|

Friday, May 4, 2007

Carceral Notebooks, Volume 2: Exploring the Carceral Zone with Nussbaum, Sunstein, Stone, Leitzel, McAdams, and Others.

Before unplugging and returning to my luddite existence, I wanted to share one last bit of information about the space where deviance gets criminalized. The Carceral Notebooks explore precisely that liminal space between morality and crime – focusing on the puzzles surrounding the criminal and legal enforcement of morality.

If you are interested in that space zoned carceral, you may be interested to know that a new volume of The Carceral Notebooks is just out, available to browse on the web here and also in print.

The new volume has several extremely provocative essays about the regulation of morality, especially the regulation of sexuality, as well as terrific response essays from some of our leading social thinkers. Martha Nussbaum has a wonderful essay on Narcissism and Objectification, Cass Sunstein on Equal Sex, Geof Stone on Placing Consent in Cultural and Historical Context, Jim Leitzel on Secret Deviants, and Richard McAdams on Guilt and Crime.

There is also a virtual art exhibit that accompanies the volume with remarkable artwork by Virgil Marti, Mia Ruyter and others. The artwork is arresting, and I invite you to visit the space.

Thank you to Eugene Volokh and his conspirators for inviting me to discuss my work on asylums and prisons. I’ll now return to the library and to that little green paperback Census Bureau volume, Patients in Hospitals for Mental Disease, 1923. Related Posts (on one page): - Carceral Notebooks, Volume 2: Exploring the Carceral Zone with Nussbaum, Sunstein, Stone, Leitzel, McAdams, and Others.

- Concluding Thoughts on Total Institutions: Future Directions and Critical Reflections.

- Asylums and Prisons: Race, Sex, Age, and Profiling Future Dangerousness.

- Institutionalization vs. Imprisonment: Are There Massive Implications for Existing Research?

- Mental Hospital, Prison, and Homicide Rates: Some More Analyses.

- Mental Hospitalization and Prison Rates in Western Europe:

- On Mental Health Commitments and the Virginia Tech Shooting:

- Bernard Harcourt Guest-Blogging:

Adam Cohen on Why Debra Yang Resigned as U.S. Attorney:

'Tis the season for speculation about why various U.S. Attorneys left their jobs in the last year. Some of the speculation seems plausible, and some of it seems off. My vote for the most implausible theory is one floated by Adam Cohen in The New York Times today about Debra Yang, the Republican U.S. Attorney for the Central District of California, who left the U.S. Attorney's Office to take a partnership at Gibson Dunn & Crutcher. If I understand Cohen's suggestion correctly (it's the second in his list, starting with "a second possibility"), Cohen wonders whether there might have been a secret conspiracy between Gibson Dunn and the Bush White House to get rid of their mutual enemy, Yang, by giving her a partnership at Gibson plus a $1.5 million signing bonus. With enemies like that, who needs friends? UPDATE: Gibson Dunn Partner Randy Mastro responds over at the WSJ Law Blog. As you would expect, Mastro is parroting the Bush Administration line: he has the gall to just deny the conspiracy outright. Of course, the denial is being published in a blog run by the ultra-conservative Wall Street Journal, which is probably in cahoots with the White House and Gibson anyway.

"No Political Candidacy" Clauses for Actors?

Michael Froomkin (discourse.net) points to an L.A. Times story about how "about how Law & Order reruns might have to be pulled if Fred Thompson runs for President," and asks: If stations are so afraid of having to give equal time for other candidates that they’d rather pull the episodes, then surely it would be economically rational for the studios to put a routine “no running for office” clause in actors’ contracts that would apply so long as the reruns are showing?

My question is whether that term would be enforceable: would it be against public policy? Or maybe fall to the same sort of doctrines that disfavor non-compete clauses that last more than a few months to (at most) a couple of years?

Well, California is one of about ten states that expressly or implicitly protect private employees from discharge for certain kinds of political activities. Cal. Labor Code § 1101 provides: No employer shall make, adopt, or enforce any rule, regulation, or policy:

(a) Forbidding or preventing employees [or applicants for employment, according to a California Supreme Court decision] from engaging or participating in politics or from becoming candidates for public office.

(b) Controlling or directing, or tending to control or direct the political activities or affiliations of employees [or applicants for employment]. The statute is written categorically, with no exceptions. One federal district court decision, Smedley v. Capps, Staples, Ward, Hastings & Dodson, 820 F. Supp. 1227, 1230 n.3 (N.D. Cal. 1993), stated that there might be an exception "when the employee's political activities are patently in conflict with the employer’s interests"; but I don't think that's a correct interpretation of the statutory text, or of Mitchell v. International Ass’n of Machinists, 196 Cal. App. 2d 796 (1961), the case that Smedley cited as precedent for its assertion.

So it sounds like such "no political candidacy" rules would likely violate the California statute, and would thus be illegal when it comes to employees working in California. Do they apply to actors who are ostensibly hired as independent contractors? I don't know the answer to that, though I suspect that simply labeling workers "independent contractors" wouldn't suffice to exempt them from coverage.

What if Law & Order employees are governed by New York law? New York is one of the other states with such a statute, N.Y. Labor Law § 201-d; this reads, in relevant part: (1) (a) “Political activities” shall mean (i) running for public office, (ii) campaigning for a candidate for public office, or (iii) participating in fund-raising activities for the benefit of a candidate, political party or political advocacy group ....

(2)(a) ... [No employer may discriminate against an employee or prospective employee] because of ... an individual’s [legal] political activities outside of working hours, off of the employer’s premises and without use of the employer’s equipment or other property [except when the employee is a professional journalist, or a government employee who is partly funded with federal money and thus covered by federal statutory bans on politicking by government employees] ...

(3) [This section] ... shall not be deemed to protect activity which ... creates a material conflict of interest related to the employer’s trade secrets, proprietary information or other proprietary or business interest [such as when the German National Tourist Office fired an employee for becoming known as the translator of some Holocaust revisionist articles -EV].... A rule that bars employers from engaging in politics would likely be treated as presumptively impermissible discrimination based on their legal political activities. But that presumption would likely be rebutted in a situation such as the one Prof. Froomkin describes, because political activities that seem to legally mandate that an employee's work product no longer be salable would likely qualify as involving "a material conflict of interested related to the employer's ... business interest."

If anyone knows more about this issue, please post about it in the comments.

Talking About Forced Sex of Avatars = Crime?

Some people call it "virtual rape," but it strikes me as so far removed from the real thing that even including the adjective "virtual" leaves the phrase with a misleading connotation. In any case, Wired commentator Regina Lynn reports:

Last month, two Belgian publications reported that the Brussels police have begun an investigation into a citizen's allegations of rape — in Second Life....

Can anyone who speaks Dutch tell us more about these accounts (here and here)? I'd like to know whether they seem real or jokes (a possibility the Wired item flags), and also precisely what laws were allegedly violated.

I should note:

One can easily imagine a game in which such behavior is cause for expulsion, or breach of a player's contract; but I take it that this wouldn't make it a criminal violation. The speech might also be punishable as a threat if it is reasonably perceived as a threat against the real person whose avatar is involved, for instance, if it appears that the speaker knows who the avatar's real-world user is, and in context the statements are reasonably understood are threatening the user. But this would be unlikely if there's no reason to think that the user's identity is known. (Note also that under U.S. law, it's possible that for the speech to be a threat there must also be evidence that the speaker intends it to be perceived as a threat; I can't speak to Belgian law.) Sufficiently explicit talk of sex might be seen as punishable pornography, depending on the country's laws. It's conceivable that it would even qualify as unprotected and criminally punishable obscenity in the U.S. (and the targeting of the statement to an unconsenting player might help support this position, if the "prurient interest" and "patent[] offensive[ness]" prongs are seen as considering the context of the speech as well as the content); but it would have to be pretty explicit for that to happen, I think.

In any event, I'm curious what exactly the legal theory is in the Belgian investigations, if there really are investigations and there really is a legal theory.

Thanks to John Rayburn for the pointer.

UPDATE: Many thanks to Dutch-speaking reader James Wallmann, who writes: The two news items are virtually identical. Here are the translations:

First link: Federal Computer Crime Unit Patrols in Second Life

The Brussels Public Prosecutor’s Office has asked investigators of the Federal Computer Crime Unit to patrol in Second Life.

In the virtual world of the computer game[*] a personality was recently “raped.” Following the virtual rape the Brussels police opened a file. “It is the intent to determine whether punishable acts have been committed,” according to the federal police. The Public Prosecutor’s Office was also alarmed. At the vice section acting officer Verlinden opened an informational investigation into the details. * Note use of diminutive suffix (-etje), which I didn’t translate, suggesting this is something trivial or for kids....

Second link: Brussels Police to Patrol in Second Life

The Brussels Public Prosecutor’s Office has asked investigators of the Federal Computer Crime Unit to patrol in Second Life. This according to De Morgen. In the virtual world of the computer game[*] a personality was recently “raped.” Following the virtual rape the Brussels police opened a file. “It is the intent to determine whether punishable acts have been committed,” according to the federal police. The Public Prosecutor’s Office was also alarmed. At the vice section acting officer Verlinden opened an informational investigation into the details. * Note use of diminutive suffix (-etje), which I didn’t translate, suggesting this is something trivial or for kids.

Real or jokes? Your guess is as good as mine. I suspect that the anonymous reporter thinks this investigation is a bit silly, but perhaps just the facts are being reported. As you see from the translations, nothing is said about what laws may have been violated.

Three of the comments in the first link were amusing: "Will the perpetrator receive a virtual punishment?" and "For heaven's sake, what's going on here? Normally citizens have to move heaven and earth to get the police involved in something. Gentlemen, this is virtual! Perhaps the Public Prosecutor's Office doesn't know what this means." and "Ah, that lovely feeling you get when you hear that your tax dollars are being wisely spent." The commentators certainly took the article at face value, not as a joke.

Russian Speakers Are Superior!

At least, apparently, at telling shades of blue apart (thanks to Paul Hsieh (GeekPress) for the pointer) -- and the theory is that it's because conventional Russian "divide[s] what the English language regard as 'blue' into two separate colours, called 'goluboy' (light blue) and 'siniy' (dark blue)."

Obviously, English has many words for many shades of blue, too, but there is indeed a difference between how casual English speech and casual Russian speech treat the colors. In English, "blue" would be commonly used for light blue or dark blue, in a way that isn't so for pink and red. In Russian, one would normally distinguish "goluboy" (light blue) from "siniy" (dark blue) just as one would distinguish "rozoviy" (pink) from "krasniy" (red). In any case,

Researchers led by Jonathan Winawer of Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge presented Russian and English speakers with sets of three blue squares, two of which were identical shades with a third 'odd one out'. They asked the volunteers to pick out the identical squares.

Russian speakers performed the task more quickly when the two shades straddled their boundary between goluboy and siniy than when all shades fell into one camp. English speakers showed no such distinction.

But wait! There's one item the Nature article didn't note: In Russian, "goluboy" is also a slang term for a male homosexual. Coincidence? Or conspiracy?

Will the ABA Eliminate Tenure Requirements for Accreditation:

Inside Higher Ed says "maybe" (hat tip: Instapundit). Given that I don't think the ABA should be in the accreditation business to begin with (at least not to the extent that government relies on such accreditation to decide who gets to take the bar, and who gets student loan funding), a fortiori I'm against the ABA's enforcement of ANY particular standard.

But I specifically agree that giving full-time "regular" faculty tenure (much less clinicians, deans, and library directors) should not be a requirement for accreditation. As a commentor on the IHE site notes,

Once tenured, there are many in the academy who adopt an entitlement mentality whereunder they rarely or never do research, teach classes from the same notes year after year until they are well past stale, and fail to meet minimal standards of service and compliance, yet are largely untouchable. And why should a library director or a dean, both of whom are much more administrators or fund raisers than academics, be given such absolute protection if they screw up in their jobs and are not quality teachers/scholars?

I know that when I was on the teaching market, I was amazed when looking at law school brochures to see how many senior faculty at various schools had published nothing beyond an occasional state bar journal article for many years running, and I continue to be surprised at how many law profs seem to manage to have more or less full-time law practices on the side (the latter in violation of ABA rules!).

Also, there are many professors (and potential professors) out there who are fine teachers, but really don't have much to say scholarship-wise. Current ABA standards require that they be given low teaching loads, and also be eligible for tenure, which means that they are forced into a "scholar" persona even if it doesn't fit. Lawyers who are ready, willing, able, and eager to teach are discouraged from joining the academy because they aren't ready, willing, able, and eager to write turgid law review articles for the sake of writing them, just to meet tenure standards. The overall result is a lot of largely unread mediocre scholarship published in obscure law reviews, and a lesser teaching environment for students.

I expect that with or without ABA requirements, law schools that consider themselves to be research institutions will continue to have tenure for their research-oriented faculty. But abolition of the requirements will allow law schools that see themselves primarily as teaching institutions to pursue that goal in a far more efficient manner. Academic freedom is important, but tenure is hardly the only way to protect it (and, in fact, the greatest violations of academic freedom seem to occur when candidates are considered for positions; faculties tend to be much less tolerant of applicants with "deviant" ideological views than of their colleagues).

Profile of the DC Madam's Lawyer,

in today's Washington Post. He sounds like the perfect attorney to hire if you're charged with running a high-class prostitution service; the evidence against you is overwhelming; and your primary goal at this stage is to make sure your case becomes a memorable news story so you can sell your book and movie rights for a lot of money. (The federal "son of sam" law only applies to espionage offenses and crimes that cause physical harm, so I gather Palfrey can keep whatever money her book and movie rights will bring.)

Did Online Resources Help Cause A Decline in the Supreme Court's Docket?:

According to the Associated Press, Chief Justice Roberts delivered remarks at the Alaska Bar Association annual convention that included an interesting theory for what has contributed to the decline in the Supreme Court's docket in recent years: thanks to on-line resources, lawyers and lower courts can find existing lower court precedents more easily, resulting in fewer circuit splits for the Supreme Court to resolve. The AP story doesn't give the details of the argument — it only has a sentence on it — but the idea seems plausible to me. It's much easier to find relevant lower court caselaw on Westlaw or LexisNexis than it was to find those cases using just the books. That may mean that lawyers and law clerks are more likely to find the right cases, circuit courts and state supreme courts are more likely to consider them, and the law is more likely to end up being uniform across different jurisdictions. Thanks to How Appealing for the link.

Concluding Thoughts on Total Institutions: Future Directions and Critical Reflections.

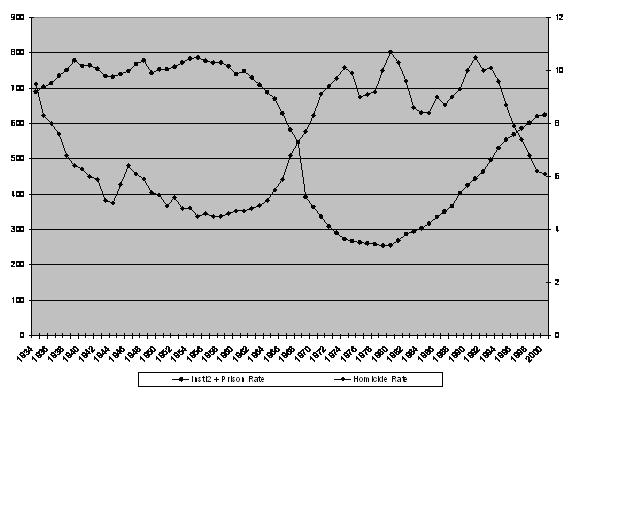

I conclude this series of web logs where I began — with that haunting graph of the asylum and prison populations in the United States during the twentieth century (rates per 100,000 adults):

Chris Uggen, chair of the sociology department at Minnesota, asks on his public criminology blog: “Shouldn't sociological criminologists be able to offer some explanation for the figure at left, showing the aggregate rate of institutionalization for prisons and mental hospitals?”

The figure does, indeed, call out for explanation. But my sense is that the graph itself and the state panel regressions do more to undermine confidence in our conventional explanations and accepted wisdom, than they do to stabilize them.

It may simply be too early to offer answers. We may need first to rethink and study afresh the notion of total institutions. So let me suggest here a few directions for further research and a question regarding the larger theoretical framework.

First, I think we need to place the demographic differences between the two populations in a richer historical context. Many readers immediately question my findings because of the demographic contrast between the asylum and prison populations. But there may be more to the picture. On the issue of racial compositions, for instance, the national counts may mask important differences at the state and regional level.

The early surveys by the Census Bureau are revealing in this respect. Aggregated to the national level, African-Americans represented a small fraction of residents in mental hospitals enumerated on January 1, 1923 — 7.6% to be exact — and had a relatively low institutionalization rate (192 persons per 100,000 African-Americans). Whites in contrast represented 92.9% of mental hospital residents and had a significantly higher ratio of 259.8 per 100,000 whites. But things look very different within and between states and regions.

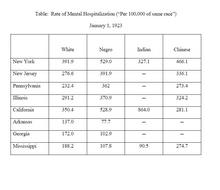

The New England and Pacific regions had high rates of black institutionalization, in fact far higher than white institutionalization in those regions, and also far higher than black institutionalization in the South. The Census Bureau in 1932 explained why: “This is undoubtedly due to the lack of adequate hospitals for negroes in the South. In the parts of the country in which negro patients are admitted to State hospitals without discrimination, the rate for negroes generally exceeds that for whites. In Massachusetts, for example, the rate for resident negro patients is 644.4 and for resident white patients, 408.8.” Here are some other state breakdowns (in rates “Per 100,000 of same race”):

Notice how the comparative rates differ as between states and regions. Clearly, racial demographics varied at the state level and will require more nuanced analysis.

Second, we need to explore in greater depth the relative magnitudes of the different possible effects. In the state panel data regressions, there are interesting clues about other potential explanations. I've already discussed here the issue — or non-issue — of capital punishment. But there are other explanations to investigate.

The size of the youth population seems to play an important role in my regressions, which is consistent with what many criminologists have argued (see here and here). (Some economists do not agree, see here and here). What is particularly interesting about my results is that the effect shows up with the 20 to 24 cohort in the most complete models, but not with the 15 to 19 cohort. This suggests that the actual ages chosen may have significant impacts on the results.

The race effects are also remarkable and, in all likelihood, have to do with high victimization rates in the African-American community, as Lawrence Bobo at Stanford suggests here in "A Taste for Punishment." The negative effect of urbanization is surprising, but may be an artifact of a very loose definition of urbanity. The Census Bureau defines “urbanized areas” very broadly to include areas that have a density of 500 persons per square mile. The gradual lowering of the urban threshold may account for these surprising results.

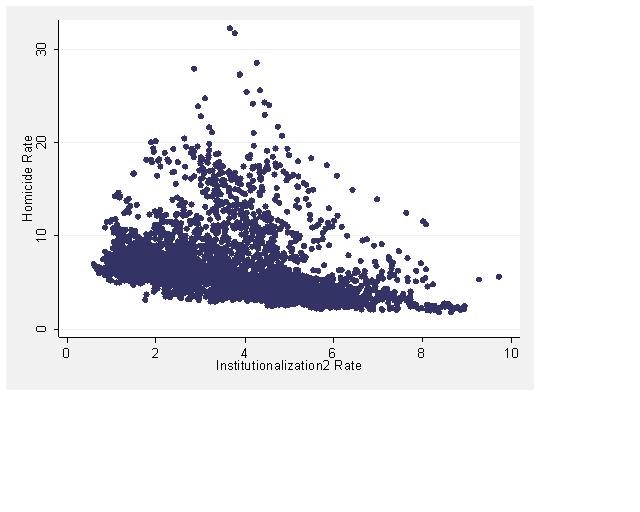

The key question, though, is how these potential explanations compare in magnitude to each other and, more importantly perhaps, as compared to sociological theories of neighborhood effects, social disorganization, social control, subcultural theories, etc. How does aggregated institutionalization compare to Robert Sampson's measures of collective efficacy and social cohesion in the size of its effect on crime or unemployment or education? Is it possible that institutionalization may actually dwarf those other effects, especially when we investigate a lengthy time period such as 1934 to 2001?

This raises a larger theoretical question about kinds of explanations. The fact is, aggregated institutionalization is about social physics. The term "social physics" may sound nineteenth-century — rightly so. It was first used by Auguste Comte to refer to what is now the discipline of sociology, though Comte abandoned the term when the statistician, Adolphe Quetelet, started using it in a more narrow statistical sense to refer to the “homme moyen” (the average man).

In reappropriating the term here, I would define social physics narrowly as social theories that are necessarily true as a result of the physical nature of our mortal existence, in contrast to theories that depend on the intermediation of human consciousness and decision-making. By way of illustration, consider six theories now central to sociological and economic criminology: (1) rational choice theory, (2) the broken-windows theory, (3) legitimacy theory, (4) incapacitation theory, (5) youth demographics, and (6) the abortion hypothesis. The first three operate through the intermediary of human consciousness. In each case, the theory depends on actors believing certain things and conforming their behavior to those beliefs. In contrast, the last three theories involve only social physics — physical restraint in the case of incapacitation or cohort size in the latter two cases.

Depending on the magnitude of the effects, it may turn out that social physics explain far more than theories of rational choice and social influence. (I discuss this idea here in a a new essay). This raises a troubling question: If social physics have far greater explanatory power, then why have we spent so much of the twentieth century developing socio-cultural and political explanations of deviance — theories of deviant subcultures, disorderliness, social disorganization, collective efficacy, anomie, social conflict, to name but a few? If the dominant factor is simply the rate of total institutionalization qua incapacitation or the size of youth cohorts, then why have we spent so much time trying to identify and shape social relations and social processes?

The answer to this puzzling question — should it arise — may lie in our schizophrenic relationship to punishment that is so glaringly reflected in the arresting figure of asylum and prison populations.

Related Posts (on one page): - Carceral Notebooks, Volume 2: Exploring the Carceral Zone with Nussbaum, Sunstein, Stone, Leitzel, McAdams, and Others.

- Concluding Thoughts on Total Institutions: Future Directions and Critical Reflections.

- Asylums and Prisons: Race, Sex, Age, and Profiling Future Dangerousness.

- Institutionalization vs. Imprisonment: Are There Massive Implications for Existing Research?

- Mental Hospital, Prison, and Homicide Rates: Some More Analyses.

- Mental Hospitalization and Prison Rates in Western Europe:

- On Mental Health Commitments and the Virginia Tech Shooting:

- Bernard Harcourt Guest-Blogging:

James Comey's Testimony, and His Continuing "Errring on the Side of Neutrality and Independence":

Former Deputy Attorney General James Comey testified before the House Judiciary Committee today, and his recollection of the work of the 8 fired U.S. Attorneys stood in sharp contrast to Attorney General Alberto Gonzales's official line. The gist of Comey's testimony: Most of the fired U.S. Attorneys were outstanding, and they certainly weren't fired for what you would traditionally think of as "performance" reasons. Listening to Comey's testimony reminds me of this fascinating 2004 Legal Times story (that I blogged about here and here) on why the universally-respected Comey was not likely to be nominated for the Attorney General slot when Ashcroft stepped aside. From the introduction of the 2004 story, with emphasis added: There are a number of candidates who could be tapped to replace John Ashcroft as attorney general if President George W. Bush wins re-election. But perhaps the most obvious choice, Deputy AG James Comey, almost certainly will not be.

Since his confirmation as the No. 2 Justice Department official in December 2003, sources close to the department say Comey has had a strained relationship with some of the president's top advisers, who feel that Comey has been insensitive to political concerns.

According to several former administration officials who spoke on the condition of anonymity, tensions were sparked when Comey appointed a special prosecutor to take over the investigation into whether a White House official leaked a Central Intelligence Agency operative's name to the media. The special prosecutor, U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald, has doggedly pursued the probe, and several administration officials, including presidential adviser Karl Rove, have been questioned by prosecutors.

Distrust of Comey deepened after some of his early staff picks were vetoed by the White House for not having strong Republican credentials, sources say.

"The White House always wants to make sure the administration is staffed with people who have the president's best interests at heart. Anyone who resists that political loyalty check is regarded with some suspicion," says one former Bush administration official. "The objective in staffing is never to assemble the best possible team. It is to assemble the best possible team that supports the president."

Earlier this year, after the disclosure of internal administration memos that seemed to condone the torture of suspected terrorists overseas, Comey pushed aggressively for the Justice Department's memos to be released to the media and for controversial legal analyses regarding the use of torture to be rewritten.

In a deeply partisan administration that places a high premium on political loyalty, sources say Comey — a career prosecutor and a former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York — is not viewed as a team player.

"[Comey] has shown insufficient political savvy," says the former official. "The perception is that he has erred too much on the side of neutrality and independence." Comey still has this "problem," it seems. Of course, the White House's eventual pick, Gonzales, does not.

Thursday, May 3, 2007

City Threatening to Sue State for Negligent Failure to Legislate:

The Philadelphia Daily News reports:

What's held [the Philadelphia City Council's gun control agenda] in check is that only the commonwealth can legislate in the area of firearms, and unless the General Assembly will delegate power to the city, Council's actions would be dead on arrival....

[Now, Councilman Darrell Clarke says the Council] is preparing to file a legal complaint related to the Legislature's inaction....

Asked how Council can move forward on the bills without a state enabling law, Clarke said, "We think that with our complaint, we will show in our theory that the state has been negligent in terms of enacting good-sense legislation. We think we have a compelling case." ...

What a great theory! If you think the state has been negligent in terms of enacting good-sense legislation, why, just sue the state for negligent failure to legislate. Once it does that, and some other city or organization thinks the state has been negligent in terms of enacting bad-sense legislation, it can sue the state for negligent legislation.

Then the courts can just decide what makes the best sense, and that'll be that. No need for them to limit themselves to any areas specially removed from the political process by a constitutional provision (say, the right to free speech, the right to bear arms, city home rule as assured by some express state constitutional provision, and the like). Just apply a general "did the legislature fail to enact good sense legislation? / did it enact bad legislation?" test, potentially covering any question under the sun. Cool.

Thanks to Guy Smith for the pointer.

Federalism and Tort Reform:

My colleague Michael Krauss has an excellent column in the Wall Street Journal on federalism and tort reform (subscription-free excerpt available here). Currently, states with unusually stringent tort liability rules can impose them even on products that their residents purchased out of state. As Michael explains:

A manufacturer might want to charge higher prices in West Virginia to cover the legal 'premium' it must pay for unavoidable product-liability rules there. It wouldn't work. Mountaineers could simply purchase the product in neighboring Maryland and bring it back home — and current jurisdictional rules essentially provide that West Virginia tort law will apply to all accidents occurring there, regardless of where the consumer bought the product.

"West Virginia consumers, in other words, obtain the same tort 'coverage' — but for a lower premium — if they buy the product in Maryland. As a result, manufacturers aren't able to lower the price of their products in Maryland to reflect that state's less onerous (or ridiculous) product liability rules, because they may end up incurring the higher liability costs of West Virginia. I believe this helps to explain the product liability mess in the U.S. We have more product liability than we want because of a beggar-thy-neighbor 'Byrd Effect.'

He proposes a federalist solution to the problem:

Suppose, however, a federal law declared that the laws and rules governing product liability applicable to a given product are the rules of the state where that product was first sold at retail.

Thus, if a West Virginian bought his lawn mower in Maryland, it would be Maryland law that determined product liability, even if an accident involving an alleged defect happened later in West Virginia . . . Manufacturers could now price goods in each state to reflect that state's liability rules — allowing consumers to pay for the liability protection they wanted. Competition would provide consumers with knowledge of what this all means. West Virginia retailers would have a keen incentive to explain to consumers how they receive greater protection — in return for a higher purchase price . . .

Of course, consumers might not want to pay for this extra protection. Suppose that the West Virginia retail price of a lawn mower includes a premium reflecting the outlays required by a product liability rule requiring full compensation to a consumer injured through his own misuse of a product. The consumer might say, 'Thanks but no thanks. I'll take my chances,' and buy his lawnmower in Maryland, where this 'misuse protection' is not bundled into the purchase price. West Virginia retailers lose sales; and if the losses became apparent, these retailers would be well placed to pressure political representatives to modify liability rules so as to better reflect consumers' actual preferences.

Michael's proposal is better than the traditional conservative approach of trying to impose one-size-fits-all tort reform through the federal government. There is no reason to believe that the feds will come up with a good solution that reflects the diverse needs of different states. Even if they do, Congress will have little incentive to make efficient adjustments to the rules over time. Michael's approach is also better than the status quo, which in effect allows the most pro-plaintiff states to set prices and product standards for the entire country. States should be allowed to set tort policy for products sold within their own borders. Interstate competition and consumer choice will give them strong incentives to avoid overreaching, while simultaneously addressing legitimate safety concerns. But they should not be allowed to in effect impose their tort liability rules on products sold elsewhere.

More generally, Michael's argument reflects an important theme in the emerging literature on federalism: in order to achieve the benefits of interstate competition and diversity, we must limit not only the powers of the federal government, but also the power of state governments to control people and businesses outside their borders. Northwestern law professor John McGinnis and I made this case in our 2004 article Federalism vs. States' Rights. Most people - even most constitutional lawyers - think of federalism as a system of limitations on central government power. But in many situations, it actually entails limits on the power of state governments as well.

Bush to veto expanded hate-crimes law:

The bill passed the House today, 237-180. It goes on to the Senate. A statement released by the administration says that Bush's senior advisors will recommend a veto. That's not quite the same as saying he will veto it, but it's pretty close. If he does, it would be the third of his presidency, after stem cells and a timetable for withdrawal from Iraq. The text of the bill is here.

The administration's given reasons are that the law is unnecessary, an intrusion on federalism, and constitutionally questionable as an exercise of federal power. I expressed similar reservations in a post here about the bill two months ago. To its credit, the administration is avoiding the common and I think mistaken complaint that the bill would punish speech and thought. Anti-gay organizations, like Concerned Women for America, will certainly be happy about this. But their glee is insufficient reason to support the bill.

Andrew Sullivan, who like me opposes hate crimes laws as a general matter, complains that Bush's veto of this bill represents a double-standard under which gays are just about the only commonly victimized group left out of the special protection federal law already provides. That might in fact be the sort of pandering to anti-gay bigotry that's going on here and, if so, the administration deserves to be criticized not for the veto but for the malign motive behind it.

The problem with this criticism, however, is that the bill does much more than simply add "sexual orientation" to the existing federal law on hate crimes passed in 1968. It's a whole new statute. Protecting gays is only one element, though the most publicized. The bill considerably expands federal jurisdiction over hate crimes in general, for all categories, by eliminating the current requirement that the crime occur while the victim is engaged in a federally protected activity. That jurisdictional limitation has kept federal involvement very limited in an area where state authority has traditionally reigned. The new law also calls for more federal resources to be expended on all classes of hate crimes. The veto of an amendment merely adding sexual orientation to existing federal law would pretty clearly reflect an anti-gay double-standard. A veto of this much more comprehensive bill does not.

To test this proposition, and to put gays on a par with other groups often targeted for hate crimes, Congress could simply amend the 1968 federal hate-crimes law to add protection for sexual orientation. Then we'll see what the President does.

UPDATE: Marty Lederman has some thoughts on an interesting wrinkle in the administration's constitutional objections to the bill.

Nebraska Supreme Court Takes Over Defense of Capital Defendant:

Carey Dean Moore has been convicted of capital murder and has decided not to raise any more challenges to his sentence or method of conviction. Yesterday, however, the Nebraska Supreme Court has on its own decided to bar the state from executing Moore, at least for now. The reason: the Justices are considering the constitutionality of lethal injection the electric chair in another case, and the judicial need "to ensure the integrity of death sentences in Nebraska . . . requires Moore to cede control of his defense" to the Justices of the Nebraska Supreme Court until that issue is settled. The Court explains that the power to take over Moore's defense follows from the Court's "inherent judicial power, which is that power essential to the court's existence, dignity, and functions." The Justices therefore filed and granted their own motion to withdraw the death warrant they had issued that had allowed the state to execute Moore. There's nothing unconstitutional about this, as far as I can tell. But it does seem rather strange. For more on the decision — including the reaction of Moore, his attorney, victims of the family, and death penalty activists — the Omaha World-Herald has some details. Thanks to James Creigh for the link.

Dealing with Gonzales:

Two interesting op-eds in today's New York Times offer ways to deal with the troubling persistence of Attorney General Alberto Gonzales. One calls for Congress to impeach Gonzales:

A false claim not to remember is just as much a lie as a conscious misrepresentation of a fact one remembers well. Instances of phony forgetfulness seem to abound throughout Mr. Gonzales’s testimony, but his claim to have no memory of the November Justice department meeting at which he authorized the attorney firings left even Republican stalwarts like Jeff Sessions of Alabama gaping in incredulity. The truth is almost surely that Mr. Gonzales’s forgetfulness is feigned — a calculated ploy to block legitimate Congressional inquiry into questionable decisions made by the Department of Justice, White House officials and, quite possibly, the president himself.

Even if perjury were not a felony, lying to Congress has always been understood to be an impeachable offense.

Assuming for the sake of argument that lying to Congress about a matter on which Gonzales might have refused to testify amounts to an impeachable "high crime [or] misdemeanor," it's not necessarily the case that Gonzales lied. His claims not to recall key events in the firing of the U.S. Attorneys may have been, in descending order of seriousness, (1) conscious lies designed to thwart congressional oversight and shield wrongdoing by Gonzales or the White House, (2) conscious lies designed to protect what Gonzales believed were matters protected by executive privilege (without actually claiming the privilege), regardless of their effect on congressional oversight or on protecting allies, (3) gross nonfeasance or incompetence, which caused him to fail to devote sufficient attention to the matter, and thus not to remember these events because he was concentrating on others, or (4) genuine forgetfulness. I think something like #2 or #3 is most likely. In the case of #2 Gonzales should have invoked a politically costly executive-privilege claim. All four are sufficient reason for Gonzales to resign.

But as a prudential matter I am reluctant to say at this point that Congress should begin impeachment proceedings, even if it has the right to do so. For better or worse, impeachment is the nuclear option in American politics. Only one other executive cabinet member has ever been impeached. No attorney general has ever been impeached; when they get in bad trouble, they tend to resign, which Gonzales may yet do. Impeachment proceedings against an AG would be a time-consuming and absorbing national drama which, however constitutionally warranted, may still be avoided through resignation. Impeachment proceedings would increase the political pressure on Gonzales to resign, but they might also cause the administration and its supporters in Congress to dig in their heels against a "partisan" Democratic Congress.

The main role of Congress here is not to impeach, but to make sure that when the Executive branch exercises its power in a way that undermines confidence in the Justice Department, it is called to political account. That is what has happened and is happening in the case of Alberto Gonzales, even with his claims of amnesia, which are bringing public ridicule and contempt upon him and the administration. My hunch is that he will try to find a face-saving way to resign in the next few months. The question is whether waiting that long will do so much damage to the functioning and credibility of the DoJ that we ought to begin impeachment proceedings (which might also take months), to increase the pressure on him to go sooner. I don't think we're there yet.

The second op-ed is more radical, calling for structural reform at the Justice Department:

I suggest we begin by making the attorney general job no longer a cabinet position. . . .

The solution is to have the attorney general appointed to a fixed term — say, 15 years — that wouldn’t be coterminous with the tenure of the president who appoints him. As with the director of the F.B.I. (a 10-year term) and the chairman of the Federal Reserve (a four-year, renewable term), the appointment would be made by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate. Congress’s oversight would ensure that no political hack or crony of the president could be handed the job.

Likewise, the 93 United States attorneys should not be political apparatchiks, but talented lawyers selected half from Republican ranks and half from Democratic, following the system used for regulatory bodies like the Federal Communications Commission. These men and women should also be subject to Senate confirmation.

Changes in the occupant of the White House should not affect the way justice is administered. If the Gonzales mess ends up giving us an apolitical Department of Justice, the American people will be well served.

I have several concerns about this proposal. First, while the term of the AG would be longer, the process by which she's chosen would be basically the same. President nominates, Senate confirms. If Congress hasn't already exercised sufficient oversight to ensure that hacks and cronies aren't appointed, it's not clear why that would change much (though a longer term for the AG might make Senators take their job somewhat more seriously). What seems most to drive real oversight on appointments is not the particulars of Congress's structural role but whether it is in the hands of the opposing party. That partisan reality is unchanged by the proposal.

Second, I'm not sure we'd profit from an AG "independent" of the president and removable (presumably) only by impeachment. The experience of the FBI, for example, does not inspire much confidence. Incompetence and abuse of power come just as easily with "independence" as with hackery. I'd be concerned about a tyrannical, long-serving AG in the mold of J. Edgar Hoover who couldn't be removed easily by impeachment or forced to resign.

Third, I don't see how the proposal would really give us an "apolitical" Justice Department so much as a "bi-political" one, with both Democrats and Republicans getting their favored candidates in particular U.S. Attorney offices.

Finally, the proposal would represent a serious diminition of the President's power and duty to take care that the laws be faithfully executed. It's not that the proposal is unconstitutional. It's that it's constitutionally unwise. It's a break with two centuries of tradition, under which we have usually had acceptable and competent AGs and sometimes outstanding ones. We may think that President Bush has abused his authority, made extravagant claims about executive power, and even violated the laws he is supposed to enforce. But he will not always be the president. When there are other ways to deal with his excesses, as there are, it seems to me short-sighted to base fundamental reform of the executive branch on the sometimes disquieting experience of his presidency.

We're Getting Warrants Now, But That's the President's Call, DNI Says:

The NSA domestic surveillace program has been out of the news ever since it was announced in January that the Bush Administration had agreed to seek FISA warrants for such surveillance rather that try to conduct it outside of FISA. In a hearing earlier this week on amending FISA, Director of National Intelligence Michael McConnell made clear that in the Bush Administration's view, this is completely at the President's discretion. According to McConnell, the Administration still takes the view that FISA is unconstitutional and that it has Article II authority to ignore FISA, but it just has decided not to exercise that particular authority at this particular time. According to McConnell: "Article II is Article II, so in a different circumstance, I can’t speak for the president what he might decide." (Hat tip: Balkin)

The Baseball Economist:

I just recently read John Charles Bradbury's marvelous new book The Baseball Economist: The Real Game Exposed. J.C. is currently an economics professor at Kennesaw State University and writes the brilliant blog Sabernomics. I also had the pleasure of being the outside reader on J.C.'s PhD dissertation, which was a splendid public choice analysis of legislative bicameralism (which had the added virtue of reinforcing some of the themes in my Seventeenth Amendment scholarship).

J.C.'s blog is entitled "Sabernomics" and the idea behind the blog and his book is to combine standard sabermetrics analysis of baseball statistics with economics to generate hypotheses that can be tested. So, for instance, he tests the proposition of whether having "protection" by a good on-deck hitter helps the batter at the plate by making the pitcher give him something to hit (Bradbury says no, contrary to conventional wisdom). He also discusses the method by which player's on-field contributions can be converted into a measurement of their actual financial value to their team (which the Wall Street Journal also discussed a few weeks back). He also concludes that there really was a "Leo Mazzone" effect on pitchers with the Braves. And I think my favorite chapter is "The Extenct Left-Handed Catcher" which I think is the cleverest chapter in showing how adding clear economic thinking can help think through some baseball puzzles that sabermetrics alone can't answer.

It is really a great book and I think VC baseball fans will enjoy it. And if you enjoyed this, you'll certainly want to move on to read his empirical work on bicameralism (ok, maybe that part is just me).

Accountability to Colgate Alumni Initiative:

There appears to be an interesting movement afoot among Colgate alumni, the "Accountability to Colgate Alumni Initiative." The goal of the initiative, as their website explains it, is "to ask the Board of Trustees to change the By-laws to allow 18 of the 35 members to be voted by the alumni."

The initiative seems to be modeled on Dartmouth's 1891 agreement between Dartmouth College and its alumni to guarantee Dartmouth alumni the power to elect half of the Dartmouth board of trustees (discussed briefly here). The Dartmouth deal was struck during a period of immense financial hardship for the College which was plagued by poor management and other problems. The alumni decided to open their wallets to bail out the College financially, but insisted on having the power to elect half of the seats on the board in order to provide oversight to make sure their money wasn't squandered. My understanding is that in fact half of the members of the board stepped down immediately and their successors were elected by the alumni.

The Colgate group appears to be taking a related approach with respect to the financial aspect of the plan. They have set up an escrow fund to which alumni can donate contingent on the new proposal being adopted by the Colgate board. If the board does not adopt the proposal to permit alumni to elect half of the board by 2012, each donor's money will be released instead to a second beneficiary. In the meantime, the funds will be invested by Merrill Lynch.

One interesting aspect of the Colgate initiative is that those behind it are simply requesting procedural reforms to open up the trustee election process, rather than directly demanding certain substantive reforms, which has typically been the approach taken in the past by reformers.

Is anyone aware of any similar movements at other institutions to open up trustee selection processes?

Asylums and Prisons: Race, Sex, Age, and Profiling Future Dangerousness.

In Madness and Civilization, Michel Foucault documented a remarkable continuity of confinement through different stages of Western European history, from the lazar houses for lepers on the outskirts of Medieval cities, to the Ships of Fools navigating down rivers of Renaissance Europe, to the establishment in the seventeenth century of the Hôpital Général in Paris — an enormous house of confinement for the poor, the unemployed, the homeless, the vagabond, the criminal, and the insane.

“Leprosy disappeared,” Foucault writes, “the leper vanished, or almost, from memory; these structures remained. Often, in these same places, the formulas of exclusion would be repeated, strangely similar two or three centuries later. Poor vagabonds, criminals, and “deranged minds” would take the part played by the leper . . . . With an altogether new meaning and in a very different culture, the forms would remain—essentially that major form of a rigorous division which is social exclusion but spiritual reintegration.”

Social exclusion unites the asylum and the prison. The question that I ask in my research is whether we should think of the two populations as somehow linked. Is it possible that today’s category of the “criminally deviant” is tied to yesterday’s category of the “mentally defective”? In our social research, should we think of the two populations as a whole, rather than as two separate parts?

I am by no means suggesting that the same people have been moved from one institution (the asylum) to another (the prison). That is far too simplistic – for at least three important reasons.

Mental Illness: First, although the rate of mental illness among prison inmates is probably higher than among the general population and although the problems surrounding mental illness in jails and prisons have reached crisis proportions, it’s not the case that our prisons today are overwhelmingly housing persons with mental illness. For one thing, the war on drugs has taken an enormous toll on African-American communities, and has contributed to an unconscionable increase in black male incarceration that has nothing to do with mental illness. Bruce Western at Princeton documents this better than anyone in his new book, Punishment and Inequality in America.

Estimates of the number of mentally ill inmates vary. According to a 1999 report by the DOJ, about 283,800 inmates in prisons and jails suffered from mental illness at the time – which represented about 16% of jail and state prison inmates. A more recent 2006 DOJ study reported that 56% of inmates in state prisons and 64% of jail inmates across the country reported mental health problems within the past year. Steven Raphael at Berkeley has a fascinating paper and he finds that deinstitutionalization from 1971 to 1996 resulted in between 48,000 and 148,000 additional state prisoners in 1996, which according to him, accounted “for roughly 28 to 86 percent of prison inmates suffering from mental illness.”

A new paper by Steven Erickson and his colleagues reviews the literature on prison mental illness and shows that the estimates for mental illnesses, broadly defined, range from 16% to 90% and for severe mental illness from 6.4% to 39%. “These rates,” they suggest, “are well above those found in the general population of approximately 30% for mental illness and 6% for severe mental illness.” The paper is extremely skeptical of these estimates and casts doubt on the surveys based on methodological shortcomings.

For sure, it is exceptionally difficult to compare mental hospital residents of the 1950s to prison populations of the 1990s because the definitions, diagnoses, and medical routines have changed so much. Remember, the whole infrastructure of our mental health system has collapsed – making it unrealistic to measure the key attribute of “prior mental health contacts.” Moreover, drug use and psychotropic medications have changed enormously. But despite all that, the two populations must differ along somewhat-objective criteria of mental illness.

Race, Sex and Age: Second, the demographics of the two populations are different, as I discuss here in the Texas Law Review at pages 1781-1784. The prison population today is, overall, younger, much more male, and more African-American than the mental hospital populations at mid-century. In 1966, for example, there were 560,548 first-time admissions to mental hospitals, of which 310,810 (55.4%) were male and 249,738 (or 44.6%) were female. In contrast, new admittees to state and federal prison were consistently 95% male throughout the twentieth century. In 1978, African Americans represented 44% of newly admitted inmates in state prisons. That same year, minorities represented 31.7% of newly admitted patients in mental hospitals.

(But note that those populations were also changing internally. Henry Steadman and John Monahan report in a 1984 study that, in their sample, “the mean age at hospital admission decreased from 39.1 in 1968 to 33.3 by 1978. The percentage of whites among admitted patients also decreased, from 81.7% in 1968 to 68.3% in 1978.” There was a similar shift in the prison admissions data: “the mean age of prison admittees was 29.0 in 1968 and 28.1 in 1978" and the percentage of whites among prison admittees decreased from "from 57.6% in 1968 to 52.3% in 1978").

The War on Drugs: Third, a large portion of our current prison population consists of non-violent drug offenders. The war on drugs has helped fill our prison populations, especially our federal prisons. The following graph, from a forthcoming book with Frank Zimring at Berkeley on the Criminal Law and Regulation of Vice, traces the total sentenced population of the federal prison system and the number of federal prisoners for whom the most serious offense was a drug offense:

As I noted before, drug use may intersect in complicated ways with mental health issues, and some users may well be self-medicating. But the numbers associated with the war on drugs clearly transcend these possible connections.

As a result, the story is not simple trans-institutionalization. It is not simply substitution from one institution to another. But that does not mean that the populations are not sufficiently connected or similar in more important ways to be thought of as one – or counted as one. Could it be that we use the categories to socially exclude people we perceive as marginal, disorderly, abnormal? Do we use the categories to sift out those who offend our sensibilities and who we perceive as dangerous? Michel Foucault observed in Madness and Civilization that “There must have formed, silently and doubtless over the course of many years, a social sensibility, common to European culture, . . . that suddenly isolated the category destined to populate the places of confinement. To inhabit the reaches long since abandoned by the lepers, they chose a group that to our eyes is strangely mixed and confused. But what is for us merely an undifferentiated sensibility must have been, for those living in the classical age, a clearly articulated perception.”

Today, the categories of “mental illness” and “criminal deviance” seem very distinct. With the exception of those inmates who are diagnosed as suffering from mental illness, it seems wrong or confused to lump together the insane and the criminal, to mix the two categories. But is it? Will later generations question our own inability to see the continuity of social exclusion and confinement?

One place where the categories seem to be melding together is in the prediction instruments that we use to identify future dangerousness. We are now profiling the criminally dangerous, the mentally instable, and future sexual offenders in very similar ways. I trace the history of our profiling instruments in a new book, Against Prediction: Profiling, Policing, and Punishing in an Actuarial Age.

We’ve seen a rash of new actuarial instruments intended to predict future violent behavior. In terms of sexual violence, these include the Static-99, the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG), the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R), the Minnesota Sex Offender Screening Tool (MnSOST-R), the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide (SORAG), the Sexual Violence Risk-20 (SVR-20) and the HCR-20 — as well as, for the very first time, released in 2005, violence risk-assessment software, called the Classification of Violence Risk (COVR).

How accurate are these prediction instruments and how will they affect the profiled populations? John Monahan, a leading authority on prediction instruments, a proponent of these instruments (in fact co-author of the new COVR software), and the director of the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment project, offers a nuanced assessment. Writing in The Observer, Monahan asks: “How good are psychiatrists and psychologists at distinguishing which people with a mental illness will be violent? Research shows professionals are better than pure chance, but not much. Predicting harmful behaviour is like predicting bad weather. An inaccurate prediction doesn't necessarily mean the clinician or the meteorologist has 'missed something'; it may just mean the science of forecasting has a long way to go.”

Not much better than pure chance. Virginia just adopted a Sexually Violent Predators Act (“SVPA”) in April 2003 that provides for the civil commitment of sex offenders identified based on the Rapid Risk Assessment for Sex Offense Recidivism (RRASOR) – an actuarial instrument. The RRASOR consists of four items (prior sexual offenses, age at release, victim gender, and relationship to victim) and scores as a sum these four items. A score of 4 or more on the RRASOR (the higher scores) is associated with a 5-year sex offense recidivism rate of 37% and a 10-year sex offense recidivism rate of 55%.

Fifty-five percent — and remember, these are persons who have previously been convicted (rightly or wrongly) of a sexually violent offense. That leaves almost half the relevant population misidentified, at least for that 10-year span. Accuracy and inaccuracy may be in the eye of the beholder. (I discuss the reliability of other actuarial instruments in Against Prediction, reviewing studies like these here and here). The question is, how will these new actuarial methods and predictions of future dangerousness shape the people in our total institutions?

UPDATE MAY 4, 2007: John Monahan tells me that Virginia last year changed it's Sexually Violent Predators statute to require not the RRASOR but the Static-99. The Static-99 has slightly different cut-off scores depending on the age of the victim.

Related Posts (on one page): - Carceral Notebooks, Volume 2: Exploring the Carceral Zone with Nussbaum, Sunstein, Stone, Leitzel, McAdams, and Others.

- Concluding Thoughts on Total Institutions: Future Directions and Critical Reflections.

- Asylums and Prisons: Race, Sex, Age, and Profiling Future Dangerousness.

- Institutionalization vs. Imprisonment: Are There Massive Implications for Existing Research?

- Mental Hospital, Prison, and Homicide Rates: Some More Analyses.

- Mental Hospitalization and Prison Rates in Western Europe:

- On Mental Health Commitments and the Virginia Tech Shooting:

- Bernard Harcourt Guest-Blogging:

J.RR. Tolkien's Children of Hurin:

J.R.R. Tolkien's The Children of Hurin is now in print, and I just finished reading my recently arrived copy. Since Tolkien died in 1973, this book is actually a "reconstruction" by Tolkien's son Christopher Tolkien, working from his father's extensive unpublished notes and story fragments. I blogged about the debate over the "reconstruction" back in October, in this post. I think that the resulting book vindicates my prediction in the earlier that:

There is every reason to expect that Christopher Tolkien will do an equally good job of putting together The Children of Hurin [as he did with the earlier reconstruction of The Silmarillion], and that he will do his best to carry out his father's intentions.

The result will not be as good a book as might have emerged had J.R.R. Tolkien lived to finish it himself. But it will still reflect Tolkien's style and ideas, and will almost certainly be a lot better than nothing.

The book does indeed "reflect Tolkien's style and ideas." From just reading it, I would not have guessed that it was "reconstructed" as extensively as we know it has been. In many ways, the book is an expansion of the telling of the same story in the Silmarillion (where it is entitled "The Tale of Turin Turambar"). However, Children of Hurin broadens and deepens the tale and develops the characters better. To me, the most important difference is that the expanded version makes it much clearer that the hero suffers more from his own hubris and overly aggressive tactics than from bad luck or "fate." The story also emphasizes Tolkien's view (perhaps influenced by his experiences in World War I) that waging war against evil often requires time and patience, avoiding both premature defeatism and premature large-scale offensives.

The book is not without some shortcomings. But, overall, it is an impressive achievement by both J.R.R. and Christopher Tolkien. Anyone with any interest in Tolkien's work should definitely read it. And, no, the Tolkien family and their publishers didn't pay me to write that:).

The Post-Kelo Reform Debate Continued:

Bert Gall of the Institute for Justice has responded to my Reason Online article about Post-Kelo eminent domain reform. Bert's assessment of the state of eminent domain reform is more optimistic than mine.His piece is here. Most of the arguments he raises are similar to those he made in our earlier debate on this issue right here at the VC. For my take on his arguments, I refer you to my posts in that debate (see here and here; these posts also contain links to Bert's earlier posts).

Bert's Reason article does, however, contain two minor (and surely unintentional) misrepresentations of my argument. First, Bert claims that "Somin states that only 14 states have provided significantly increased protections for property rights." That is not correct. In fact, I wrote that only 14 state legislatures have enacted effective post-Kelo eminent domain reforms. Later on in my Reason article (as in my earlier writings on this issue), I emphasized that at least six states have enacted effective post-Kelo reforms by referendum. Four of them had not previously enacted effective reforms through the ordinary legislative process. Indeed, as I explain in greater detail in the paper on post-Kelo reform that kicked off this debate, the difference between citizen-initiated referenda and legislative efforts is a major part of my explanation for the pattern of reform that we have seen.

Second, Bert points to court decisions curtailing Kelo-like takings in several states, and implies that these refute my argument. However, my analysis specifically addresses only reforms enacted through the political process, and was in part meant to rebut claims that political reform would obviate the need for judicial intervention. I join Bert in applauding these decisions, and have in fact analyzed some of them in my own writings (e.g. - here).

But pointing to court decisions in no way refutes my arguments about legislative reform. Moreover, it is far from clear that these court decisions are the result of the Kelo backlash, since nine state supreme courts had forbidden economic development takings even before Kelo (two - Ohio and Oklahoma - have done so since then, and two or three others have limited takings in other ways). In sharp contrast to state legislatures (of which only one - Utah - acted before Kelo), several state supreme courts struck down economic development takings in the decade immediately proceeding Kelo. They include Montana (1995), Illinois (2002), South Carolina (2003), and Michigan (2004). For details, see my paper on the Michigan case, County of Wayne v. Hathcock. A complete listing of state cases is in Note 7 in this article.

Wednesday, May 2, 2007

A Brilliant Academic Presentation Using PowerPoint Slides:

The topic? Chicken. The Q&A at the end is particularly informative. (Hat tip: ZSM)

The New York Times on Zingerman's

an Ann Arbor institution that has to be the most overrated deli in the world. Not that it's bad. It just doesn't live up to its reputation, unless what you're looking for is a Midwestern translation of an upscale New York deli (which, if you're actually used to New York delis--unfortunately a dying breed--you almost certainly are not), with New York prices and beyond. Actually, some of its products, like bagels, are affirmatively bad, which would be forgiveable given the location if Zingerman's didn't have it's own bakery.

If you're in Ann Arbor and find yourself with a hankering for New York-style food, I recommend NYPD, a pizzeria with two locations. It doesn't compare with the best of Brooklyn, but it's way better than anything I've found in the entire D.C. metro area, so far.

Faculty Hiring Priorities at Colgate University:

Inside Higher Ed reports on Colgate's new approach to faculty hiring:

Which is more important — that a department have all of its disciplinary subfields represented or that it diversify its faculty? That’s the question being posed at Colgate University in an attempt to change how hiring committees have considered questions of diversity — and posing the question may be having an impact.

Lyle Roelofs, dean of the faculty, has been asking the question. Roelofs said that individual departments make the hiring decisions — “departments know how to judge quality” — but that as part of broad discussions about diversity at the university, he has tried to suggest some new ideas. Traditionally, he said that there has been a broad consensus (even if no formal policy exists) that the top factor to consider in a faculty hire is excellence in teaching and research, followed by match of candidates with the subfield specialties needed, then followed by diversity concerns.

After a series of efforts, Colgate has seen the percentage of minority faculty members rise to about 20 percent, with the percentage of women topping 40 percent. But as a small liberal arts university in a rural setting, Colgate has a hard time holding on to minority professors — and so needs to keep hiring them as well as trying to encourage more of them to make their careers at the university. Roelofs has asked departments to flop the second and third criteria. Excellence will stay on top, but diversity would generally trump subfield choice.

“There are going to be appropriate gains for us if we can be more diverse,” Roelofs said. “When you have a more diverse faculty, there emerges a greater diversity in curriculum. Greater value is placed on difference. So why not think about each hire and say, ‘in this situation are we better off thinking about how we need someone on 18th century reflection of Shakespeare, or have a broad description to maximize our opportunities on diversity?’ “

Civil unions pass in Oregon:

Two weeks after the state house did so, today the state senate voted to grant same-sex couples all of the rights, benefits, and responsibilities of married couples under state law. The governor has said he will sign the bill. As in the other states that have adopted civil unions, the new status is limited to same-sex couples and includes the age, consanguinity, capacity and other requirements to enter a marriage. Unlike marriage, there is no requirement of a solemnizing ceremony. The bill itself describes the status as a "binding civil union contract." Its text can be found here.

From the legislative findings:

(3) Many gay and lesbian Oregonians have formed lasting,

committed, caring and faithful relationships with individuals of

the same sex, despite long-standing social and economic

discrimination. These couples live together, participate in their

communities together and often raise children and care for family

members together, just as do couples who are married under Oregon

law. Without the ability to obtain some form of legal status for

their relationships, same-sex couples face numerous obstacles and

hardships in attempting to secure rights, benefits and

responsibilities for themselves and their children. Many of the

rights, benefits and responsibilities that the families of

married couples take for granted cannot be obtained in any way

other than through state recognition of committed same-sex

partnerships.

(4) This state has a strong interest in promoting stable and

lasting families, including the families of same-sex couples and

their children. All Oregon families should be provided with the

opportunity to obtain necessary legal protections and status and

the ability to achieve their fullest potential.

(5) Sections 1 to 9 of this 2007 Act are intended to better

align Oregon law with the values embodied in the Constitution and

public policy of this state, and to further the state's interest

in the promotion of stable and lasting families, by extending

benefits, protections and responsibilities to committed same-sex

partners and their children that are comparable to those provided

to married individuals and their children by the laws of this

state.

(6) The establishment of a civil union system will provide

legal recognition to same-sex relationships, thereby ensuring

more equal treatment of gays and lesbians and their families

under Oregon law.

Oregon joins California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Vermont in extending all of the benefits and responsibilities of marriage to same-sex couples. Hawaii, Maine, Washington state, and D.C, grant legal recognition and some of the rights of marriage to same-sex couples. That makes ten states (plus DC) recognizing and protecting gay families to some extent. Seven of these have done so legislatively; the other three under court compulsion.

Oregon is different in one important respect from the other states that have so far adopted civil unions. Unlike the other civil-union states, there's a possible legal challenge to the new law in Oregon: the state passed a constitutional amendment in 2004 limiting marriage to one man and one woman. While the new law does not let gay couples marry, opponents can be expected to argue that granting the substance of marriage to gay couples without the name nevertheless violates the state constitution. However, a difference between the Oregon constitutional amendment and many other state marriage amendments is that it did not ban marriage and "the equivalent of marriage" for same-sex couples. It was thus a narrower amendment than the ones that have passed elsewhere. Whether that sort of difference will save the new civil union law in Oregon state courts remains to be seen.

Wisconsin Right to Life vs. FEC

This is the case, recently heard by the Supreme Court, that may place some First Amendment limits on McCain-Feingold's speech-suppression laws. The amicus brief in which the Independence Institute participated is here. A collection of other briefs and documents is here. It is a good test case because the advertisement in question (urging Wisconsin citizens to tell Senator Feingold stop supporting the filibusters of Bush-nominated judges) was plainly a communication about the business of Congress, rather than a thinly-disguised campaign advertisement (e.g., "Tell Senator Snort that you're upset that he was arrested for domestic violence 10 years ago.") Yet the advertisement was claimed to be illegal by the FEC because it was aired within 60 days of the general election.

"Lawful Incest May Be on the Way" -- But It's Already Here!

Jeff Jacoby reports on calls in Germany for decriminalizing adult brother-sister incest. "Parts of Europe are already heading down this road. In Germany, the Green Party is openly supporting the Stubings in their bid to decriminalize incest. 'We must abolish a law that originated last century and today is useless,' party spokesman Jerzy Montag says. Incest is no longer a criminal offense in Belgium, Holland, and France. According to the BBC, Sweden even permits half-siblings to marry." He closes:

Your reaction to the prospect of lawful incest may be "Ugh, gross." But personal repugnance is no replacement for moral standards. For more than 3,000 years, a code of conduct stretching back to Sinai has kept incest unconditionally beyond the pale. If sexual morality is jettisoned as a legitimate basis for legislation, personal opinion and cultural fashion are all that will remain. "Should Incest Be Legal?" Time asks. Over time, expect more and more people to answer yes.

We've blogged about incest and the law before; in particular, I've discussed adult stepparent-stepchild incest, and it seems to me there are comparable arguments for continuing to ban adult sibling incest. I don't want to suggest that bans on adult incest are categorically improper, or that they're proper. But I do want to raise one interesting item related to the "code of conduct stretching back to Sinai" -- it turns out that this code doesn't ban uncle-niece incest.

What's more, at least one state (Rhode Island) exempts Jews from its ban on uncle-niece incest, including the ban on uncle-niece marriages. (given modern religious equality jurisprudence, I take it that this would be extended to anyone whose religious beliefs mirror orthodox Jewish beliefs on the subject). Colorado and Minnesota likewise follow the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act in exempting uncle-niece marriages that are "permitted by the established customs of aboriginal cultures." Some states therefore not only fail to criminalize all such marriages, but will actually legally recognize them. At least one state, Oregon, doesn't criminalize uncle-niece sex at all (O.R.S. § 163.525) but doesn't recognize such marriages (O.R.S. § 106.020).

Now maybe this is just a historical oddity; my sense is that very few women want to marry their uncles. But my sense is also that very few siblings want to marry each other. So the questions for those who rest on the importance of 3000-year traditions remain: Should we be as respectful of this tradition when it allows adult uncle-niece sex, but bars adult sibling-sibling sex (including among siblings who were raised separately, which I believe is what had happened in the German case Jacoby mentioned)? Should we stick with the tradition, and allow uncle-niece marriages while barring sibling-sibling marriages? Or should we focus less on the 3000-year-old tradition, and more on what seems sensible now?

Escheating Scandal:

OK, this Ninth Circuit case is not terribly exciting legally, but it's practically useful, and it lets me say "escheating scandal." (No google references for that until now; a poor gag, but mine own.) An excerpt from an earlier, more detailed decision in this litigation:

[The case is filed] by two individuals against the state controller. One,

Chris Taylor, a former Intel employee, lives in England and

owns 52,224 shares of Intel stock. The other, Nancy Pepple-

Gonsalves, a former TWA flight attendant, lives in California,

in Riverside County, and owns 7,000 shares of TWA stock. Or at least they did own the stock, before the state took it

away.

The state controller took Mr. Taylor’s and Ms. Pepple-

Gonsalves’s stock as “unclaimed property.” But these individuals

do, in this lawsuit, claim it. The property was treated as

unclaimed because for three years these two individuals did

not cash dividend checks, respond to proxy notices, or otherwise

communicate to the companies in which they owned stock.

Intel and TWA provided the State of California with lists of