The international gun prohibition movement has been working hard the past several years to pick up allies from other international interest groups. The prohibitionist tactic is to argue that civilian possession of firearms harms "X", where "X=the particular concern of the interest group." Thus, feminists are targeted with the claim that firearms possession harms women (even though firearms possession by women harms rapists); and human rights advocates are told that firearms possession harms human rights (even though firearms prohibition is the sine qua non for genocide). Similarly, economic development supporters are told that firearms possession by citizens harms economic development.

In the next issue of Engage, the journal of the Federalist Society, my co-authors Paul Gallant, Joanne Eisen, and I investigate the claim. We find that in Latin America, development failure long-preceded the proliferation of firearms among civilians. In Africa, the key impediments to development are malaria and AIDS, which thrive in Africa partly because of harmful policies encouraged by the United Nations bureaucracy. Finally, we conduct case studies of Kenya and Zambia, and detail how corrupt, undemocratic governments are the fundamental impediments to development. The international gun prohibition movement aggravates the problem, by allowing kleptocracies to shift the blame away from themselves, and to instead blame good citizens who only want to protect their families from government-sponsored violence.

Saturday, May 14, 2005

Friday, May 13, 2005

After a mentally disabled black man was found beaten, unconscious, and shivering on a fire ant mound in 2003, four white men charged in the crime could have faced 10 years in prison.

But folks in this poor, pine-locked Texas hamlet of 2,300 say they knew better.

On Friday, the four young men accused of severely injuring 44-year-old Billy Ray Johnson during a late-night pasture party are expected to be sentenced to probation or brief jail time after juries rejected more serious charges and recommended suspended sentences for two of them.

The victim survived the attack but can't walk without help or speak clearly.

Some white residents believe it is a fair outcome for a few "good boys" from prominent families with no previous legal trouble. But other residents, blacks and whites, say the sentences are far from fair and just another example of justice being tainted by small-town politics, racism and a court system that favors whites.

Related Posts (on one page):

----- Original Message -----Later, Starr adds a fuller explanation in another e-mail, forwarding on his response to Engel:

From: "Starr, Ken"

Sent: 05/11/2005 06:53 PM

To: "'Steven Engel'"

Subject: RE: misquoted on filibusters?

Steve:

I just watched the CBS report. Totally wrong employment of the snippet: I was condemning the Democrats for challenging judges based on philosophy. It was in that context that I made the radical departure point. Wow. Ken

I have now seen the CBS report. Attached is an exchange with Steve Engel at K&E-Washington, who alerted me earlier today to other dimensions of the wild misconstruction of what I said in the Gloria Borger interview.

Brief background: I sat on Saturday with Gloria for 20 minutes (approx.) and had a wide-ranging on-camera discussion. In the piece that I have now seen, and which I gather is being lavishly quoted, CBS employed two snippets. The "radical departure" snippet was specifically addressed — although this is not evidenced whatever from the clip — to the practice of invoking judicial philosopy as a grounds for voting against a qualified nominee of integrity and experience. I said in sharp language that that practice was wrong. I contrasted the current practice . . . with what occurred during Ruth Ginsburg's nomination process, as numerous Republicans voted (rightly) to confirm a former ACLU staff lawyer. They disagreed with her positions as a lawyer, but they voted (again, rightly) to confirm her. Why? Because elections, like ideas, have consequences. . . . In the interview, I did indeed suggest, and have suggested elsewhere, that caution and prudence be exercised (Burkean that I am) in shifting/modifying rules (that's the second snippet), but I likewise made clear that the "filibuster" represents an entirely new use (and misuse)of a venerable tradition.

Anyway, our folks here at Pepperdine's Public Information Office (who arranged the CBS interview) are scrambling to get the full transcript of the entire interview. But our friends are way off base in assuming that the CBS snippets, as used, represent (a) my views, or (b) what I in fact said.

Kindly feel free to share this message with anyone you deem appropriate. Ken

Related Posts (on one page):

- More Starr on the Filibuster:

- Blogging Judicial Nominations:

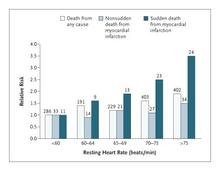

A French study of 5713 men collected resting and exercise data on pulse rates from 1967 through 1972. They then followed up on deaths in that group through 1994 (about one-quarter died).

They found, among other things, that resting pulse rates predicted sudden death from heart attacks, though such sudden deaths were only a small proportion of total deaths.

The lowest risk was for those with pulse rates of less 60 beats a minute. Reading from Figure 1, pulses of 60-64 and 65-69 led to roughly 1.5-2 times the relative risk of sudden death by heart attack (compared to the low pulse group). Resting pulses of 70-75 led to roughly 2.5 times the relative risk, and pulses of greater than 75 led to roughly 3.5 times the risk of sudden death by heart attack. [Since the pulse groups were divided by quintiles, the median should probably have fallen in the midlle group with pulses of 65-69.]

(Click to enlarge.)

There is more in the article on the predictive power of exercise pulse rates.

For those who want an easy, painless way to check their blood pressure and pulse, you might consider a blood pressure wrist cuff. Everyone in our extended family has at least one of these Omron HEM 609 wrist blood pressure cuffs. [I'm having problems getting a good Amazon link. At Amazon search for: omron 609 hem jpi.] Just put it around your wrist, press one button, and wait a minute for the results. It slowly contracts and then suddenly releases when it gets its blood pressure reading, which results in no excess restriction and extremely little discomfort.

A recent article by Prof. Steven Gey briefly cites in a footnote my Crime-Facilitating Speech piece, quickly describes my proposal, and then says:

Professor Volokh draws two exceptions to this rule [of generally protecting speech even though it's crime-facilitating]: first, when the information creates "extraordinarily serious harms," and second, when the speech "seems to have virtually no noncriminal uses." Volokh's analysis and conclusions are largely consistent with the arguments presented in this Article, although the protectiveness of Volokh's rule would depend on how narrowly the courts interpret Volokh's two exceptions. Volokh is aware of this problem, and is appropriately circumspect about the difficulties of defining the relevant harm threshold that triggers the exceptions to the rule.

As I read it, Prof. Gey is in some measure criticizing my approach, though also in some measure agreeing with it, both of which are perfectly fine. (OK, the latter is more fine than the former, but while I like it when people agree with me, that itself is hardly occasion for great joy, just like disagreement as such is no occasion for great sorrow.)

What particularly pleases me, though, is the last sentence: To me, one of the marks of sound and careful scholarship — as opposed to, say, effective advocacy or emotionally rewarding self-expression — is being aware of the problems in one's proposals, and therefore being appropriately circumspect about the difficulties of properly crafting the proposals. I try to always aim at this. I'm sure I often miss. But if Prof. Gey is correct that in this instance I succeeded, I am very glad indeed.

Congratulations to Todd Zywicki, newly elected trustee of Dartmouth College. Powerline has more.

Ann Althouse has a nice post analyzing Raich, the medical marijuana Commerce Clause case. She thinks that the government is likely to win.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Ann Althouse Ponders Raich,--

- Does Asking More Questions Tip the Outcome of Supreme Court Cases?--

Thursday, May 12, 2005

Apparently, the new practice is client-driven. A number of corporate clients want to decide what firms to hire and fire based on the race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation of the lawyers working on their cases, and the firms have now agreed to provide that information. As one person quoted in the story explains, a firm that assigns a team of lawyers with a gender/race/orientation mix that the client does not approve of will now be "history."

I have enabled comments. As always, civil and respectful comments only.

I'm pleased to say that I'll be posting occasionally at Ariana Huffington's new mass-blog. The great majority of my posts will still be here, but I'll occasionally pipe in there. Why? Precisely because the readers there are likely very different than the ones we get here (much as I love you folks!).

The decision, from a federal trial judge in Nebraska, is here. I think it's quite mistaken, and will be reversed on appeal. A few thoughts:

- The judge doesn't hold that there's a constitutional right to same-sex marriage as such. Rather, he holds that the recently enacted Nebraska constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage — "Only marriage between a man and a woman shall be valid or recognized in Nebraska. The uniting of two persons of the same sex in a civil union, domestic partnership, or other similar same-sex relationship shall not be valid or recognized in Nebraska." — is unconstitutional. (See footnote 1 of the decision.) But as I'll discuss below, the logic of the opinion suggests otherwise; if the judge is right, then states would indeed be required to recognize same-sex marriage.

- First Amendment: The judge reasons that the amendment is unconstitutional because it interferes with people's First Amendment rights to advocate, and to association in order to advocate, for legislation protecting same-sex relationships: "The knowledge that any such proposed legislation violates the Nebraska Constitution chills or inhibits advocacy of that legislation, as well as impinging on freedom to join together in pursuit of those ends."

That, I think, can't be right. Most state constitutional provisions make it harder for people to enact certain laws — a state constitutional right to privacy, for instance, makes "chills or inhibits advocacy of [privacy-restricting] legislation" in precisely the same way as the Nebraska same-sex amendment does: People become less willing to advocate the legislation since they know it will be futile, so long as the amendment remains on the book. Likewise, federal laws "chill[] or inhibit[] advocacy of [state] legislation" that would be preempted by those laws. State laws "chill[] or inhibit[] advocacy of [local] legislation" that would be preempted by those laws. (For instance, state marriage laws, which to my knowledge always set forth rules that apply throughout the state and leave no room for contrary local decisions, equally chill or inhibit advocacy of city- or county-level marriage laws.)

Of course, none of these laws or constitutional provisions violate the First Amendment; they don't keep people from expressing their ideas — they just make it harder for people to turn those ideas into law. That is the very purpose of constitutional constraints on legislation, and the purpose doesn't violate the First Amendment. But precisely the same is true about the Nebraska same-sex marriage amendment.

- Intimate association: The Supreme Court has recognized that people have an unenumerated right to engage in intimate association — to make friends, to rear children, to live with relatives, and the like. The judge in this case argued that the Nebraska provision interfered with this right:

The amendment goes far beyond merely defining marriage as between a man and a woman. By its terms, Section 29 mandates that Nebraska will not recognize or give effect to “the uniting of two persons” in a same-sex relationship “similar to” marriage. This language, especially given the expansive reading it has been afforded in Nebraska, potentially prohibits or at least inhibits people, regardless of sexual preference, from entering into numerous relationships or living arrangements that could be interpreted as a same-sex relationship “similar to” marriage.

I'm not sure that the court is reading the amendment properly: Living together and sharing expenses (or even ownership of property) is not necessarily "the uniting of two persons of the same sex in a civil union, domestic partnership, or other similar same-sex relationship" — the only legal relationships there are those of co-owners, which have never been seen as "civil unions," "domestic partnerships," or "same-sex relationships." (The matter might be somewhat different as to shared custody of children.)Many social or associational arrangements run the risk of running afoul of the broad prohibitions of Section 29. Among the threatened relationships would be those of roommates, co-tenants, foster parents, and related people who share living arrangements, expenses, custody of children, or ownership of property.

But in any event, the amendment does not prohibit any cohabitation relationships — at most, it bars the government from giving them legal recognition as a "civil union," "domestic partnership," or "same-sex relationship." The right to intimate association does not include the right to have the government specially subsidize or recognize your intimate association. That's why, for instance, the law can give married people special benefits that single people lack. Your intimate association rights doubtless give you the constitutional right not to get married, but that doesn't mean the government has to give you as a single person the same subsidies and special legal privileges that it gives married people. (I will deal with the equality argument below, but for now my point is simply that there's no violation of intimate association rights here.)

The amendment might conceivably bar same-sex couples, as couples, from adopting children or having foster children. But the constitutional right to intimate association does not include the right to adopt or to have foster children.

- Equal protection: The court holds that the Nebraska amendment violates the Equal Protection Clause, citing Romer v. Evans (1996). Here, it's argument is at least plausible: Romer struck down a Colorado amendment that prohibited all state and local bans on sexual orientation discrimination. I think Romer is wrong, badly reasoned, and vague in its implications; but, while it's impossible to tell for sure given Romer's vagueness, I think that Nebraska amendment is constitutional even under Romer.

Romer rested in large part on the conclusion that the Colorado amendment's "sheer breadth is so discontinuous with the reasons offered for it that the amendment seems inexplicable by anything but animus toward the class that it affects; it lacks a rational relationship to legitimate state interests." The Colorado amendment's defenders urged that the amendment was needed to protect "other citizens' freedom of association, and in particular the liberties of landlords or employers who have personal or religious objections to homosexuality"; and the Court did not condemn this interest. Rather, it concluded that "The breadth of the Amendment is so far removed from these particular justifications that we find it impossible to credit them," chiefly because the Colorado courts interpreted the amendment as being extremely broad, covering many situations where no private landlords or employers were involved (for instance, when the government created a nondiscrimination policy governing its own operations).

Here, the law leaves state and local government free to enact bans on sexual orientation discrimination in lots of contexts. The government only mandates that marriage and similar institutions be reserved for opposite-sex couples; and this mandate is closely tied to the government's desire to reserve the special benefits of marriage for that sort of relationship — a union of one man and one woman — that Nebraskans think is particularly valuable to society, and thus particularly worth fostering.

The test that Romer set forth was that the law must have a rational relationship to legitimate state interests, not the very demanding "strict scrutiny" test (which requires narrow tailoring to compelling state interests). This "rational basis" test is traditionally pretty deferential to the government; and while in Romer it wasn't applied with the normal deference, the Court's stress in Romer was simply that the law was so overinclusive relative to the interest in protecting associational freedom that it was irrationally broad. Here, the law is a much better fit with the government interest. And it seems to me (and, I'd wager, to the Supreme Court) that the government interest in promoting opposite-sex relationships as the best for society is indeed a legitimate interest, even if it's one that reasonable minds may differ about.

Nor is it right to argue, as the court does, that the law "goes so far beyond defining marriage that the court can only conclude that the intent and purpose of the amendment is based on animus against [the] class [it affects]." First, the law doesn't go at all far beyond defining marriage; it clearly covers marriage and its modern equivalents and near-equivalents. It makes perfect sense that as new quasi-marriage statuses are set up to avoid the legal restrictions on marriage, voters would cover these quasi-marriages as well as traditional marriages.

Second, while the law does reflect a sense that same-sex unions are less worthy of public support than opposite-sex unions, the Court has never held that this view is impermissible. Most laws reflect the notion that some conduct is better than other conduct. Unless (and I'll get to this below) the court really is saying that it's unconstitutional "animus" to have marriage be opposite-sex-only — that is to say, unless the court believes that Nebraska has to recognize same-sex marriages — there's no unconstitutional animus in Nebraska voters' insisting that marriage be opposite-sex-only, rather than just leaving the matter to their representatives in the legislature.

Finally, note that the standard canon of interpreting statutes is that they must be interpreted to avoid constitutional problems, when such an interpretation is consistent with the language. For instance, if the court fears that reading the amendment broadly — for instance, covering co-tenancy contracts, or co-ownership arrangements, among romantically linked same-sex couples — would violate the Equal Protection Clause under Romer, then the court should read the amendment (quite plausibly) as not being that broad, and only covering marriages, statutory civil unions, or statutory domestic partnerships, not centuries-old generally applicable rules of contract and property law.

Judges should not choose the broadest interpretation of a statute and then strike the statute down because the interpretation they themselves chose was unconstitutionally broad. Thus, the judge's argument that "a domestic limited partnership" — a business entity — "composed of same-sex partners as defined in the Partnership Act could run afoul of [the Nebraska amendment] as it is written" is quite wrong. Reading the amendment as covering business partnerships that just happen to have partners of the same sex isn't even a particularly plausible reading of the amendment; and it certainly isn't the only or most plausible reading of the amendment. The judge must therefore choose the reading that is constitutionally permissible under Romer, rather than choosing an unnecessarily broad reading that would then lead him to strike the statute down.

- Bill of Attainder Clause: The court also reasons that the law is an unconstitutional bill of attainder because it "inflict[s] punishment" on same-sex couples, because it's "directed at gay, lesbian, bisexual and transsexual people and is intended to prohibit their political ability to effectuate changes opposed by the majority." That's quite mistaken, I think, for the reasons I mentioned as to the First Amendment — all state constitutional provisions, as well as federal laws that preempt state laws and state laws that preempt local laws, block some groups from enacting laws that they like.

State constitutional bans on polygamy block polygamists from enacting laws that they like. State bans on lotteries block lottery operators from enacting laws that they like. Some state criminal rights provisions block some tough-on-crime folks from enacting laws that they like.

Moreover, it's the nature of a democracy that the majority blocks "changes opposed by the majority." It may not block advocacy for such changes; but it can surely block such changes. And if the majority sufficiently opposes certain changes, it can block them at the state constitutional level rather than just at a state statutory level, or at a state statutory level rather than the local level. The whole point of state constitutions is for the statewide majority to prevent its representatives in the legislature (or voters or legislators in the state's political subunits) from enacting changes opposed by that statewide majority.

The prohibition on Bills of Attainder provision has never been read remotely as broadly as the court suggests; nor would it make any sense for it to be read this broadly.

- But in any event — and here I return to what I said in point 1 — if the court is right about the Romer analysis, then it must be because there is no legitimate government interest in favoring opposite-sex long-term relationships over same-sex ones. Likewise, if the court is right about the intimate association analysis, then it must be because the right to intimate association guarantees same-sex couples the right to equal government benefits with opposite-sex married couples, rather than just a right to live together. And if the court is right about bills of attainder, then its analysis equally applies to state law rules that preempt contrary marriage provisions at the city level. (Imagine Portland or San Francisco trying to set up its own marriage rules, over the objections of the rest of Oregon or California.) And if that's so, then despite the court's protestations, its reasoning necessarily means that states are constitutionally required to recognize same-sex marriage (or, under the bill of attainder analysis, at least are required to let any locality recognize same-sex marriage).

So this isn't just a battle over state constitutional amendments, and what voters can do and what they must leave to the state legislature. The court's decision, if upheld, would be a Massachusetts Goodridge (or at least its Vermont civil-union cousin, Baker) for the whole nation. I don't think this is at all required by Romer, Lawrence v. Texas, or any other Supreme Court decision. I'm pretty sure that the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals will reverse the decision; and if it doesn't, I'm pretty sure that the U.S. Supreme Court will — and should.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Federal Court Strikes Down Ban on Same-Sex Marriage:

- Quick, Someone Call Tom DeLay:

As best I can tell from a very quick scan of the opinion, Judge Bataillon's opinion holds that the Nebraska ban on same-sex marriage violated a slew of constitutional doctrines. Those doctrines include: 1) "the right to associational freedom protected by the First Amendment and the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, 2)"the right to petition the government for redress of grievances, which encompasses the right to participate in the political process," 3) equal protection the laws pursuant to Romer v. Evans, and 4) the prohibition against Bills of Attainder under Article I, Section 9. Notably, there is hardly any mention in the opinion of Lawrence v. Texas.

I have enabled comments. As always, civil and respectful comments only. (Hat tip: How Appealing, of course.)

Related Posts (on one page):

- Federal Court Strikes Down Ban on Same-Sex Marriage:

- Quick, Someone Call Tom DeLay:

A team of geneticists believe they have shed light on many aspects of how modern humans emigrated from Africa by analyzing the DNA of the Orang Asli, the original inhabitants of Malaysia. Because the Orang Asli appear to be directly descended from the first emigrants from Africa, they have provided valuable new clues about that momentous event in early human history.

The geneticists conclude that there was only one migration of modern humans out of Africa - that it took a southern route to India, Southeast Asia and Australasia, and consisted of a single band of hunter-gatherers, probably just a few hundred people strong.

Estimated time before a mirror image anti-nominee blog appears on the website of a left-of-center magazine: I'll give it about 72 hours. (Hat tip: How Appealing)

UPDATE: When you're checking out Bench Memos, be sure to read this post by Ramesh Ponnuru on Ken Starr's views of the filibuster. Seems like an important scoop.

Related Posts (on one page):

- More Starr on the Filibuster:

- Blogging Judicial Nominations:

In this brief Foreword to a forthcoming symposium on Lochner v. New York, I ask the question, What's So Wicked About Lochner? Modern Progressives cannot complain about its protection of so-called substantive due process, since they favor just that. Nor can they claim that Lochner violates the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, since these legal analysts by and large reject originalism altogether. This leaves only today's judicial conservatives to adhere to a purified Roosevelt New Deal jurisprudence of disdain for Lochner.My other recent uploads to SSRN are:

My answer is that Lochner is objectionable precisely because its reliance on the Due Process Clause perpetuated the serious misinterpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment established by the 5-4 decision in The Slaughter-House Cases. While Lochner's use of a presumption in favor of the liberty of citizens is basically sound—however well it may have been applied in the actual case—its reliance on the Due Process Clause, rather than on the Privileges or Immunities Clause undermined the legitimacy of its method. I then offer the outline of an approach to Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment that gives a distinct meaning to each of its four Constitution-altering clauses.

Trumping Precedent with Original Meaning: Not as Radical as It Sounds

Why You Should Read My Book Anyhow: A Reply to Trevor Morrison

Grading Justice Kennedy: A Reply to Professor Carpenter

Some originalists deal with the problem of Brown by invoking precedent. Other originalists who, like me, are generally skeptical of precedent (see my essay on originalism and precedent here), cannot go that route (though our approach to originalism would not have any awkwardness rejecting the precedent of Plessy).

Most scholars today know of Michael McConnell's work on school desegregation and originalism, though it seems not to have made much of a dent in the criticism. A concise summary of the originalist response to this repeated charge (including that by Judge McConnell) is presented by Edward Whelan in Brown and Originalism: There’s more than one way to get it right. Here is how it starts:

The Left's "killer" argument against an originalist reading of the Constitution is that adherence to the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment purportedly would not have yielded the just result — the end to the evil of segregated public schools — mandated by the Supreme Court's landmark 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. Margaret Talbot's interesting but flawed profile of Justice Scalia and originalism in a recent issue of the New Yorker (which I wrote about here) is typical: The only "way to get to Brown," she asserts, is "to embrace the 'living Constitution.'"In my experience, scholars who are not originalists typically do not do originalist analysis very well. In part, this may be because they are attempting by their historical analysis to discredit originalism or at least neutralize an originalist outcome with which they disagree. Perhaps the biggest problem is that, not being originalists, they are not altogether careful about what an originalist argument entails—especially as original intent originalism has been largely abandoned in favor of original meaning originalism. (This may partially account for the Court in Brown finding the historical evidence inconclusive.) Whelan ends his essay on a similar note:

The legitimacy of originalism as the only proper method (or class of methods) of constitutional interpretation inheres in the very nature of the Constitution as law and does not depend on the results that originalism yields. Originalists will have disputes among themselves. But those who seek to discredit originalism by hiding behind Brown . . . should hardly be presumed sound arbiters of how originalism should apply.This essay makes a good introduction for law students about to take constitutional law, but students should definitely read Michael McConnell's articles as well:

Originalism and the Desegregation Decisions, 81 Virginia Law Review 947 (1995) and[Both are on Westlaw and Lexis, of course, but if someone sends me on-line links to these article, I will add them to this post later.]

The Originalist Justification for Brown: A Reply to Professor Klarman, 81 Virginia Law Review 1937 (1995).

Update:Those with a heinonline subscription can click here for the McConnell article.

A very good piece by my fellow Russkie, Max Boot.

here. I'm not sure I agree with everything Cramer says here, but the criticisms of Buchanan strike me as quite apt.

The Brady Campaign, the largest of the gun prohibition lobbies, is holding a press conference today to "discuss how police officer's jobs have become more dangerous since assault weapons with large capacity clips are more readily available." There's good reason to be skeptical about whatever claims the group will make. First of all, there are not many guns which actually use "clips" to store their ammunition. The venerable M-1 Garand from World War II used clips, but most guns of the last half-century store their ammunition in "magazines."

And of course, the Brady Campaign's definition of "assault weapon" is almost infinitely elastic; the "assault weapon" bill which the group successfully pushed in New Jersey even banned some BB guns.

The group's definition of "large" capacity magazines is also extreme. The now-expired 1994 federal gun ban defined "large" as anything over 10 rounds, even through millions of ordinary self-loading guns have a standard magazine capacity of 13-17 rounds. Notably, the group (under its previous name of "Handgun Control, Inc.") testified before the New York City Council in favor of banning any magazine holding more than 6 rounds.

What about the group's mantra that "large" magazines endanger police officers? The group made a similar claim in 1995; as I detailed in an article in Law Enforcement Trainer, the data from the study turned out to be misleading. In truth, so-called "assault weapons" with "large" magazines are very rarely used in crimes of any sort, including crimes against police officers.

Tony Mauro has an interesting article on whether the number and tone of Supreme Court questions can tip off the final result in the case:

In a new study entitled "The Illusion of Devil's Advocacy: How the Justices of the Supreme Court Foreshadow their Decisions During Oral Argument," Sarah Shullman came up with a surprisingly simple and accurate way of predicting outcomes based on the number and tenor of oral argument questions by justices.Shullman's article, in The Journal of Appellate Practice and Process, reports on oral arguments in 10 cases she observed during the October 2002 term. As she watched, she tallied the number and tenor — helpful or hostile — of all the questions asked by all the justices. Then a student at Georgetown University Law Center, Shullman is now an associate at Steel Hector & Davis in West Palm Beach, Fla.

After seven of the 10 cases she studied were decided, Shullman looked for correlations — and found them. In all of the cases, the justices in aggregate asked more questions, and more hostile questions, of the party that ultimately lost the case. The model of the devil's advocate — peppering the side you favor with tough questions — did not appear prevalent enough to derail this conclusion. . . .

In any event, on the basis of her early success, Shullman proceeded to predict the remaining three cases she had charted that were still pending before the high court. And bingo! She was correct each time. A couple of justices strayed and asked more questions of the side they ultimately favored, but overall the justices turned out to be "quite predictable," she says. . . .

Shullman acknowledges that her sample was small, but the methodology has already been tested since she did her study. John Roberts Jr., one of the masters of the trade before taking the bench in 2003, used her theory for a talk he gave on oral advocacy before the Supreme Court Historical Society last year. Picking 14 oral arguments from the 1980 term and 14 from the 2003 term, Roberts found that in fact the most questions went to the losing party in 24 of the 28 cases — an 86 percent rate of accuracy.

"The secret to successful advocacy," Roberts deadpanned in conclusion, "is simply to get the Court to ask your opponent more questions."

An 86 percent success rate in making predictions compares favorably with that of other players in the growing field of Supreme Court prognosticators. Political scientists have gotten into the game to test the relative importance of precedents and politics in Supreme Court decision making. The Supreme Court Forecasting Project, based at Washington University in St. Louis, used statistical models and a panel of experts to predict the results in the cases argued in the 2002 term. The statistical method, based on data such as the circuit of origin and an analysis of precedents, came out right 75 percent of the time, while the human experts predicted outcomes correctly in 59 percent of the cases.

At a symposium on the project, Linda Greenhouse of The New York Times got into the spirit of things and looked back at her stories from the same term and found that in the 16 decided cases in which she ventured a prediction, she was right 75 percent of the time.

It's not surprising that this might be so, but the numbers in the small-scale studies being discussed were stronger than I would have thought. The story didn't indicate whether any significance tests were done on the data, and without the exact baseline on the % of reversals of the lower court for these cases, I couldn't do the statistics myself.

I went back and roughly counted the number of questions in Raich, the marijuana Commerce Clause case that Randy Barnett argued. Randy got MANY more questions than the government, a bad sign for Randy (and the Constitution).

In skimming the transcript in Raich, at pages 40-41 I also noticed a somewhat playful disagreement between Barnett and Justice Scalia over what "home consumption" of wheat meant in Wickard v. Filburn. Randy said it included wheat consumed by the livestock on the farm; Scalia disagreed, saying it meant wheat eaten by the farmer and his family. I went back and read Wickard. Although there are some ambiguous passages, two passages are clear:

It is urged that under the Commerce Clause of the Constitution, Article I, § 8, clause 3, Congress does not possess the power it has in this instance sought to exercise. The question would merit little consideration since our decision in United States v. Darby, 312 U.S. 100, sustaining the federal power to regulate production of goods for commerce, except for the fact that this Act extends federal regulation to production not intended in any part for commerce but wholly for consumption on the farm. The Act includes a definition of "market" and its derivatives, so that as related to wheat, in addition to its conventional meaning, it also means to dispose of "by feeding (in any form) to poultry or livestock which, or the products of which, are sold, bartered, or exchanged, or to be so disposed of." Hence, marketing quotas not only embrace all that may be sold without penalty but also what may be consumed on the premises.

And this:

had he chosen to cut his excess and cure it or feed it as hay, or to reap and feed it with the head and straw together, no penalty would have been demanded. Such manner of consumption is not uncommon.So Randy is correct on Wickard. Let's hope he is also determined to be correct that the interstate commerce clause applies to "interstate commerce," not intrastate noncommerce.

Reading Wickard, which is a pretty weakly reasoned case by my lights, reminds me that the Supreme Court is in a bind in Raich. Either the Court has to follow the Constitution and strike down federal drug regulation of intrastate noncommercial uses of marijuana (a controversial decision to follow the rule of law), or it has to expand Wickard radically, rendering the Commerce Clause almost (though not quite) a dead letter. Stated another way, the Court either has to expand its federalism jurisprudence slightly (eg, Lopez & Morrison, but in the controversial drug area), or it has to limit Lopez & Morrison to their facts by radically expanding federal power under the Commerce Clause. It can't stand still. Perhaps that is why the Court has been so slow to render an opinion.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Ann Althouse Ponders Raich,--

- Does Asking More Questions Tip the Outcome of Supreme Court Cases?--

Wednesday, May 11, 2005

I'm wondering, has anyone written anything good about the structural and systematic effect of filibustering judicial nominees? Putting aside the question of this president and these nominees, it seems to me that having a de facto 60-vote requirement for confirming appellate judges is an interesting idea. I don't know how it would work or what the scope of it would be, but I'd be interested in reading something thoughtful about its pros and cons. If anyone knows of such a discussion, please provide a citation to it (with the URL or a link if it's online) in the comment section.

UPDATE: A reader asks why I think a 60-vote requirement might be an interesting idea. I'm an outsider to this area, but I imagine the pro-con debate might go something like this:

Pro: A 60-vote requirement is a good idea because we don't want extremist judges. We should have judges with bipartisan support, and a 60-vote requirement ensures that.Something like that, anyway.

Con: You're being naive. You're assuming that the minority party will act in good faith, only blocking judges that they think are "extremist." In reality, minority parties will just block judges they don't like.

Pro: How can the minority party only block judges they don't like? They won't like any of the opposing party's nominees. They'll have to pick and choose which judges to filibuster, and they'll pick the most extreme nominees.

Con: But that will only create an incentive for the President to nominate more "extreme" nominees, whatever that means. If the minority can only stop a few, the President will name a few people knowing that they won't get confirmed.

Pro: Maybe, but political pressures might just prevent that from happening.

Congress barred the government on Tuesday from using any money in a newly passed emergency spending bill to subject anyone in American custody to torture or "cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment" that is forbidden by the Constitution.Over at Balkinization, Marty Lederman takes a look and reaches a somewhat different conclusion:

Proponents said the little-noticed provision, in an $82 billion bill devoted mostly to financing military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, amounted to a significant strengthening of current policies and practices in the treatment of prisoners.

Unfortunately, this new measure is not what it seems. It is extremely well-intentioned, and it might "send a signal" of sorts — but it does not remove the loophole that permits the CIA to engage in conscience-shocking treatment of aliens overseas, which is no doubt why the Administration is more than happy to have the President sign it.

If you're a law student with a blog, you're probably wondering how much you'll be able to say about your job on your blog. No? Well, I am. And since my class in "professional responsibility" didn't address blogging at all (I can't imagine why), I'd love to hear from lawyers, other law students, professors, whomever, about the ethics and boundaries of blawgging a summer job.

The Bar exam draws heavily from Ronald Dworkin, who argues that there are indeed answers to even the thorniest legal issues. Departing from H.L.A. Hart’s open texture of law, where there are pockets of uncertainty, for Dworkin, there is an answer to all legal questions. And so, too, on the Bar. Every question has an answer.I wondered about that when I studied for the bar exam, too. The answer: generally accepted among people who work at BarBri.

The Bar states that one is to choose the best answer, and thus it does at least recognize that right-versus-wrong is too simplistic a way to understand the law. But what does "best answer" mean? The exam states that all questions should be answered "according to the generally accepted view, except where otherwise noted." We’re back to Hart again, with a kind of rule-of-recognition for the rules on the Bar: The best answer is the generally accepted view. But among whom? Lawyers? Judges? Academics? The public? The Bar doesn’t tell us.

Rita Kirk, the department chairwoman, says that she received complaints about the blog from students and parents, and that she consulted with university lawyers about what to do about it. Kirk describes herself as a strong First Amendment supporter, but she says she worries that the blog violated students’ privacy rights and upset some students. "People need to remember that words can hurt," Kirk says.Hat tip: David Greenberg.

UPDATE: Oh, crud. My only marginally funny punch line doesn't work because it turns out that the conference was actually last weekend, not this coming weekend. As they always say -- when it comes to humor, timing is everything.

Tuesday, May 10, 2005

Who do you think is the best Supreme Court advocate in the last 30 years, at least according to Justice Stevens?

a) Seth Waxman

b) John Roberts

c) Laurence Tribe

d) Robert Bork

e) Walter Dellinger

Hillsborough High School in Tampa earned a D grade from the state last year. And under federal standards, it fell far short.

But on Monday, Newsweek magazine named it the 10th best high school in the country.

In the country.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Newsweek's Top 10 High School Gets A "D" From the State:

- I Suppose Newsweek Can Sell Magazines, Too:

The most controversial aspect of the Real ID act seems to be the list of items that a driver's license must have:

(1) The person's full legal name.In particular, the controversial provisions are (6) and (9). Element (6) apparently would require driver's licenses to contain actual addresses, instead of P.O. Boxes or other mail drops, and (9) would apparently require that cards retain data much like your credit card retains its number, so driver's licenses could be "swiped" instead of manually checked.

(2) The person's date of birth.

(3) The person's gender.

(4) The person's driver's license or identification card number.

(5) A digital photograph of the person.

(6) The person's address of principle residence.

(7) The person's signature.

(8) Physical security features designed to prevent tampering, counterfeiting, or duplication of the document for fraudulent purposes.

(9) A common machine-readable technology, with defined minimum data elements.

Specifically, here are Schneier's three primary arguments against the Real ID Act:

[Element (9)] will, of course, make identity theft easier. Assume that this information will be collected by bars and other businesses, and that it will be resold to companies like ChoicePoint and Acxiom.But why should we assume that? If a bar or other business told me that I had to let them swipe my license to buy something or enter the store, I would go elsewhere. I imagine most other people feel the same way. Perhaps making the information more easily accessible would change information collecting practices, but that's a case that has to be made. (I recognize that invoking ChoicePoint is a good scare tactic, but I would be interested in a careful analysis of why Schneier thinks ID cards would be used this way rather than his inistence that we should just assume it.)

Even worse, the same specification for RFID chips embedded in passports includes details about embedding RFID chips in driver's licenses. I expect the federal government will require states to do this, with all of the associated security problems (e.g., surreptitious access).The problem is the law doesn't require the use of RFID. The fact that RFID could be used in lieu of a swipe card doesn't mean that it would have to be used, and I imagine most people would much prefer the use of a familiar swipe card instead of RFID. Schenier doesn't explain why he expects RFID would be used.

REAL ID requires that driver's licenses contain actual addresses, and no post office boxes. There are no exceptions made for judges or police — even undercover police officers. This seems like a major unnecessary security risk.I appreciate Schneier's concern for our nation's judges and police officers, but I don't understand the source of it. Undercover police officers don't carry around their real IDs anyway, and if they do it's a police badge, not a driver's license. And I'm unaware of judges or police officers as a whole being concerned about the security risks of having their home addresses on their licenses. (I would imagine that the overwhelming majority have their home addresses on their licenses now.)

As I said up front, I am tentatively against the Act. I agree with Dan Solove that it should be debated carefully, not passed as a rider on a military spending bill. But if there is a slam dunk case against the Act, I don't think Bruce Schneier has made it.

I'm not sure if this is something readers will want to comment on, but I'll enable comments just in case.

Legal Affairs editor Lincoln Caplan had this article on judicial independence in Sunday's Washington Post "Outlook" section. I like Caplan's magazine, but I can't say the same for his essay.

The article is filled with contradictions. For instance, Caplan writes:

the legal right is increasingly divided between those who practice what the politicians preach and others keen to pursue their own agendas through the courts. Some, like Stanley Birch, adhere to traditional concepts of judicial restraint. Others, including Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, in the name of applying what they regard as the original intent of the Constitution's framers, have no compunction about aggressively striking down acts of Congress in ways that conservatives once called activist.Now there are certainly divisions on the right between those who favor more or less aggressive judicial review. But Caplan's comparison does not work because his example of Judge Birch's "judicial restraint" is striking down a federal statute. If Caplan wants to distinguish the Birches from the Scalias and Thomases, he'll have to do better than that.

While Caplan, at times, seems to praise judicial restraint, he still wants judges who will strike down federal laws when necessary. In other words, Caplan has an implicit theory about when it is or is not appropriate to strike down statutes, but it remains unspoken. Instead he hides behind notions of "independence" and "impartiality."

Caplan defends the Democratic filibuster of judicial nominees to ensure the "impartiality" of judges. Yet how is it "impartial" to demand judicial nominees commit to certain positions on key issues, as some Senators have done? How is it "impartial" to impose litmus tests on key issues (e.g. abortion)?

There are many ways to describe the sorts of judges that Senate Democrats (and Caplan) would prefer, but "impartial" hardly seems the right word. Setting aside the proper approach to judicial review, striking down federal statutes supported by popular majorities on bases other than explicit constitutional text may well be justified in certain circumstances, but this would hardly be described as an "impartial" approach to judicial review. Whatever the merits of judicial deference to legislative decisions, this would seem to be less "partial" than aggressively striking down federal statutes.

Finally, Caplan says "the current Supreme Court has a right and a center, but no left." This is just silly. If it were the case we would see more decisions overturning Warren and Burger Court precedents and fewer cases that, like Lawrence and Roper, shift constitutional jurisprudence to the left. Any description of judicial ideology along these lines must account for the trajectory of the Court's doctrines, many of which, I would submit, still trend left. (I'll have more on this in a subsequent post.)

There's more, such as Caplan's strained treatment of the so-called "Constitution in Exile" movement, but I'll leave it at that. For further critiques of Caplan's essay, see these comments by Ramesh Ponnuru and Paul Mirengoff.

Congratulations to Betsy of BetsysPage, who teaches (or has taught) AP US History and AP Government at the Raleigh Charter School. In Newsweek, her school placed 9th among public high schools choosing less than half of their students with grades or other entry credentials.

I wish that I had had a teacher like Betsy when I was in High School.

Her students are very fortunate.

Like a stern father figure, Atty. Gen. Alberto R. Gonzales warned Los Angeles high school students last month about the perils of illegally downloading music or movies.

"There are consequences," he said. "It is unlawful."

Backing up the threat is another matter. While federal prosecutors have made fighting piracy a top priority, to date they have been reluctant to go after the group the entertainment industry most wants targeted: people who illegally download from hugely popular online file-sharing networks.

"No U.S. attorney wants to be the guy who put a UCLA sophomore in jail for downloading Britney Spears," said George Washington University law professor Orin Kerr, a former federal high-tech crimes specialist.

Monday, May 9, 2005

That's the suggestion of Posse Incitatus, which notes the result of a state-federal-local dragnet which rounded up over 10,000 fugitives. Only two percent of these fugitives had guns. P.I. suggests that the data show that American gun control laws work so well that criminals are much less likely to own guns than is the general public.

That's a good point, regarding fugitives who were arrested in their homes, presuming that many arrests included the lawfully-allowed "protective sweep" by police officers to check the vicinity for weapons. As for the arrests that took place in public areas, a gun carrying rate of two percent might not be far different from the rates of lawful carrying by licensed citizens.

President Bush's top political and legal advisers have been quietly planning for the possibility that two Supreme Court justices will step down from the bench at the end of this term, the DRUDGE REPORT has learned.Of course, planning alone doesn't mean much; Presidents have been planning for an opening in the current Court since Breyer arrived in 1994.

"Plan for two," the president recently told senior staff, sources claim.

An aside: I wonder, what role will the legal blogs play in the debate over future Supreme Court nominees? A big one, I would think. The merits of nominee X will be the topic of the month, and the debate will be much faster, more sophisticated, and more widely read by legal insiders than anything in the MSM.

UPDATE: Tom Goldstein offers some very helpful thoughts here. For what it's worth, I'm with Tom that it's highly unlikely that any of the sitting Associate Justices would be nominated for the Chief position. While Justice O'Connor has mostly been a centrist during her time on the Court, these days she breaks left more often than she breaks right; it's hard to imagine the White House considering her. Kennedy breaks left in the politically-important culture-war cases, so he's out. Scalia and Thomas are rock-solid conservatives, but they're among the least skilled tacticians on the Court; not great Chief material. Given that, look for the White House to nominate an outsider.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Newsweek's Top 10 High School Gets A "D" From the State:

- I Suppose Newsweek Can Sell Magazines, Too:

Tom's thoughts on his blog are always worth reading. Today, for example, he touts an excellent film with very libertarian themes: The Jack Bull. I strongly recommend adding TomGPalmer.com to your list of frequently surveyed blogs.

When the Huffington Post was first announced, I noted that, while people were focusing on the celebrity group blog, the Drudge-like news service might be the most important driver of eyeballs:

Aha! So someone who is not well known (or, more precisely, is about as well known as a lot of prominent non-celebrity bloggers), Andrew Breitbart, may be writing a news service to compete with Drudge. That is at least a plausible hook--someone with web expertise but without a famous name might provide important content.

Glancing through the debut edition of the Huffington Post, the news service seems to be a big part of the affair.

More comments from Howard Kurtz and Reynolds.

Nikki Finke has a negative review of the Huffington blog, and suggests that its financing might be shakier than is widely known.

In order to build readers' confidence, an internal committee at The New York Times has recommended taking a variety of steps, including having senior editors write more regularly about the workings of the paper, tracking errors in a systematic way and responding more assertively to the paper's critics.The 16-page report will be posted here sometime Monday during the day.

The committee also recommended that the paper "increase our coverage of religion in America" and "cover the country in a fuller way," with more reporting from rural areas and of a broader array of cultural and lifestyle issues.

UPDATE: Former Wilmer associate Michael Froomkin offers some thoughts on Cutler here.