|

Saturday, March 11, 2006

Does Mexican immigration reduce crime?

Robert Sampson writes in today's NYT Op-Ed page:

...evidence points to increased immigration as a major factor associated with the lower crime rate of the 1990's (and its recent leveling off).

Hispanic Americans do better on a range of various social indicators -- including propensity to violence -- than one would expect given their socioeconomic disadvantages. My colleagues and I have completed a study in which we examined 8,000 Chicago residents who were asked about the characteristics of their neighborhoods.

Surprisingly, we found a significantly lower rate of violence among Mexican-Americans than among blacks and whites...Indeed, the first-generation immigrants (those born outside the United States) in our study were 45 percent less likely to commit violence than were third-generation Americans, adjusting for family and neighborhood background. [TC: But don't absolute probabilities play the key role here? And should we compare Mexicans to "blacks and whites" or to each group in isolation?] Second-generation immigrants were 22 percent less likely to commit violence than the third generation.

Our study further showed that living in a neighborhood of concentrated immigrants is directly associated with lower violence (again, after taking into account a host of factors...)

Alas, there is no permalink these days. Here is the relevant project which generated the data. No one of Sampson's pieces on his web page seems to cover this result, though many are relevant more broadly. Also see this summary of his criticism of "broken window" and "tipping point" theories of crime.

Here is another piece which seems to support the basic result that Mexican immigration lowers crime. Here is a survey article on the topic. This piece (see p.113) suggests that crime is lower in border cities than comparable non-border cities, and that Mexican immigration cannot be identified as a cause of a higher U.S. crime rate.

Yes comments are open, but purely anecdotal accounts of how you were once mugged by a Mexican, or how your neighborhood just isn't "the same anymore" are discouraged. I'm posting a version of this over at MarginalRevolution.com as well, look for the differing comments.

What Was Saddam Thinking?:

Tomorrow's New York Times has a fascinating story on Saddam Hussein's strategy leading up to the Iraq war. According to the account, Saddam was worried more about internal unrest than a U.S. invasion; he believed that the U.S. would never risk the casualties that would result from a ground war. Further, Saddam wanted the world to suspect he had WMDs as a deterrent; in particular, he didn't want enemies like Iran to know that he was vulnerable.

Friday, March 10, 2006

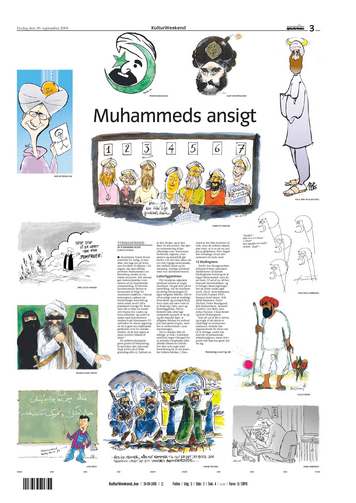

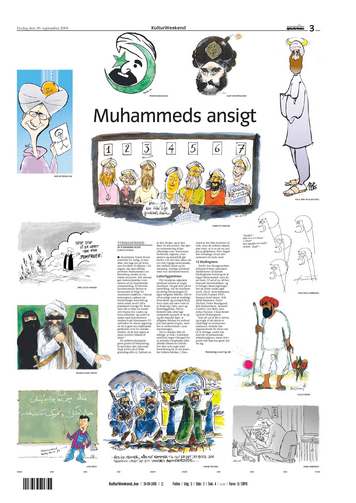

The Twelve Mohammed Cartoons, in Detail:

One shocking thing about the Mohammed cartoon controversy is how tame many of the cartoons are — and therefore just how much the cartoons' critics are demanding by arguing that the cartoons ought not be published, or even ought to be outlawed. Here's the dirty dozen, with thanks to Wikipedia:

Bigger images, including translated captions, are available here.

(1) The cartoons depict Mohammed, which some Muslims claim is prohibited by Islam (though historically a good deal of Islamic art has depicted Mohammed; the Islamic world has hardly unanimous on this). Fair enough: If you're a Muslim, presumably you can't do this. But to demand that non-Muslims comply with Islamic law is a mighty big demand, much like Orthodox Jews demanding that none of us write the word "God." Thanks, but no thanks: Your sense of what your religion demands doesn't create any obligation, whether legal or moral, on me to go along with your preferences.

(2) Some of the cartoons are actually pretty interesting artistically, at least to this observer; the image of Mohammed merged with the green star and crescent, for instance, seems to me an interesting and ingenious composition. The picture of Mohammed in the desert works for me because it humanizes the character, portraying him as a man and not just a symbol.

(3) Some of the cartoons have no criticism of Mohammed, of Islam, or of Muslims at all; two (the young schoolteacher and the "PR stunt" one) criticize the newspaper.

(4) Some of the cartoons are political commentaries that are pretty clearly criticisms of some strands of modern Islamic culture, but not of Islam generally. The cartoon in which Mohammed is waving off two angry Muslim warriors by saying "Relax guys, it’s just a drawing made by some infidel South Jutlander," is a message that true Islam (the teachings of Mohammed) counsels against what some extremist Muslims do in Mohammed's name. The cartoon in which the cartoonist is drawing Mohammed while looking nervously over his shoulder points out — entirely correctly, as we've learned — that drawing Mohammed is a perilous activity.

(5) Finally, some of the cartoons are indeed cast as criticisms of Islam generally, or of Mohammed generally. The display with the crescents, stars, and Stars of David apparently reads "Prophet, daft and dumb, keeping woman under thumb." Another cartoon depicts Mohammed with a bomb in his turban. Another shows Mohammed telling suicide bombers "Stop, stop, we have run out of virgins!" (referring to the supposed heavenly reward for martyrs) which suggests that Mohammed would endorse the killing of innocents that is modern Muslim suicide bombers' stock in trade. The cartoon that shows a fierce-looking Mohammed with a knife and two veiled women in the background likewise seems like a criticism of Mohammed. (The lineup with Mohammed, Jesus, Buddha, and others strikes me as more a joke than a criticism of the portrayed figures.)

These latter items are ones that I as an editor probably would not have published, because I think they're not entirely fair. The ones that allude to Muslim violence tar Muslims generally with the sins of particular subgroups of Muslims. The criticism of Muslim treatment of women may be more broadly accurate of a wide range of religious Islamic thought and practice (though not by any means all religious Islamic thought and practice), but seems rhetorically excessive.

Yet these sorts of overgeneralizations and rhetorical excesses aimed at historical or religious figures as symbols for a movement are an inevitable part of free debate about ideas. This is especially so for cartoons, slogans, and jokes, which because of their conciseness will almost always oversimplify. It is also so because many of these images are necessarily ambiguous. I do not, for instance, understand the Mohammed with the bomb in his turban as accusing Islam generally; it seems to me to be a condemnation of one particular aspect of Islam — militant Islam that often centers on murderous violence against those it sees as its enemies. Again, as an editor I would probably have avoided items with this sort of ambiguity; but it is perfectly understandable that other editors would have a different view. To the extent there is a transgression of editorial judgment or good manners here, it is a relatively minor one.

Of course I realize that some disagree, and see any even possibly pejorative reference to Mohammed — or for that matter any depiction of Mohammed — as a horrible emotional injury. But their subjective feelings, real as they may be to them, are not sufficient reasons for the rest of us to change the way we talk or write. "I'm offended" cannot be justification enough, either in law or in manners, for the conclusion "therefore you must shut up." (Among other things, note that many people are quite understandably offended when others say "I'm offended, therefore you must shut up." If mere offense on some listeners' part is reason enough for the speakers to stop saying, then I take it that those who are offended have an obligation to themselves remain silent.)

This is why this issue is so important: Those who demand that the cartoons not be published or republished are cutting at the heart of public debate. They are either demanding that some ideologies not be criticized, or that they be handled with such kid gloves that normal debate about them — which is inevitably impassioned, given the magnitude of the issues involved — is practically impossible. This is why the West must resist this pressure to silence, both as a legal matter and as a matter of editorial judgment.

"EU-Ministers Considering Arab Demands":

Agora reports, translating today's Jyllands-Posten article from Danish (if you speak Danish and either agree or disagree with the translation, please let me know): EU-Ministers considering Arab demands

It may no longer be enough to just combat discrimination, a presentation document at meeting of EU-ministers says.

As a pendant to the Muhammed-affair, the Foreign Ministers of the EU are considering complying with Arab demands to “fight defamation of religion.”

So far the EU has voted against these kinds of proposals at meetings of the UN General Assembly, but they are now considering reversing that. So a written presentation document aiming at bettering the relations between Europe and the Islamic countries.

- It raises the question of whether, considering recent events, we should reconsider the EU’s approach to these matters at the UN General Assembly, the document says.

The Islamic Conference, the OIC and the Arab League have demanded guarantees that the Muhammed-affair will not be repeated. The site also offers a transcript of an interview with EU Foreign Commissioner Benita Ferroro Waldner: Commentator: Why couldn’t you just put the Muhammed-affair to rest?

BFW: Because I don’t think this was a sporadic incidence. I think it was the peak of an iceberg, if you want. It showed a frustration among Moslems. And I think what we have to do is really engage with them, clearly speaking up about our fundamentals but also see where is, so to say, the border of that, the limit of that. And I think the limit of our Freedom of Speech is there where, indeed, the freedom of “the other” starts and where we have to show a responsibility and a respect and also tolerance for each other. But I also see it as a two-way street.

As I've said before, this is an argument for appeasement and surrender, surrender of one of the most basic of Western Enlightenment principles: that ideas, even deeply and dearly held ones, must be open to constant challenge and criticism (including criticism that will inevitably be overheated and at times even rude). Yes, the West, and in recent years especially Western Europe, have retreated from this principle, at times advocacy of Nazism, advocacy of racism, criticism of homosexuality, and even blasphemy. But this in no reason to ignore yet another retreat, especially a retreat as significant as the one that some in Europe seem to be counseling — significant precisely because much in Islamic theology, culture, and politics (and no doubt much in Christian, Hindu, atheist, etc. theology, culture, and politics) needs to be challenged and criticized.

I certainly hope that Europe resists these recommendations, which are dangerous precisely because they come now from inside and not just from outside. I wonder, though, whether it will.

Related Posts (on one page): - "EU-Ministers Considering Arab Demands":

- Let's Give the Muslim World a Message:

Patriot Act Audits and Article II Powers:

In his signing statements for the Patriot Act reauthorization, President Bush included the following statement: The executive branch shall construe the provisions of H.R. 3199 that call for furnishing information to entities outside the executive branch, such as sections 106A and 119, in a manner consistent with the President's constitutional authority to supervise the unitary executive branch and to withhold information the disclosure of which could impair foreign relations, national security, the deliberative processes of the Executive, or the performance of the Executive's constitutional duties.

The executive branch shall construe section 756(e)(2) of H.R. 3199, which calls for an executive branch official to submit to the Congress recommendations for legislative action, in a manner consistent with the President's constitutional authority to supervise the unitary executive branch and to recommend for the consideration of the Congress such measures as he judges necessary and expedient. By way of background, Section 106A and 199 impose auditing requirement on access to business records and national security letters under FISA. They each require the Inspector General of the Department of Justice to "perform a comprehensive audit of the effectiveness and use, including any improper or illegal use" of these authorities going back to 2002 and then prospectively up for a few years. Section 756(e)(2) is a bit different. It involves a provision of the reauthorization that has nothing to do with terrorism --- it involves grants for programs on how to reduce the use of methamphetamine among pregnant and parenting women offenders. Specifically, the provision requires DOJ to "submit a report to the appropriate committees of jurisdiction that summarizes the results of the evaluations conducted by recipients and recommendations for further legislative action." Generally speaking, executive signing statements such as this have been common in the Bush Administration. Some influential lawyers in the Administration believe that Congress has only limited ability to interfere with the executive branch, and such statements express the Administration's intent not to follow provisions that its lawyers believe interfere with executive power. In most cases, we don't know what the statements mean: the executive branch announces that it is taking a position based on its view of Article II, but never discloses exactly what that position is. I wonder if this case will be a bit different. This isn't my area, so I hope some experts will correct my impression if I'm wrong, but it seems to me that we'll eventually know the executive branch's view in this situation. Congress has required DOJ to conduct audits and file reports, and we'll presumably learn the executive branch's view of the law when it refuses to comply in whole or in part with Congress's requirements. Whether that will lead to a legal challenge to be resolved in court is another matter, of course. Thanks to Marty for the link to the signing statement.

Event Focused on Mohammed Cartoons Happening Friday at UCLA (Not Far from the Law School):

Our local Objectivist club is putting it on: Unveiling the Danish Cartoons: A Discussion of Free Speech and World Response

Misc Event on Friday, March 10, 2006 (7:00pm - 10:00pm)

UCLA Campus: Dodd 147

The Danish cartoons depicting Mohammed have sparked a worldwide controversy. Death threats and violent protests have sent the cartoonists into hiding and have had the intended effect of stifling freedom of expression. The reaction to these cartoons raises urgent questions whose significance goes far beyond a set of drawings.

* What is freedom of speech? Does it include the right to offend?

* What is the significance of the worldwide Islamic reaction to the cartoons?

* How should Western governments have responded to this incident?

* How should the Western media have responded? ...

Please note that the cartoons in question will be displayed at the event....

[Panelists:]

Dr. Yaron Brook is the president and executive director of the Ayn Rand Institute.... He was an assistant professor for seven years at Santa Clara University in Santa Clara, California ....

Kevin James began his professional career as a lawyer, spending three years as an Assistant U.S. Attorney and another ten years as a litigator in high-profile entertainment matters.... [Since 2004, he has been a radio talk show host and a television panelist and commentator.] ...

Avi Davis is a journalist, documentarian, and commentator on Israel, the Middle East, and the Arab world....

Khaleel Mohammed is an Assistant Professor of Religion and a Core Faculty Member of the Center for Islamic and Arabic Studies at San Diego State University. He holds a Ph.D. from McGill University in Islamic Law, and his specialties include Islam, Islamic Law, and Comparative religion....

[Moderator] Dr. Edwin Locke, Dean's Professor Emeritus of Leadership and Motivation at the University of Maryland, has published more than 230 articles, chapters, and books on subjects such as leadership, work motivation, goal setting, job satisfaction, incentives, and the philosophy of science.... Should be an interesting program; I'm sorry that child care duties keep me away from it.

Thursday, March 9, 2006

Update on the ABA's New "Diversity" Standard:

The Michigan Daily has an informative (albeit, as you might expect, rather Michigan-centric) story on the standard, noting criticism by me that the standard is intended to and will have the effect of requiring some law schools [the author says "small"; I tried to get across "resource poor" and "non-elite"] to break the law. The article also contains interesting quotes from Michigan Law School Dean Evan Caminker, who is critical of the ABA's growing tendency to micromanage law schools.

I've heard that many law school deans have become fed up with questionable and expensive policies imposed on them by the ABA, including pressure to tenure law librarians, clinicians, and legal writing professors; pressure to keep even non-"productive" faculty members' teaching loads low; pressure to limit the use of adjuncts; pressure on law schools that have tried their darnedness to attract minority students to spend more and more of their scarce resources on that goal; and so on. If the ABA leadership thinks that the law school establishment is going to rally to its defense on the "diversity" issue, I think it is sadly mistaken. Having abused its accreditation powers for so long in so many ways, there isn't much of a reservoir of support for the ABA to call on.

Relatedly, the ABA's authority to accredit law schools for federal law purposes for is up for renewal at the Department of Education. I learn from John Rosenberg, via the Chronicle of Higher Education, that the Center for Individual Rights, Center for Equal Opportunity (text here), and the National Association of Scholars (text here) have all written to the DOE arguing that unless the ABA is willing to give up its new, illegal diversity rules, reaccreditation should be denied. The Rosenberg link contains some choice quotes.

The Center for Equal Opportunity has also asked the DOE to procure the help of the Justice Department in investigating the ABA for violating federal law.

I'm beginning to think that the ABA has seriously overplayed its hand, and the result may be a weakening of its stranglehold over legal education that goes well-beyond its authority on the "diversity" issue.

David Kris on NSA Surveillance Program:

David Kris, who served as Associate Deputy Attorney General at DOJ from 2000 to 2003 and was one of DOJ's top national security lawyers, has written a 23-page response to the 42-page DOJ memo on the NSA program. Kris, who is now in the private sector, is a terrific lawyer with a very deep knowledge of this area. His memo is (unsurprisingly) very strong. While Kris does not reach a definitive conclusion, the basic thrust of the memo is that the Administration's legal arguments aren't very good. For more on this, see Marty Lederman's post today at Balkinization.

More on the Solomon Amendment case:

My post on Rumsfeld v. FAIR three days ago prompted a thoughtful response from Robert Corn-Revere, a noted First Amendment lawyer, who's more optimistic about the decision than I am. That led to a further exchange between us, hosted by the First Amendment Center. The entire exchange can be read here.

One of the Most Compelling TV Clips I've Seen in a Long Time

is available here; there's also a transcript, though it doesn't really do the video justice (though the video is just talking heads with subtitles).

The program is an interview with Arab-American (but nonreligious) psychologist Wafa Sultan on Al Jazeera (2/21/2006), subtitled by MEMRI TV. I can't say I agree completely with what Dr. Sultan is saying, but I agree with much. And it's extremely important that she's saying it, that she's saying it on Al Jazeera, and that there are people who have the courage to say it given what I suspect is the very serious personal risk that they run.

Thanks to Lance Dakin and to Charlie Eldred for the pointer.

Taxonomy of Legal Blogs:

Ian Best (3L Epiphany) is compiling one, and is looking for input from people about which legal blogs aren't on his list. If you have some ideas, visit his site.

Wednesday, March 8, 2006

I Disagree With What You Say, And I'll Riot If You Say It:

"Muslims Ask French To Cancel 1741 Play by Voltaire", says a Pittsburgh Post-Gazette headline, but the body of the article also suggests that there was more to it than asking: "On the night of the December reading, a small riot broke out involving several dozen people and youths who set fire to a car and garbage cans."

Claiming that a play, even by a great writer, ought not be performed — as a matter of morals and manners, and not as a matter of law — because it's unfair to your group is not inherently troublesome. Some Jews, for instance, have said it as to the Merchant of Venice; I'm not that sympathetic to such objections, but neither do I see much reason to condemn them. But I don't recall any cars being burned on account of the play, or riots involving even a few people, much less several dozen.

As I've noted below, I'm skeptical about attempts to lay the problem at the door of "Islam" (or "Christianity" or "Judaism," as the case may be) in the abstract. But I can say that modern Islamic culture, especially in Europe and the Middle East, has very troubling strands within it, and strands that I suspect go far beyond just the several dozen people who happen to have been rioting here.

Interestingly,

When Voltaire wrote the play in 1741, Roman Catholic clergymen denounced it as a thinly veiled anti-Christian tract. Their protests forced the cancellation of a staging in Paris after three performances — and hardened Voltaire's distaste for religion. Asked on his deathbed by a priest to renounce Satan, he quipped: "This is not the time to be making enemies."

Thanks to Peter Wizenberg for the pointer.

BATFE Director now needs Senate Confirmation:

If I were in Congress, I would have voted against the Patriot Act and its re-authorization. Although the Act does provide important anti-terrorist tools, I believe it is extremely overbroad, in part because so many of the special anti-terrorism powers are not limited anti-terrorism, but can be used to enforce any federal law. But one of the civil liberties improvements in the revised Patriot Act is contained in section 504. That section changes 6 U.S.C. 531(a)(2), so that the Director of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosive now requires Senate confirmation of his or her appointment. Even if BATFE did not have a troubled history on civil liberties issues (some of which is detailed in my book No More Wacos: What's Wrong with Federal Law Enforcement and How to Fix It), it makes sense for the head of any major federal law enforcement agency to be subject to the checks and balances of Senate confirmation.

Glaeser in NY Times Magazine:

If you missed the profile of Ed Glaeser in the New York Times Magazine, allow me recommend it to you. It is a great read in the "Freakonomics" mode, exploring Glaeser's heterodox views on cities and the impact of regulation on housing prices. An excerpt:

So, after sorting through a mountain of data, Glaeser decided that the housing crisis was man-made. The region's zoning regulations — which were enacted by locales in the first half of the 20th century to separate residential land from commercial and industrial land and which generally promoted the orderly growth of suburbs — had become so various and complex in the second half of the 20th century that they were limiting growth. Land-use rules of the 1920's were meant to assure homeowners that their neighbors wouldn't raise hogs in their backyards, throw up a shack on a sliver of land nearby or build a factory next door, but the zoning rules of the 1970's and 1980's were different in nature and effect. Regulations in Glaeser's new hometown of Weston, for instance, made extremely large lot sizes mandatory in some neighborhoods and placed high environmental hurdles (some reasonable, others not, in Glaeser's view) in front of developers. Other towns passed ordinances governing sidewalks, street widths, the shape of lots, septic lines and so on — all with the result, in Glaeser's analysis, of curtailing the supply of housing. The same phenomenon, he says, has inflated prices in metro areas all along the East and West Coasts.

Patriot Act Renewal:

The House passed the Patriot Act renewal bill today by a vote of 280 to 138. President Bush will sign the bill tomorrow. For the last few months, the debate over the Patriot Act has been over really small potatoes. To use a football analogy, the players were battling over inches instead of yards. But then everything associated with the Patriot Act tends to have a larger-than-life political significance. "Dog bites man" isn't a story, but "Patriot Act lets dog bite man" always gets splashed across the front page. In any event, I haven't seen the latest text, but I'll blog on the details after I do.

A Theory of the Academic Labor Market:

Steve Teles has an interesting discussion here.

He suggests that a nontrivial amount of academic quality is "endogenously" produced, e.g., that the "rich get richer" when it comes to scholarly success. This is almost certainly true and, it seems to me, it may even be even more pronounced in law schools. Most of the factors he identifies applies with equal force to legal academia, such as access to resources, research assistants, etc. Even the recognition and resources of institutions such as the Olin Foundation and the Federalist Society disproportionately flow to the top of the law school food chain. But the legal academy's unique institutional arrangement that it has neither peer review nor blind submission seems to strongly reinforce the factors that Steve notes in other fields.

In particular, it is my impression that law reviews operate very strongly on a signaling model of article quality. Because of their relative inexperience and lack of knowledge, law review editors seem to have difficulty accurately determining quality directly. To deal with this information problem, it appears that law review editors rely heavily on a signaling model of quality--i.e., if you are a "known" person or teach at a high-ranked school, this is thought to serve as a proxy for quality. And once your articles appear in a brand-name law review, you are thought to be important or accomplished.

This seems to be Teles's endogenous production of scholarly value within the academic market with a vengeance.

As an aside, I certainly don't think of peer review as a panacea for the law review system. The law review system has the advantage of allowing many flowers to blossom and to enable heterodox views to make it into print more readily than does the peer review system (although the peer review system has virtues of its own). So I think an argument could be made on either side of the issue regarding peer review.

But the absence of blind submission and review practices at most law reviews seems simply baffling to me. I can see no possible explanation for how the quality of law reviews and legal scholarship is improved by not having blind submission for law reviews. At least anecdotally, the "letterhead" effect seems quite powerful for law reviews (I am not aware of any rigorous empirical study that has been performed to date--if there is one, please let me know).

Stephenson on Choosing Between Agencies and Courts:

In the latest issue of the Harvard Law Review, Matthew Stephenson has a very interesting article on lawmaking by courts vs. agencies: Legislative Allocation of Delegated Power: Uncertainty, Risk, and the Choice Between Agencies and Courts (.pdf). Here is the abstract: When a legislature delegates the authority to interpret and implement a general statutory scheme, the legislature must choose the institution to which it will delegate this power. Perhaps the most basic decision a legislature makes in this regard is whether to delegate primary interpretive authority to an administrative agency or to the judiciary. Understanding the conditions under which a rational legislator would prefer delegation to agencies rather than courts, and vice versa, has important implications for both the positive study of legislative behavior and the normative evaluation of legal doctrine; the factors that influence this choice, however, are not well understood. This Article addresses this issue by formally modeling the decision calculus of a rational, risk-averse legislator who must choose between delegation to an agency and delegation to a court. The model emphasizes an institutional difference between agencies and courts that the extant literature has generally neglected: agency decisions tend to be ideologically consistent across issues but variable over time, while court decisions tend to be ideologically heterogeneous across issues but stable over time. For the legislator, then, delegation to agencies purchases intertemporal risk diversification and interissue consistency at the price of intertemporal inconsistency and a lack of risk diversification across issues, while delegation to courts involves the opposite tradeoff. From this basic insight, the model derives comparative predictions regarding the conditions under which rational legislators would prefer delegating to agencies or to courts. Adrian Vermeule comments here.

More on Roberts and Legal Scholarship:

Following up on yesterday's post about Chief Justice Roberts and legal authority, I did a quick check of the opinions John Roberts filed as a circuit court judge. I found a bunch of cases in which Roberts discussed or cited scholarly commentary. In every case, the commentary cited or discussed was a leading treatise. First, there was U.S. ex rel. Totten v. Bombardier Corp, 380 F.3d 488 (D.C. Cir. 2004), a case about the False Claims Act. In response to a reading of the Act offered by Judge Garland in dissent, Roberts wrote the following: The proposition that subsection (a)(2) harkens back to (a)(1), and that the latter requires presentment, is supported in scholarly commentary on the False Claims Act. A leading treatise on the False Claims Act states that "[t]he three requirements of Section [3729](a)(1)" — including the requirement "that a claim be presented to the United States" — are "still applicable" to Section 3729(a)(2). 1 JOHN T. BOESE, CIVIL FALSE CLAIMS AND QUI TAM ACTIONS § 2.01[B], at 2-21 (2d ed. Supp. 2004-1). The dissent's contrary conclusion — that subsection (a)(2) does not require any presentment that may be required under subsection (a)(1) — has tellingly little support. Second, from Koszola v. F.D.I.C., 393 F.3d 1294 (D.C. Cir. 2005), a First Amendment case: Nothing in the text of 5 U.S.C. § 1221, however, requires the district court to undertake the "clear and convincing" inquiry in terms of any particular legal "test," multi-factor or otherwise. "Clear and convincing evidence" is a common legal standard. See generally 9 WIGMORE ON EVIDENCE § 2498, at 424 (Chadbourn rev.1981) (standard of clear and convincing proof "commonly applied"); id. at 424-31 (cataloging instances in which standard is applied). Given the familiarity trial judges have with this standard, we do not think it grounds for reversal that the district court did not explicate its ruling according to a particular gloss. Third, from In re Tennant, 359 F.3d 523 (D.C. Cir. 2004): Mandamus jurisdiction over agency action lies, if anywhere, in the court that would have authority to review the agency's final decision. See FCC v. ITT World Communications, Inc., 466 U.S. 463, 468-69, 104 S.Ct. 1936, 1939, 80 L.Ed.2d 480 (1984); TRAC, 750 F.2d at 77-79; 16 CHARLES ALAN WRIGHT, ARTHUR R. MILLER & EDWARD H. COOPER, FEDERAL PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE § 3942, at 796 & n.70 (1996). It's hard to make very much of this, of course. But assuming Roberts maintains the same practices on the Supreme Court, this evidence from his years on the D.C. Circuit makes it seem a bit less likely that Roberts will differ from the other Justices in his willingness to note or engage with scholarly commentary. UPDATE: I rewrote the post after finding a few more examples. Related Posts (on one page): - More on Roberts and Legal Scholarship:

- Chief Justice Roberts and Legal Authority:

There Is No Islam, Only Islams:

In a sense this is restating the obvious, but sometimes the obvious is worth restating. Like all big religions, Islam not only has multiple well-defined subdenominations, but also varies greatly from time to time, place to place, and ultimately person to person. All of us know this about the religions we're most familiar with, such as Christianity and Judaism.

Is Christianity "a religion of peace"? Well, that depends on which Christians you're talking about, where they live, when they live, and what their personal temperaments are. Theological inquiries and quotations from the sacred texts will tell you very little about it. (The text and broad tradition of the religion likely influence practitioners' behavior in some degrees, but the result is very far from determinate, as the variety of Christian thought and, more importantly, Christian action, tells us.) There is no Christianity, only Christianities practiced by particular Christians and groups of Christians. Likewise for other religions. This doesn't make their warlike subgroups any less warlike, but it should make us skeptical of generalities about billion-member (or even million-member or likely multi-thousand-member) religions.

Max Boot, who knows a lot about international matters, points this out in much more detail. Here are the first few paragraphs:

Given the monstrous crimes perpetrated in the name of Allah, it is easy to despair about the future of the Muslim world. Nonstop news about bombings, beheadings and general bedlam will no doubt lead more and more Westerners to conclude that we are at war with an entire civilization.

In reality, Islam has no fixed identity. Like other religions, it is based on vague generalities whose application varies widely across time and place. A thousand years ago, the Muslim world was a center of learning while Europe was mired in the Dark Ages. Today, the positions are nearly reversed. But there are many different rooms in Dar al-Islam (literally, "house of submission"), and no two are alike.

He goes on to give examples from Malaysia and Qatar; I can't speak with confidence about those, except to say that I'm confident he knows much more about those matters than I do. But his broad point is entirely right.

We're #1!

Granted, in a very narrow field, and based on a very limited measure.

Texas Primary Results and the Right to Arms:

Yesterday's Texas primarary resulted in a major win for Second Amendment supporters at the Congressional level, with mixed results in state legislative races. U.S. Democratic Rep. Henry Cuellar faced a stiff challenge for Ciro Rodriguez, whom Cuellar had defeated in the previous election by only 50 votes. Cuellar has an A rating from the National Rifle Association, whereas Rodriguez received a C-.

The race in this heavily Hispanic and Democratic district was closely watched nationally as an indication of whether Hispanic politics were trended towards the center (Cuellar is slightly more conservative than Bill Clinton was when he was governor of Arkansas) or towards the hard left, with Rodriguez receiving substantial funds from DailyKos donors.

Last night, Cuellar won by nearly 5,000 votes, and received 58% of the votes cast. The results bode well for the national Democratic party, as the southern and western wings of the party continue to develop moderate candidates who can appeal to America's tens of millions of gun-owning voters.

The only other U.S. House primary in which the NRA was involved was in Tom Delay's district, where the A+ rated Delay easily defeated three challengers who did not answer the NRA's questionaire.

Cuellar's victory contrasted with the defeat of A rated incumbent Democratic State Senator Frank Madla by F rated Carlos Uresti in the 19th district. In other state legislative Democratic primaries, NRA-endorsed candidates had mixed success. The NRA-backed candidates won almost all of the Republican primaries.

Cabinet List:

Who is the next person in this list?

Bill Richardson, Anthony Principi, Gale Norton, John Ashcroft, Donald Evans, _________.

I have two separate possible answers in mind. One is/was a Cabinet Secretary; the other is/was not.

Law Schools in the News:

The New York Observer has an interesting article on competition between NYU and Columbia for hiring top law profs. Meanwhile, the controversy at Yale Law School over the Yale Law Journal's decision not to rescind an offer to publish an article co-authored by an individual who used a racial slur in an outline when he was a first-year Harvard Law student has hit the New York Times. Both stories via the WSJ Law Blog.

ETrade Bank Customer Service:

I'm having trouble with a new CD account I tried to open with ETrade Bank via the Internet. I called customer service, and, after getting a message that my wait time would be five minutes, I've now been on hold for forty-seven minutes. An individual I spoke to previously at ETrade financial said there is no record in their system of my name or social security number. I know I'm not imagining that I opened an account, because I wrote down my account name and password.

UPDATE: Fifty-seven minutes on hold, and another ten minutes for the customer service rep to figure out that they have no idea what happened to my account. I'm taking my banking business elsewhere.

Congratulations to Nate Oman:

Nate Oman, who has been associated with various legal blogs, will join the William & Mary Law School faculty in the Fall. Among other claims to fame, while still in college Nate spent the Summer of 1998 as my research assistant for You Can't Say That! Welcome to the world of legal academia, Nate!

Tuesday, March 7, 2006

Justice Breyer Offers Some Thoughts on the New Court:

The Associated Press has the very interesting story, via Howard.

Chief Justice Roberts and Legal Authority:

Over at LawCulture, David Barron has a very interesting post on the first opinions by Chief Justice Roberts: I was struck by the fact that the [Solomon Amendment] opinion cities solely to prior supreme court opinions, statutes, and regulations. No references to law review literature, treaties, casebooks, or anything else not written by one of the three branches themselves. That got me to thinking: perhaps it's not just foreign law that the new conservative judicial philosophy thinks is illegitimate; it's everything that's not an autoritative statement of a constitutionally recognized branch of govenrment. And that got me to looking. Thus far, the new chief has written two other opinions for the court. One finds the same citation pattern in each. Now that could just be a consequence of the kinds of opinions he's decided thus far. None, for example, has called for much delving into constitutional history. And, to be sure, it's only been three opinions. But still, I have my suspicions that this citation practice is intentional. if so, is it an attractive one or is it troubling? On the one hand, it has a kind of no nonsense quality about it — a just the facts ma'm style fully in accord with the new conservative judicial pose on display at the last two confirmation hearings. On the other hand, it might also suggest a vision of constitutional decision making that is awfully cramped and technical, in which the only guideposts are past cases, and statutory and regulatory texts stripped of their context, animating purposes or ideas. Lost in this approach is any sense of the broader legal culture that produces authoritative legal statements or the way in which such statements in turn shape the culture. It is statecraft by hornbook. It's too early to tell of course, whether there is anything to this "pattern." But it's worth watching — and challenging if it develops into an actual theory of constitutional decision making. As David suggests, we don't have enough evidence to see a trend. Relatively few Supreme Court opinions cite authority outside the relevant statutory text and prior Supreme Court opinions, so it's hard to know from two opinions if Roberts has a style different from the other Justices. However, if Roberts proves unusually disinclined to cite casebooks, articles, and treatises, he will be following the example of his former boss, William Rehnquist. Rehnquist saw a very sharp line between legal authority and mere commentary, and he didn't cite the latter as if it were the former. I wouldn't be surprised if Roberts has the same view. One interesting piece of evidence is a comment Roberts made in July 1997, during an appearance on the the Newshour that reviewed the October Term 1996. In discussing a recent case on the scope of Congressional power, Georgetown law prof Susan Bloch lamented that no one on the Rehnquist Court had discussed a theory that was popular in academic circles. Roberts added that this wasn't a bad thing: SUSAN BLOCH: For example, when we were talking about the Freedom--the Restoration of Freedom Act, the--there was the theory that Justice Brennan had that the court--that Congress could enlarge the scope of constitutional protections and couldn't constrict it? And that had a--when we teach constitutional law that's--that was a valid theory. On this court, no one, not even the dissenters, even talked about or embraced that theory, so that a number of theories that were in play when Justices Brennan and Marshall were on the court aren't even mentioned anymore.

MARGARET WARNER: How do you see it, John Roberts?

JOHN ROBERTS: Well, I think it's a moderate court but one that is very serious about the limits it sees in the Constitution, whether it's the limits on Congress, limitations on the federal government, or limitations on the court, itself. And if it's a court that doesn't seem so warm and embracing of theories that are popular on the law school campuses, I hope the other members of the panel will forgive me for not thinking that's a serious flaw. Related Posts (on one page): - More on Roberts and Legal Scholarship:

- Chief Justice Roberts and Legal Authority:

Adam Sandler, Legal Authority:

Even before the Order Denying Motion for Incomprehensibility (follow the links and look at p.2 n.1), came Krumnow v. Krumnow, 174 S.W.3d 820 (Tex. Ct. App. 2006) (Gray, C.J., Special Note):

As I was completing work on this Special Note, footnote 4 appeared in the majority opinion. That footnote states: "This is an accelerated appeal. Chief Justice Gray has had the opinion since April 26, 2005." Frankly, in setting my work priorities, I had overlooked that "this is an accelerated appeal." I was not reminded of that by the author of the opinion until the addition of the footnote approximately four hours before the opinion was to be released....

So my response to footnote 4 is, quoting Adam Sandler in The Wedding Singer, "Once again, things that could have been brought to my attention YESTERDAY!" The Wedding Singer (New Line Cinema 1998) (motion picture).

Actually, the rest of the Special Note, with its discussion of whether "two judges on a three judge court of appeals can issue an opinion and not wait for the third judge’s considered vote in an appeal" is more interesting, and actually pretty readable. But, hey, it doesn't quote Adam Sandler, so naturally we won't pay as much attention to it. Related Posts (on one page): - Adam Sandler, Legal Authority:

- Citing Madison:

Presidential Numbers:

It happened to Andrew Johnson 15 times, and Ford and Truman 12 times each. It never happened to LBJ, even though there were many opportunities, and it only happened to Cleveland twice, despite hundreds of opportunities. It couldn't have happened to 8 Presidents, starting with John Adams and running through George W. Bush. What is it?

Monday, March 6, 2006

Law School Responses to FAIR v. Rumsfeld:

From the George Mason Law School website:

March 6, 2006: By an 8-0 margin, the Supreme Court decided that Congress can give the military a statutory right to recruit prospective lawyers at law schools whose universities receive federal aid, grants or contracts. Rumsfeld v. FAIR, No. 04-1152.

The Court's decision closely follows the amicus brief filed by members of the George Mason law school community — the only members of the national community of law schools to brief the case in behalf of the armed services. Several dozen amicus briefs were filed on the losing side (including briefs in behalf of the professors at Yale University, Harvard University, Columbia University, New York University, Cornell University and the University of Pennsylvania), arguing that the Solomon Amendment's requirement of equal access for military recruiters was unconstitutional under the First Amendment.

The George Mason brief was signed by Dean Daniel Polsby and Professors Nelson Lund and Joseph Zengerle in behalf of four other George Mason professors, seven George Mason law students, and some eighty professors and students from other law schools. Lead counsel on the George Mason brief was Will Consovoy, ’01, along with Andrew McBride and Wiley, Rein & Fielding.

Dean Dan Polsby of George Mason Law School comments to Powerline:

This is really a stinging rebuke, not only to FAIR but to an entire industry that has become complacent and self-indulgent. Many law professors really do believe, with the late Justice Brennan, that their own strongly-held policy preferences are all encoded somehow in the Constitution. This is a timely reminder that it just isn’t so.

Meanwhile, from Georgetown's web site, solomonresponse.org:

The Supreme Court's opinion in Rumsfeld v. FAIR is a call to arms to law school administrations across the country to vocally demonstrate their oppostion to the military's "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy. Please visit the Protest & Amelioration section for more information.

Update:

Avery Katz of Columbia writes (in response to Dean Polsby's comment) to clarify that the Columbia law faculty brief (as distinguished from the Columbia University brief), as well as a similar brief by the Harvard law faculty (again, distinguished from the University), "was not based on any constitutional

issue, but instead made a statutory argument based on the text of the

Solomon amendment itself." The opinion, of course, considered and rejected that statutory argument as well.

National Review Article on George Mason Law School:

If you haven't seen the whole article, Paul Caron has an excerpt on his blog.

And National Review is currently featuring the first several paragraphs as a teaser here.

Citing Madison:

This time it's Billy, not James.

Let's Give the Muslim World a Message:

"We are aware of the consequences of exercising the right of free expression. We can and we are ready to self-regulate that right."

No, really, that's what the EU Justice and Security Commissioner is saying, according to Reuters:

The

European Union may try to draw up a media code of conduct to avoid a repeat of the furor caused by the publication across Europe of cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad, an EU commissioner said on Thursday.

In an interview with Britain's Daily Telegraph, EU Justice and Security Commissioner Franco Frattini said the charter would encourage the media to show "prudence" when covering religion.

"The press will give the Muslim world the message: We are aware of the consequences of exercising the right of free expression," he told the newspaper. "We can and we are ready to self-regulate that right." ...

Frattini, a former Italian foreign minister, said millions of Muslims in Europe felt "humiliated" by the cartoons.

His proposed voluntary code would urge the media to respect all religious sensibilities but would not offer privileged status to any one faith.

This isn't just about the EU's much more "reasonable" and "balanced" approach to free speech -- in words that I've heard from those who prefer the European approach to the American one, and would urge that it be adopted in America as well.

It's also about the EU's approach to appeasement, and to surrender. And don't tell me that the unnamed "consequences" are just public disapproval and strained international relations. When you say something like that against a backdrop of thugs burning embassies and killing people in reaction to your citizens' speech, appeasement and surrender are exactly what's going on, "voluntary" rules or not. Millions of Europeans should feel humiliated that one of their super-government's officials is even proposing this.

Thanks to Sister Toldjah for the pointer. Related Posts (on one page): - "EU-Ministers Considering Arab Demands":

- Let's Give the Muslim World a Message:

Quick reactions to the Solomon Amendment case:

Several quick reactions to today’s unanimous decision by Chief Justice Roberts in Rumsfeld v. FAIR, the Solomon Amendment case:

(1) The Court side-stepped the thorny and under-theorized question of government power to give money to an individual or institution on the condition that it relinquish the exercise of a constitutional right. This “unconstitutional conditions” doctrine holds that government may not so condition a benefit it confers, even though there is no independent “right” to the benefit itself. Thus, the federal government could decide not to have a food-stamp program. But it could not distribute food stamps (an elective government benefit) only to people who agree not to criticize the war in Iraq (which they have a constitutional right to do). On the other hand, the government can give money to people to send their children to public schools (an elective government benefit) but not to private schools (which they have a constitutional right to attend). The doctrine is a mess — and still is after today.

Much of the popular reaction to Rumsfeld v. FAIR prior to the decision suggested that this part of the case was easy: “If you don’t want to let military recruiters on your campus, don’t take the money. If you want the money, let the military recruit.” But this part of the case was never as easy as that reaction suggested.

While the Court acknowledged the unconstitutional-conditions issue, and the tensions in the doctrine (slip op. at 9), it didn’t address the issue because it decided there was no meritorious underlying First Amendment freedom being exercised by schools. The opinion has nothing valuable to say about this huge area of potential future constitutional litigation, an area that has special significance in an era of annual federal budgets approaching $3 trillion and a Congress eager to use this enormous economic leverage to get individuals, associations, and states to do its bidding.

(2) On the substantive question of whether the schools enjoyed a constitutional right to exclude military recruiters, the Court rejected three different “free speech” claims raised by FAIR. Schools are not “compelled” by the law to say anything very important, slip op. at 11-13, are not objectionably required to host the speech of the government within their own forum, slip op. at 13-15, and are not denied their right to engage in expressive conduct, slip op. at 16-18. In each case, the Court arguably narrowed its precedents, limiting the reach of free-speech rights.

Most interesting is its treatment of the “expressive conduct” doctrine. The Court has never had a satisfying theory of what conduct should get free-speech protection. Some conduct does get some level of protection (flag-burning, nude dancing) and some conduct doesn’t (perusing an adult bookstore). Different verbal formulations have been offered to explain the distinction but they’ve always been very indeterminate. Now the Court says that First Amendment protection extends only to conduct that is “inherently expressive.” Slip op. at 16. As best I can tell, this formulation of the test for what counts as protected expressive conduct is a new one.

It’s difficult to predict what conduct will count as “inherently expressive,” and thus get First Amendment protection, and what conduct will not be deemed “inherently expressive,” and thus get no First Amendment scrutiny. I'm not sure the distinction amounts to much more than the old obscenity standard, "We know it when we see it." The Court appears to mean that inherently expressive conduct is that conduct for which the expressive component is “overwhelmingly apparent,” and thus needs no further accompanying speech to signal that it is expressive. This, the Court thinks, helps us separate flag-burning (inherently expressive) from the exclusion of the military from law-school recruiting (not inherently expressive).

But is that right? We don’t know much about the message any conduct conveys, or whether it conveys any message at all, unless we know the context in which it occurs. Burning a flag could signal strong disagreement with the nation’s foreign policy (expressive), or could be accidental (not expressive), or could be an attempt to generate heat in the cold (not expressive), or could simply be disposing of a tattered flag in the manner prescribed by the government (not expressive?). Similarly, a law school's exclusion of the military could signal disagreement with some governmental or military policy, like Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (expressive), or could merely reflect that the law school ran out of space for interviews (not expressive). Context, including what the actor says about his conduct, matters. The uninformed observer, unaware of context, could not tell whether any particular act was expressive, so it should not matter that “listeners” or "observers" cannot appreciate why the law schools want to exclude military recruiters until they are told why. In fact, in the current environment of heightened sensitivity to law school recruitment policies, the reasonably informed observer has a good idea why a law school might want to exclude the military. Even if in principle we could draw a line between protected conduct and unprotected conduct that would leave schools’ recruitment policies outside the protected realm, the Court’s discussion of this question is unsatisfying.

The Court’s discussion also contains what may be a doctrinal error, albeit one that makes no difference in the outcome. The Court argues that in Texas v. Johnson, the 1989 flag-burning case, it “applied [United States v.] O’Brien and held that burning the flag was sufficiently expressive to warrant First Amendment protection.” Slip op. at 16. Johnson held the opposite: that the O’Brien test did not apply because the government’s interest in prohibiting flag-burning was related to the supression of free expression (and thus deserved stricter scrutiny than applied under O’Brien). “We are thus outside of O’Brien’s test altogether,” said the Johnson Court. I guess whether this is truly an error depends on what the Court means by "applying O'Brien," but at the very least the opinion is imprecise on this point (unusual for Roberts, a careful writer).

(3) The Court rejected the schools’ claim, relying on Boy Scouts v. Dale (upholding the associational right of the Boy Scouts to exclude a gay scoutmaster), that their freedom of association should allow them to exclude military recruiters. Slip op. at 18-20. There was much irony in the dispute over the meaning of Dale as it applied to this case. Some of the same people who criticized Dale as “anti-gay” six years ago relied heavily on it to make an aggressive claim about associational rights. Of course, the irony went both ways. Some conservatives who hailed Dale as a great victory for freedom six years ago argued for a very narrow interpretation of it.

There is much to say about the Court’s discussion of associational freedom. I’ll limit myself here to this: Gone is the Court’s insistence, explicit in the Dale opinion, that we must defer to the association’s own judgment about what types of government regulation would impair its message. While the Court agrees that associational freedom is not limited to decisions about membership, it now suggests that regulations of associations are objectionable only (?) if they “mak[e] group membership less attractive.” Slip op. at 20. This, too, is something we have not before seen in the Court’s decisions. Prior to this decision, I believe, the Court had worried primarily about the effect a regulation might have on the group’s ability to get across its message, however that impediment operated. Now the focus of associational freedom seems to have been narrowed to concerns about effects on membership that in turn may affect message.

One could support the Court’s result in this decision – that the Solomon Amendment is constitutional – while still being quite concerned about its potential narrowing effects on First Amendment freedoms. The upshot of the Court's view about free speech and associational rights is this: the government could require schools to admit military recruiters, not merely withdraw funds from schools that object to the recuiters' presence.

(4) As a practical matter, the ruling changes nothing in the steps many schools have taken to “ameliorate” the presence of military recruiters by, for example, hosting fora on the military’s policy on the day military recruiters are present, or posting notices of opposition to the presence of discrimination on campus, even outside the door where military recruiters are interviewing. In fact, the decision today appears to give a bright green light to these efforts that some schools may have avoided until now for fear they would lose funding. From the opinion:

The Solomon Amendment neither limits what law schools may say nor requires them to say anything. Law schools remain free under the statute to express whatever views they may have on the military's congressionally mandated employment policy, all the while maintaining eligibility for federal funds. See Tr. of Oral Arg. 25 (Solicitor General acknowledging that law schools could 'put signs on the bulletin board next to the door, they could engage in speech, they could help organize student protests.').

Slip op. at 10. There was some question before this decision whether schools that posted these notices, or even organized protests, might not be giving the military access to their facilities that was "equal" to the access given other employers. As a matter of statutory construction, that worry should be over. Thus, the Court suggests, ameliorate at will.

Is Israel in Violation of International Law?

Last week I blegged for information about this question, set forth my preliminary understanding of the issue, and enjoyed reading many excellent comments, pro and con, on the topic. I would now like to ask commenters for more analysis on two precise issues.

It seems to me that the strongest argument that Israel is in violation of international law is based on United Nations Security Council Resolution 446. Passed 12-0 (with the U.S. abstaining), the 1979 Resolution tells Israel to stop building settlements in the West Bank and Gaza. (The latter were abandoned in 2005, are so are now irrelevant to my question.) Arguments can be made that the Resolution is predicated on a defective reading of the Fourth Geneva Convention, but there is a good counter-argument that even if the Security Council's resolution is wrong, the resolution is still binding, as a matter of international law.

To be precise, Security Council resolutions adopted under Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter are binding, whereas resolutions adopted under Chapter VI are not. Resolution 446 does not state its source of authority; Wikipedia's discussion section contains some pro/con arguments on whether 446 is a Chapter VII resolution.

A second international law argument against Israel is that the West Bank settlements and the defensive barrier both violate the Fourth Geneva Convention. A key weakness in this argument, though, is that the Convention by its own terms applies only "between two or more of the High Contracting Parties." Israel is a High Contracting Party, but there appears to be no other High Contracting Party which can claim that Israel's West Bank policies violate the Party's Geneva Convention Rights. (Jordan is exercised sovereignty in the West Bank from its 1948 invasion of Israel until Jordan attacked Israel again in 1967, and was thrown out of the West Bank. Jordan later abandoned all claims of sovereignty to the West Bank.)

Israel has unilaterally said that it will follow parts of the the Fourth Geneva Convention regarding the West Bank, and Israel contends that it is following the Convention; but this argument seems less relevant, legally speaking, than whether Israel is legally obliged to obey the Fourth Geneva Convention.

The arguments that Israel has a legal obligation to do so seem extremely weak. For example, some people cite Article 1 of the Convention ("The High Contracting Parties undertake to respect and to ensure respect for the present Convention in all circumstances.") as if it makes a nullity of Article 2's specific deliniation of the only circumstances in which the Convention is legally applicable.

The article Laurence E. Rothenberg & Abraham Bell, Israel's Anti-Terror Fence: The World Court Case (2004), seems to make a quite persuasive case that the Fourth Geneva Convention is not legally applicable to the West Bank, even though I do not find every single argument in the article to be persuasive.

So I am asking commenters for legal analysis of whether Sec. Res. 446 is a binding Chapter VII resolution, and whether the Fourth Geneva Convention is legally applicable in the West Bank. Please focus on the legal issues, rather than pro/con arguments about Zionism etc. Most commenters for my previous post did a good job of keeping a legal focus, except for one repeat-offender ranter who had to be barred.

Are Senior Judges Unconstitutional?:

This is the provocative question addressed by co-authors Professor David Stras (a colleague of mine at Minnesota) and Ryan Scott (a former student of mine, now clerking for Judge Michael McConnell). It is available here. While I'm not entirely on board for their analysis, attention should be paid to these two rising young stars of the legal academy, who've been specializing lately in institutional reform proposals for the federal courts.

Here's a summary from the authors:

With burgeoning caseloads and persistent vacancies in many federal courts, senior judges play a vital role in the continued well-being of our federal judiciary. Despite the importance of their participation in the judicial process, however, senior judges raise a host of constitutional concerns that have escaped the notice of scholars and courts. Many of the problems originate with recent changes to the statute authorizing federal judges to elect senior status, including a 1989 law that permits senior judges to fulfill their statutory responsibilities by performing entirely nonjudicial work. Others arise from the ambiguity of the statutory scheme itself, which seems to suggest that senior status represents a separate constitutional office, requiring reappointment, even though senior judges nominally “retain” judicial office under federal law.

In the first scholarly article addressing the constitutionality of senior judges, the authors examine two general constitutional objections: (1) whether the requirement that senior judges be designated and assigned by another federal judge before performing any judicial work violates the tenure protection of Article III; and (2) whether allowing judges to elect senior status, without a second intervening appointment, violates the Appointments Clause. They also examine whether two specific types of senior judges - the “bureaucratic senior judge” who performs only administrative duties and the “itinerant senior judge” who sits exclusively on courts outside his home district or circuit - violate the Constitution.

The authors conclude that the current statute authorizing senior judges raises serious constitutional problems that should be addressed by Congress or the Judicial Conference of the United States. In that respect, they formulate a number of straightforward suggestions to repair senior status without having to sacrifice any of the considerable benefits that senior judges have conferred on the federal judiciary over the years.

Lund and Lerner on Humility and the Supreme Court:

My GMU colleagues Nelson Lund and Craig Lerner have a provocative piece over at National Review online suggesting how we can move the Supreme Court away from the current nine cults of personality that prevail to a more truly conservative Court:

Take away their law clerks....

We propose to leave the justices free to decide how many cases to hear, and which ones. But Congress should require them to hear at least one diversity case for every federal question case they accept for review....

Bring back circuit riding....

Eliminate signed opinions....

I'd give the Justices one clerk to handle mundanities like correspondence, administrative tasks, and proofreading and citechecking. I think this would take care of the problem of multiple, idiosyncratic opinions without resorting to doing away with signed opinions. Relying on mature lawyers (the Justices) rather than green clerks to decide which cases to grant cert. would likely also move the Court in the direction of accepting fewer nude dancing and more commercial cases. But I think riding circuit would be a lot more productive use of the Justices' summers than whatever they do currently.

UPDATE: I cut this back because between my post and Todd's below, we reprinted too much of the article.

Lund and Lerner on The Supreme Court:

My colleagues Nelson Lund and Crag Lerner have a provocative column "Precedent Bound" with some ideas on how to restore some sense of humility to the members of the Supreme Court. Here's a snippet of the central problem in their mind:

Both liberals and conservative justices write popular books about legal topics, and even about their own lives. Judicial opinions are increasingly filled with such grandiosity as this: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life” (Planned Parenthood v. Casey). The justices freely let us know when they like or dislike a result that the law dictates, how they would have voted if they were legislators, and where they think Congress could improve the law. And sometimes we’re even reminded that if Americans aspire to be a law-abiding people, “their belief in themselves as such a people is not readily separable from their understanding of the Court invested with the authority to decide their constitutional cases and speak before all others for their constitutional ideals” (ibid). Not much humility there.

Perhaps most important, constitutional law is becoming an aggregation of nine idiosyncratic theories and nine bodies of personal precedent. To a degree that would have shocked the Founders, today’s justices care more about fidelity to their own individual past pronouncements than about stability and predictability in the decisions of the Court itself. Even if Roberts and Alito sincerely admire the self-effacing virtues of old-time judges, reversing history will require assistance from outside the Court.

They offer several concrete proposals for restoring humility to the Court, several of which may be somewhat tongue-in-cheek.

Speculating About the Unanimous Opinions:

Over at Bench Memos, Ed Whelan comments: The emerging story of this Supreme Court term would appear to be how many supposedly controversial cases have yielded unanimous opinions. A honeymoon for Chief Justice Roberts? A testament to his leadership? Or something else? Meanwhile, Marty Lederman comments on today's decision here.

Oscar Records:

Besides the upset for Best Picture at last night's Oscars, the awards were also notable in that the Best Picture winner (Crash) only won in three categories (Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, Best Editing). What was the last Best Picture winner not to win more than three Oscars?

Besides Crash, no other movie this year won more than three Oscars (though three movies -- Brokeback Mountain, Memoirs of a Geisha, and King Kong -- tied with Crash). What was the last year in which no movie won more than three Oscars?

Rumsfeld v. FAIR:

The Supreme Court has decided Rumsfeld v. FAIR, the Solomon Amendment case, and has reversed the Third Circuit and upheld the statute in a 21-page opinion by Chief Justice Roberts. The vote was 8-0, with Justice Alito not participating. From the conclusion of the opinion: In this case, FAIR has attempted to stretch a number of First Amendment doctrines well beyond the sort of activities these doctrines protect. The law schools object to having to treat military recruiters like other recruiters, but that regulation of conduct does not violate the First Amendment. To the extent that the Solomon Amendment incidentally affects expression, the law schools' effort to cast themselves as just like the schoolchildren in Barnette, the parade organizers in Hurley, and the Boy Scouts in Dale plainly overstates the expressive nature of their activity and the impact of the Solomon Amendment on it, while exaggerating the reach of our First Amendment precedents. Thanks to Howard for the link. UPDATE: This outcome wasn't hard to predict, but I thought I would note that my crystal ball was pretty much right on this one. From May 2005: "Gazing into my crystal ball, I predict that the Court will reverse. I don't think it will be close, either: maybe 9-0, with a concurrence or two." No concurrences were filed, but then the new Chief Justice wasn't on the bench when I made the prediction.

The Red Menace, Revisited:

That's the title of my forthcoming Northwestern University Law Review review essay of Martin Redish's The Logic of Persecution: Free Expression and the McCarthy Era. You can find the whole text at SSRN.

Here's the abstract:

This is a review essay of Martin Redish, The Logic of Persecution. This book wades into the debate over the legacy of the anti-Communism of the late 1940s and 1950s. Its unique contribution is to approach this controversy from the perspective of First Amendment theory, taking into account recent evidence that the Communist Party, USA (CPUSA) was the American arm of the Stalinist Soviet enemy, and was heavily implicated in espionage against the United States.

Part I of this Review discusses the Smith Act prosecutions, in which CPUSA leaders were prosecuted for promoting violent revolution against the government. This Reviewer agrees with Redish's conclusion that the prosecutions were unconstitutional. However, in judging the Smith Act prosecutions, historians may consider not only constitutional issues, but the moral status of the defendants; whether freedom of expression suffered any lasting harm; and whether the goal of destroying the CPUSA's usefulness to the USSR for espionage was, in context, a particularly important one.

Part II of this Review evaluates the infamous "blacklist" by Hollywood movie studios of members of the CPUSA. Redish concludes, and this Reviewer agrees, it was entirely appropriate - under the First Amendment, and also morally - for businesses and individuals to boycott members of the Stalinist CPUSA.

Finally, Part III of this Review discusses whether state and local governments acted within their constitutional authority in refusing to hire CPUSA members as teachers. Redish concludes that school authorities did not violate the First Amendment when they excluded devoted Communists from teaching classes in subject areas that required teachers to pass along a liberal democratic perspective to their students. Part III reviews some objections to Redish's conclusion, and suggests that monitoring compliance with the assigned curriculum would have been an alternative means of accomplishing the government's agenda.

In writing this review, I found the historical issues at least as interesting as the First Amendment issues. I've blogged a bit about this before, so suffice for now to say that the history of the "Red Scare" was rather different than I had believed, much less than what one might pick up from the popular media. Here's a small taste:

But the fact remains that the most of those blacklisted[in Hollywood] were at least as morally complicit in Stalinist crimes as a typical American Nazi of the 1930s and 40s was complicit in Nazi crimes. Communist screenwriters, in particular, "defended the Stalinist regime, accepted the Comintern's policies and about-faces and criticized enemies and allies alike with infuriating self-righteousness .... screen artist reds became apologists for crimes of monstrous dimensions. ... film Reds in particular never displayed any independence of mind or organization vis-a-vis the Comintern and the Soviet Union." Nor was the screenwriters' Communist activism irrelevant to their jobs, as they actively sought to maximize Communist and pro-Soviet sentiment in films, and minimize the opposite.

And please, to avoid strawman arguments, look at the review before commenting.

Sunday, March 5, 2006

If It's Sunday, It's a VC Open Thread:

What's on your mind? Comment away.

|

|