|

Friday, February 29, 2008

Agreements to Raise a Child in a Religion:

My coblogger David Bernstein wrote, in a comment to my preference-for-agnostic-parent hypothetical,

It strikes me that if there is uncontested evidence that the parents agreed to raise their children in a certain, nonabusive way when they got married, the parent that follows through on the deal SHOULD be favored, whether the agreement was atheism, or religion, or whatever.

Here's my thinking on this. I'm generally a believer in enforcing contracts, even when a party changes his mind about them. The power to enter into binding contracts is an important power.

1. Nonetheless, precisely because contracts are binding, the legal system has to distinguish contracts that the parties intend to be legally binding from plans or tentative agreements that express a party's current views but that don't purport to legally bind the party in the future. "I will always love you" said to a lover is a classic example: If you want to make it legally binding (even to the limited extent that marriages are legally binding these days), you have to go through some pretty significant formalities. Without those formalities the agreement is understood as expressing a desire, a hope, or a plan, not a legally binding commitment.

Likewise with "[Christianity / objectivism / music lessons] are an important factor to me, and I feel strongly about raising our daughter this way." One can be entirely sincere about this, and in fact plan to stick by this, without intending to make a binding commitment. In fact, many people -- knowing how time and experience leads us to change our views on many subjects -- would rightly balk at making such binding commitments (just as they often, though not always, balk at turning "I will always love [my boyfriend/girlfriend]" into a binding commitment).

So if there is evidence that the parents agreed to make a binding commitment to raise their children in a certain, nonabusive way, there would be at least a serious argument in favor of enforcing the contract (though one would need to know to what extent the best-interests test can be displaced under state law by such contracts). But it seems to me a mistake to infer such a binding, long-term commitment simply from an agreement in principle, as to matters on which people's attitudes often change with time.

2. It's also important that contracts, especially contracts about religion, are clear enough that courts can sensibly enforce them. An agreement's vagueness is often a sign that the parties didn't intend it to be binding. But given the Establishment Clause constraints on theological judgments by courts (even when the courts are interpreting contracts or wills that expressly call for such judgments), it's especially important that the contract be clearly applicable using the court's strictly secular interpretive approach.

My sense is that many casual agreements about religion or the importance of religion are not sufficiently clear. "I agree that we should raise our child Jewish," for instance, leaves a great deal uncertain. Obviously, the particular strain of Judaism isn't mentioned. Neither is the intensity of the raising -- does it mean that Judaism (whether Orthodox or Reform) would be a pervasive part of the child's life, just that the child would be exposed to some of the most important aspects of Judaism (i.e., become a High Holidays Jew, though perhaps with a bit more intensity around Bar Mitzvah time), or something in between? Neither is the specific degree to which the raising would involve organized religion, rather than just individualized study. Neither is the degree to which the child would be exposed to rival views (which may become important if the parents divorce and one converts to a different religion, and exposes the child to that religion without otherwise interfering with the child's religious rituals).

Now each of us can have a sense of which side is complying more closely with even a vague agreement. There might even be a good deal of consensus on the subject. But in such cases, I don't think this sort of consensus is an adequate basis for courts to decide, because it involves too much subjective judgment about what are the "true" rules of certain religions, and which of those are "central" -- something courts are barred by the Establishment Clause from doing.

For instance, is an agreement to raise the kids Jewish violated by a parent who tries to raise them as Jews for Jesus? I know that many Jews believe it would be, and in some sense they might be right. But I don't think that a secular American court is allowed to decide whether or not Jews for Jesus is "really Jewish," whether Reconstructionist Judaism is "really Jewish," whether Reform Judaism is "really Jewish," or for that matter whether Mormonism is "really Christian."

So it seems to me that even if the parties are intending to create a legally binding agreement (which they often won't be), many kinds of religious agreements would still be unenforceable by secular courts. Perhaps some might be, for instance an express agreement that the child would be sent at least twice a month to churches of a particular organization, or an agreement that the religious terms of the agreement are to be subjected to binding arbitration through some private religious body (such as a Jewish Beth Din). But they would have to be drafted in such a way as to avoid the need for religious decisionmaking by a secular court.

3. Finally, I should note that if one thinks the court making a custody decision should mostly focus on the best interests of the child (subject to whatever constitutional constraints there may be), then it's not clear to me to what extent the court can consider the parties' contract, which need not be aimed at the child's secular best interests. (Sometimes departing from such a contract would be against the child's best interests, but not always and not necessarily even most of the time.) But one could certainly argue that state family law should sometimes subordinate the best interests standard to reasonable agreements between the parties -- setting aside the other objections I raised above -- especially when enforcing such agreements can often yield more certainty, quicker and cheaper resolution, and decreased acrimony.

Michigan Court Prefers Agnostic Parent Over a Parent Who Has Been Finding Religion:

Here's an excerpt from a recent Michigan court decision:

The Plaintiff [father] testified that agnosticism and scientific rationalism were important factors to both parties when they were first married and both felt strongly about not raising their daughter in organized religion. The Plaintiff remains consistent in not attending any religious services with the daughter. The Plaintiff's testimony and actions appear to be sincere in raising the daughter outside any organized religion.

The Defendant [mother] testified that she was more firm in avoiding religious organizations during the summer, but during the winter months she found herself drawn to church, both because of the friendly environment and community feeling it provides, and because her earlier opposition to religion has been softening. The Defendant testified that she has allowed the daughter to make the decision as to whether or not she attends church. However, the court agrees with the Plaintiff that this is not a decision which should be left up to a young child who was 3½ at the time of the decision. The Plaintiff testified that the Defendant has admitted to him that she takes daughter to church occasionally and does not feel that it will make a difference.

The Plaintiff appears to be more consistent in avoiding organized religion with the daughter on a regular basis now that the parties have separated. The court must remain neutral with respect to each of the parties' religious beliefs, however, both parties agreed that agnosticism and scientific rationalism was an important factor when they were first married and when they started their family. Since the parties have separated, the Plaintiff is the parent who has actively participated in the daughter's agnostic, rationalistic upbringing while the Defendant has allowed the daughter to make the decision on whether she attends church....

As to raising the daughter in her absence of religion, the Court concludes that this factor favors the Plaintiff.

Of course, this isn't a real decision -- it's a recasting of the decision I blogged about yesterday, in which the court preferred the more religiously observant parent over a parent who has moved towards having less interest in exposing her daughter to organized religion. But I think it's a useful way of looking at the problem.

It seems to me that this hypothetical decision would be a First Amendment violation. Remember that the judge wouldn't be finding any specific secular harm to the child from the change; there'd be no evidence that the child is finding the change to be disruptive (in fact, the child seems to prefer it), and no evidence that the religious services somehow involve some physical danger to the child. Nor would the judge be finding any binding contract to raise the child irreligious; there's no evidence of a willingness to be so bound, and no legal hook for the court to consider the contract between the parties in making a decision that's supposed to be about the best interest of the child.

The judge would simply be saying that a parent who had moved towards greater religiosity since when the child was born should be disfavored. And secular courts are not supposed to make such judgments.

But if I'm right, then how could the actual child custody decision (quite commonplace in Michigan courts, and some other courts, or so my research suggests) be constitutional? If a court can't hold against a parent the fact that she has moved away from agnosticism and towards religiosity, how can it hold against a parent the fact that she has moved away from organized religion and towards less church attendance?

Now There's a Bit of Hostile E-Mail for You:

Just got it in my mailbox:

hellow nonsense person u know we r all the creature of God and we go to die one day then y u insult any other religion for the sake of just some people or temporatry popularity..... o stupid its a big sin for everyperson..... so u should try to appologise ur sin bu God and never try again this kind of mistake whenever ............

just go to hell disguesting guy......

Uh, OK.

"Quaker Teacher Fired for Changing Loyalty Oath":

The San Francisco Chronicle reports:

Marianne Kearney-Brown, a Quaker and graduate student who began teaching remedial math to [California State University East Bay] undergrads Jan. 7, lost her $700-a-month part-time job after refusing to sign an 87-word Oath of Allegiance to the Constitution that the state requires of elected officials and public employees....

[W]hen asked to "swear (or affirm)" that she would "support and defend" the U.S. and state Constitutions "against all enemies, foreign and domestic," Kearney-Brown inserted revisions: She wrote "nonviolently" in front of the word "support," crossed out "swear," and circled "affirm." All were to conform with her Quaker beliefs, she said....

Modifying the oath "is very clearly not permissible," the university's attorney, Eunice Chan, said, citing various laws. "It's an unfortunate situation. If she'd just signed the oath, the campus would have been more than willing to continue her employment." ...

"Based on the advice of counsel, we cannot permit attachments or addenda that are incompatible and inconsistent with the oath," the campus' human resources manager, JoAnne Hill, wrote ....

Hill said Kearney-Brown could sign the oath and add a separate note to her personal file that expressed her views. Kearney-Brown declined. "To me it just wasn't the same. I take the oath seriously, and if I'm going to sign it, I'm going to do it nonviolently." ...

Now I appreciate Cal State's desire to follow the law; the California Constitution does prescribe the text of the oath, and says "all public ... employees, ... except such inferior officers and employees as may be by law exempted, shall, before they

enter upon the duties of their respective offices, take and subscribe the following oath or affirmation." But surely there are times to interpret laws as requiring substantial compliance rather than strict literalism. Even the precedent that Ms. Hill cites as supposedly requiring the exact text of the oath (see the article for more on that) seems to take this view: It rejected the applicant's modified oath only after stressing that the modifications were not "surplusage" or "innocuous or merely expository," but rather "ma[d]e equivocal the essential oath preceding [the applicant's personal statement]." Likewise, the venerable principle that laws should be interpreted in a way that minimizes possible constitutional problems (here chiefly First Amendment problems related to compelled speech) counsels in favor of reading the law to provide some flexibility. In light of this, letting Ms. Kearney-Brown sign the entire oath, simply with the addition of a term, seems sufficiently consistent with the state mandate.

True, the Supreme Court has held that it doesn't violate the First Amendment to require certain narrow loyalty oaths, including support-and-defend oaths, for government employees. But the Court's justification was precisely that these oaths "do[] not require specific action in some hypothetical or actual situation"; they embody "simply a commitment to abide by our constitutional system ... [and] a commitment not to use illegal and constitutionally unprotected force to change the constitutional system."

Adding "nonviolently" to the oath (or affirmation) thus doesn't change its legal meaning: As the Supreme Court pointed out, the original oath has never been understood to require violent action. Draft laws and other laws may sometimes require such action, but they generally don't require it of women, and in any event it is those laws -- not the oaths required of a wide range of nonmilitary government employees -- that require the action.

So it looks like the state is losing a valuable employee, and has to spend time, money, and effort hiring a new employee. And people who (for religious reasons or other reasons) oppose violence and are especially scrupulous about not promising what they can't deliver lose the opportunity to work in state jobs. As I said, I agree the government should follow the law. But surely the law has enough flexibility in it to avoid this sort of pointless result.

Thanks to Joel Sogol for the pointer.

McCain's birth, Russian language version:

In this Russian-language radio broadcast for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, I add my own thoughts to the controversy. Synopsis: the issue hasn't been clearly settled by the courts, but most legal scholarship supports McCain's eligibility. His eligibility is strongly supported by the fact that he was born on American soil, since he was born in the Canal Zone. The clause was intended to prevent dual loyalty, which is not an issue in McCain's case, since he was an American citizen at the moment of his birth, and he was never a citizen of Panama or any other nation. Thus, this is an easier case than someone who was born on foreign soil, and who received foreign citizenship as a result of that birth. (E.g., a child born to American private-sector workers who were living in Ireland at the time of the birth; although I argue that even in this case, most legal scholarship would favor that child being considered "a natural-born citizen.")

Interesting Presidential Poll:

It seems that everyone I know, Republican and Democrat, liberal and conservative, thinks that Barack Obama is wildly popular and a virtual shoe-in to become president if he receives the Democratic nomination. At least one poll suggests otherwise. According to Rasmussen,

Thirty-four percent (34%) of all voters say they will definitely vote for John McCain if he is on the ballot this November. Thirty-three percent (33%) will definitely vote against him while 29% say their support hinges on who his opponent is.

Barack Obama has the same number who will definitely vote for him--34%. But, more people are committed to voting against him than McCain. Forty-three percent (43%) say they will definitely reject him at the ballot box.

I understand that this is just one poll, and we've all learned to be skeptical of polls. But this one is so contrary to the conventional wisdom that when I've mentioned it to people, they express sheer disbelief. So here it is.

Religious Upbringing and Changes in Attitudes:

I just got the trial court opinion in Kik v. Kik, the latest Michigan appellate case that counted a parent's greater religious observance as a factor in favor of the parent's custody claim. Here's what the trial judge wrote about this:

As far as religion, the testimony indicates that the child was baptized at Saint Paul's in Big Rapids which is where the parties were married. The Plaintiff testified that religion was an important factor to both parties when they were first married and both felt strongly about raising [their daughter] in the church. The Plaintiff also admitted that after they were married it was a struggle for them to attend church, however, since the separation the Plaintiff has been more consistent with attending church and taking [the daughter] with him on a regular basis. The Plaintiff attends church every week at Saint Mary's of the Woods Catholic Church in Kalkaska and takes [the daughter] with him to church on a regular basis. The Plaintiff's testimony and actions appear to be sincere in raising [the daughter] in the church.

The Defendant testifies that she also attends church at Saint Paul's in Big Rapids which is where [the daughter] was baptized. The Defendant testified that she was more regular in attending church during the summer, however, has not been regular in attendance during the winter months. The Defendant testified that she has allowed [the daughter] to make the decision as to whether or not she attends church. However, the court agrees with the Plaintiff that this is not a decision which should be left up to a young child [who was 3½ at the time of the decision]. The Plaintiff testified that the Defendant has admitted to him that she does not take [daughter] to church on a regular basis and does not feel that it will make a difference.

Although the parties struggled to attend church while they were married, the Plaintiff appears to be more consistent in attending church with [the daughter] on a regular basis now that the parties have separated. The court must remain neutral with respect to each of the parties['] religious beliefs, however, both parties agreed that religion was an important factor when they were first married and when they started their family. Since the parties have separated, the Plaintiff is the parent who has actively participated in [the daughter]'s religious upbringing while the Defendant has allowed [the daughter] to make the decision on whether she attends church....

As to raising [the daughter] in her religion, the Court concludes that this factor favors the Plaintiff.

Now I realize that the judge said she was remaining neutral with respect to the parties' religious beliefs — but I think that this decision was not neutral, and was based on favoritism (which, I think, violates the Establishment Clause) for the more religious parent.

To begin with, note that this is not a case where continuity of religious upbringing is valued simply because it prevents disruption for the child. I can imagine why a child who is closely involved with her church would be hurt by being separated from church activities and from her church friends. But here there's no evidence to controvert the mother's claim that the daughter prefers not to go to church often, and no evidence to suggest that this reduced churchgoing is causing disruption in the daughter's life.

Also, this is not a case where the court is enforcing a contract providing for the religious upbringing of the child. True, the parents apparently "agreed that religion was an important factor ... when they started their family." But there's no evidence that the parents entered into what they reasonably saw as a binding contract. Not every understanding or plan is seen by the parties as a binding contract, and that's good; we can value lots of things and plan lots of things without surrendering our rights to change our minds.

And this right to change one's mind is especially important for religion, a subject on which people do often change their minds. One's religiosity, and one's perception of the importance of religiosity to one's children, may well change. The divorce itself may shake one's faith in God (especially if one is Catholic). Seeing one's child grow may deepen one's religious beliefs or weaken them. Seeing how one's child behaves may change one's view about whether the child is getting something valuable out of organized religion. The pressures of everyday life may change one's perception of how much of one's scarce parenting time and energy one should devote to organized religion. And of course sometimes people may have religious epiphanies. One should not lightly infer a promise to maintain one's religious practices (or the nature of the upbringing one plans to give one's child) from a past general agreement that religion is an important factor.

What's more, note that the judge wasn't purporting here to enforce a contract between the parties. She was just deciding what was in the child's best interests. Even if explicit contracts to raise a child in a particular religious manner should be upheld (and I'm inclined to say they can be, if this can be done with a minimum of entanglement with theological questions, but that's a matter for another day), there's no reason to think any such enforcement was taking place here.

So what we have here is a judgment that, once two parents generally agree to raise a child religiously, it's in the child's best interests to continue that upbringing — even when one parent changes her views about religion, or about the importance of organized religious observance, and even when there's no particularized evidence that this child is seeing the change as disruptive. On other matters, I take it, a court wouldn't take the same view: One wouldn't hold it against a parent that she acceded to the 3½-year-old's request to stop taking ballet lessons. But as to religious practice, the one area where governmental coercion poses the greatest constitutional problems, the judge was holding a parent's change in attitude and behavior against that parent.

Once a child is being exposed to organized religion, the reasoning seems to go, it's in the child's best interests to continue this exposure, even when the child isn't interested, when stopping the exposure isn't causing disruption, when one parent thinks the exposure is unnecessary, and when the other parent would be free to expose the child himself during his time with the child. I can't see how that is consistent with the Establishment Clause principles that the government generally may not prefer religious behavior over secular behavior, and that the government may not coerce people into engaging in religious practice.

Perhaps the decision wasn't this particular trial judge's fault, given what seems to be the Michigan state legal principles that push in this direction. But it seems to me unconstitutional nonetheless.

UPDATE: Several commenters suggest that the mother was properly faulted for not living up to her supposed values, because she has supposedly been saying one thing (church is very important) and doing another (not taking the child to church regularly). I'm not sure that this would be a sensible position for the court to take, but before we can evaluate that, wouldn't we need to see some specific evidence that the mother is being inconsistent?

I see no such evidence in the trial court opinion. There's evidence that mother once thought church attendance was important. But now it seems that she "does not feel that it will make a difference" to the child, and in fact doesn't attend church regularly. Sounds like someone who has changed her views about organized religion, and no longer finds church attendance to be as important as she once did. That's hardly evidence of inconsistency, hypocrisy, or failure to live up to claimed values.

The New 7½:

I'm turning it today. Yow. I guess I can't be an enfant terrible any more, so I'm working on becoming an eminence grise instead.

Why Did President Bush Advocate War with Iraq?:

As 'a cover-up for a failing economy.'"

Guess who said that. Answer below.

State Senator Obama, as quoted in the Chicago Defender, Sept. 26, 2002, at 1. Apparently, before the "politics of hope" came the "politics of cynicism."

The meaning of "natural born."

I read with some amusement the struggles that some non-lawyers [and some lawyers as well] have been having understanding the language of Art II, Sec. 1 of the U.S. Constitution: "No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President . . . ." If the drafters of the Constitution had wanted to require that presidents be born in the United States, they could have done so. Instead, they invoked the then-standard idea of natural citizenship as reflecting natural allegiance to the king or the state.

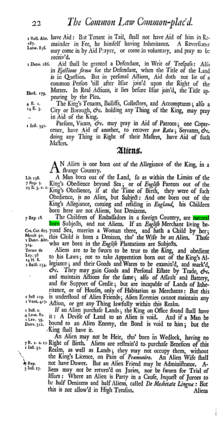

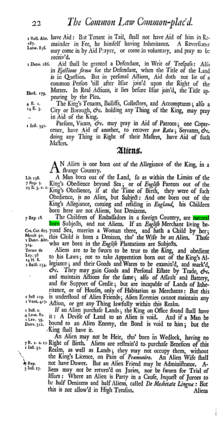

Standard 18th century dictionaries and commentaries couldn’t have been clearer on this point. For example, Giles Jacob in The New Law-Dictionary (1743) and The Common Law Common-plac’d (1733) made clear who was an alien and who was a "natural born subject”:

The Children of Ambassadors in a foreign Country, are natural born Subjects, and not Aliens. Id. at 22 (Eighteenth Century Collections Online)

(click to enlarge)

Blackstone has a lengthy treatment:

William Blackstone, Commentaries 1:354, 357--58, 361--62 (1765)

The first and most obvious division of the people is into aliens and natural-born subjects. Natural-born subjects are such as are born within the dominions of the crown of England, that is, within the ligeance, or as it is generally called, the allegiance of the king; and aliens, such as are born out of it. Allegiance is the tie, or ligamen, which binds the subject to the king, in return for that protection which the king affords the subject. The thing itself, or substantial part of it, is founded in reason and the nature of government; the name and the form are derived to us from our Gothic ancestors.

. . . . .

Allegiance, both express and implied, is however distinguished by the law into two sorts or species, the one natural, the other local; the former being also perpetual, the latter temporary. Natural allegiance is such as is due from all men born within the king's dominions immediately upon their birth. For, immediately upon their birth, they are under the king's protection; at a time too, when (during their infancy) they are incapable of protecting themselves.

Natural allegiance is therefore a debt of gratitude; which cannot be forfeited, cancelled, or altered, by any change of time, place, or circumstance, nor by any thing but the united concurrence of the legislature. An Englishman who removes to France, or to China, owes the same allegiance to the king of England there as at home, and twenty years hence as well as now. For it is a principle of universal law, that the natural-born subject of one prince cannot by any act of his own, no, not by swearing allegiance to another, put off or discharge his natural allegiance to the former: for this natural allegiance was intrinsic, and primitive, and antecedent to the other; and cannot be devested without the concurrent act of that prince to whom it was first due. Indeed the natural-born subject of one prince, to whom he owes allegiance, may be entangled by subjecting himself absolutely to another; but it is his own act that brings him into these straits and difficulties, of owing service to two masters; and it is unreasonable that, by such voluntary act of his own, he should be able at pleasure to unloose those bands, by which he is connected to his natural prince.

Local allegiance is such as is due from an alien, or stranger born, for so long time as he continues within the king's dominion and protection: and it ceases, the instant such stranger transfers himself from this kingdom to another. Natural allegiance is therefore perpetual, and local temporary only: and that for this reason, evidently founded upon the nature of government; that allegiance is a debt due from the subject, upon an implied contract with the prince, that so long as the one affords protection, so long the other will demean himself faithfully. As therefore the prince is always under a constant tie to protect his natural-born subjects, at all times and in all countries, for this reason their allegiance due to him is equally universal and permanent. But, on the other hand, as the prince affords his protection to an alien, only during his residence in this realm, the allegiance of an alien is confined (in point of time) to the duration of such his residence, and (in point of locality) to the dominions of the British empire.

. . . . .

When I say, that an alien is one who is born out of the king's dominions, or allegiance, this also must be understood with some restrictions. The common law indeed stood absolutely so; with only a very few exceptions: so that a particular act of parliament became necessary after the restoration, for the naturalization of children of his majesty's English subjects, born in foreign countries during the late troubles. And this maxim of the law proceeded upon a general principle, that every man owes natural allegiance where he is born, and cannot owe two such allegiances, or serve two masters, at once. Yet the children of the king's embassadors born abroad were always held to be natural subjects: for as the father, though in a foreign country, owes not even a local allegiance to the prince to whom he is sent; so, with regard to the son also, he was held (by a kind of postliminium) to be born under the king of England's allegiance, represented by his father, the embassador.

To encourage also foreign commerce, it was enacted by statute 25 Edw. III. st. 2. that all children born abroad, provided both their parents were at the time of the birth in allegiance to the king, and the mother had passed the seas by her husband's consent, might inherit as if born in England: and accordingly it hath been so adjudged in behalf of merchants. But by several more modern statutes these restrictions are still farther taken off: so that all children, born out of the king's ligeance, whose fathers were natural-born subjects, are now natural-born subjects themselves, to all intents and purposes, without any exception; unless their said fathers were attainted, or banished beyond sea, for high treason; or were then in the service of a prince at enmity with Great Britain.

According to even the most technical meaning of "natural born" citizen in the 1780s, John McCain is a natural born citizen of the United States, but George Washington and Thomas Jefferson may not have been (since they were born before 1776), though they would have been generally treated as such at the time.

Thursday, February 28, 2008

Bies v. Bagley:

Decision of the Day has a post on the Sixth Circuit's latest capital habeas case, Bies v. Bagley. Bob's take: While the decision granting habeas relief is "remarkable" and "creative," in the end "reversal is inevitable."

"Natural-Born Citizen":

I'm not an expert on this, but I'm pretty sure that Sen. McCain is a "natural-born citizen" and thus eligible to be President: He was a citizen from birth, having been born to citizen parents (his father was stationed in the Canal Zone). My sense is that "natural-born citizen" is most plausibly interpreted as being a citizen from birth.

Nonetheless, I'm pretty sure that the Senator erred when he said,

Barry Goldwater was born in Arizona when it was a territory, Arizona was a territory, and it went all the way to the Supreme Court.

Unless I'm mistaken, the Supreme Court has never decided the issue, nor have lower courts. They certainly didn't do it in Goldwater's case. On the bottom line, Sen. McCain is right, but not because of any Supreme Court precedent.

Many thanks to Prof. William Funk for pointing this out.

Supposedly Harmful Speech as Enjoinable Nuisance?

I just noticed a remarkable lawsuit, Wright v. Islamic Center; the plaintiffs were trying to enjoin the construction of a mosque. The theory? Construction of the mosque would be a "public nuisance," because the mosque would "spread radical Islam throughout the United States," would help make the county even more of "a haven for terrorists" than it was before, and thus create "a clear and present danger to the ... community." (The complaint also raises objections to the supposed extra traffic that the mosque's presence would cause, but that's not the core of the allegations.)

A creative tort law theory, and in my view entirely misplaced, both as a matter of substantive tort law and the First Amendment. If some people associated with the mosque have been engaged in speech that fits within some narrow exception to First Amendment protection, it should be punished for that speech. If they have committed some other crime, then they can be punished for committing that crime. But you can't enjoin a political or religious organization from erecting a building based on the organization's supposed past bad speech, just as it can't enjoin the publication of a newspaper based on the newspaper's supposed past libelous articles.

Fortunately, the plaintiffs have dropped the lawsuit, at least for now. Let's hope it stays dropped. Again, if the mosque founders have done something illegal, punish them for that; don't try to use the courts to shut up their religious teachings or block their religious buildings because they supposedly "spread radical Islam."

Liberals, Conservatives, and Free Speech:

A commenter writes, on the campaign finance speech restrictions post, Although suppression of speech has become a liberal monopoly, John McCain is one with the liberals on this, and he would readily appoint judges who would extend the range of suppressed political speech.

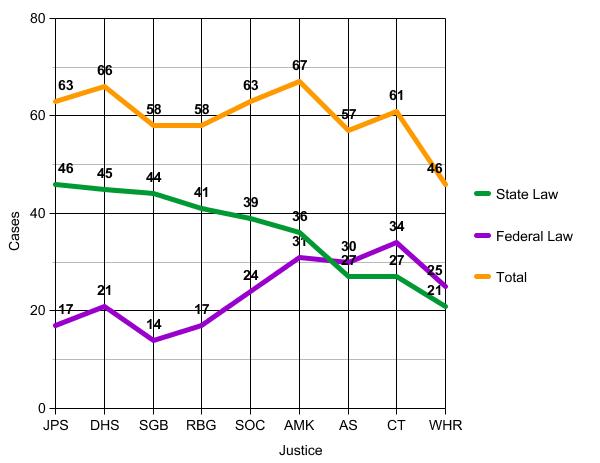

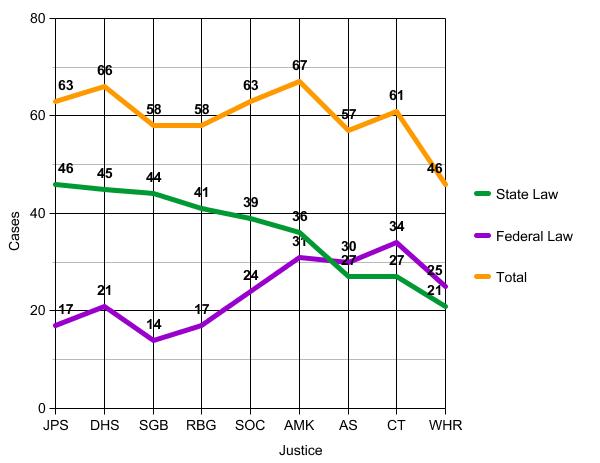

Let me say it again: Conservatives and liberals are both willing to restrict a considerable amount of speech (sometimes quite correctly, I might add). Neither side has a monopoly on speech restrictions. Consider, for instance, my study of how the Justices voted on free speech cases, 1994-2002, which counted their pro-speech-claimant votes, with some adjustments that I explain there (the cases since 2002 wouldn't, I think, affect the bottom line much):

| 1 | Kennedy | 74.5% |

| 2 (tie) | Thomas | 61.1% |

| Souter | 61.0% |

| 4 | Stevens | 55.7%

|

| 5 | Ginsburg | 53.6% |

| 6 | Scalia | 49.6% |

| 7 | O'Connor | 44.7% |

| 8 | Rehnquist | 41.8% |

| 9 | Breyer | 39.7% |

Some conservatives have broad views of free speech protections, some don't; likewise for some liberals. My sense is that the same true for politicians and academics as well.

What if one limits this just to expression that is generally seen as being on core political, religious, and social matters, and excludes, for instance, pornography and commercial advertising? I don't have the numbers on that, but I can talk about the big picture: - Conservative Justices tend to be more willing to protect some sorts of such speech, for instance paid-for speech in campaigns, speech by judicial candidates, religious speech within generally available government funding programs, or antiabortion picketing (though note that on this last one, even Chief Justice Rehnquist supported restrictions).

- Liberal Justices tend to be more willing to protect some other sorts of such speech, for instance speech by government employees, speech that reports on the contents of intercepted telephone communications, and anonymous political speech (though note that on this last one, even Justice Thomas supported protection).

- On other matters, the views tend to be split, for instance on flagburning (and before you say that flagburning isn't literally speech, remember that contributing money to candidates isn't literally speech, either).

So as to some kinds of speech, left-right generalizations are in large measure accurate, especially when one focuses on Supreme Court Justices. But if we're speaking of speech more broadly, or even just political speech, one can't claim that speech restrictions are the special preserve of either side.

Related Posts (on one page): - Dorf's Reply:

- Living Constitutionalism:

- Liberals, Conservatives, and Free Speech:

Law School Maternity Leave Policies:

A question to the law professors among our readers -- what are your school's maternity leave policies (or parental leave policies, if you have them)? Inquiring minds (though neither mine nor my wife's) want to know. Many thanks!

John McCain, the Election, and the Future of Restrictions on Use of Money for Campaign Speech:

I think many (though by no means all) restrictions on the use of money for campaign speech violate the First Amendment. I'm one of the few people who thinks Buckley v. Valeo is basically right, and contributions can generally be capped but expenditures (including corporate expenditures, a matter on which I disagree with the Court's Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce precedent) cannot be. This means I'm not as critical of Sen. McCain's views as some of my conservative and libertarian friends are, but I certainly find much to disagree with in his views.

Still, let's be realistic: On the Court today, the liberal Justices are the ones who are most likely to uphold a wide range of campaign finance speech restrictions; Stevens, Ginsburg, and Breyer have even suggested that they would uphold limits on independent expenditures, which in my view would violate the core of the First Amendment. And the conservative Justices, including the moderate conservative Kennedy, are the ones who are most likely to strike down a wide range of such restrictions.

Perhaps McCain will appoint Justices who will end up being more likely to uphold such restrictions. But I'm pretty sure that he won't be a single-issue appointer on this matter. He's likely to appoint noted figures from the conservative legal movement, who are culturally and ideologically predisposed to be at least mildly skeptical of such restrictions, and likely to be (at worst) in the middle on this issue -- where O'Connor and Rehnquist mostly were -- and more likely where Kennedy, Alito, Roberts, and perhaps even Scalia and Thomas are.

On the other hand, I suspect that either Clinton or Obama would likely appoint noted figures from the liberal legal movement, who are culturally and ideologically predisposed to be open to such restrictions, and be where Stevens, Ginsburg, and Breyer are, or (at best) in the middle of this issue, where Souter has generally been. So my hesitation about many campaign finance speech restrictions is a reason to support McCain (despite my disagreement with him) rather than to oppose him. He's surely not perfect in my book, certainly not on this issue. But I think he'll be better than the alternatives, and to me elections -- especially general elections -- are all about the best option, not the perfect one.

Prison + Mental Institution Incarceration Rate:

Apropos Orin's post, and the news story it refers to, I thought I'd remind readers about Bernard Harcourt's guest-blogging last year on how looking at the fraction of people incarcerated in prison or mental institutions offers a useful perspective. Here's the key graph from Harcourt's work:

Unless, I'm mistaken, this graph includes prisons but not jails. Related Posts (on one page): - Prison + Mental Institution Incarceration Rate:

- One Percent

One Percent

of American adults is now behind bars. The connection between the higher and higher incarceration rate and the lower and lower crime rate remains hotly disputed. Still, the incarceration rate is a remarkable and disturbing figure. (Hat tip: Kieran Healy)

Stuff White People Like:

Very funny. Thanks to Steve Kurtz for the pointer.

Strange Law Review Stories:

Over at Concurring Opinions, Nate Oman offers a helpful reminder to law review editors: If you want to publish an article, please notify the author.

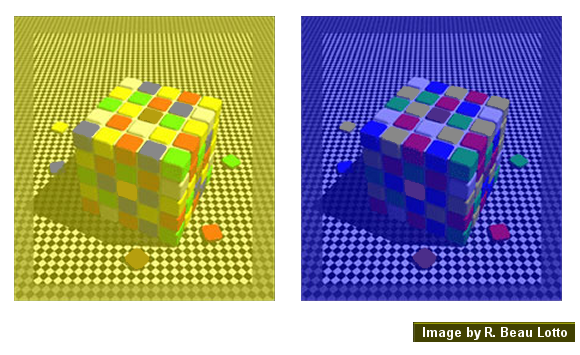

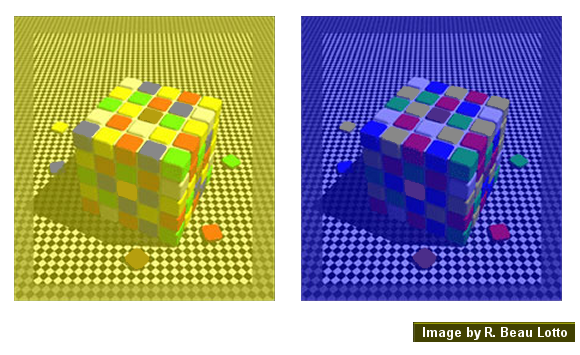

Cool Optical Illusions:

This blog displays lots of them, including my favorite, the color contrast illusion:

Would you believe that the seemingly blue tiles on top of the left cube and the seemingly yellow tiles on top of the right cube are actually identical? For proof, and more on this, see color the site. Check out the archives as well (linked to in the left margin, a few pages down).

UPDATE: Visitor Again wins.

Supreme Court Justices on Writing Opinions, the Role of Law Clerks, and Effective Advocacy:

Over at LawProse.Org, Bryan Garner has posted a remarkable set of extended interviews with eight of the nine current Supreme Court Justices (all but Souter) about legal writing, advocacy, and the process of deciding cases and writing opinions. The interviews are one-on-one, and each ranges from 30 minutes to over an hour. Justices Breyer, Ginsburg, and Thomas were interviewed in their chambers, and the rest appear to be in either the Lawyer's Lounge or the SG's room in the Court building. Garner conducted the interviews in 2006-07, although I don't know when he posted the files. For Supreme Court geeks, these interviews are a gold mine. The Justices discuss a wide range of topics including how they write opinions; the role of law clerks; tips for effective advocacy; what they look for in cert petitions; whether specialists or generalists are better advocates; what parts of briefs they read first; the differences between being a lower court judge and a Supreme Court Justice; and which Justices — and in some cases, which professors — they think are the best writers. Each discussion is tailored to the specific Justice. For example, much of the Roberts interview focuses on how he approached written and oral advocacy as a lawyer before he became a judge. (Tremendously valuable advice, I thought.) Anyway, it's all super cool stuff. Thanks to Roy Englert for the link. UPDATE: Those watching using Windows should right-click on the image, click "zoom," and then click "full screen". That brings the video to full size.

National Grammar Day:

Arnold Zwicky (Language Log) has many wise thoughts on the subject. Here's one, though you should read the whole post: [T]he assumption that non-standard variants are unclear and therefore impede communication ... is mostly just taken for granted, without any kind of defense -- in what way is "between you and I" less clear than "between you and me"? in what way is "all shook up" less clear than "all shaken up"? they're non-standard, certainly, but LESS CLEAR? -- and the occasional explanations of how particular non-standard usages are unclear don't survive scrutiny. Instead, it's just an article of faith that non-standard variants (and conversational, informal, and innovative variants, and variants restricted to certain geographic regions or social groups) are unclear, vague, sloppy, or lazy .... This has been my experience as well, not in all instances, of course, but in many: Often people complain about some (supposedly) novel usage, and assert that it's stripping the language of clarity or precision or useful distinctions, but on closer analysis the assertion proves to be unfounded.

Wednesday, February 27, 2008

Very Cool Bumper Sticker:

One of my students has a bumper sticker on her laptop that says: "Vote No on Directive 10-289." It looked like this t-shirt, without the smiley face.

What, Was William H. Taft Chopped Liver?:

Jeff Rosen: "over the course of history, former politicians have made not only the best chief justices--think of John Marshall, Charles Evans Hughes, and Earl Warren."

Fly Your Terrible Towels at Half Mast:

Myron Cope, the legendary voice of the Stillers, has passed away at the age of 79.

My particular Cope memory was listening to him during Plaxico Burress's first game with the Steelers, when Cope was unable after many tries to spit out his name. So he simply decided to refer to him as "Flex" for the rest of the game. What a great character.

Comments on McCain and the Jewish Vote:

Comments for that post aren't working, and I don't seem to be able to fix it. So, if you want to comment, you can do so here.

UPDATE: The short version of my previous post is, Bush got around 25% of the Jewish vote in 2004. There are reasons to believe that McCain will be more popular among Jews than was Bush, and that Obama will be less popular than was Kerry. Therefore, one can expect McCain to do better than Bush among Jewish voters. Please read the prior post for details before commenting. Related Posts (on one page): - Comments on McCain and the Jewish Vote:

- McCain and the Jewish Vote:

William F. Buckley and American Conservatism:

William F. Buckley, who passed away today, was a major figure in the history of American conservatism. Buckley was not a great original thinker; but he was an outstanding and extraordinarily successful intellectual organizer.

Buckley's most important achievement was the role he played in making conservatism intellectually respectable again. When he founded the National Review in 1955, conservatism was almost completely marginalized in the intellectual and academic world. Buckley and the talented writers he gathered at the Review played a key role in changing that. He did so in three ways that today's conservatives and libertarians would do well to keep in mind.

First, he distanced intellectual conservatism from the conspiracy-mongering and anti-Semitism which had been an important element of the pre-Buckley American right. For example, Buckley played a crucial role in banishing the conspiracy-oriented John Birch Society from the mainstream conservative movement.

Second, Buckley tried very hard to create a genial and friendly image for conservatism as opposed to one that projected anger, intolerance, and rage. This posture was a natural extension of Buckley's friendly personality. But, more importantly, he understood that it would be impossible for conservatives to be taken seriously in the liberal-dominated intellectual world without it.

Third, like his longtime associate Frank Meyer, Buckley was a strong believer in "fusionism," the alliance between conservatives and libertarians. He himself was a fusionist in his own thinking, albeit in a less systematic way than Meyer. On some issues that divide libertarians and conservatives, Buckley actually leaned to the libertarian side - notably in his longtime advocacy of drug legalization. Although the conservative-libertarian alliance contained serious tensions, neither group would have been able to achieve as much without it. Today, both conservatives and especially libertarians are increasingly disillusioned with the fusionist project. It remains to be seen whether it can survive.

Unfortunately, Buckley's far-sighted rejection of conspiracy theory and anti-Semitism was for a long time not matched by similar enlightenment on racial issues. Not only did the early National Review claim that federal intervention to protect black civil rights violated constitutional federalism principles; it also contended that Jim Crow segregation was actually a good and justifiable policy (see, for example, this 1957 editorial defending southern states' denial of black voting rights). In fairness, several of the early National Review writers were opposed to segregation and favored efforts to change it (especially at the state level). But the magazine's editorial line - set by Buckley - was generally segregationist. Buckley and some of his NR associates were far from the only 1950s conservatives with a blind spot on black civil rights; but they were particularly important because of their status as founders of the modern conservative intellectual movement.

By the late 1960s, Buckley and NR stopped defending segregation and embraced official color-blindness. However, their failure to fully repudiate and apologize for their earlier stance made the later embrace of color-blindness seem strategic rather than principled and fed liberal suspicions that conservative color-blindess is just a pretext for promoting white privilege under another name. Eventually, Buckley did - to his credit - acknowledge that he had been wrong and that federal intervention to protect black rights against state governments had been necessary; but by that time it was very difficult to reverse the harm caused by his earlier stance. Although later generations of conservative intellectuals had no part in NR's early embrace of segregationism and many are probably unaware that it ever happened, the issue continues to stain conservatism's reputation in the intellectual world. By all accounts, Buckley was personally tolerant in his attitude toward racial minorities; but his public record on racial issues for a long time failed to reflect that.

Despite this serious blind spot, Buckley left American conservatism in far better shape than he found it. On balance, his shortcomings were definitely outweighed by his achievements. Related Posts (on one page): - William F. Buckley and American Conservatism:

- William F. Buckley, Jr. (1925-2008):

Supreme Court Recusals Because of Stock Ownership:

The L.A. Times reports that the Exxon Valdez punitive damages case might yield a 4-4 division — with no precedent being set, and the lower court decision being affirmed — because "Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. withdrew because he holds Exxon stock." And indeed important cases have in the past yielded 4-4 deadlocks because one Justice owned stock in one of the companies.

This is a pretty bad result, it seems to me: An important issue will be unresolved, the Justices' time will be wasted, the parties' money will be wasted, and all over what is likely just a few thousand dollars' worth of investment.

Isn't there some better solution, even if we insist that a judge may not own even a small stake in one of the parties? For instance, if the problem is indeed just that the Justice owns actual stock (as opposed to owning a share in some fund that owns the stock), wouldn't it be much better for the Justice simply to sell the stock if certiorari is granted? This would presumably be little loss for the Justice, who could sell at market rates and lose just the commission (plus perhaps have some taxable capital gain that he might rather have deferred). Nor would the Justice have any enduring bias in favor of the company — it's not like the past stock ownership created or reflected an emotional relationship that persists even when the stock is sold. Or am I missing something here?

UPDATE: My colleague and corporations law maven Stephen Bainbridge has more. Also, to respond to some general comments: (1) I'd try to make this divestment-instead-of-recusal something of a rule, whether strictly binding or just followed as a matter of practice and precedent. (2) If there are insider trading objections to this (a matter discussed in the comments), I think the law should be amended to remove such objections; the minor insider-trading costs created by such behavior seem to me to be greatly outweighed by the benefits of letting Justices do their jobs.

(3) I realize that litigants generally aren't entitled to their day in the Supreme Court; but it still strikes me as unfair to litigants to cause them to spend a lot of money litigating the matter there, and then have the case end up 4-4 just because of happenstance. It's not a horrible unfairness, but it's something of an unfairness. And, more importantly, it also creates costs to the legal system -- generally, the grant of certiorari is triggered by the Court's judgment that there is uncertainty (say, a circuit split) that should be resolved for the benefit of future litigants and prospective litigants. If resolving that uncertainty is (all else being equal) a benefit, failing to resolve it tends to be a cost.

The legal availability of handguns makes for a better-prepared police force and a safer citizenry:

Ed Nowicki (head of the International Law Enforcement Educators and Trainers Association) and I explain why in an op-ed in today's Baltimore Sun. The Nowicki-Kopel amicus brief is here.

McCain and the Jewish Vote:

Ann Althouse deconstructs Obama's answers to questions about Louis Farrakhan and Rev. Jeremiah Wright here.

Which brings me to the subject of the Jewish vote in November.

Jewish Republicans overwhelmingly favored Rudy Giuliani for president, and as a pro-choice candidate--Jews overwhelmingly and strongly favor abortion rights--with strong ties to the New York Jewish community, he would have been a formidable competitor for the Jewish vote.

McCain, however, is a reasonably strong second choice. He starts with the base of the 20-25% of Jews who voted for Bush in 2004--Jewish Republicans plus Democrats and independents who favored Bush's tough "war on terror" and pro-Israel policies, which McCain can be expected to continue. McCain also has the advantage of having an outspoken Judeophilic brother, and the support of Senator Joe Lieberman, who is extremely popular among the Jewish moderate Democrats and independents from whom McCain can try to draw support. (Very liberal Jews, like other very liberal Americans, tend to loathe Lieberman, but McCain won't get their votes regardless).

To that, one can add another fraction of the Jewish vote that was turned off by Bush's close ties to the Christian right, his own evangelical Protestantism (which many Jews unfairly and ignorantly associate with anti-Semitism), his elite WASP upbringing (Jews don't like to vote for people who remind them of people who kept their parents out of their neighborhoods, schools, and country clubs), and general bicoastal snobbery against his persona. American politics turns to some extent on the degree a particular group feels "comfortable" with a candidate, and I suspect Jews will feel far more comfortable with McCain than with Bush.

Moreover, what one might call the quasi-libertarian wing of the Jewish community--socially liberal but economically conservative--will be up for grabs. On economic matters, both Democrats are running populist economic campaigns, and McCain, unlike Bush, has a reputation for fiscal prudence. The quasi-libertarian Jews have, I think, broken heavily Democratic because of the Bush Administration's close alliance with the Christian right on issues ranging from abortion to sex education to stem cell research. McCain is conservative on abortion, but the lack of overt religiosity in his persona and campaign will help him among Jews.

Finally, McCain has a reputation as a moderate Republican, and many Jews have been willing to vote for such individuals in recent years in local and state elections (think Guiliani, Riordan, etc.), especially when the Democratic candidate is perceived to be

very liberal.

So what percentage of the Jewish vote could McCain expect to get against Obama? If Obama winds up being perceived by many as implicitly hostile to the Jewish community's interests, he could do very poorly indeed. The same is true if the Republicans successfully paint Obama as a McGovernite. In 1972, Nixon received about 33% of the Jewish vote against McGovern (caveat: Nixon won in a landslide, which is unlikely to happen to McCain). In 1980, Carter, who was perceived by many Jews to be hostile, received 45%, against 40% for Reagan, and 15% for Anderson. One should keep in mind that voting Republican is much more accepted in the Jewish community today than it was back then, and the growing Russian and Orthodox Jewish communities are much more Republican than the Jewish community as a whole.

My best guess is that McCain starts with a base of 25-30% of the Jewish vote, which is probably all he'll get if Hillary Clinton manages to win the Democratic nomination, as Jews will expect a reprise of the very popular prior Clinton Administration. But Obama's close ties to the anti-Israel Farrakhan-buddy Rev. Wright, along with his very liberal views on War on Terror related issues, his extremely liberal economic positions that will turn off the quasi-libertarians, and his strong support among the elements of the Democratic Party most likely to blame our foreign policy woes on Israel and the "[Jewish] neocon cabal in the Bush Administration," suggests to me that McCain could easily get 40%. On the other hand, if McCain makes another idiotic comment along the lines of "the Constitution established the United States of America as a Christian nation," my projections will turn out to be overly optimistic.

UPDATE: Commenter "Stash" makes some good points in rebuttal:

I think DB leaves out one important aspect of the question, and, that is, Obama will agressively, and, I think, effectively campaign for Jewish votes. He has overcome supposed demographic barriers before.

He will give numerous assurances on Israel, but, probably equally important, he will be given very high marks for standing up to antisemitism in the Black community--as he did when he chided a Black audience for anti-semitism (and homophobia). And, on an emotional level, his debate answer that he would not be standing there were it not for Jewish civil rights workers who put their lives on the line in the 1960s will move a lot of people. When was the last time you heard a "Black leader" give the Jewish community its "props" for the prominent role it played in the civil rights movement without any ifs, ands or buts? In short, I think that if Obama uses his considerable political gift to campaign for the Jewish vote, he can do a lot to offset questions raised about some "secret agenda" and questionable associations.

It also seems plausible that given his popularity among Blacks and progressives generally, he could be effective in delegimatizing in these communities at least the more illegitimate criticisms of Israel and "the Lobby." In the debate, I think, he implied as much. Jews could very well see this (combined with assurances on Israel) as a very positive thing.

Speech on Your Dorm Room Door:

The North Carolina State Technician newspaper reports:

"No Blacks allowed White Room Only, Blacks next door," a sign on the door of an Avent Ferry Complex apartment read last Thursday [Feb. 14] ....

"It was referred to the University for disorderly conduct and racial harassment," [Chief of Campus Police Tom] Younce said....

The reporter told me (in response to my e-mail) that the sign was put up by the apartment's three residents. The apartment is in a school-run dorm.

The sign is repulsive (unless it's some joke that all the neighbors grasped as such, but that the administration somehow overreacted to), but it is constitutionally protected by the First Amendment against administrative punishment, whether on a "disorderly conduct" theory (which would presumably focus on the sign's general offensiveness and tendency to lead to hostility and possible fights) or on a "racial harassment" theory. The university could ban all signs on the outside of dorm room doors (though see this contrary view), but even in a "nonpublic forum" such as dorm room doors, it can't impose viewpoint-based bans that forbid racist speech but allow other speech. Nor does the narrow "fighting words" exception apply to speech like this, which isn't focused on a particular person.

One justification I heard for a possible ban on such signs is that the university can ban discrimination in housing, and therefore can ban signs that announce to students that they will be so discriminated against. But I'm not sure that a university could, even in its capacity as landlord, interfere with tenants' "intimate association" right to choose whom to allow into their living rooms (or bedrooms). And even if it constitutionally could have, I highly doubt that North Carolina State would impose such a shocking constraint on people's freedom of choice in whom to socialize with. If you don't want blacks, white, Scientologists, men, or anyone else in your home, it seems to me you should be free to make that choice. So if the university wants to defend the restriction on the grounds that they ban discrimination in choice of guests, I'd like to hear them do that — that would be even more scandalous than the punishment of the speech.

UPDATE: I inadvertently originally cast the last paragraph as if the university had already found the sign to be punishable; I've corrected this to reflect the fact that right now there's just a question whether the sign is punishable.

Ninth Circuit Judges on Supreme Court Reversal:

Two weeks ago, a panel of Ninth Circuit judges held oral argument at UC Berkeley School of Law. In a Q&A session following the oral argument, the three Judges (Noonan, Thomas, and Bybee) were asked to comment on the Ninth Circuit's reversal rate at the Supreme Court. Boalt student Patrick Bageant was there, and he blogged the exchange over at Nuts & Boalts as follows: Judge Noonan: "Typical numbers are 20 out of the 16 thousand cases that come before this court. Who is worrying? It's like being struck by lightning."

Judge Thomas: "Well, in that case I've been struck by lightning a time or two."

Judge Thomas: "It's largely a media myth. But you just take the reputation, like Dennis Rodman."

Judge Bybee: "We're the Dennis Rodman???"

Judge Thomas: "Yeah, we're like the bad boys of the federal circuit."

William F. Buckley, Jr. (1925-2008):

The AP reports that National Review founder William F. Buckley, Jr. died this morning at the age of 82. Kathryn Lopez has an initial comment on NRO here. the NYT obit is here.

The DEA's Prescription Drug Problem:

The Drug Enforcement Administration is concerned about the abuse of prescription drugs, but its solution may do more harm than good. Writing in today's WSJ, former FDA official Scott Gottleib explains that the DEA is threatening to interfere with medical practice decisions, to the detriment of many Americans who benefit from prescription drugs.

The Drug Enforcement Administration is, sensibly enough, targeting the small number of physicians who inappropriately prescribe drugs in violation of current laws, the "patients" who doctor shop for painkillers and hoard drugs to abuse or sell them, and the criminal diversion of these medications from pharmacies and distribution centers. But the DEA is also trying to influence clinical decisions about when these drugs are prescribed.

This is a mistake. Clinical issues are not the expertise of the DEA. Placing more restrictions on the legitimate prescribers can harm real patients and ethical physicians.

The McCain Matching Fund Mess:

Senator John McCain's presidential campaign seems to have gotten itself into a little campaign finance mess by initially pledging to accept public financing, in exchange for various spending limits, and then changing its mind. Former FEC Commissioner Brad Smith provides a good overview of the law and the issues here. It provides all the background you need to understand the story.

The wonderful irony of government involvement in funding political campaigns – that is, giving your tax dollars to candidates and parties to use for convention balloon drops, negative TV ads, and campaign robocalls – is that it actually increases the perception of corruption in politics and distracts from discussion of political issues. Rarely has this phenomenon been so clearly illustrated as in the current flap over whether or not Senator McCain is committed to using tax dollars – with accompanying spending limitations – prior to his formal nomination at the GOP Convention in September.

The other delicious irony is that there are few who can match McCain's fervor for strict enforcement of campaign finance laws. Any chance this experience will change his mind?

No Mohawks in Kindergarten:

A six-year-old boy has been suspended from a charter school kindergarten in Parma, Ohio, because he has a mohawk. As reported here, school officials concluded that his haircut distracted other students and was "disrpting the educational program" of the school. The boy's mother plans to enroll her son in another school rather than appeal the suspension.

Hamdan's Surprise Defense Witness:

I somehow missed this news last week: Col. Morris Davis, the former Gitmo prosecutor who resigned in protest of political interference with the military commissions (see these posts), expects to be called as a witness for the defense in the trial of Salim Ahmed Hamdan. If so, Davis is expected to testify that political interference has compromised the integrity and impartiality of the proceedings. The Defense Department may bar Davis from testifying, but as Kevin Jon Heller notes, such a move would be a "PR disaster."

Tuesday, February 26, 2008

The Case Against Government Subsidies for College Tuition:

The supposedly unbearable cost of college tuition is a hot issue in this year's presidential election. Both Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton include it in their stump speeches, as did some of the Republican candidates. Politicians are outbidding each other in proposing to increase various government subsidies for tuition payment. If government doesn't act, they claim, the middle class and the poor won't be able to afford to send their kids to college.

In reality, college is getting more affordable, not less, once you take into account the rapidly increasing income gains from getting a college degree. Far from being an essential way of helping the poor, government subsidies for college tuition are likely to harm them for the benefit of the relatively affluent.

I. The increasing benefits of college education are more than enough to pay the increasing costs.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Gary Becker has some important correctives to the conventional wisdom on the cost of college. It is indeed true that tuition rates have risen greatly over the last 30 years. But, as Becker notes, "the benefits from a college education in the form of higher earnings, better health, better educated children, and many other aspects of life have grown much faster than tuition has" (see also this excellent article by Becker and his colleague Kevin Murphy). This 2002 Census Bureau study shows that a worker with a bachelor's degree can expect to realize almost $1 million more in lifetime earnings than one with just a high school diploma. The same study shows that getting a master's or professional degree will increase your income still further (adding an additional $2.3 million in the case of a professional degree). And these figures don't include the additional income you can generate by investing some of that extra $1 to 3 million over the course of your life. If you invest even 5% of it at a reasonable rate of return, the power of compound interest will net you an additional several hundred thousand dollars of added wealth by the time you retire. The Census Bureau and Becker and Murphy both emphasize that the relative benefits of going to college have increased greatly over time, much faster than the increase in tuition costs.

Even at the most expensive private universities, four years of tuition, room, and board is unlikely to cost more than $180,000 or so (the approximate cost of four years at Harvard at maximum tuition rates). And, as Becker notes, many students (especially the poor) don't pay the full sticker price because of widely available financial aid and merit scholarships. The income gains of getting a higher education far outstrip the tuition. The vast majority of students can therefore afford to pay for college by borrowing against their future incomes, and still have an enormous income gain left over. Thus, there is no reason for government to subsidize college tuition on the grounds that it is "unaffordable" - even for those students who are unfortunate enough to have to bear the full cost themselves, without parental assistance.

II. What about college graduates who go into relatively low-paying professions?

Obviously, the $1 million figure is an average that won't hold true for every college graduate. What about those who enter relatively low-paying professions? In most cases, there is good reason for income disparities between professions: the lower-paying ones are less in demand. We want the market to channel more people to higher-paying professions for which there is more of a demand and fewer people to fields where the demand is relatively low. Subsidizing the low-paying fields by having the government subsidize college tuition undermines this efficient allocation of labor and makes us all worse off by channeling too many workers into the wrong fields.

But what if you think there is some market failure that leads to undesirably low salaries in a particular profession? Perhaps the market generates too many accountants and not enough artists. Even if you think this "problem" really exists, general subsidies for all college tuition are not the right solution. Rather, you should advocate targeted subsidies specifically for the artists (or whatever other profession you think the market undersupplies). There is no reason to subsidize those students who don't go into the undersupplied field where you think a market failure exists. Subsidizing all students indiscriminately won't do nearly as much to raise the number of artists because it won't create as much of an incentive to choose art over higher-paying fields.

It's important to remember that even income gains far below the average return to going to college are still more than sufficient to pay for tuition. For example, a college graduate who increases her lifetime earnings by "only" $400,000 (less than half the average gain) has still earned enough extra income to pay for tuition several times over.

III. How government tuition subsidies harm the truly poor.

Not only are government subsidies for government tuition unnecessary, they also victimize the truly disadvantaged people in our society: those who lack the educational qualifications to go to college in the first place (usually due to a combination of poor public schooling and a flawed family environment). These people pay some of the taxes that support subsidized tuition for college students who are likely to end up far wealthier than they are. They are also indirectly harmed by the diversion of public funds to tuition subsidies and away from other priorities that might do more to advance the interests of the truly poor. Government tuition subsidies are a classic example of a policy that redistributes wealth to the relatively affluent under the guise of helping the poor.

I don't mean to suggest that the high cost of college tuition is completely justified by increasing returns to education. In some cases, tuition has been artificially increased by government-imposed restraints on competition. In my own field of legal education, for example, tuition rates have been increased by restrictions on competition created by the American Bar Association accreditation requirement for law schools. This government-sponsored cartel has an obvious interest in raising the cost of legal education so as to reduce the influx of new lawyers who might compete with ABA members. Even in these cases, however, the right solution is not to subsidize law school tuition but to end the requirement of ABA accreditation and allow new law schools to compete with the incumbents, thereby driving tuition down to competitive market levels.

UPDATE: It's important to remember that proposals to aid students that merely subsidize their loans as opposed to give them straight grants also count as subsidies. If the loan program doesn't reduce the student's interest rate below what it would be in the private sector, there is no point to it. If it does, it's a subsidy that defrays at least part of the cost that the student would otherwise have to pay himself.

UPDATE #2: The Census Bureau figures likely overstate the true income gain from going to college in so far as some of the earnings difference between college graduates and high school graduates is likely due to differences between the two groups unrelated to education levels (e.g. - the average college graduate is likely smarter and more motivated than the average high school grad and so might earn a higher income even if he didn't go to college). However, even if the "real" income gain from going to college accounts for as little as one third or one half the pay differential between college grads and high school grads, it's still more than enough to pay for the tuition. Moreover, it's likely that the real gains are a much larger fraction of the difference than that. As Becker and Murphy point out, bachelors' degree holders today earn 70% more than high school graduates, compared to only 30% more in 1980. It's highly unlikely that today's college graduates are, on average, significantly smarter and more motivated than their predecessors of thirty years (or that today's high school grads are vastly dumber and lazier and their predecessors). Most of the relative gain is likely due to a higher real return on education. Finally, check out this study by Princeton economists Orley Ashenfelter and Cecilia Rouse, which shows that most of the income differences associated with additional years of education are in fact caused by the education itself rather than by other variables such as differences in ability and family background. The authors' estimate that each additional year of education increases the student's income by about 10%, even controlling for various background variables.

That Could Be a Mighty Expensive Light Bulb:

The Boston Globe reports:

The [study issued by the state of Maine and the Vermont-based Mercury Policy Project], which shattered 65 [compact fluorescent] bulbs to test air quality and clean-up methods made these recommendations: If a bulb breaks, get children and pets out of the room. Ventilate the room. Never use a vacuum -- even on a rug -- to clean up a compact fluorescent light. Instead, while wearing rubber gloves, use stiff paper such as index cards and tape to pick up pieces, then wipe the area with a wet wipe or damp paper towel. If there are young children or pregnant woman in the house, consider cutting out the piece of carpet where the bulb broke. Use a glass jar with a screw top to contain the shards and clean-up debris.

Cut out the piece of carpet? How expensive will that to be replace? I've seen reports that the mercury risk is greatly overstated, but this story worries me. The $2000 toxic cleanup bill story was apparently based on an overreaction; but if this study, which is hardly anti-fluorescent, is right, those bulbs might prove very costly.

As importantly, while it sounds like the mercury danger can be largely eliminated using these cleanup tips -- expensive as they can be when carpeting is involved -- there's always a risk that the cleanup won't be done exactly right: Say, for instance, that a child breaks the bulb, and doesn't follow proper cleanup procedures, or doesn't get out of the area promptly. Of course small children should be taught to leave the area of any glass breakage in any event, but the trouble with small children is that they don't always do as they're told; I don't like the idea of adding mercury poisoning risk to the risk of glass cuts.

And I say all this as someone who has largely replaced most of the standard incandescent bulbs in my house with fluorescent ones (though fortunately for me, we have wood floors in most of our house, so at least the carpet concern is absent). Perhaps I should have stuck with my normal skepticism about environmentalist enthusiasms. Or am I missing something?

Thanks to the Wall Street Journal's Best of the Web for the pointer.

Steven Teles' The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement:

Steven Teles' new book The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement is an important and insightful account of conservative and libertarian efforts to influence the law, legal institutions and the legal academy over the last 30 years. It does a good job of explaining the successes and failures of the institutions it discusses (primarily the Federalist Society, the Olin Foundation, and libertarian public interest law firms such as the Institute for Justice and the Center for Individual Rights).

As David Bernstein notes, the book is not a truly complete discussion of the subject implied by its title. Indeed, it is really more of a study of libertarian public interest organizations and academic movements than of the right of center legal movement more generally. With the exception of the Federalist Society (which, as Teles correctly notes, deliberately maintains "big tent" neutrality between libertarians and conservatives), most of the major institutions profiled in the book are either explicitly libertarian (such as IJ) or primarily focused on advancing the libertarian elements of the conservative agenda (such as CIR and various law and economics programs).

The book pays little attention to right of center legal institutions motivated primarily by religious considerations (such as Regent Law School, the Rutherford Institute, etc.) or to the social conservative backlash against liberal efforts to use the courts to protect "obscene" speech, extend abortion rights, and limit government "entanglement" with religion. Teles does note that these causes have gained relatively less ground in the academic and public interest worlds than libertarian ones and suggests that courts might be better vehicles for efforts to limit government power (as libertarians seek to do) than for efforts to expand or protect it (as social conservatives wish to do in those areas where they disagree with libertarians). This is an intriguing thesis, but warrants more systematic discussion than Teles is able to give it in this book. A greater focus on social conservative legal movements might have enriched Teles' analysis and provided him with a good comparative foil for assessing the more libertarian organizations he focuses on.