|

Volume-mates with Orin:

Orin recently announced that his article on Four Models of Fourth Amendment Protection is forthcoming in the Stanford Law Review.

I'm delighted to report that I, too, have accepted a publication offer with Stanford — in my case, for my article on Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy. (The link in the previous sentence will take you to the very latest version on SSRN — exactly 25,000 words!) Here, again (for those of you who didn't pay attention when I've posted this before), is the abstract:

A common argument against privatization is that private providers will self-interestedly lobby to increase the size of their market. In this Article, I evaluate this argument, using, as a case study, the argument against prison privatization based on the possibility that the private prison industry will distort the criminal law by advocating for incarceration.

I conclude that there is at present no particular reason to credit this argument. Even without privatization, government agents already lobby for changes in substantive law — in the prison context, for example, public corrections officer unions are active advocates of pro-incarceration policy. Against this background, adding the “extra voice” of the private sector will not necessarily increase either the amount of industry-increasing advocacy or its effectiveness. In fact, privatization may well reduce the industry’s political power: Because advocacy is a “public good” for the industry, as the number of independent actors increases, the dominant actor’s advocacy decreases (since it no longer captures the full benefit of its advocacy) and the other actors free-ride off the dominant actor’s contribution. Under some plausible assumptions, therefore, privatization may actually decrease advocacy, and under different plausible assumptions, the net effect of privatization on advocacy is ambiguous.

The argument that privatization distorts policy by encouraging lobbying is thus unconvincing without a fuller explanation of the mechanics of advocacy.

Those of you who want a technical, economicsy, paper on the topic can check out this one. In the near future, I'll have a series of posts summarizing the argument of this paper.

Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy:

As I noted in a recent post, I'm delighted to be publishing my article, Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy, with the Stanford Law Review. (Those of you who want to read something more technical can check out my economics paper on the subject, Privatization, Free-Riding, and Industry-Expanding Lobbying.) This will be the first of a series of blog posts summarizing the paper. Comments are welcome, as the paper won't be published until next year.

* * *

Over 90 years ago, opponents of World War I alleged that “munitions manufacturers frighten the popular mind with the fear of imaginary external enemies and inflame it with murderous patriotism.” According to Stefan Zweig, the war began only when “newspapers in the pay of the arms manufacturers began to whip up sentiment against Serbia.” After the war, that accusation morphed into the charge that arms makers were self-interestedly obstructing peace efforts. Today, an opponent of U.S. military policy characterizes defense contractor CACI International Inc, whose chairman speaks publicly of the “heinous[ness],” “fanatical horror,” and “barbarism” of terrorism, as “one of the most unabashed corporate backers of Bush’s foreign policy and a key supporter of the military campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan.” Critics also charge that private military interests affect what weapons systems we rely on and what alliances we enter into, and that, in some countries, those interests may even take over the government.

This theme—that private contractors use their influence to advocate not just privatization but also, insidiously, changes in substantive policy—sweeps more broadly than just defense contractors. The following list gives a sense of the generality of the accusation; the last few items illustrate that the critique comes from “the right” as well as from “the left.”

- Private prison firms are often accused of lobbying for incarceration because, like a hotel, they have “a strong economic incentive to book every available room and encourage every guest to stay as long as possible.”

- Business improvement districts—coalitions of business and property owners, many of which have their own private security forces—have lobbied municipalities for, among other things, aggressive panhandling ordinances.

- A toll road developer in Colorado has lobbied for statutory changes to preempt county authority to set toll rates, and a private road construction firm has been accused of contributing to Texas Supreme Court justices’ campaign chests to influence a potential eminent domain suit related to a toll road in the state.

- Private landfill companies have been accused of “shap[ing] landfill laws” to keep them “weak” so they can “compete with and undercut valuable recycling programs.”

- Private water supply owners have been accused of “lobbying to weaken water quality standards[] and pushing for trade agreements that hand over the U.S. water resources to foreign corporations,” and private water utilities have been accused of fighting conservation efforts.

- Private redevelopment corporations, which have the power to condemn private property for purposes of “urban renewal,” have opposed reform of eminent domain laws in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in Kelo v. New London.

- And “private attorneys general,” for instance environmental groups that benefit from fines available under environmental citizen suit provisions, or members of the securities plaintiffs’ bar who benefit from the availability of securities fraud class actions, fight for the continued vitality or even strengthening of the statutes under which they litigate.

In this Article, I examine this “political influence” challenge to privatization using the case study of private prisons. I conclude that, in the prison context, there is at present no reason to credit the argument. At worst, the political influence argument is exactly backwards, by which I mean that privatization will in fact decrease prison providers’ pro-incarceration influence; at best, the argument is dubious, by which I mean that whether it is true or false depends on facts that proponents of the argument have not developed.

Private prisons are a useful case study. First, they are a growth industry, having progressed from humble beginnings in the late ’70s and early ’80s to now house about one in sixteen prison inmates nationwide. Second, the opponents of private prisons commonly make the political influence argument.

For example, in a recent Duke Law Journal article, Sharon Dolovich writes that “the legitimacy of punishment” is threatened “whenever parties with a financial interest in increased incarceration are in a position to exert influence over the nature and extent of criminal sentencing. If this concern is real”—and she suggests that it may well be—prisons should not be privatized because “the state ought not to foster yet another potentially influential industry that could seek to compromise further the possibility of legitimate punishment to promote that industry’s own financial interests.”

David Shichor, a prominent contributor to the prison privatization literature, opposes prison privatization in part because:

Through political lobbying, PACs, campaign contributions, and the provision of perks to politicians (as industrial and business corporations do), corporations are likely to continue to support and even accelerate incapacitation-oriented legislation and policies by which more people will spend longer periods of time in correctional institutions. Conversely, this trend may diminish the emphasis on alternative programs and will result in the pursuance of the “Hilton Inn mentality,” that is, trying to maintain high occupancy rates for profit purposes.

And Brigette Sarabi and Edwin Bender’s thesis is clear from the title of their report, The Prison Payoff: The Role of Politics and Private Prisons in the Incarceration Boom, in which they argue that prison privatization should be resisted in part because private prison firms have a “vested financial interest[] in increasing rates of imprisonment.” This is only a small sample of the literature. Click here (mw112) for a sample of the art.

* * *

This is just some set-up for the question. In later posts, I'll discuss my actual thesis, lay out my economic model, and discuss evidence.

Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy, Part 2:

In my previous post, I introduced my forthcoming Stanford Law Review article, Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy. (Again, for those who are interested in a more technical exposition, you can also check out my related economics paper.) I explained the nature of the political-influence argument against privatization, and quoted from recent writers who have applied this critique to prison privatization. This post gives a brief outline of my argument, which I will develop further in later posts.

* * *

I assume, for purposes of this Article, that the concern underlying this critique is reasonable—that is, that economically self-interested pro-incarceration advocacy is undesirable. (Though in fact, this is not at all clear; I'll return to this point later.) This concern, however, fails to support the argument against privatization for several reasons.

First, the public sector—chiefly public corrections officers’ unions—is already a major self-interested pro-incarceration political force. For instance, the most active corrections officers’ union, the California Correctional Peace Officers Association, has contributed massively in support of tough-on-crime positions on voter initiatives and has given money to crime victims’ groups, and public corrections officers’ unions in other states have endorsed candidates for their tough-on-crime positions. Private firms would thus enter, and partly displace some of the actors in, a heavily populated field.

Second, there is little reason to believe that increasing privatization would increase the amount of self-interested pro-incarceration advocacy. In fact, it is even possible that increasing privatization would reduce such advocacy. The intuition for this perhaps surprising result comes from the economic theory of public goods and collective action.

The political benefits that flow from prison providers’ pro-incarceration advocacy are what economists call a “public good,” because any prison provider’s advocacy, to the extent it is effective, helps every other prison provider. (We call it a public good even if it is bad for the public: The relevant “public” here is the universe of prison providers.) When individual actors capture less of the benefit of their expenditures on a public good, they spend less on that good; and the “smaller” actors, who benefit the least from the public good, free-ride off the expenditures of the “largest” actor.

In today’s world, the largest actor—that is, the actor that profits the most from the system—tends to be the public-sector union, which still provides the lion’s share of prison services and whose members benefit from wages significantly higher than those of their private-sector counterparts; the smaller actor is the private prison industry, which not only has a small proportion of the industry but also does not make particularly high profits.

By breaking up the government’s monopoly of prison provision and awarding part of the industry to private firms, therefore, privatization can reduce the industry’s advocacy by introducing a collective action problem. The public-sector unions will spend less because under privatization they experience less of the benefit of their advocacy, while the private firms will tend to free-ride off the public sector’s advocacy. This collective action problem is fortunate for the critics of pro-incarceration advocacy—a happy, usually unintended side effect of privatization. One might even say that prison providers under privatization are led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of their intention.

This is the simplest form of the story, but one can also tell more complicated versions of the story in which privatization doesn’t necessarily decrease industry-expanding political advocacy. After presenting my main model, I introduce a few realistic complications into the model to show how the effect of privatization could be ambiguous—increasing private-sector advocacy but also decreasing public-sector advocacy. If those extensions of the model are closer to the truth, then total advocacy may rise—but it may also fall, depending on which effect dominates. We cannot determine the net effect a priori.

There is thus no reason to believe an argument against prison privatization based on the possibility of self-interested pro-incarceration advocacy—unless the argument takes a position on how lobbying, political contributions, and advocacy work, and why (for instance) increases in private-sector advocacy would outweigh the decrease in public-sector advocacy. Either this argument against prison privatization is clearly false, or it is only true under certain conditions that the critics of privatization have not shown exist.

The analysis here not only sheds light on the prison privatization debate but also provides a roadmap for analyzing military contracting and other privatization contexts. Because privatization can affect the incentives of both the private and public sectors to wield political influence, one shouldn’t conclude that privatization distorts substantive policy unless one can tell a story, based on a plausible view of government agents’ behavior, in which private-sector advocacy rises more than public-sector advocacy falls. In the end, each industry has its own idiosyncrasies, so I do not make a strong claim about the use of the argument outside of prisons. But, at the very least, the use of the political influence argument is often theoretically unsound to the extent it ignores this comparative analysis.

* * *

In later posts, I'll set forth my main model. In this model, the sector with the greatest benefit from the expansion of the industry does all the advocacy, and the sector with the smaller benefit free-rides off the larger one. Thus, privatization will reduce industry-expanding advocacy if, after privatization, the public sector remains the sector with the greatest benefit.

Then, I'll apply the theoretical model to prisons and suggest, based on an informal calculation, that the actors that would benefit the most from increased incarceration are indeed the public-sector corrections officers’ unions. Thus, we should expect the public sector to do all the pro-incarceration lobbying (though less than it would have done without privatization). This simple model, despite its stark result, may be quite close to the truth, as there is a wealth of evidence that public corrections officers’ unions advocate incarceration, and no such hard evidence on the private side.

I'll explain why it is appropriate to focus on public corrections officers’ unions and private prison firms as the relevant actors, and how cooperation within the prison industry affects the results. Finally, I'll complicates the model in various ways. Some of these complications don’t change the basic result of the simple model. Other complications make the result muddier, so that instead of unambiguously reducing advocacy, privatization has a theoretically ambiguous effect on the amount of industry-expanding advocacy.

Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy, Part 3 -- The Model:

This post continues my series on my upcoming Stanford Law Review paper on Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy (see here for the technical paper). This installment is not connected to privatization specifically at all, much less prisons, but gives (in plain English) the basic economic theory behind public goods and free riding.

* * *

I now present the main model I use to predict how industry actors will react to privatization. The central feature of the model is that industry-increasing advocacy is a public good. Privatizing part of the industry therefore introduces a collective action problem: Unless everyone in the industry cooperates with each other, they will together spend less on industry-increasing advocacy than a single firm would if it covered the whole industry, because a portion of their expenditures will benefit their competitors.

This intuition should not be surprising, as it is standard in the literature on public goods. When a good is private, everyone pays for, and enjoys, only his own consumption. By contrast, when a good is public, in the classic model, everyone benefits from the total amount, and this amount is determined by the total amount of contribution.

If we benefit from our national defense, we benefit from the full amount, not from the chunk we paid for; we cannot be excluded from the full benefit, no matter how little we paid; and the total amount of national defense is just determined by how much money Congress allocated to national defense from the Treasury. A tax-funded program that improves air quality benefits everyone who breathes the relevant air, whether or not they contributed to the program; and the total improvement is just determined by the amount of resources directed toward that goal.

Similarly, contributing to a candidate’s campaign benefits all of his supporters; and it is not too implausible to say, as an approximation, that to the extent the money he raises and spends affects his probability of winning, it is only the total amount of money that matters.

In all these cases, the temptation to free ride off one’s fellows’ contributions is strong—so strong that the category of “public goods” is standard among economists as a case of “market failure.”

To explore the basic model, consider a monopolist, who's willing to invest some amount of money in lobbying to increase the size of his industry. To determine that amount, he weighs the benefit that his money can buy—the expansion of the industry is worth something to him, and money can help his policy pass—against the cost of the lobbying.

If that firm is broken up into two smaller firms—say a 90% incumbent firm and a 10% splinter firm—the larger incumbent isn’t willing to spend as much as it used to be, because the costs of lobbying are the same while the benefits are 10% less than they used to be. And the smaller splinter firm won’t be willing to spend anything, because it will be satisfied free-riding off the larger incumbent’s lobbying. Thus, splitting up an industry tends to decrease industry-expanding lobbying.

The rest of this post will illustrate this intuition graphically.

Suppose you are, as economists say, a rational, risk-neutral expected utility maximizer. One may dispute how much of life this assumption can explain, but on balance it seems to be at least a good starting point for predicting the behavior of business organizations. You are faced with the choice of whether or not to spend a dollar on political advocacy—donating to the campaign of a politician or voter initiative, contributing to your trade association’s lobbying expenses, or running an ad—in favor of some reform that could increase the size of your market. We may assume that this dollar has some influence in the world, whether appropriate or inappropriate—it could corrupt a legislator, raise the chance of his election, contribute to the passage of the initiative, or change popular opinion.

The benefit of this dollar is the value of the increased probability of getting your desired policy change. It is reasonable to think that spending money on advocacy is subject to decreasing marginal returns, so each additional dollar gets you less and less benefit. The cost of a dollar, on the other hand, is and remains $1, no matter how many of them you spend. As long as the benefit of an advocacy dollar is greater than $1, you continue spending; and you stop as soon as that benefit reaches $1. Finally, you settle on the optimal total amount of advocacy spending—say $1 million.

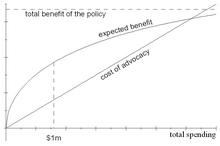

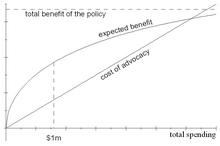

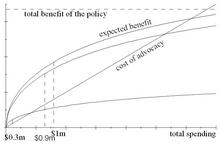

The picture below illustrates the situation. The expected benefit—that is, the probability of success times the benefit—is represented by the curved line below: The more you spend, the greater the probability of success, but the less you get for each extra dollar; and because a probability can’t get any higher than 1, the curve is bounded above by the dashed line representing the total benefit of the policy. The cost of advocacy is represented by the straight line below: Each dollar of advocacy costs $1. Your problem is to maximize the vertical distance between the expected benefit curve and the cost line. In the figure, that maximum distance occurs at a spending level of $1 million.

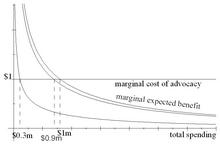

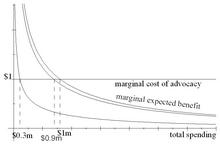

The next picture is an equivalent way of seeing the same problem. The curve below represents the marginal expected benefit—that is, the benefit of an extra dollar of spending, which is just equal to the total benefit times the extra probability that a dollar buys you. As noted above, the marginal benefit is decreasing. The straight line is the marginal cost of advocacy: An extra dollar of advocacy always costs $1. If the marginal expected benefit is above $1, you’re not spending enough; if it’s below $1, you should cut back. At a spending level of $1 million, an additional dollar of spending gives you exactly $1 of expected benefit.

Now suppose the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division comes in and splits you up, so that you now have 90% of the market and are faced with a competitor with the other 10%. Your previous optimal amount, $1 million, is no longer optimal for you: The cost of that last dollar was $1, and while the benefit of the dollar is $1 for the whole industry, you, who now represent only 90% of the industry, only see 90¢ of that benefit. All your benefits are now lower by 10% because you have to share them with your competitor; for our purposes, the split-up thus has the same effect as a 10% tax on your benefit.

Because your spending on advocacy—an investment in the growth of your industry—is only 90% as productive, you do less of it. You start cutting back on your spending, because a dollar saved puts $1 back in your pocket and only reduces your benefits by 90¢. As you cut back more, the benefit of the last dollar rises; you stop cutting back as soon as the benefit of your last dollar to the industry reaches about $1.11 (which is a $1 benefit to you). Call the new amount $900,000.

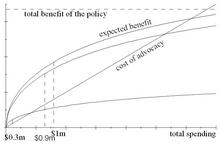

This new situation is illustrated in the next pictures. In the next one, the top curve is the expected benefit to the whole industry (as before), and the second curve is your expected benefit, newly reduced now that you only have 90% of the industry. The bottom curve is your 10% competitor’s expected benefit. The maximum vertical distance between your curve and the cost line now occurs at $900,000, and the maximum distance between your competitor’s curve and the cost line occurs at $300,000.

In the next picture, the equivalent graph that shows marginal quantities instead of total quantities, you want to find the point where the marginal expected benefit to the industry is $1.11. This is equivalent to finding the point where 90% of the marginal expected benefit (i.e., the benefit to you) is $1. That point is again $900,000. And your competitor wants to find the point where the marginal expected benefit to the industry is $10, which gives him $1; this is again $300,000.

This story is incomplete. You don’t want the amount spent to be exactly $900,000; obviously, you would be thrilled if other people happened to contribute more. It’s just that you’re not personally willing to put any dollar into the pot after the 900,000th. You want the total amount spent to be at least $900,000, and are willing to contribute money until that point is reached, but you stop being willing to personally contribute once you’re holding the 900,001st dollar.

This is because, in this model, the benefit of a dollar only depends on the total amount of money spent, and if the 900,000th dollar had a benefit to the industry worth $1.11 (and thus a benefit to you worth $1), then the 900,001st dollar has a benefit worth slightly less than $1.11.

Your new competitor, who represents the remaining 10% of the industry, and who is equally interested in this reform that will increase the size of the pie, wants the total amount spent to be at least $300,000, and won’t put a 300,001st dollar into the pot.

All this leads to two conclusions.

First, the total amount spent should not exceed $900,000. If it did, you would want to take some money out of the pot, since the dollars beyond the 900,000th are giving the industry a benefit below $1.11, and therefore giving you a benefit below $1.

Second, there’s no reason for your competitor to spend anything. He’s unwilling to spend any dollar beyond the 300,000th, since its marginal benefit to the industry is under $10, and so its marginal benefit to him is under $1. Thus, suppose you were going to spend $600,000 and he was going to spend $300,000. These actions would not be an equilibrium, since he would prefer to keep his $300,000. Why should he spend any extra dollar beyond the $600,000 you’re already spending, if the 300,001st dollar already isn’t worthwhile to him? The only equilibrium is where you give $900,000 and he gives $0. Because he’s the smaller actor, he totally freerides off you. The result is what Mancur Olson calls the “systematic tendency for ‘exploitation’ of the great by the small.”

Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy, Part 4 -- Miscellaneous Points on the Model:

This post continues my series on my upcoming Stanford Law Review paper on Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy (see here for the technical paper). The last post set out the basic economic model -- read that post, if you haven't already and if you want to understand this post. This post just elaborates a bit on the basic model -- and applies it to prisons -- before we go on to apply the model to the real world and prisons.

* * *

If one accepts the fundamental assumption of this Part—that the probability of success only depends on the total amount of money in the pot—this simple model is flexible enough to accommodate many institutional details of privatization. The total free-riding result happens whenever one sector has a lower threshold than the other, for whatever reason. In this story, you and your competitor are identical except that you have 90% of the industry and he has 10%. But one’s threshold could be lower for other reasons as well.

For instance, suppose that, to add insult to injury, the government not only breaks you up but also subjects your revenues to a high (50%) tax rate. The breakup already altered your spending threshold by making all your curves shift down to 90% of their previous level (see the figures in the previous post). Now, with the 50% tax, your revenue and marginal revenue curves shift further down—to 45% of their original levels. (If your 10% competitor is subject to the same tax, his curves are 5% of the original industry curves.)

So the combination of the breakup and the tax makes you act like a 45% firm. These new percentages—call them “real” shares—no longer need to add up to 100% (in fact, with the 50% tax, they add up to 50%), but they convey the economic intuition that your spending threshold is lower when, for whatever reason, your benefits decrease.

After we determine everyone’s “real” shares, the same analysis applies as before: The “biggest” firm does all the advocacy, and the “smaller” firm free rides. The only difference is that we learn who is “biggest” not just by looking at proportions of the market but at shares of total industry revenue. Instead of calling this firm “biggest,” we’ll call it the “dominant” firm. Thus, if the tax rate on your revenues is 90%, you will act as though your share is 9%; and if your 10% competitor is exempt from the tax, then he, with his 10% share, is actually the dominant actor. Now you will free-ride off him.

In short, anything that affects your revenues affects your “real” share. Suppose, for instance, that your competitor is less profitable than you are: Your 90% share is a monopoly share in a 90% geographic area, while the remaining 10% is divided among 100 competitors who act according to the textbook perfect competition model, where everyone makes zero economic profits. Then those competitors—and thus that entire 10% sector—act as though they had a 0% share.

Or, as a final example, suppose that your competitor is better at advocacy. Perhaps, for whatever reason (maybe he is a slicker lobbyist), each dollar of his is twice as persuasive as a dollar of yours. Then, he acts as though his share is 20%, and his threshold goes up accordingly. All these considerations affect your “real” shares for purposes of choosing how much to spend on advocacy. (In this example, he still won’t do anything because 20% is still less than your 90% share.)

This model applies straightforwardly to privatization, which splits up an industry between public and private much as the Antitrust Division could split up a monopolistic firm. To be sure, the public sector is not a “profit maximizer” like a private firm. But the concept of profit maximization needn’t be interpreted in a narrow financial sense. Government agencies—or, more precisely, people who work at the agencies and who have some control over what the agencies do—pursue goals of some sort. Whether it is the Pentagon or a state Department of Corrections, a government agency does obtain some benefit from its service provision.

Moreover, agencies are not the only actors; the employees of the agencies, through their unions, also enjoy some benefit from public provision of the service, and they can also participate in political advocacy. The challenge is to determine who the relevant actors are and what benefits they might plausibly seek to maximize. This is what I will try to do in later posts for corrections agencies and corrections officers’ unions.

The model implies, at a minimum, that some amount of privatization will decrease advocacy, for two reasons. The first reason is that, as long as the level of privatization does not exceed a certain critical threshold, the public sector will dominate (in terms of “real” share) the whole private sector combined, so the model predicts that whole private sector’s advocacy would be zero. The second reason is that as privatization increases, the benefits of service provision to the public sector fall; because the public sector is smaller than it would be without privatization, its advocacy falls.

How far can we continue to privatize before advocacy stops falling? As privatization increases, the second step always holds—by definition, privatization shrinks the size of the public sector. The first step, however, does not always hold for large enough levels of privatization. Obviously, at a certain point, the private sector can come to dominate the public sector. Then the private sector will do all the advocacy, with the public sector free-riding, and from then on privatization might increase advocacy. The level of privatization at which advocacy stops falling is a threshold that we may call an “advocacy-minimizing privatization level.”

For instance—going back to the graphical model above—suppose our two firms benefit identically from having a given proportion of the industry. Then the advocacy-minimizing breakup is a 50–50 split (or 33–33–33 if the breakup is into three firms, and so on)—because under such a split, the dominant firm is as small as it can possibly get.

If a split creates a splinter firm that is twice as profitable as the incumbent firm, or perhaps twice as slick, then the advocacy-minimizing split is 67–33, again equalizing the firms’ stake in the system. The splinter firm is half as large but twice as profitable, so again the dominant firm (in terms of “real” share) is as small as it can possibly get. Conversely, if the splinter firm is only half as profitable as the incumbent firm, the advocacy-minimizing split is 33–67.

This concept becomes useful in later posts. I will argue that for prisons, the public-sector share of total benefit is much larger than the private-sector share—first, because the public sector still has a larger industry share, and second, because private firms are subject to a more competitive regime, so their profits are fairly low. Thus, the advocacy-minimizing level of privatization is probably quite high. Within this model, it would take a lot more privatization before pro-incarceration advocacy stops falling.

This basic result—that, by fragmenting an industry, one can reduce that industry’s political advocacy to increase its market—is also consistent with empirical studies on the relationship between industry concentration and lobbying.

In general, industry concentration can have two opposing effects on lobbying. The first effect is the one discussed above: A concentrated industry can more easily overcome its collective action problems, so we should expect it to lobby more. But not all lobbying is industry-expanding; some lobbying is simply anti-competitive, seeking to regulate the market (for instance, through entry restrictions) to allow existing firms to charge above-market prices. Firms in a more concentrated industry can more easily cooperate to suppress competition in the product market, so they have less need for anti-competitive lobbying: They can raise prices above market levels all by themselves by directly using anti-competitive methods.

Thus, studies that don’t disentangle these effects can come up with results in either direction. One study found a positive effect of concentration on industry contributions, while another found that the percentage of firms in an industry that had political action committees rises and then falls as concentration goes up.

Here, though, I focus only on advocacy for reforms that increase the size of the industry, and not on advocacy for reforms that would squelch competition in the industry—since it is primarily the first sort of advocacy that privatization critics urge is illegitimate. So only the first of these forces comes into play here.

Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy, Part 5:

This post continues my series on my upcoming Stanford Law Review paper on Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy (see here for the technical paper). Two posts ago, I set out the basic economic theory—be sure to read that post if you're having trouble following (or if you're disagreeing with) the discussion of free-riding. And in the last post, I discussed various miscellaneous points about the theory and how it applies to privatization. Now, on to the primary case study in the paper: prisons.

* * *

Now let us apply the theory to a real-world industry subject to the “political influence” critique of privatization: prisons. When I speak of “pro-incarceration advocacy,” I use the term “advocacy” broadly to include any use of political influence, licit or illicit, including endorsements, political contributions, lobbying, and bribes. And I use the term “incarceration” as a shorthand to include the criminalization of a greater range of behavior, more active enforcement, greater reliance on imprisonment, longer sentences, and less parole; thus, endorsing a politician for being “tough on crime,” donating money to a “Three Strikes” initiative, or testifying in favor of a “truth in sentencing” law all count as advocating incarceration.

Consider the main political actors in the prison industry: the private prison firms and the public corrections officers’ union. Without privatization, the public sector is the monopoly provider of prison services, and the corrections officers’ union enjoys the benefits that flow from serving the whole system. Now suppose that part of the system is privatized. At first, the public sector is clearly the dominant sector, that is, the sector with the largest proportion of total benefits from provision of the service—from 100% of the industry, it has gone down slightly, and the private sector is not big enough to even come close. Because it has shrunk, it is less willing than it used to be to spend money on reforms that would increase the size of the prison pie. And because the private sector is tiny, it free-rides.

Provided the public sector stays the dominant sector, privatization will always have this effect—because, in terms of the model presented above, any reform that shrinks the dominant sector will reduce industry-expanding advocacy. As it happens, this proviso is true in the case of prisons. At current levels of privatization, the public sector both has a larger industry share and extracts more benefit from the system than does the private sector.

We can easily perform some rough estimates to verify this (I provide the detailed derivations of the numbers elsewhere):

Industry share. The private sector has a smaller share of the industry. Of the 1.5 million prisoners under the jurisdiction of federal or state adult correctional authorities in 2004, 7% were held in private facilities; this includes 14% of federal prisoners and 6% of state prisoners. Among the 34 states with at least some privatization, the median private percentage was 8–9%. If we are interested in the private share of marginal prisoners—i.e., how likely a prisoner is to go to a private prison if he is convicted today—the private share becomes larger, mainly because private firms have absorbed much of the recent growth in federal incarceration. A reasonable estimate of the private share of marginal prisoners over the period 2000–2005 yields 6% for state systems, 54% for the federal system, and 22% overall. Private-sector profitability. The profits of the private sector are low. If the industry were perfectly competitive—like in textbook models of perfect competition—every firm would make zero economic profit. “Economic profits” measures how profitable a company is relative to other ways of investing one’s money; thus, “zero economic profits” means not that firms are making no money but rather that all firms are doing as well as the rest of the market. In such a (hypothetical!) world, firms wouldn’t care whether their market were growing or shrinking, because they would be indifferent between running prisons and putting their money into the stock market. This is, of course, unrealistic—the prison industry is oligopolistic, so prison firms do make some profit. But not much: 10% would be a generous estimate of prison firms’ profitability. Public-sector rents. Public-sector correctional officers, on the other hand, benefit substantially from public provision of prisons, because their wages are quite a bit above what they would be making in the private sector—by about 30–65%. This is a lot of money, because wages are about 60–80% of most prisons’ operating expenses.

I make the assumptions—oversimplified but common in the economic literature on firms and unions—that firms maximize profits and that unions maximize total “union rents” (that is, the difference between public-sector and private-sector wages, times the size of the public sector). Trying to put these numbers together rigorously requires a fair amount of algebra, which I provide elsewhere. But it should be intuitively clear that the public sector extracts substantially more benefit from any given prison than does the private sector; and it is likewise clear that the public sector has a greater share of the industry than the private sector.

Thus, the public sector enjoys a greater benefit from prison provision than the private sector does, perhaps by an order of magnitude. This model predicts that the public sector should be doing all the pro-incarceration advocacy, and the private sector should be entirely free-riding. Moreover, privatization reduces the public sector’s share of total benefits. So, at current levels, privatization should cause total pro-incarceration advocacy to decrease.

Now, I know what you're thinking: Look, Volokh, you economists spin out your simple, highly stylized models, but can you really expect the private sector to do zero advocacy?

Whatever the general merits of such skepticism, in this case the simple model might actually be true.

The next post or two will document what we know about prison industry advocacy. In brief, there is a lot of hard evidence of pro-incarceration advocacy by public corrections officers’ unions (though a small part of union advocacy also cuts the other way). (There is also hard evidence that most Departments of Corrections advocate the other way—in favor of alternatives to incarceration.) But there is virtually no hard evidence of private-sector pro-incarceration advocacy. This may simply mean that the private sector advocates secretly. But, in light of the theory, it is more plausible that the private sector simply free-rides, saving its political advocacy for policy areas where the public good aspect is less severe—pro-privatization advocacy.

Even if one disagrees with the preceding sentence, this model needn’t be realistic in a literal sense. Advocacy needn’t be an entirely public good, and the actors in the industry needn’t totally free-ride. The point is merely that these assumptions are plausible, perhaps even likely. Advocacy has some public-good aspects, and free riding happens to some extent in the world. If people act enough like this model, privatization will still reduce total pro-incarceration advocacy.

This plausible scenario rebuts to the simple anti-privatization claim that privatization does increase pro-incarceration advocacy. (The extended models presented in even later posts, in which the effect of privatization on advocacy is ambiguous, further rebut the claim.) This scenario also points up a potential irony in the position of some incarceration opponents who, so as to avoid “reinforc[ing] the incarceration boom by introducing the profit motive into incarceration,” would make common cause with public corrections officers’ unions, who concededly are active lobbyists for incarceration.

Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy, Part 6:

This post continues my series on my upcoming Stanford Law Review paper on Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy (see here for the technical paper). In my last post, I wrote:

In brief, there is a lot of hard evidence of pro-incarceration advocacy by public corrections officers’ unions (though a small part of union advocacy also cuts the other way). (There is also hard evidence that most Departments of Corrections advocate the other way—in favor of alternatives to incarceration.) But there is virtually no hard evidence of private-sector pro-incarceration advocacy. This may simply mean that the private sector advocates secretly. But, in light of the theory, it is more plausible that the private sector simply free-rides, saving its political advocacy for policy areas where the public good aspect is less severe—pro-privatization advocacy.

This post documents that assertion. For a more footnoted version—there's a limit to how much I can link to here—consult the paper.

* * *

In 1987, E.S. Savas, a supporter of privatization, dismissed the claim that private firms advocate incarceration by noting that “[i]f this argument was sound . . . prison officials, guards, and their unions presumably would act in the same manner for the same reasons. This, however, is not the case.”

Whether this was true even back then is questionable. At one time, corrections officials were politically aligned with liberal groups, but by the 1970s correctional unions were already advocating incarceration.

This activism continues today. The most active public corrections officers’ union in advocating incarceration is the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA). It gives twice as much in political contributions as the California Teachers Association, though it’s only one-tenth the size; only the California Medical Association gives more in the state. CCPOA spends over $7.5 million per year on political activities. It contributes to political parties, political events, and debates; it gives money directly to candidates; it hires lobbyists, public relations firms, and polling groups.

Many of its contributions are impossible to trace back to any particular agenda item: Since the union also opposes privatization, favors higher wages, and has positions on other issues, it’s just as plausible that the contributions were made for those other purposes.

But many of its contributions are directly pro-incarceration. It gave over $100,000 to California’s Three Strikes initiative, Proposition 184 in 1994, making it the second-largest contributor. It gave at least $75,000 to the opponents of Proposition 36, the 2000 initiative that replaced incarceration with substance abuse treatment for certain nonviolent offenders. From 1998 to 2000 it gave over $120,000 to crime victims’ groups, who present a more sympathetic face to the public in their pro-incarceration advocacy. It spent over $1 million to help defeat Proposition 66, the 2004 initiative that would have limited the crimes that triggered a life sentence under the Three Strikes law. And in 2005, it killed Gov. Schwarzenegger’s plan to “reduce the prison population by as much as 20,000, mainly through a program that diverted parole violators into rehabilitation efforts: drug programs, halfway houses and home detention.”

CCPOA doesn’t always favor increasing incarceration, but the bulk of its advocacy has been in this direction. Dan Pens has quoted CCPOA member Lt. Kevin Peters as saying:

You can get a job anywhere. This is a career. And with the upward mobility and rapid expansion of the department, there are opportunities for the people who are [already] correction staff, and opportunities for the general public to become correctional officers. We’ve gone from 12 institutions to 28 in 12 years, and with “Three Strikes” and the overcrowding we’re going to experience with that, we’re going to need to build at least three prisons a year for the next five years. Each one of those institutions will take approximately 1,000 employees.

This isn’t just a story about California. Though corrections officers’ unions outside of California are nowhere near as active as the CCPOA, many of them do advocate incarceration. (As I note below, everything is bigger in California: While private prison firms make political contributions nationwide, they, too, spend more in California.) The correctional wing of Florida’s police-and-corrections union has endorsed candidates for being tough on crime. The Michigan corrections officers’ union has opposed boot camp proposals. The New York City corrections officers’ union endorsed Gov. Pataki because he ended parole for violent felons. The New York State corrections officers’ union is said to have stymied efforts to overhaul mandatory minimum sentences. And the Rhode Island corrections officers’ union endorsed a candidate for his prosecutorial record and position in favor of tougher criminal penalties. (I am not considering the more usual demands for tougher penalties for criminals who commit crimes while in prison—a particularly salient issue for corrections officers, who are often victims of such crimes.)

Some corrections officers’ unions are combined with police unions, for instance in Florida or New Jersey. So except where (as in Florida) the corrections officers’ wing has been independently politically involved, any of these unions’ advocacy can’t be traced directly to corrections officers.

In some states, corrections officers are also affiliated with AFSCME, the general public employees’ union; AFSCME Corrections United represents 60,000 corrections officers and 23,000 corrections employees nationwide. It’s plausible that corrections officers’ concerns would be swamped by the potentially contrary concerns of public employees as a whole (who tend to be fairly liberal). And, indeed, the evidence that AFSCME has advocated incarceration is weak. AFSCME has advocated alternatives to incarceration, and the national organization has advocated legalizing medical marijuana (though of course this would only account for a tiny proportion of crime). The Oklahoma public employees’ union—also a general union—has also advocated alternatives to incarceration.

So much for public corrections officers' unions. Now let's go on to private prison firms.

Private prison firms depend, for their livelihood, on two policies: privatization and incarceration. Indeed, they admit as much to the world, in their annual reports filed with the SEC. As to privatization, The GEO Group, the second largest private prison firm, explains that “[p]ublic resistance to privatization of correctional and detention facilities could result in our inability to obtain new contracts or the loss of existing contracts, which could have a material adverse effect on our business.” As to incarceration, GEO candidly remarks:

[A]ny changes with respect to the decriminalization of drugs and controlled substances or a loosening of immigration laws could affect the number of persons arrested, convicted, sentenced and incarcerated, thereby potentially reducing demand for correctional facilities to house them. Similarly, reductions in crime rates could lead to reductions in arrests, convictions and sentences requiring incarceration at correctional facilities.

Similar statements are easily available in prison firms’ public filings. It is thus natural to suspect that prison firms may advocate both privatization and incarceration in the public square. Their political advocacy—which is extensive—mainly takes the forms of contributions to politicians and participation in the American Legislative Exchange Council (a conservative organization that drafts modern legislation), though they also testify before Congress and present arguments in the popular press. But, while it is clear that these firms advocate privatization, it is unclear that they advocate incarceration to any significant extent.

Most of the evidence of advocacy specifically in favor of incarceration has been speculative. Some writers state that it doesn’t happen, while others who are concerned about the prospect hedge their statements with terms like “may” or “are likely to.”

I noted above that the general contributions of corrections officers’ unions can’t be traced back to any specific goal, like pro-incarceration advocacy. Similarly, some commentators note private prison firms’ advocacy but don’t distinguish between pro-privatization and pro-incarceration advocacy. This blanket approach is a mistake, unless one is attacking all political involvement by prison firms. Generalized contributions to candidates, unlike targeted activities like contributions to single-issue voter initiative campaigns, are mute. Some of the industry’s contributions to politicians may be multi-purpose, for privatization as well as for incarceration. Merely advocating increased privatization raises quite different concerns than advocating changes in the criminal law itself, and certainly does not implicate the same sorts of “legitimacy” values.

Since the industry’s public statements virtually all relate to favoring privatization, there is little hard evidence on the basis of which to attribute part of their political contributions to a pro-incarceration motive. Indeed, the Association of Private Correctional and Treatment Organizations (APCTO), the industry’s trade group, speaking for its member firms, denies that the industry lobbies for increased penalties:

Individually and as an Association, we do not lobby in favor of longer sentences, so-called “three-strikes” laws, or other legislation which could result in an increase in the jail or prison population. To the contrary, the Association and its member companies encourage the use of appropriate alternatives to incarceration; provide inmates with treatment, education and rehabilitative services designed to positively impact and reduce recidivism rates; and encourage effective transitional programs for offenders upon release.

APCTO frequently endorses alternatives to incarceration, treatment programs, and other measures to reduce recidivism. Its executive director recently suggested in the Denver Post that to alleviate prison overcrowding, Colorado should “[l]ook to alternatives to incarceration that can provide treatment and rehabilitative programs to first-time, nonviolent drug and alcohol offenders,” “[r]educe recidivism by investing in the treatment, education and rehabilitation that offenders need to be successful when they leave prison,” and “[i]ncrease the likelihood that released inmates will not re-offend by providing substantive transitional programs to help released inmates adjust to the community outside the walls of prison.” (He made similar recommendations to Ohio in the Cincinnati Post.) He also suggested in the Fort Pierce Tribune and the Palm Beach Post that Florida should invest more in juvenile justice services in order to reduce the adult prison population in the long run. (He noted that APCTO’s member companies mostly provide adult incarceration services, though some would like to expand their juvenile programs.)

Even if one ignores the industry association’s official statement as self-serving and dismisses their anti-incarceration positions as PR, at most political contributions are “soft evidence” of pro-incarceration advocacy. The most we can say empirically based on such evidence is that maybe pro-incarceration lobbying happens and maybe it doesn’t. Perhaps the hard evidence is missing because the industry covers its tracks; or perhaps the hard evidence is missing because there is nothing to cover up.

Prison firms also participate in the American Legislative Exchange Council, an influential conservative organization that drafts model legislation. Both CCA and the former Wackenhut Corp. (now called the GEO Group) have been members of ALEC (and they and Sodexho Marriott, a major CCA stockholder, are prominent corporate funders of ALEC), and, over the years, at least CCA has participated in (and two of its executives have chaired) ALEC’s Criminal Justice Task Force, which drafted, among other things, a “Truth in Sentencing Act” and a “Habitual Violent Offender Incarceration Act.”

The inner workings of ALEC are hazy, and indeed, some commentators argue that the private prison industry expressly seeks out channels that are “conveniently out of public view” and “behind closed doors” to promote its pro-incarceration agenda. Presumably, prison firms work within ALEC on privatization issues: Prison privatization is one of the “major issues” of ALEC’s Criminal Justice Task Force; the Task Force has a Subcommittee on Private Prisons and has a model “Housing Out-of-State Prisoners in a Private Prison Act”; and CCA is known to have talked to the Task Force on the subject.

But this, too, is “soft” evidence; we do not know that they also work on sentencing or incarceration issues. Indeed, CCA asserts that it has not participated in, voted on, or endorsed any stand on model legislation for sentencing or crime policies within ALEC. Apparently, the only CCA official to have ever publicly taken a stand on sentencing is J. Michael Quinlan, formerly Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons and now a CCA Senior Vice President, who, after he joined CCA in 1993, told a House subcommittee that mandatory minimum sentences “are unnecessary for non-violent, non-serious offenses” and “pose[] a severe threat to prison discipline and management.”

So far, I have found a single piece of evidence of arguable pro-incarceration advocacy by a private firm. In 1995, Wackenhut chairman Timothy P. Cole testified in favor of certain amendments to the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. The main point of his testimony was to propose additional provisions (1) making clear that prison grants under the 1994 Act would “help pay for the entire range of correctional services states can provide in-house or under contract” (not merely for “alternative correctional facilities”), (2) requiring states to “show that they have all the necessary legislative authority to embark upon a comprehensive, integrated program and that they will employ the best technology at the lowest cost” (presumably to boost privatization), (3) directing the Attorney General to “give top priority to the construction of larger, ‘harder’ [i.e., higher-level security] facilities,” and (4) directing the Attorney General to give priority to states with “an executive body dedicated to the review and consideration of privatization.” During this testimony, he said the following:

“Our proposed amendment . . . would help to assure that these grants will help the states incarcerate more violent criminals and not make the state governments more dependent on federal tax dollars in the long term.” “By passing ‘truth-in-sentencing’ laws, states have begun to restore a fundamental sense of justice and fairness to our system of crime and punishment.” “The new grant program [under the 1994 Act, without the proposed amendments] is available for ‘alternative correctional facilities’ and does not recognize the urgent need for more cells in secure facilities.” “Current law encourages billions to be spent on new or retrofitted facilities that are not large enough, secure enough or efficient enough to keep the maximum number of violent criminals in prison for the least cost.”

This isn’t great evidence—Cole was really only advocating funding priorities and privatization-friendly decisionmaking. Cole’s request to divert money from alternative facilities, his kind words for truth-in-sentencing laws, and his positive attitude toward locking up violent criminals are hardly a pro-incarceration smoking gun. But this is the best I’ve found. Private prison firms may have made other statements and taken other public positions that are arguably pro-incarceration, but I haven’t found any, and to my knowledge, privatization critics have not brought them to light.

Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy, Part 7:

This post continues my series on my upcoming Stanford Law Review paper on Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy (see here for the technical paper). In the last post, I documented how there's a lot of hard evidence that public-sector corrections officers' unions advocate incarceration, and virtually no hard evidence that private firms do the same.

In this post, I consider what lessons we might draw from that. Then (below the fold), I elaborate on two curlicues of the theory (which you can skip if you're so inclined) -- first, why focus on public-sector unions and private firms only, and second, whether the public and private sectors really act strategically against each other.

* * *

As noted above, there is little hard evidence that private firms advocate stricter criminal law at all. Perhaps they do so secretly, in which case this simple model may be entirely unrealistic. Or perhaps this simple model is basically right, and the private firms are actually spending their money on a form of advocacy where the public good aspect isn’t important—pro-privatization advocacy.

Pro-privatization advocacy is an area where, obviously, the private sector can’t free-ride off the public sector, since the public sector is their enemy on that issue. If the private firms cooperate with each other, they reap all the benefits of their pro-privatization advocacy; and even if they don’t cooperate with each other, an individual firm’s pro-privatization contribution may benefit it directly to the extent that it (perhaps improperly) increases the likelihood that it will obtain a particular contract.

In real life, of course, money may be multi-purpose. I have treated “mute” campaign expenditures as though they were for some purpose—either privatization or incarceration—that was known to the donor but unknown to us. In fact, they could be for “access” to the candidate, which can be used at any time after the candidate prevails. But the model is general enough to accommodate this framework. At some point, donors will try to call in a favor. Favors cost something in terms of “political capital,” and political capital is scarce: Calling in one favor makes it harder to call in another favor. At the point where donors have to determine what to ask for, we are back in the previous model.

The “access” framework has thus only postponed the applicability of the model until after the election. One would still predict, under this model, that the smaller donors would prefer to spend their capital supporting something with more of a private-good component, like privatization, and leave the pro-incarceration advocacy to the dominant actor. And this may in fact be what happens.

* * *

Now, I'll elaborate on two curlicues of the theory. First, I'll explain why I have focused only on public-sector unions and private firms. (In short, private-sector workers aren’t unionized, and public Departments of Corrections actually want fewer prisoners.)

Next, I'll explain why I have assumed that the private firms act as a bloc instead of competing with each other or, at the opposite extreme, cooperating with the public sector. (In short, cooperation within a fairly concentrated oligopoly isn’t that difficult, because firms interact with each other a lot and have ample opportunity to punish each other for non-cooperative behavior. And private-sector firms interact with each other more than they do with the public sector, so enforcing cooperation across the whole prison industry would be more difficult. However, it turns out that how the industry cooperates, or whether it cooperates at all, doesn’t make much of a difference for the main result.)

* * *

One might ask, at this point, why I have focused primarily on two apparently asymmetrical groups: the private-sector firms and the public-sector employees. What about the employees of those firms, or the employers of those public guards?

In principle, it’s unclear a priori who would want to lobby; a case-by-case analysis of the incentives of the various parties is necessary. In this case, my choice of actors was inspired by the state of the evidence and the debate: Public corrections officers’ unions, especially in California, are known to engage in pro-incarceration advocacy; and private prison firms are alleged to do so. But let us think about this theoretically anyway.

First, the workers. No single worker has enough of a stake in the system to benefit from spending resources on advocacy to help his industry. We should only expect workers to be a significant political force if they can enforce some sort of collective action by punishing their own free-riders. The easiest way for them to do this is to require membership in or contribution to a union, which then lobbies out of members’ dues. Private corrections officers aren’t unionized in most states, and this is a sufficient explanation for why they haven’t been observed lobbying.

As I explain above, I assume that unions represent their members and seek to maximize total union rents—the difference between union and non-union wages, times the size of the public sector. The prediction that such unions would seek to increase the size of their sector is straightforward: A larger sector may mean a more powerful union and therefore potentially higher wages, benefits, or job security down the road (and perhaps—to introduce agency costs for a moment—perks for union officials). It’s possible that unions may sometimes oppose expansion of their industry—for instance, if increases in prisoners made corrections officers worse off because they weren’t accompanied by compensating wage or staff increases. This may occur in some industries, but apparently not in the prison industry. The public corrections officers’ unions seem, so far, to have been strong enough to make sure that an increased flow of prisoners has not made them worse off (even if budgets have been tight elsewhere).

Now, let’s consider the employers. Some private prison firms also run alternatives to incarceration, so it isn’t obvious that they would advocate an increased emphasis on imprisonment. Still, they may benefit from the other elements I have included in the term “incarceration”: increased illegalization, increased law enforcement, and longer sentences (once the imprisonment decision has already been made). Though increased incarceration may also increase private firms’ costs, private firms have a built-in protection against too much deterioration in their position: They don’t have to bid on a contract unless they anticipate making enough profit. So it isn’t implausible that private firms would benefit from incarceration; though of course their willingness to spend money to increase incarceration depends on how profitable they are.

What about the public employers, the Departments of Corrections? They are not players in the pro-incarceration advocacy game for a simple reason: Generally, they favor alternatives to incarceration.

The Alabama DOC commissioner has advocated sentencing reform, community correction programs, and other measures to “reverse the prison population growth trend.” The head of the Illinois DOC advocates reentry programs that would lower the prison population by countering “the awful, vicious cycle” by which recidivist parolees are re-incarcerated “before the ink is dry on their parole papers.” The Michigan DOC director concerns herself with measures to reduce the prison population and thus delay the day the state runs out of funded capacity for prison beds. The Montana DOC director candidly tells crowds that “[p]rison isn’t working,” and his department considers measures to reduce the prison population and increase community corrections. The New Mexico Corrections Department is focusing on using early parole to control its prison population. The North Carolina DOC advocates redirecting non-trafficking drug users from prison to “intermediate programs.” Ohio corrections officials complain about the high costs of mandatory minimum sentences. The Pennsylvania DOC is implementing programs “aimed at diverting less serious offenders from prison” to “free-up prison space needed for more serious offenders.” The Washington DOC secretary “is a big believer in work-release programs.” And the Wisconsin DOC secretary advocates focusing on “prevention and treatment in addition to effective law enforcement.”

This makes some sense: While it is commonly thought that agencies want to aggrandize themselves, that intuition is only a special case of a more general belief that agency officials act in their own self-interest and that their self-interest tends to be aligned with the size and power of their agencies. And increasing prisoners without corresponding budget increases to match the increasing cost of incarceration (a cost that of course includes corrections officers’ salaries, as well as health care and other factors) can easily make prison officials worse off. Thus, the interests of Departments of Corrections may not be aligned with those of corrections officers and their unions. Moreover, DOCs run both prisons and many alternative programs, so even if more inmates means more power for the DOC, it makes sense that the DOC would want to handle those inmates in cheaper ways than incarceration. Thus, it is not surprising to find prison systems arguing for alternatives to incarceration in a time of tight budgets.

* * *

All this talk of how the 10% firm acts and the profits of “the industry” assumes that the private sector, in deciding how much to spend, acts as a bloc: The private firms all cooperate with each other, but don’t cooperate with the public sector. This is possible, but it’s not the only possible story. I could have made either of two other, more extreme assumptions. First, there could be no cooperation at all—all the firms could be acting independently. Second, there could be total cooperation—all the firms could be cooperating with each other and with the public sector. This section explores the implications of these alternative assumptions and tentatively defends my decision to adopt the intermediate assumption of cooperation within the private sector but not with the public sector. But in the end, the different assumptions don’t significantly alter the bottom line.

If all firms act independently, the relevant shares are even less than indicated above. In 1999, CCA had a bit over half the market, Wackenhut (now the GEO Group) had about a quarter, Management & Training Corp. had about 5–8%, Cornell Corrections Inc. and Correctional Services Corp. each had about 5–6%, CiviGenics, Inc. had about 2–3%, and a handful of other firms had under 1%.

So, while the average private-sector share in State X may be 10%, that number is irrelevant if all firms act independently. The relevant shares may be, for instance, 6% for CCA, 2% for the GEO Group, 1% for Management & Training Corp., and 1% for Cornell Corrections . . . and 90% for the public sector. The assumption of independent firms would make it even more likely that the public sector is the dominant sector.

Now consider the opposite assumption—that everyone cooperates. A single prison industry bloc would choose an optimal total amount to maximize total industry benefit. Because the actors are still formally separate, they would also choose some way to allocate the contributions among themselves.

If the private industry had the same benefit per prison as the public sector, then total cooperation would be indistinguishable from monopoly: Because total industry benefit would be the same before and after privatization, the strategy that chooses contribution amounts to maximize that benefit would likewise be the same.

However, as I argue above, private firms aren’t terribly profitable, while public-sector unions have significant public-sector wage premiums to protect. By replacing part of the public sector with a relatively unprofitable private sector, privatization actually decreases the industry’s total benefit. Therefore, even under total cooperation, there is less to maximize; expenditures on pro-incarceration advocacy are thus less productive (just as if there were a tax rate on industry revenues); and so expenditures on advocacy still go down under privatization.

How can we tell which form of cooperation is most likely? Not being able to find explicit cooperation doesn’t mean anything: The cooperation may just be tacit. Observing the private industry’s trade association, APCTO, also doesn’t answer the question: While trade groups may provide a forum for discussing common lobbying strategies, but talk is cheap and many trade groups are ineffective; in particular, APCTO doesn’t seem to fulfill much of a coordinating function, as firms do their own lobbying and most of their own advocacy.

Even observing some actual lobbying by the major firms doesn’t answer the question: As I noted above, they may all be lobbying for privatization, which has a strong private-good component, since a firm’s contributions may increase the probability that it gets a project in the future.

On theoretical grounds, it seems at least plausible that the private firms would cooperate among themselves. They’re repeat players in a long-term process, which includes both political advocacy and their concern of bidding on prison projects; so there is ample opportunity for private firms to enforce a regime of cooperative behavior. If firms free-ride off each other in their advocacy expenditures, their fellows could punish them in the future in any number of ways—for instance, by never cooperating on campaign spending anymore, by bidding aggressively in prison auctions, or by bidding aggressively only in certain markets.

By contrast, public corrections officers’ unions may have fewer ways of punishing private firms. They don’t bid against each other in the underlying auctions, so they can’t threaten to end any cooperative behavior there. They’re bitter political adversaries in the privatization advocacy world, so again there seems to be no preexisting cooperation that can be terminated. They can threaten to not cooperate any more in pro-incarceration advocacy or to step up their anti-privatization advocacy, but this may not be as effective a threat.

For these reasons, I believe that cooperation among private prison firms is more likely than either, on the one hand, totally non-cooperative behavior or, on the other hand, totally cooperative behavior between the public and private sectors. However, because the ultimate results under any of the assumptions don’t differ that much, which assumption we choose isn’t terribly important.

Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy, Part 8:

This post is the second to last in my series on my upcoming Stanford Law Review paper on Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy (see here for the technical paper). The next post will be my conclusion (where we'll be back to nontechnical talk), so the end is in sight!

In the last post, I explained two features of the theory: Why I concentrated on private firms and public-sector unions, and why I talked as if the private sector firms colluded with each other but didn't collude with the public sector (and to what extent this matters).

The previous posts have all elaborated on the simple model I put forth in the third post of this series. That model was characterized by a severe free-riding problem: The "dominant" actor (as defined in the fourth post — basically measured by that actor's proportion of total industry benefits) does all the industry-increasing lobbying, and the lesser actors free-ride off him. Because the public-sector union seems to be the dominant actor (I explained this in the fifth post), some amount of privatization — greater than zero, but not enough to change who's dominant — would always reduce industry-increasing lobbying, because the public sector would lobby less, while the private sector would continue to free-ride.

But there are more complicated possible models. In this post, I'll explain what happens when we relax various strong assumptions from the simple model. Sometimes, relaxing an assumption doesn't change the basic qualitative result. And sometimes, instead of unambiguously predicting that lobbying would fall, it predicts that the effect of privatization on lobbying is ambiguous — lobbying could go up or go down, depending on various empirical facts. Either way, this conflicts with the critics' view that privatization would affirmatively make lobbying worse.

First, I drop the assumption that money only buys victory for a given reform or candidate, and introduce the possibility that money can also change the substance of the reform or the candidate’s position. This does not significantly alter the conclusion. Second, I drop the assumption that anti-incarceration political advocacy is fixed. I find that the effect of privatization on anti-incarceration advocacy is ambiguous (though pro-incarceration advocacy still falls with privatization).

The third and fourth sections show how privatization may have an ambiguous effect even on pro-incarceration advocacy. In the third section, I relax the assumption that all money is fungible and that all that matters is the total amount of money in the pot. Once we allow public-sector money and private-sector money to have independent effects, privatization has an ambiguous effect on pro-incarceration advocacy: Private advocacy rises, but public advocacy falls. In the fourth section, I introduce the possibility that the pattern of privatization, as we observe it today, is already the result of a political process where strong unions have successfully opposed privatization while weak unions have not. I find that exogenously increasing privatization in such an environment would likewise have an ambiguous effect on pro-incarceration advocacy, as it depends on the correlation between actors’ influence in privatization politics and their influence in incarceration politics.

The bottom line is that, if one wants to argue that privatization will increase pro-incarceration advocacy, one must argue either, from outside the model, that the model is wrong, or, from inside the model, why privatization would increase private-sector advocacy more than it would decrease public-sector advocacy.

* * *

Allowing Money to Change Candidates’ Positions.

So far, I have taken the political agenda as given: I didn’t explain where the proposed reform came from. Thus, I’ve assumed that money is important because it buys victory—for instance, by persuading voters of the benefits of the policy or the merit of the candidate. But money can also affect the agenda—by changing candidates’ positions, by inducing the sponsors of voter initiatives to propose a different initiative, and so on.

When money can affect the agenda (but the other assumptions are unchanged), the analysis is essentially the same. Suppose you are considering whether to contribute to place an initiative on the ballot. The initiative is supported by some group or other, but for specificity, let’s say it’s being sponsored by a politician. This politician may be fairly pro-incarceration himself, but he’s limited in how strict an initiative he can propose: He won’t prevail unless the median voter, whose views control the outcome of the election, prefers his proposal over the status quo. However, before the substance of the initiative is set in stone, you can move him in a more pro-incarceration direction if—by offering him money to pay for persuasive advertising—you offer him the possibility to also move the median voter.

A monetary contribution has the following effects:

Electoral influence.

As before, you benefit because, by paying for persuasion, your contribution directly increases the probability that the initiative prevails. But the contribution also moves the initiative in a more pro-incarceration direction, which cuts against the effect above. Substantive influence. Finally, you benefit if the initiative prevails, because the policy is better for you than it would have been if you hadn’t contributed.