|

Saturday, June 20, 2009

White House says Obama Health Care Promises Should Not Be Taken Literally.

After President Obama’s big speech on health care, I was among the first to note that I couldn't see how he could possibly keep his promises. Now, according to the Associated Press, the White House has backed off Obama’s promises made just last Monday.

Here is part of my post last Monday:

In President Obama’s speech to the AMA, he made firm promises that I don’t think he can keep if his plan were to be enacted:

So let me begin by saying this: I know that there are millions of Americans who are content with their health care coverage - they like their plan and they value their relationship with their doctor. And that means that no matter how we reform health care, we will keep this promise: If you like your doctor, you will be able to keep your doctor. Period. If you like your health care plan, you will be able to keep your health care plan. Period. No one will take it away. No matter what. . . .

If you don’t like your health coverage or don’t have any insurance, you will have a chance to take part in what we’re calling a Health Insurance Exchange. . . .

If this goes through, many employers will do little different than they are today.

But if the Obama plan is enacted, a substantial portion of employers will cut their health subsidies — raising their employees’ share of contributions to the company plan — in order to drive some of the employees into the government exchange and the public option. Other employers may drop their plans altogether — after all, workers could buy their own coverage in the government exchange — or simply fund part of their workers’ participation in the exchange.

These changes, which would be the direct results of the implementation of the Obama plan, would make it virtually impossible for Obama to keep these promises: “If you like your doctor, you will be able to keep your doctor. Period. If you like your health care plan, you will be able to keep your health care plan. Period. No one will take it away. No matter what.”

Here is Mike Gonzalez at Heritage on Friday:

Less than 24 hours after Heritage Foundation President Ed Feulner questioned the veracity of President Obama’s persistent claim that, under his health care proposals, “if you like your insurance package you can keep it”, the White House has begun to walk the President’s claim back. Turns out he didn’t really mean it.

According to the Associated Press, “White House officials suggest the president’s rhetoric shouldn’t be taken literally: What Obama really means is that government isn’t about to barge in and force people to change insurance.”

How’s that for change you can believe in?

Depending on how the public plan is designed in Congress, millions of Americans would lose their existing coverage. By opening the public plan to all employees and using Medicare rates, the Lewin Group, a nationally prominent econometrics firm, has said that the public plan could result in 119.1 million Americans being transitioned out of private coverage, including employer based coverage, into a public plan. With employers making the key decision, millions of Americans could lose their private coverage, regardless of their personal preferences in this matter.

In other words, if you believed something closer to the opposite of what Obama promised, that would be closer to the truth. When Obama said he “will keep this promise”:

If you like your doctor, you will be able to keep your doctor. Period.

he actually meant:

If you like your doctor, many of you will NOT be able to keep your doctor. Period.

And when Obama said he “will keep this promise”:

If you like your health care plan, you will be able to keep your health care plan. Period. No one will take it away. No matter what.

Obama really meant:

If you like your health care plan, many – perhaps most – of you will NOT be able to keep your health care plan. Period. Someone – perhaps your employer – may take it away. It all depends on how things work out.

Related Posts (on one page): - White House says Obama Health Care Promises Should Not Be Taken Literally.

- Can Obama Keep His Most Emphatic Promises on Health Care?

Amos Guiora on the Israeli Administrative Detention Model:

Over at the international law blog Opinio Juris, Professor Amos Guiora has been offering a set of very interesting guest posts on the Israeli administrative detention model. Professor Guiora was an Israeli JAG officer for 19 years, and has a fascinating discussion going in the series. VC readers might find it interesting - certainly I do, and I raise a question to Professor Guiora at the end (to which he replies, here), what are the differences between the judicial role in Israel and the US, and how might they affect the applicability of such a model here. Given the important discussions being had by the administration and many others over Guantanamo, detention, national security courts, etc., this is an important body of interventions, and I recommend it to you. Go here and then scroll up to see all the various posts.

Update: I'm pleased to add that Harvard Law School professor Gabriella Blum has provided Opinio Juris with a substantive comment on the question of the judiciary in Israel and its role in counterterrorism, and comparisons with the United States. Very interesting comment sent by Professor Blum from Tel Aviv.

Let Marianne, Goddess of Liberty

smile upon the protestors. But like you, I have grave fears.

(Update: This op-ed by Jim Hoagland at the Washington Post captures my own overall view pretty well.)

I have no special expertise on Iran and so am only able to add my deep concern, sympathy, and support to the brave people in the streets seeking change in Iran. I also do understand that, from the US government's point of view, it all looks ... complicated. As indeed it is; I am far from indifferent to the concerns of realism and unanticpated consequences of events in places we barely understand.

Still, at this moment, I would hope that the United States government would not only support the specific rights of the protestors to peaceful assembly and free expression - but that it would say unequivocally that the United States stands for liberty and with those who seek it. Is that really so controversial or so hard?

Unable to sleep last night, I found myself picking up two books. The first is a now nearly forgotten Hungarian novel - yet one of the most compelling on the events of the European 20th century, George Konrad's The Loser (1982). I found myself reading the chapters on the Hungarian Revolution, its failure and the aftermath. But of course, the core of the Hungarian Revolution, as the chapter notes, is that it was a revolt less against one's own regime than against an outside imperial power, the Soviet Union.

The second is a book of poetry - short epigrams, passages, sketches from a journal - to which I have often returned in my life, Rene Char's Leaves of Hypnos (1946), his private journal from his years as a Resistance fighter in the Second World War. When I say Resistance fighter, I don't mean one of the "brave" French writers of those years, risking a 'no' from the censor, I mean someone who fought for years, rising to become the commander in charge of reconnaissance of that zone of southern France at the time of D-Day. (The translation to which I have linked at Amazon is by the very fine American poet, Cid Corman.) I found myself drawn to this passage, No. 22:

TO THE PRUDENT: It is snowing on the maquis and there's a perpetual chase after us. You whose house does not weep, with whom avarice crushes love, in the succession of hot days, your fire is only a male nurse. Too late. Your cancer has spoken. The country of your birth has no more powers.

The original French, sorry for the lack of diacritical marks:

AUX PRUDENTS: Il neige sur le maquis et c'est contre nous chasse perpetuelle. Vous dont la maison ne pleure pas, chez qui l'avarice ecrase l'amour, dans la succession des journees chaudes, votre feu n'est qu'un garde-malade. Trop tard. Votre cancer a parle. Le pays natal n'a plus de pouvoirs.

Let Marianne, the goddess of liberty, smile upon the protestors. Yet I hope I will not find myself going back to another passage from Char's poems, one of the justly most famous:

Bitter future, bitter future, a dance amongst the rosebushes ....

Update: Scrolling through the comments, it seems I wasn't sufficiently clear on a couple of points. First, I do take the realist concerns entirely seriously; that's why I raised the Hungarian revolution, and The Loser in particular, which has much discussion of the costs of failing. However, I am not convinced that raising liberty as something the United States supports as such is inconsistent with prudent realism. I do not think that general value is addressed by raising specific freedoms such as assembly or expression, as President Obama has done.

Second, I do not suggest that the administration acts in bad faith in making these difficult judgment calls between realism and idealism; I might well make them differently, but that's what presidents have to do. It is a function of being president, one might recall, however, that applied, or ought to have applied, equally to Bush, Clinton, and those who came before.

Third, if this is not the moment for the President to speak forthrightly on a general American commitment to liberty in the aspirations of oppressed people in the world - and I agree, it might not be, or at least that is a judgment an administration could certainly make in good faith - still, I should want to know under what conditions, if any, it would be appropriate for the President of the United States to express such a sentiment. I do not mean by this a merely general expression of support for liberty as a universal value, but rather that the United States is and has been committed to liberty as a value, and that it should be. If now is not the moment, as it possibly might not be - it would nonetheless be helpful to have some idea of the baseline for when it would be.

Some caution about Census data on same-sex couples:

Yesterday I posted some results from a new Census study comparing married same-sex couples and married opposite-sex couples, and comparing both to unmarried same-sex couples. The study concluded that in many significant ways — including likelihood to be raising children, income, home ownership, education, and race — gay and straight married couples were very similar, and unlike unmarried gay couples. The study also furnished evidence for some surprises, like the possibility that lesbian couples might be less likely to get married (or consider themselves married) than gay male couples.

But there's a potential problem in at least some of the Census numbers, which are inconsistent with some of the work done by demographers who have studied same-sex couples. Gary Gates, a noted demographer and researcher at UCLA (and a gay-marriage supporter), writes in an email to me:

One of the take-aways from the [Census] report is that married same-sex couples look quite a bit like their different-sex counterparts. That may very well be true, but one reason for the similarity is that it's quite possible that a very large portion of the married same-sex couples are, in fact, different-sex married couples who miscoded their sex. I've attached a paper (presented at the same session of the Population Association of America conference as the Census paper) that describes the difficulties in interpreting the married same-sex couple data.

From other work I've done, we know that married same-sex couples are 2-to-1 female and that women are more likely than men to be in a partnership. This isn't very consistent with the Census findings. Our analyses suggest that the sex miscoding problem among married different-sex couples creates more male same-sex couple miscodes than female. That could explain the Census findings.

There are several other findings that are not consistent with information we have about differences between cohabiting same-sex couples who are or are not in legally recognized relationships. For example, in a paper I published recently in Demography (with Christopher Carpenter), we show that those in registered domestic partnerships (in CA) ["RDPs"] have higher income and education levels and are more likely to be white than those who are not registered. These are the same patterns we see among heterosexual couples (comparing married v. unmarried) and contradict the Census findings. We also find no evidence of higher rates of child-rearing for those in RDPs in men and modest evidence of differences among women. Granted, RDP and marriage are not the same, but folks should be very cautious in interpreting the Census findings.

I think it's a very positive step that the Census released an analysis of the same-sex spouses. But it's just a first step. Much more work is needed to better understand who the married same-sex couples are and how many are miscodes.

If Gates is right about the coding problems, the miscoding would have skewed the results in favor of similarities since opposite-sex couples would have been included in the "same-sex" data. So gay and straight couples may be alike in many of the ways the Census Bureau suggested, but the new Census data do not necessarily support that hypothesis. A lot more work is needed, including more work based on the 2010 Census itself. In the meantime, modesty and caution about this new Census data are in order — more modesty and caution than I used yesterday.

UPDATE: For some interesting historical background on an especially noxious Census error, see here.

American Universities and the Nazis:

Inside Higher Ed has a story about controversy surrounding what strikes me as a curious book, The Third Reich and the Ivory Tower. I only glanced at the book, but according to the story, the book documents the fact that American universities maintained cordial ties with German universities and in some cases the German government until Kristallnacht in 1938.

What I find curious about this book is that while Germany from 1933 through 1938 treated Jews very badly, it wasn't until Kristallnacht that one could say that Germany was more vicious in its treatment of minorities than, say, Mississippi. American universities certainly weren't boycotting Mississippi, so it strikes me as an obvious issue of hindsight bias to argue that American universities that were exceedingly tolerant of domestic racism should be specifically excoriated for paying little attention to foreign anti-Semitism, just because in historical retrospect we know that German anti-Semitism led to the Holocaust. Not to mention that universities have generally (and usually properly) tried to stay out of political causes, absent extreme circumstances.

Of course, to the extent individuals in universities were sympathetic to the Nazis and their aims, and the book apparently discusses such individuals, they deserve individual condemnation, as do the likely much greater number of Stalinists who populated American academia. But substitute Communist for Nazi and Russian for German in the following sentence, and you will likely accused of promoting McCarthyism and anti-Communist hysteria, even though Stalin had killed far (far!) more people by 1938 than had Hitler: "but what is most alarming about the case is the administration's indifference to having an all-[Communist] [Russian] department at NJC, and the Rutgers' trustees' obvious hostility to committed opponents of [Communism]."

According to IHE, the author "criticizes American Catholic universities for keeping up friendly relations with Benito Mussolini's Fascist government, and also for their support of the Fascist General Francisco Franco in Spain." So universities are never supposed to have any relationships with dictatorships? Shall we cancel the visas of the thousands of Chinese students currently in the U.S.? What should we do about the many Latin American Studies professors, indeed populating entire departments, who are favorably inclined toward Castro? (BTW, given that the Spanish Republicans murdered around 7,000 priests and nuns, it's not surprising that Catholic universities, run by priests, preferred Franco.)

So, to sum up, I think (1) it's a curious feature of the U.S. that we like to focus on how Americans dealt with evil foreigners while we are much more reluctant to discuss how dealt with our own evils; (2) Nazi Germany had proven itself quite evil before 1938, but few people, including even many Nazis, anticipated what was to come, and it's unfair to treat people's reactions to Nazi Germany circa 1935 as if it they knew what Nazi Germany was going to be doing circa 1943--there's a big difference between various forms of official anti-Semitic harassment (though that was bad enough), which many, including many German Jews, thought or hoped was a passing phase as the Nazis consolidated power, and genocide. Fascist Italy and Franco's Spain were rather unremarkable dictatorships, and to argue that universities should have cut ties with them would mean that universities should cut ties with any dictatorship; and (3) it remains true that in most intellectual circles, even a whiff of cooperation with the Nazis identifies one as a bad person, but overt Stalinists are not only forgiven but often celebrated. (See, e.g., Paul Robeson, I.F. Stone, the Hollywood Ten. Bard College still has a professorship named for Stalinist Soviet spy Alger Hiss!)

Friday, June 19, 2009

"D.C. Expands List Of Allowed Guns To Avert Lawsuit,"

reports the Washington Post. "[Alan] Gura [who won the D.C. v. Heller case] filed another lawsuit in federal court in March on behalf of three individuals who wanted a handgun that wasn't on the District's list. To avoid that litigation, Attorney General Peter Nickles said the city decided to expand its list of legal weapons to include those listed on Maryland's and Massachusetts's "safe gun rosters."

Global Governance or Governmental Network Coordination for Global Financial Regulation?

Peter Mandelson, currently Business Secretary in the UK government of Gordon Brown and formerly EU trade commissioner, has an op-ed in today's WSJ (June 19, 2009), "We Need More Global Governance: The Crisis Reveals the Weakness of Nation-Based Regulation," (might be behind subscriber wall). (Reader warning: this goes on for a while.)

This piece offers a striking example of the intersection of substantive views of monetary policy affecting one’s policy views of what regulatory reform (in this case global regulatory reform) should mean. The explanatory gap I point out below in the piece goes beyond criticism about both the weakness of ideas of global governance, or the careful exploitation of strategic ambiguities in what the term is supposed to mean (one thing to me to get me on board, another thing to you to get you on board). It points in the direction that Ilya raised in his last post on this, to say that if you have one substantive economic view of the crisis, then you can propose that public governance bureaucracies can improve the situation; but if you have another, you have reasons to reach exactly the opposite conclusion.

Mandelson starts by offering a carefully phrased account of how the global financial crisis, next global recession, came about. He liberally spreads around the blame, without putting any of it on identifiable actors, all very diplomatically. However, his assessment of What Went Wrong finally lands on a very specific contention:

[W]hat enabled the banking crisis to happen was a structural imbalance in the growth model of the global economy over the last two decades.

That model has produced unprecedented global growth, but it also developed a serious weakness at its center. Unless we address that weakness, any other counter-recessionary strategy is palliative at best. The risk is that as the global economy slowly returns to growth, the urgency to address this fundamental problem will recede.

Reduced to its crudest form the problem was this: Credit was too cheap in the developed world. It was kept cheap by a number of factors. The commitment of China to an export-led growth model, matched by a willingness from rich-world consumers to keep spending, created persistent surpluses in China in particular.

Those surpluses were invested in developed-world debt, particularly the U.S., pushing down interest rates. That encouraged investors to look for riskier and riskier investments to increase their yield. It also encouraged people to buy houses they couldn't afford with the help of people who probably shouldn't have lent them the money in the first place. That debt was sold around the world. The end of the housing bubble revealed the risk in the system.

Note that the article signally fails to mention the policy of central bank policy, and in particular Fed policy, under Greenspan and later Bernanke, having allowed the money supply to rise too high and allowing interest rates to remain too low. When I first read the piece, I assumed that this was mere diplomacy on Mandelson's part. But, as it happens, the final substantive interpretation that Mandelson gives for ultimate causes takes an unequivocal position in the sharp debate over the role that monetary policy and central bank policy played in allowing the bubble to develop, and that in turn impacts his policy views. And in ways that draw in Ilya’s central contention from his last post directly.

This debate can be summed up as the argument between monetary economist John Taylor (Taylor of the "Taylor rule") of Stanford's Hoover Institution (full disclosure, with which I'm also affiliated) in a famous WSJ op-ed and a now widely read book, Getting Off Track (a 90 page read which you can get in hardback for $10 at Amazon; I know I’ve mentioned it before, adv.)), and Alan Greenspan, also responding in the WSJ as well as in his famously contrite Congressional testimony. The debate comes down to Taylor saying that the Fed goofed and Greenspan saying, no, there was a global savings glut about which the Fed could do not much. Mandelson comes down firmly on the side of Greenspan, with no suggestion that central bank policy might have served as a causally-necessary mediator for the transmission of the savings glut into easy credit, as at least an important part of the explanation of What Went Wrong.

This substantive commitment to ultimate causes (in one way explicit but in another way quite opaque, because it does not even acknowledge to the casual reader the debate of which it is one side) matters a great deal, as it turns out, to Mandelson's policy prescriptions. Consistent with the primacy of the global savings imbalance thesis, and conversely the unmentioned alternative primary explanation of central bank policy failures, Mandelson calls for a global regulator to address the systemic issue - not systemic risk, in the sense currently discussed, but instead global savings imbalances. He indirectly absolves the central bankers - let me stress, I am not interested in crucifying them or demonizing them, but the question of their mistakes directly poses the question of whether they plausibly can do that which Mandelson puts to them (emphasis added):

The stability or otherwise of the global economy is the sum of sovereign national macroeconomic policies. There is no mechanism to mediate between those policies or insist on action that would counter systemic risk. Similarly, national financial regulators have a clear enough remit for national market stability, but financial markets are now regional and global. Nobody was asleep at the wheel of globalization because there is no wheel to speak of.

Taylor would say that central bankers were asleep at the wheel, in failing, among other things, to follow the Taylor rule. Ilya would presumably say that it was not so much being asleep as that there is no good reason to think that central bankers are especially good at accomplishing this task. I would say that they were asleep at the wheel, they probably are not great at accomplishing this task, but that there are certain aspects of it that are best performed by regulatory actors, because expertise aside, there is a question of public fiduciary status for the market-establishing rules, rather than market-outcome rules. I would say those actors have to be national in character. Mandelson, however, insists that the global nature of what he sees as being the problem - a system that allows imbalances to develop - requires a global regulator, that is, global governance:

If these imbalances are to be unwound in an orderly way, China will have to build a social welfare system that reduces huge levels of precautionary saving and thus boost domestic demand. It will need to continue to move towards greater currency flexibility. The export-led growth models of other surplus economies such as Germany and Japan are also both going to have to give way to greater domestic demand. Both consumers and governments in the U.S. and Britain are going to have to repair their balance sheets. We are going to have to save and invest more and export more.

Is any of this actually possible? Is it possible to preserve the benefits of open trade and an open global economy, addressing macroeconomic risk while totally respecting the choices of sovereign governments?

The answer has to be: not really. No government in the global economy, and certainly not economies on the scale of the U.S., China, Japan and the European Union, can claim a prerogative over domestic action that entirely ignores the systemic affects of its policies. The only way forward is a totally renovated approach to international coordination of economic policy.

An odd contradiction emerges tacitly in the above passage. The op-ed speaks of “global governance.” But it then frames policy as a matter of “international coordination.” Later in the op-ed Mandelson again refers to this global governance as consisting of “much greater global coordination.” Is there a difference here worth mentioning? Well, governance is one of those terms, like multilateral, that can be used in strategically ambiguous ways - as noted above, it can be used to mean one thing to one player and another thing to another.

Put simply, what Mandelson seems to think is required is “global governance” in some supra-national sense, some regulator with power over all the others. But what he proposes is a different creature entirely - something that seems to indicate the “global government regulators network” model that Anne-Marie Slaughter has made famous (read a review nearly as long as the book, here), but ultimately a creature of coordination in which “peer pressure” on the model of trade regimes “is going to be vital.”

We are now back at a familiar conundrum in international economic law - networks without independent enforcement powers, subject to the familiar game theory problems of free riding, insincere promising, and defection. It is true, certainly, that such arrangements have been (on my reckoning) remarkably successful at finding ways to keep players from defecting in the large scale trade regimes (although no one should be too sanguine about the erosion of free trade in the current global recession). Sophisticated new game theorists of international economic law have been elaborating ways in which cooperation games can work in these arenas, moreover, and although I do not think they have much application in such areas as international security, I think they have promise in trade and economic relations. David Zaring, Kal Raustiala, and Pierre-Hugues Verdier, among others, have all written very interesting and important academic work on the promises and limits of networked government regulators in the global economy.

That said, there is an important - to my mind fatal - elision here, the oft-fatal elision seemingly [sorry Eugene!] endemic to international law discussions in this as in other areas in which governance, multilateralism, engagement, and such activities are at issue: you seek a way to bridge the chasm but the only way to do so is by reach to a concept, a term, a rubric that allows you to assert two things at once, often to different audiences. We need global governance to, well, govern things; we need global governance to, well, coordinate things. They are not the same thing, and the claims are addressed frequently to different constituencies whose political support is important. Eventually the inconsistency is exposed and you fall into the depths, because it is not merely a matter of terminology, but a term that one has used to signify two quite distinct courses of action.

These distinct courses of action are dependent upon distinct bases of authority, legitimacy, and power. Mistaking one for the other is, once again, politically attractive when trying to formulate a workable policy at the front end, but eventually causes one to fall into the abyss when the kind of action required by policy depends upon an actor lacking the kind of political authority, legitimacy, and power to do so: networks are not truly governing bodies, which was the point of creating them as networks, and most of the time that becomes especially true in a crisis. There are some important exceptions - one can point to the trade regimes, and one can point to the prestige of an otherwise powerless WHO in bringing about a globally coordinated response to pandemic disease. (So far; the day is still young, and WHO has not yet been tested in a true crisis in which free riding became a matter of life and death for large numbers of people to whom sovereigns are accountable.)

So far I have questioned Mandelson’s explanation of the crisis, or at least questioned his failure to acknowledge the rest of the substantive debate, and suggested that his substantive commitment largely determines his preferred policy or, more precisely, his preferred actor for policy. I have also questioned the gap between the coercive strength of governance that his substantive take on the problem might be understood to imply, and the merely coordinating body and activity that, presumably taking account of political reality, actually proposes. But now consider what specific global body Mandelson thinks should take on this role, and on what basis. It is, to say the least, remarkable:

We need to strengthen and depoliticize the International Monetary Fund and give it a new surveillance role that covers all aspects of systemic risk. It needs to be mandated to make recommendations on weaknesses in the system, and countries should be obliged to take these recommendations extremely seriously.

The IMF? Mandelson makes no mention of another debated question over the reason for the global savings glut. He implies that it is on account of the lack of social security, pensions, and such public structures in Asia and China in particular that force high private savings rates and dampen consumption - a huge factor I do not doubt in the least. However, he fails to mention that view that the lesson Asian governments took away from the Asian crisis of the late 1990s was ... never trust the IMF, and as government policy - not private savings policy - hold so much in governmental reserves that the currency markets can never take you on. Whether that explanation is right or wrong, or how important it is as an explanation - I myself am agnostic - it cannot be left aside in assessing institutions that might provide regulatory oversight. Ilya’s point again - if it is the case that the IMF got it massively wrong in the 1990s, not just for the economies of Asia way back when, but in ways that have substantially contributed to global misalignments of savings today, on what grounds does one suggest that it or any similar institution has any special ability to do a better job now?

The argument that the IMF, or really any public body, is the right body to do it depends not only on the assumption of expertise - that is, that as a fiduciary it is capable of exercising a substantively meaningful duty of care on this topic - but also on the assumption that it is a universal body that owes, and will exhibit, a duty of loyalty to everyone. Ilya has challenged the first, expertise or duty of care, assumption. Let me also challenge the second, universal or duty of loyalty, assumption.

Another example of strategic ambiguity is the presumed identification of “universal” with “international” or “global.” The hidden assumption is that the global and international are universal, and to the extent they have “interests,” those interests are by definition not parochial, partial, merely national. Whereas that assumption leaves aside the possibility both that beneath the language of universality lies an entire web of interests and parochialisms, as public choice theory would teach us; and, moreover, the possibility that the “international” and the “global” have their own set of interests, the interests of those who spend their time in the jet-stream between New York and Geneva.

We thus cannot assume that just because it is the IMF - international organization with a heroically worded charter, etc., etc. - that it has the interests of the world’s people (whatever that abstraction might conceivably mean) at heart. Indeed, effective and expert policy might depend upon the organization not being “representative” of the people whose interests it is supposed to universalize. And this goes to the heart of a separate, weltering debate that is starting to intersect with the global financial regulation debate: should the IMF and the World Bank be reformed so as to give greater, perhaps even proportionate, governance say to those affected by the institutions’ policies - rather than leaving it in the hands, as a shareholding institution, of the countries that provide the funding?

Whatever modest effectiveness, if any, the IMF and the World Bank have had in their decades of existence is owed in considerable part, in my estimation, to the fact that the donors call the tune and have board seats in proportion to their funding. Any move to alter that introduces the usual problem of moral hazard, which is to say, in UN terms, it risks turning governance of these organizations into the General Assembly, in which the 90% or so of the money spent by 190 or so countries is provided by about 10 of them. But this puts me on the wrong side of the powerful movement to reform these institutions.

And this only touches on the many deep governance and political and mission issues that underlie the IMF at this moment. (One of those, which I do not take a position on here, though I am not hostile to it, is the new funding currently before Congress for the IMF to provide it with funds to serve as the receiver, as it were, for basket case second-world economies such as Latvia; there are virtues in this plan, but in that case, one needs to decide what one thought of the IMF’s expertise, judgment, and policies in the Asian crisis.)

Mandelson implicitly recognizes there is a gap here. So he says, remarkably, that we need to “depoliticize” the IMF to enable to serve in this new role even as we “strengthen" it. Leave aside the controversies that faced the IMF as matters of governance before the financial crisis arose - all of them involved, however, not depoliticization, but questions of governance that would inevitably make it ever more political. Inevitably and, one wants to, of course. Mandelson's is a genuinely astounding formulation - Mandelson proposes global governance, and proposes the IMF, and then proposes that it be somehow depoliticized: what is governance of the political economy if not political? After all, the strongest proposal for the IMF yet - one that Mandelson does not broach and it is not clear what he thinks of it - is that the IMF, through its special drawing rights, become the world’s central banker. A worse idea, from the standpoint of fiat money and moral hazard, is hard to imagine, but that has been offered as a proposal, and not merely by the unserious.

Mandelson limits himself to proposing the IMF have a ”surveillance“ role - not necessarily a bad idea, on its own - and the power to make recommendations that countries must take ”extremely seriously.“ We know that when diplomats say ”extremely seriously,“ they typically mean nothing of the kind. That is, of course, the likely realist outcome of this kind of attempt to bridge multiple chasms. But more interesting than the usual problems that the facts of the real world pose for ideal solutions is that Mandelson insists, right to the end, of the strategic ambiguity of actual "governance" and "mere" coordination.

I’ve said that you can’t finally have it both ways. But the temptation is to go after the more modest version in the hopes of converting it into the stronger version down the road. (I've written about this as a problem for the UN.) That’s finally how the inconsistency is overcome - governance will mean mere coordination today, but real governance tomorrow. Yet the two remain different ideas, different in kind and not just degree, dependent upon different sources, as said above, of authority, legitimacy, and power, and the biggest risk is that you warp out of shape the modestly practical possibilities of ”mere“ coordination by a body such as the IMF because you are holding out for what you hope it might become as a body of true ”governance“ in the future. It is holding out for this possibility that seems to me to explain Mandelson’s insistence on using strategically ambiguous language. It allows him to offer as consistent a project that is, finally, inconsistent.

New Census study comparing gay and straight married couples:

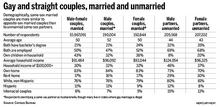

Gay and straight married couples are demographically very similar in terms of likelihood to be raising children, age, income, race, whether they own or rent a home together, education levels, and employment. And both are unlike unmarried same-sex partners (and, I suspect, unmarried straight couples), who skew younger, more educated, more wealthy, are much less likely to be raising children, and are much less likely to have invested in a home together.

That's what the Census Bureau has concluded based on a sample of same-sex couples who live together and self-report as married, although the Census Bureau does not verify whether couples (gay or straight) are legally married.

Here's the Census Bureau chart, which you can enlarge by clicking on it:

If you can't see it well above, you can find it here.

There are many fascinating results here, only a couple of which I want to highlight now.

The data about child-raising is especially significant since one common argument in the SSM debate is that marriage is centrally about providing a stable environment for children. Straight married couples are somewhat more likely to be raising children (43%) than are lesbian married couples (38%) or gay-male married couples (32%). But the difference is not huge, and separates all three categories from unmarried couples, gay and straight, who are far more likely to be childless. And while lesbian married couples are more likely to be raising children, the difference between them and gay-male couples is not nearly as large as commonly thought.

Also, a higher proportion of gay male couples are married (or consider themselves married) than are lesbian couples (52% of gay male couples v. 42% of lesbian couples). Among other things, this means proportionately more lesbian than gay male couples are raising children outside of marriage (20% v. 8%).

The debate over gay marriage is moving from the abstract to the empirical. That's especially true as more states gain more experience with actual gay marriages. Unfortunately, the Census Bureau has resisted including gay married couples in the decennial census, arguing that DOMA forbids it. I'm not sure that's right, though of course the existence of DOMA didn't stop the Census Bureau from collecting this data. (UPDATE: The Wall Street Journal says the White House has now abandoned that interpretation of DOMA and is directing the Census Bureau to find ways to include same-sex married couples in the 2010 census.)

None of this demographic information proves that gay marriage "caused" anything in particular. Among other things, it seems likely that gay couples who fit a traditional profile (have children, own a home) are more likely to get married than those who don't. And of course it doesn't resolve the debate over whether states should permit gay couples to marry.

But it does fill in some important missing information about what gay families and gay marriages look like. And it turns out that, in some significant respects at least, they look a lot like traditional ones.

(HT: iMAPP)

UPDATE: Some caution about this Census data, here.

Related Posts (on one page): - Some caution about Census data on same-sex couples:

- New Census study comparing gay and straight married couples:

A Constitutional History Danger:

Legal scholars and historians frequently make sweeping conclusions about the Supreme Court and its individual Justices based on votes in particular cases. The problem is that until relatively recently, the norms on the Supreme Court discouraged dissent, and the Justices may at certain times have had additional reasons beyond those norms for joining a majority opinion they disagreed with.

I've been working on chapter 4 of my book-in-progress, Rehabilitating Lochner. This chapter deals with protective labor laws for women, and liberty of contract challenges to such laws. In 1923, the Supreme Court invalidated a minimum wage for women in a 5-4 vote (Adkins v. Children's Hospital), but a year later the Court unanimously upheld a ban on night work by women (Radice v. New York).

The apparent inconsistency in these cases has led scholars to explain the discrepancy in a variety of ways, none of them complimentary to the Justices. One obvious but generally overlooked possible explanation is that in the night work case, the Court felt bound by a 1908 precedent (Muller v. Oregon) upholding a maximum hours law for women on the grounds that women are physically weaker than men, a rationale that simply did not apply to the minimum wage law.

But I just stumbled across something another interesting explanation. According to Felix Frankfurter's notes of a conversation he had with Justice Louis Brandeis, Brandeis told him that Radice almost came out the other way, but Justice George Sutherland, who had written the Adkins opinion, switched his vote at the last minute after agonizing over the case for some time. The other Justices still thought the night work ban unconstitutional, but with the Supreme Court under attack (most notably by future Progressive Party candidate Robert LaFollette and Senator William Borah) for issuing controversial 5-4 opinions, and with Sutherland having jumped ship, the other Justices chose not to issue a dissent.

Assuming that Frankfurter's notes accurately describe what went on, instead of a 5-3 vote (with Brandeis recused) split on women's protective laws turning a year later into a nine to zero vote, the 5-3 (plus Brandeis) split was apparently turned into a 5-4 split the other way, with the deciding Justice on the fence in the second case until the last minute.

So, for example, the view expressed by some scholars that the Court invalidated the minimum wage law but not the night work ban because the former allowed corporations to exploit workers through underpayment but the latter did not could only be justified if one could show that this was Justice Sutherland's rationale. But this would be a caricature of Sutherland, who believed in liberty of contract, and was a strong advocate of women's rights, but had an occasional soft spot for what he considered public-spirited regulation, as evidence by his majority opinion upholding zoning laws in Euclid v. Ambler Realty.

In short, if you want to do good constitutional history, don't extrapolate wildly from the reported votes of old Supreme Court cases.

Left/Right Bloggers in accord on grades for Obama WH staff, but not for his Econ. and Nat. Security Teams:

This week's National Journal poll of top political bloggers asked for performance grades thus far for various components of the Obama team. Regarding the White House staff, the Left/Right gap was fairly small, with the Left collectively assigning a B-, while the Right gave a C. I gave the staff a B, and wrote: "Although it's hard to tell from the outside, the staff seems to be working together well in managing the administration."

Bloggers were also asked to grade the Economic Team and the National Security Team. The Left gave the Econ Team a C+, and the National Security Team a B-. The Right gave an F in Econ, and a D in National Security. I voted for a D in both, and wrote: "Out-of-control spending, with massive debt financed by a radical expansion in the money supply. Timid on Iran, aggressive against Israel, self-deluded on the Palestinian desire for peace, and miserable handling of relationships with European governments."

If You Don't Want An Annoying But Extremely Catchy

theme song going through your head all day, don't watch the Pajanimals with your kids.

No, Not That David Bernstein:

I received a voice mail and email message asking me, "Are you the David Bernstein who is involved with the Moroccan clementine market?"

No.

Consumer Reports Rates Digital Cameras.

In its July issue, Consumer Reports (subscription required for full content) updated its online ratings of digital cameras.

From the site Product Reviews and Bargains, here is a list of some of the top choices :

For advanced Single Lens Reflex cameras (SLRs), [Consumer Reports] recommends the

Nikon D300,

Canon EOS 40D, and

Olympus E-3.

Most of the recommended point-and-shoot models are Canon PowerShots:

Among the recommended models in various categories of point-and-shoot cameras are the

Canon PowerShot SD1200 IS,

Canon PowerShot A470,

Canon PowerShot G10,

Canon PowerShot SX10 IS,

Samsung HZ10W, and

Fujifilm FinePix F200EXR.

Thursday, June 18, 2009

Rare (Partial) Victory in Second Amendment Case:

A federal court holds that someone being prosecuted for possessing a gun after having been convicted of a domestic violence misdemeanor is constitutionally entitled to present an affirmative defense "that he posed no prospective risk of violence" (which I take it must mean no prospective risk of violence beyond that posed by the average person). The jury would thus be instructed that, if it agrees with the defendant that he posed no prospective risk of violence, it should acquit despite the flat prohibition imposed by the statute.

Here is the meat of the opinion, U.S. v. Engstrum (Stewart, D.J.) (June 15, 2009):

This matter is before the Court on Defendant's Motion for Jury Instruction regarding his possession of a firearm. The Court previously denied Defendant's Motion to Dismiss Indictment, in which Defendant argued that the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protected his right to have a firearm in his house for home and self defense. In its April 17, 2009 Order, the Court found that strict scrutiny was required to justify a deprivation of an individual's Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms. The Court also found that 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(9), which prohibits the possession of firearms by those previously convicted of a domestic violence misdemeanor, passed strict scrutiny. Finally, the Court found that § 922(g)(9) was, therefore, presumptively lawful, but that the presumption could be rebutted by a showing that the individual charged under § 922(g)(9) posed no prospective risk of violence. With regard to the Defendant, the Court found that it could not say, as a matter of law, that the Defendant posed no prospective risk of violence.

Defendant concedes that he is a restricted person, otherwise covered by § 922(g)(9). In May 2008, Defendant and his girlfriend (the "Girlfriend") were residing at a home in West Valley City, Utah (the "Residence"). On May 9, 2008, Defendant and the Girlfriend got into an argument and the Girlfriend left the Residence. On May 10, 2008, the Girlfriend returned with the police to retrieve her personal belongings, accompanied by a friend, who waited outside the Residence while the Girlfriend entered to retrieve her belongings. Defendant refused to return her things, and an argument ensued. During that argument, Defendant grabbed the Girlfriend's arm, and the Girlfriend claims she feared for her safety. The Girlfriend attempted to use pepper spray on the Defendant, but the canister did not work. Defendant took the pepper spray away from the Girlfriend and was successful in using it on her. The Girlfriend then left the Residence and called the police.

When police arrived at the Residence, the Girlfriend informed them that Defendant kept a gun in his bedroom, although the gun was never used or displayed in any way by the Defendant prior to the police arriving. Defendant allowed the police to enter the Residence, where one officer noticed an unspent round on the floor of the Residence. When officers inquired about the gun, Defendant advised them that it was in his bedroom dresser drawer, and that he had unloaded it when he learned that law enforcement would be arriving at the Residence. The officers found the unloaded gun from the bedroom dresser drawer. The gun was not taken from the Residence at that time.

On May 22, 2008, West Valley Police contacted Defendant and inquired about the gun. Defendant indicated that he owned the gun and that it was a gift from his father. There is no evidence to indicate that Defendant had ever used the firearm. However, Defendant was advised that he could not have a gun due to a prior misdemeanor domestic violence conviction. Defendant indicated to police that he would surrender the gun and ammunition. Police arrived at the Residence later that day and Defendant signed a consent to search form and surrendered the gun and ammunition....

The Court finds that Defendant may raise, as an affirmative defense, that the charged offense may not be applied to him because he posed no prospective risk of violence. Such a defense is in keeping with the law stated in the Court's April 17, 2009 Order. The Court also finds that the affirmative defense raised by Defendant does not negate any element of the offense charged. Therefore, while the government must prove every element of the charged offense beyond a reasonable doubt, if Defendant chooses to argue that he posed no prospective risk of violence, Defendant will bear the burden of proving his defense to the jury by a preponderance of the evidence. However, the defense must be supported by sufficient evidence. Therefore, the Court will only instruct the jury on Defendant's defense if the Court finds that, during the course of trial, Defendant has presented sufficient evidence to convince a reasonable jury that he does not pose a prospective risk of violence. In the event that Defendant meets that burden, the Court will instruct the jury regarding Defendant's proposed Second Amendment defense in the following terms:

The Second Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees the fundamental right of individuals to keep and bear arms. That right may only be infringed when the restriction is narrowly tailored to meet a compelling government interest. You are instructed that 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(9), the crime for which Defendant is charged, is, as a matter of law, a lawful and constitutional restriction of the Second Amendment rights of those who pose a prospective, or future, risk of violence.

If you find that the government has proved beyond a reasonable doubt the elements of the charge against him, as set forth in Jury Instruction Number ____, regarding Count I, you are instructed that Defendant is presumed to pose a prospective risk of violence. However, Defendant is entitled to offer evidence to rebut that presumption and show that he did not pose a prospective risk of violence. It is the burden of the Defendant to prove to you, by a preponderance of the evidence, that he did not pose a prospective risk of violence.

Therefore, if you find that the Defendant did not pose a prospective risk of violence, he may not be deprived of his Second Amendment rights, and you must find him not guilty.

However, if you find that the government has proved beyond a reasonable doubt the elements of the charge against him, and that the Defendant has not proved, by a preponderance of the evidence, that he posed no prospective risk of violence, you must find the Defendant guilty.

By the way, all I could find from Pacer about Engstrum's past domestic violence misdemeanor conviction was that it was a "domestic violence assault" that had happened in "Midvale Justice Court in 2007." (The statement of facts above describes only the conduct that led to the discovery of the gun, but it was the 2007 conviction that caused Engstrum to be prosecuted for "possession of firearms by those previously convicted of a domestic violence misdemeanor.") Presumably the jury would be told about the circumstances of this past conviction, as well as about other things, in determining whether Engstrum indeed "pose[d] a prospective risk of violence" at the time of possessing the gun.

What Happens in a Multipolar World?

The Chicago Journal of International Law has a new symposium issue coming online soon on the topic of a multipolar world. I have a piece in it, so does my co-blogger Chris Borgen of Opinio Juris, John Yoo, and some others - I'll post a link to the issue when it appears. My own piece is titled, United Nations Collective Security and the United States Security Guarantee in a Multipolar World: The Security Council as the Talking Shop of the Nations.

It's a pretty self-explanatory title. The one thing I'd add to the abstract is that there is a discussion of NATO and a Hymn to one of my Intellectual Heroes, Raymond Aron, in the middle of the essay that begins (the editors were slightly taken aback): "Be wary, O Europe, and consider carefully what Aron would say of an America that does not assert, rudely and brusquely and vulgarly, its own interests first ..." Mighty pretty speechifying, no?

In shameless self-promotion mode, you can get it from SSRN at the link; here is the abstract:

This essay considers the respective roles of the United Nations and the United States in a world of rising multipolarity and rising new (or old) Great Powers. It asks why UN collective security as a concept persists, despite the well-known failures, both practical and theoretical, and why it remains anchored to the UN Security Council. The persistence is owed, according to the essay, to the fact of a parallel US security guarantee that offers much of the world (in descending degrees starting with NATO and close US allies such as Japan, but even extending to non-allies and even enemies who benefit from a loose US hegemony in the global commons such as freedom of the seas (leaving aside pirates)) important security benefits not otherwise easily obtained.

Much of the world can afford to pay lip service to UN collective security as an ideal, and to nourish it as a Platonic form, precisely because they do not have to depend upon it in fact. Not all the world falls within even the broadest conception of the US security umbrella, however, and these places include such locales as Darfur and other conflict zones in Africa. In those places, according to the paper, the US should engage with UN collective security to offer what the US will not, or cannot, offer directly.

The paper also argues that the Security Council should be understood, in a world of rising multipolarity especially, not as the "management committee of our fledgling collective security system," as Kofi Annan put it, or even as a concert of the Great Powers, but as simply the security talking shop of the Great Powers. Sometimes the Security Council can act as a collective security device, and sometimes as a concert of the Great Powers (e.g., the first Gulf War), but the condition of multipolarity argues that Great Powers are competitive and that the Security Council will find its limits, but also its role, mostly as the place for debate and argument, diplomacy successful or not - but not management of global security.

The essay also argues that those who want to see an end to loose US hegemony in favor of the supposed freedoms and sovereign equality of a multipolar world should think carefully about what they wish for. The dreams of global governance by international institutions turn out to have their greatest possibilities precisely in a world that, to a large extent, relies upon a parallel hegemon rather than collective institutions for its underlying order. In a multipolar, more competitive world, the winner is unlikely to be liberal internationalist global governance or UN Platonism or collective security, but instead the narrow, often directly commercial, interests of rising new powers such as China. The paper closes with policy advice to the United States on what it means and how it should - and should not - engage with the UN on security and the Security Council.

(The paper runs some 15,000 words and is part of a special symposium issue on a multipolar world.)

Court Strikes Down Random Drug Test Policy for All Public School Employees:

From Jones v. Graham County Bd. of Educ. (N.C. Ct. App. June 2) (some paragraph breaks added), an interesting discussion of the issue:

We first address Plaintiffs' contention that the policy violates Article I, Section 20 of the North Carolina Constitution, which provides as follows:

General warrants, whereby any officer or other person may be commanded to search suspected places without evidence of the act committed, or to seize any person or persons not named, whose offense is not particularly described and supported by evidence, are dangerous to liberty and shall not be granted.

Plaintiffs assert that “[o]n its face, the ... policy violates the prohibition against general warrants[,]” and that the policy violates Article I, Section 20's guarantee against unreasonable searches conducted by the government.

We are inclined to agree that the policy violates the prohibition against general warrants. See In re Stumbo, 582 S.E.2d 255, 266 (2003) (Martin, J., concurring) (“[P]ermitting government actors ‘to search suspected places without evidence of the act committed’ ... is tantamount to issuing a general warrant expressly prohibited by the North Carolina Constitution.”). However, because we hold, for the reasons set forth below, that the Board's policy violates Article I, Section 20's guarantee against unreasonable searches, we do not reach the question of whether the policy violates the prohibition against general warrants.

The language of Article I, Section 20 “‘differs markedly from the language of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.’” Nevertheless, Article I, Section 20 provides protection “similar” to the protection provided by the Fourth Amendment, and it is well-settled that both Article I, Section 20 and the Fourth Amendment prohibit the government from conducting “unreasonable” searches.... [W]e first determine whether the policy violates the Fourth Amendment .... If we determine that the policy does not violate the Fourth Amendment, we may then proceed to determine whether Article I, Section 20 provides “‘basic rights in addition to those guaranteed by the [Fourth Amendment].’”

The reasonableness of a governmental search is generally determined “by balancing the nature of the intrusion on the individual's privacy against the promotion of legitimate governmental interests.” But “‘some quantum of individualized suspicion is usually a prerequisite to a constitutional search or seizure.’” The Fourth Amendment, however, “‘imposes no irreducible requirement of [individualized] suspicion.’” “‘[I]n certain limited circumstances, the Government's need to discover ... latent or hidden conditions, or to prevent their development, is sufficiently compelling to justify the intrusion on privacy entailed by conducting ... searches without any measure of individualized suspicion.’” Thus, a suspicionless search may be reasonable under the Fourth Amendment where “‘special needs, beyond the normal need for law enforcement, make the warrant and probable-cause requirement impracticable.’”

Where the government alleges “special needs” in justification of a suspicionless search, “courts must undertake a context-specific inquiry, examining closely the competing private and public interests advanced by the parties.” An important consideration in conducting the inquiry is whether there is “any indication of a concrete danger demanding departure from the Fourth Amendment's” usual requirement of individualized suspicion. The purpose of the inquiry is “to determine whether it is impractical to require a warrant or some level of individualized suspicion in the particular context.” Conducting the inquiry, the United States Supreme Court has upheld suspicionless searches in the following instances: (1) drug testing of students seeking to participate in competitive extracurricular activities; (2) searches of probationers; (3) drug testing of railroad employees involved in train accidents; (4) drug testing of United States customs officials seeking promotion to certain sensitive positions; and (5) searches of government employees' offices by the employer.

We begin our inquiry by attempting to examine the intrusiveness of the proposed testing procedure.... [Even] assuming the Board only tests employees' urine, we emphasize that the policy provides that “[a]ny employee who is found through drug or alcohol testing to have in his or her body a detectable amount of an illegal drug or of alcohol” will be suspended. Although a litany of other provisions in the policy bear directly on the intrusiveness of the testing procedure, we find it unnecessary to venture beyond this provision to state that the policy is remarkably intrusive.

We next consider whether Board employees have a reduced expectation of privacy by virtue of their employment in a public school system. Public employees may have reduced expectations of privacy if their employment carries with it safety concerns for which the employees are heavily regulated. By way of illustration, chemical weapons plant employees are heavily regulated for safety. There is no evidence in the record before us, however, that any of the Board's employees are regulated for safety. We question whether the Board could produce such evidence. The Board errantly relies on the premise that “Fourth Amendment rights ... are different in public schools than elsewhere; the ‘reasonableness' inquiry cannot disregard the schools' custodial and tutelary responsibility for children.” The Board, however, fails to account for the explicit teaching of the Supreme Court that because “the nature of [the schools' power over schoolchildren] is custodial and tutelary, [the schools' power] permit[s] a degree of supervision and control [over schoolchildren] that could not be exercised over free adults.” We are unable to conclude from this record that any of the Board's employees have a reduced expectation of privacy by virtue of their employment in a public school system.

Finally, the record in the case at bar is wholly devoid of any evidence that the Board's prior policy was in any way insufficient to satisfy the Board's stated needs. [The prior policy "required all job applicants to pass “an alcohol or drug test” as a condition of employment; required all employees to submit to “an alcohol or other drug test” upon a supervisor's “reasonable cause” to believe that the employee was using alcohol or illegal drugs, or abusing prescription drugs, in the workplace; and required “[a]ny employee placed on the approved list to drive school system vehicles” to submit to “random drug tests.” Additionally, the policy mandated the suspension of any employee who, in a supervisor's opinion, was impaired by alcohol or drugs in the workplace." -EV]

The Board acknowledges that there is no evidence in the record of any drug problem among its employees. There is also a complete want of evidence that any student or employee has ever been harmed because of the presence of “a detectable amount of an illegal drug or of alcohol” in an employee's body. We agree that the Board need not wait for a student or employee to be harmed before implementing a preventative policy. However, the evidence completely fails to establish the existence of a “concrete” problem which the policy is designed to prevent. The need to promote an anti-drug message is “symbolic, not ‘special,’ as that term draws meaning from [the decisions of the United States Supreme Court].”

Considering and balancing all the circumstances, we conclude that the employees' acknowledged privacy interests outweigh the Board's interest in conducting random, suspicionless testing. Accordingly, we hold that the policy violates Article I, Section 20's guarantee against unreasonable searches.

We reject the Board's assertion that “ample guidance to uphold the Board's drug testing policy” can be found in Boesche v. Raleigh-Durham Airport Authority, 432 S.E.2d 137 (N.C. Ct. App. 1993). The plaintiff in Boesche was an airport maintenance mechanic whose job duties generally consisted of “performing preventative maintenance and repairs on airport terminal [HVAC] systems, but plaintiff also had security clearance to drive a motor vehicle 10 M.P.H. in a designated area on the apron of the flight area in order to get access to the systems located on the outside of the building.” Without expressing that the plaintiff was suspected of any individualized wrongdoing, the defendants asked the plaintiff to submit to a urine drug test. The defendants told the plaintiff that the test was required “pursuant to a Federal Aviation Administration directive requiring that all employees who drive a motor vehicle in the airside of the airport must be tested.” The plaintiff refused to submit to the test, was fired, and subsequently [sued] .....

In stating that the Boesche plaintiff was in a position “in which public safety or the safety of others was an overriding concern,” this Court merely held that the defendants had made the showing ... that the plaintiff had “duties fraught with such risks of injury to others that even a momentary lapse of attention can have disastrous consequences.” This Court did not hold that any public employee who, “if drug impaired ..., could increase the risk of harm to others” was subject to urine drug testing. Rather, the Court held that the plaintiff, “if drug impaired while operating a motor vehicle on the apron of the flight area, could increase the risk of harm to others.” ...

In the case before us, there is absolutely no evidence in the record which in any way equates the safety concerns inherent in the driving of a motor vehicle on the apron of an airport's flight area with the safety concerns inherent in the job duties of any Board employee. In fact, there is absolutely no evidence in the record that any Board employee whose body contains “a detectable amount of an illegal drug or of alcohol” increases the risk of harm to anyone.

Ban on Divorced Father's "Exposing the Children to His Homosexual Partners and Friends":

A Georgia trial court imposed such a ban in 2007; the Georgia Supreme Court just set it aside on Monday, in Mongerson v. Mongerson:

There is no evidence in the record before us that any member of the excluded community has engaged in inappropriate conduct in the presence of the children or that the children would be adversely affected by exposure to any member of that community. The prohibition against contact with any gay or lesbian person acquainted with Husband assumes, without evidentiary support, that the children will suffer harm from any such contact. Such an arbitrary classification based on sexual orientation flies in the face of our public policy that encourages divorced parents to participate in the raising of their children, and constitutes an abuse of discretion. See Turman v. Boleman, 235 Ga. App. 243, 244 (1998) (abuse of discretion to refuse to permit mother to exercise visitation rights with child in the presence of any African-American male); In the Interest of R.E.W., 220 Ga. App. 861 (1996) (abuse of discretion to refuse father unsupervised visitation with child based on father’s purported “immoral conduct” without evidence the child was or would be exposed to undesirable conduct and had or would be adversely affected thereby). In the absence of evidence that exposure to any member of the gay and lesbian community acquainted with Husband will have an adverse effect on the best interests of the children, the trial court abused its discretion when it imposed such a restriction on Husband’s visitation rights.

Two justices (Melton and Carley) "write separately to emphasize" that the quoted passage above "should only be read to stand for the well-settled proposition that, absent evidence of harm to the best interests of the children through their exposure to certain individuals, a trial court abuses its discretion by prohibiting a parent from exercising their visitation rights while in the presence of such individuals (in this instance, Husband’s homosexual partners and friends)."

By the way, here's an extract from the 1998 Turman case, which I hadn't heard of it until now:

Turman and Boleman were divorced on November 13, 1996. Their settlement agreement, which was incorporated into the final judgment and decree, provided that Boleman would have custody of their minor child. The agreement gave Turman certain specified visitation rights away from the father's residence “on the condition [that] at no time shall [the child] be in the presence of William ‘Larry’ Little or any other African-American male except that [Turman] shall not be in contempt of court if she has casual contact with any African-American male other than William ‘Larry’ Little.” After Turman married Kenneth Turman, an African-American male, Boleman refused to allow Turman to visit with the child away from Boleman's residence. Turman moved to hold Boleman in contempt for refusing to allow her to exercise her visitation rights. At the hearing on the contempt motion, Turman argued that the provision in the settlement agreement conditioning her visitation rights upon the child's having no contact with any African-American male was unenforceable.

The trial court improperly upheld the validity of the visitation provision which prohibited the child's contact with any African-American males. This provision is unenforceable as against public policy.... The visitation provision here violated the express public policy against racial classification and the public policy encouraging a child's contact with his noncustodial parent.

The trial court held that the provision was enforceable because it was a matter of private contract. However, after that private agreement was incorporated into the trial court's order, enforcing the private agreement became state action.... The courts of this State cannot sanction such blatant racial prejudice, especially where it also interferes with the rights of a child in the parent/child relationship.

The agreement between the parties clearly violated the State's public policy to promote the best interests of the child. “It is the express policy of this state to encourage that a minor child has continuing contact with parents and grandparents who have shown the ability to act in the best interest of the child and to encourage parents to share in the rights and responsibilities of raising their children after such parents have separated or dissolved their marriage.” Contrary to this policy, the agreement prevents the child from having contact with his natural mother solely on the basis of an arbitrary racial classification. Although a court may validly provide, under appropriate circumstances, that a child is to have no contact with particular individuals who are deemed harmful to the child, such provision cannot be based solely upon racial considerations, as such ruling violates the public policy of the State of Georgia.

Monday's Mongerson, with which I began the post, apparently doesn't have this extra twist of an initial agreement by the parties; the father seemingly either never agreed to the "[no] exposing the children to ... homosexual partners and friends" condition, or agreed to it only because the trial court "express[ed] its opinion that, but for the agreement, the trial court would not have permitted Husband the limited contact to which the parties agreed" (and then promptly appealed the trial court order).

Thanks to How Appealing for the pointer.

Godfather and the Law:

From U.S. v. Kincannon (7th Cir.):

The government’s closing argument came next, during which the prosecutor made an analogy to an Academy-Award-winning movie: The Godfather. Recounting a pivotal scene where the director simultaneously presented assassinations orchestrated by the protagonist, Michael Corleone, the prosecutor explained that he, like the movie’s director, would attempt to seamlessly tell the “story of what happened” in this case....

Kincannon ... argues, for the first time on appeal, that the prosecutor inflamed the passions of the jury, rendering the trial unfair, by referring in closing argument to The Godfather ....

The prosecutor’s reference to The Godfather does not approach impropriety. It would be one thing if the government compared Kincannon to Michael Corleone, an organized crime kingpin responsible for murders and a whole host of other criminal activity. Such an analogy would be utterly unmoored from the record, which is probably why the government made no such connection. It was not Corleone’s criminality, but Francis Ford Coppola’s direction that was at the heart of the prosecutor’s closing remarks. The prosecutor alluded to the pivotal point in the movie where Corleone attends his godchild’s

christening. Coppola cuts to various scenes of assassinations orchestrated by Corleone as a priest dubbed him the child’s godfather. The poetic implication is that the murders,

like the priest’s liturgy, made Michael the godfather of the Corleone crime family. As the prosecutor said, “[n]ow that is how you present events that occur simultaneously

in a movie so the viewer can understand it very easily.” We agree, as did the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, who nominated Coppola for an Oscar for best director. [Footnote: In an upset along the lines 2 of the 2009 Kentucky Derby win by Mine That Bird, the 1972 Oscar went to Bob Fosse (for Cabaret) rather than Coppola.] The prosecutor explained to the jury that he would try to do orally what Coppola did in his film — that is, tie together the events that occurred during the two controlled buys into one seamless story. To do so as eloquently as Coppola is a tall task, but there is certainly nothing improper about the attempt.

An interesting fact about the case, from the start of the opinion, "At 77 years old, James Kincannon makes for an unlikely methamphetamine dealer. But looks can be deceiving." And from later on, "Kincannon was in his fifties when his criminal record started and days away from his 73rd birthday when he was last released from prison after being popped for distributing drugs."

Plural and Singular Forms of "You":

In modern English, second-person pronouns have the same form in the singular and the plural -- "you," for instance, can mean either one person or a group. (I set aside the now almost entirely archaic "thou," and the regional "y'all.") The same is true in some other languages, at least as to the formal second-person singular. (The informal second-person singular, equivalent to the archaic English "thou," survives in at least some of those languages.)

But what second-person pronoun form is actually different in the singular and in the plural? It might be obvious to most of you, but I just thought about it a few days ago, when talking to my 5-year-old, and realized that I'd never consciously noticed the difference before (though I'm pretty sure I always use both forms correctly).

A Flaw in George Soros' Case for Increased Government Regulation of the Financial System:

I am no expert on finance. Therefore, I cannot tell whether George Soros' proposals for increased regulation of the financial system have merit or not. Soros has probably forgotten more about finance than I ever knew to begin with. However, Soros' position has at least one serious weakness that is common to many arguments for increased government intervention in society: it fails to give adequate consideration to the shortcomings of the political process. Strangely, Soros admits that government is likely to do an even worse job in this area than he believes the private sector has; yet he still ends up supporting increased regulation.

Soros argues that speculative bubbles are a form of market failure that can cause great harm to the economy when the bubbles pop. He therefore concludes that we need government intervention to prevent bubbles from forming. However, he concedes that government regulators are unlikely to do any better at predicting dangerous bubbles than the market does:

[S]ince markets are bubble-prone, regulators must accept responsibility for preventing bubbles from growing too big. Alan Greenspan, the former chairman of the Federal Reserve, and others have expressly refused that responsibility. If markets cannot recognise bubbles, they argued, neither can regulators. They were right and yet the authorities must accept the assignment, even knowing that they are bound to be wrong. They will, however, have the benefit of feedback from the markets so they can and must continually re-calibrate to correct their mistakes. [Emphasis added]

If, as Soros believes, government regulators will be just as bad or worse at predicting bubbles than market participants, it's not clear why he expects government intervention in this area to improve things. "Feedback from markets" certainly doesn't create any comparative advantage for government regulators; after all, the private sector can use feedback from markets as well.