does depict Mohammed negatively — but because of what he's doing, coupled with the fierce cast of his features (which is not necessarily linked to their stereotypical qualities). One might compare it, for instance, with this cartoon:

The features are comparable, though not identical; but the latter cartoon seems like a humanizing and even compassionate portrait. It's the message of hostility to a particular religious belief system embodied by Mohammed that differentiates the two, not that one uses somehow inherently "racist" imagery and the other doesn't.

In any case, that's my take on it. Perhaps I'm mistaken, but it seems to me that the permissible stereotyping vs. exaggeration to make the group look ridiculous or disgusting distinction is an important one, and that visual stereotyping can't be universally condemned at least where cartooning is concerned.

But, as I said before, the more important point is that one can't even have this discussion unless one can see the cartoons themselves — further evidence that it's unsound to argue, as the New York Times did, that "report[ing] on the cartoons but refrain[ing] from showing them" "seems a reasonable choice for news organizations that usually refrain from gratuitous assaults on religious symbols, especially since the cartoons are so easy to describe in words."

UPDATE: Thanks to Human Events Online for the high-resolution cartoons, and to reader Nels Nelson for the pointer to those cartoons.

Canada's Largest Retail Bookstore Bows To Fear of Anti-Cartoon Demonstrations,

and removes from its shelves the current issue of Harper's Magazine — the issue that reprints the cartoons in the context of an article by Art Spiegelman, the author of Maus and other graphic novels.

The cartoons are at the center of one of the most important censorship debates of this decade. Seeing them is necessary to evaluate the debate. Harper's is one of the leading general-interest magazines in North America. Art Spiegelman is one of the top cartoonists now living. And yet the fear of demonstrations — which presumably refers to the fear of violent demonstrations — apparently led Canada's largest retail bookstore to buckle. Sad.

From The Toronto Globe and Mail:

Canada's largest retail bookseller has removed all copies of the June issue of Harper's Magazine from its 260 stores, claiming an article by New York cartoonist Art Spiegelman could foment protests similar to those that occurred this year in reaction to the publication in a Danish newspaper of cartoons depicting the Prophet Mohammed.

Indigo Books and Music took the action this week when its executives noticed that the 10-page Harper's article, titled Drawing Blood, reproduced all 12 cartoons first published last September by Jyllands-Posten (The Morning Newspaper).

The article also contains five cartoons, including one by Mr. Spiegelman and two by Israelis, "inspired" by an Iranian newspaper's call in February for an international Holocaust cartoon contest "to test the limits of Western tolerance of free speech."

It's unclear what part, if any, the five cartoons played in the Indigo ban; phone calls to its Toronto headquarters were not returned yesterday. In 2001, Indigo founder and CEO Heather Reisman ordered all copies of Adolph Hitler's Mein Kampf pulled from stores, describing the book as "hate literature." Two years later, she helped found the powerful lobby group the Canadian Council for Israel and Jewish Advocacy.

In a memo obtained by The Globe and Mail that was e-mailed to Indigo managers yesterday about "what to do if customers question Indigo's censorship" of Harper's, employees are told to say that "the decision was made based on the fact that the content about to be published has been known to ignite demonstrations around the world. Indigo [and its subsidiaries] Chapters and Coles will not carry this particular issue of the magazine but will continue to carry other issues of this publication in the future." ...

If you have more information on this story, please post it in the comments. Thanks to reader John Thacker for the pointer.

We Are All Danes Now, Latest Installment:

The International Herald Tribune reports:

A leading German opera house has canceled performances of a Mozart opera because of security fears stirred by a scene that depicts the severed head of the Prophet Muhammad, prompting a storm of protest here about the renunciation of artistic freedom.

The Deutsche Oper in Berlin said it had pulled "Idomeneo" from its fall schedule after the police warned that the staging of the opera could pose an "incalculable risk" to the performers and the audience.

The Deutsche Oper's director, Kirsten Harms, said she regretted the decision but felt she had no choice because she was "responsible for all the people on the stage, behind the stage and in front of the stage."

Political and cultural figures throughout Germany condemned the cancellation, which is without precedent here. Some said it recalled the decision of European newspapers not to print satirical cartoons about Muhammad, after their publication in Denmark generated a furor among Muslims.

The decision seemed likely to fan a debate in Germany, and perhaps elsewhere in Europe, about whether the West was compromising its values, including free expression, to avoid stoking anger in the Muslim world....

What debate? Isn't this exactly what's happening here?

I should note that the opera is not quite rejecting Mozart as such: "The disputed scene is not part of Mozart's 225-year-old opera, but was added as a sort of coda by the director, Hans Neuenfels. In it, the king of Crete, Idomeneo, carries the heads of Muhammad, Jesus, Buddha and Poseidon, god of the sea, onto the stage, placing each on a stool.... 'The severed heads of the religious figures ... was meant by Neuenfels to make a point that "all the founders of religions were figures that didn't bring peace to the world."'"

But what they're doing is plenty bad enough -- they're surrendering their own artistic freedom by caving in to the fear of violence, and thus encouraging more threats of violence and more suppression of artistic freedom in the future.

Yes, I sympathize with organizations that feel the obligation to protect themselves and their viewers. But on balance such surrender, especially highly anticipatory surrender ("[t]his past summer, the Berlin police said they received a call from an unidentified person, who warned that the opera was 'damaging to religious feelings'[; t]he caller did not make a specific threat against the opera"), is both a disaster for artistic and political freedom, and I suspect encourages more violence than it avoids. Institutions that rely on this freedom need to be willing to run some risks to preserve it.

Finally, I think it's important that the change seems to be overtly motivated by fear of violence, rather than by genuine desire to avoid offending prospective viewers, or to avoid associating with what the organization sees as reprehensible ideas. The latter two justifications are aspects of one's artistic freedom: Artistic freedom includes the freedom to choose the art that one considers most worthy, and (generally speaking) that will attract viewers rather than repelling them. But the fear-of-violence justification is a surrender of that freedom.

|

|