|

Saturday, February 2, 2008

ABA to Set New Bar Passage Standards for Accreditation:

National Law Journal

In general, the change would create a quantitative rule requiring law schools to demonstrate that 75% of their graduates passed the bar exam or to show that their pass rates were within a certain range compared with other law schools in the same jurisdiction. The change is technically a new interpretation of an existing accreditation standard. Almost all states require law students to graduate from an ABA-accredited law school in order to obtain a license to practice.... At a hearing last month before the Accreditation Standards Review Committee about the change, several prominent lawyers and scholars expressed their disapproval. Among them was General Motors North America Vice President and General Counsel E. Christopher Johnson, who argued that a bright-line rule would hurt minority enrollment because it would deter law schools from accepting applicants with lower scores on the Law School Admission Test.

Johnson is probably right, though another possibility is that pressure would come to bear on state bars to make their bar exams easier (which, as someone who doesn't believe in bar exams to begin with, I think would be a good thing). Meanwhile, one can question whether schools whose minority students pass the bar at rates well below 75% are doing those students much of a favor by accepting them despite low LSAT scores that predict future bar passage issues, taking their tuition money, and then leaving half or more of them without a career as an attorney.

Thanks to Paul Caron at TaxProf for the pointer.

Spell-Checking "Obama" into "Osama":

Benjamin Zimmer (Language Log) reports on this, and a quick experiment confirmed it. (Of course, as ABC News points out, it's not that someone at Microsoft is somehow deliberately anti-Obama; it's just that Obama wasn't in the dictionary -- that makes sense -- but Osama was, so the spell-checker suggested it.)

As the ABC story puts it, "When Fast Isn't Fast Enough, Spell-Checker Isn't Always Your Friend."

Political Ignorance and Belief in Conspiracy Theory:

Cass Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule have posted an excellent new paper on belief in conspiracy theory. As they point out, belief in highly dubious conspiracy theories about key political events is widespread. For example, they cite survey data showing that some one third of Americans believe that federal government officials either carried out the 9/11 attacks themselves or deliberately allowed them to happen. Large numbers of people also believe that John F. Kennedy's assassination was the result of a wideranging conspiracy in the government, that the AIDS virus was secretly produced in a government laboratory for the purpose of infecting blacks, and that the government is covering up evidence of alien visitation of Earth.

Why are such irrational beliefs so widespread in an open society where information refuting them is easily accessible? Sunstein and Vermeule present some possible answers. But they fail to consider a crucial question: Why is belief in bogus political conspiracies so much more widespread than comparably irrational beliefs about conspiracies in our daily lives? Far more people believe that the CIA killed Kennedy or engineered the 9/11 attacks than believe that a dark conspiracy is out to get them personally or that their associates and co-workers are plotting against them. Millions of people who embrace absurd conspiracy theories about political events are generally rational in their everyday lives.

In my view, the disjunction has to do with the rationality of political ignorance. As I describe in more detail in several of my works (e.g. - here and here), it is perfectly rational for most people to know very little about politics and public policy - and indeed most people are quite ignorant about even basic aspects of these subjects. Because the chance of your vote influencing the outcome of an election is infinitesmally small, there is little payoff to becoming informed about politics if your only reason for doing so is to be a better voter. By contrast, there are very strong incentives to be well-informed about issues in our personal and professional lives, where our choices are likely to be individually decisive. The person who (falsely) believes that a dark conspiracy is out to get him will impose tremendous costs on himself if he bases his decisions on that assumption; he's likely to end up a paranoid recluse like Bobby Fischer (who, of course, embraced political conspiracy theories as well).

In the political realm, on the other hand, widespread rational ignorance helps to spread conspiracy theory in two ways. First, the more ignorant you are about politics and economics, the more plausible simple conspiracy theory explanations of events are likely to seem. If you don't understand basic economics, you are more likely to believe that rising oil prices are caused by a conspiracy among oil companies or that the subprime crisis was caused by a conspiracy among banks. If you don't understand the basic workings of our political system, you are more likely to swallow the idea that the federal government could carry out something like the 9/11 attack and then (falsely) blame it on Osama Bin Laden without the truth being quickly exposed through leaks and hostile media coverage.

Second, the rationality of political ignorance implies that even people who do have considerable knowledge are likely to be more susceptible to conspiracy theories about political events than in their personal lives. As I explain in this paper (see also Bryan Caplan's excellent book), the rationality of political ignorance not only reduces people's incentives to acquire political information, it also undercuts incentives to rationally evaluate the information they do learn. As a result, we are more likely to be highly biased in the way we evaluate political information than information about most other subjects. Many people embrace political conspiracy theories because they are more entertaining and emotionally satisfying than alternative, more prosaic explanations of events. Unlike in our nonpolitical lives, most people have little incentive to critically evaluate their political beliefs in order to weed out biases and and ensure their truth.

That is not to say that people are uniformly rational in their nonpolitical decisions. Far from it. But they are likely to be a great deal less irrational than they are about politics.

Obama vs. Hillary on Subprime Mortgages:

There was an interesting exchange on subprime mortgages between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton during their last debate. Hillary argued for a mortgage freeze (hat tip: Instapundit):

I think it’s imperative that we approach this mortgage crisis with the seriousness that it is presenting. There are 95,000 homes in foreclosure in California right now. I want a moratorium on foreclosures for 90 days so we can try to work out keeping people in their homes instead of having them lose their homes, and I want to freeze interest rates for five years.

Obama pointed out a serious flaw in her proposal:

On the mortgage crisis, again, we both believe that this is a critical problem. It’s a huge problem in California and all across the country. And we agree that we have to keep people in their homes.

I have put forward a $10 billion home foreclosure prevention fund that would help to bridge the lender and the borrower so that people can stay in their homes.

I have not signed on to the notion of an interest rates freeze, and the reason is not because we need to protect the banks. The problem is, is that if we have such a freeze, mortgage interest rates will go up across the board and you will have a lot of people who are currently trying to get mortgages who will actually have more of a difficult time.

Obama is right to point out that Hillary's proposed mortgage freeze would create perverse incentives. But his own proposal for a bailout has a similar weakness. If the government bails out subprime borrowers and lenders who made bad decisions, that will create incentives for future borrowers and lenders to take unjustified risks of their own. The end result will be a serious moral hazard that leads to overinvestment in overvalued real estate - drawing funds away from potentially more productive uses elsewhere. Both borrowers and lenders will expect the government to bail them out if future risky morgages go into default.

In addition, as I emphasize in this post, a bailout would impose large costs on innocent third parties: the taxpayers. If we genuinely want to prevent unwise mortgage borrowing while simultaneously protecting the interests of future homebuyers and innocent third parties, the right strategy may well be for government to do little or nothing. If both lenders and borrowers have to pay the price for their mistakes, they will be less likely to repeat them.

Enzyte a Fraud -- Who Knew?!

The Cincinnati Enquirer reports that a former executive for the company that sold the Enzyte "male enhancement" pill admitted in court that the company's claims were completely made up.

James Teegarden Jr., the former vice president of operations at Berkeley Premium Nutraceuticals, explained Tuesday in U.S. District Court how he and others at the company made up much of the content that appeared in Enzyte ads.

He said employees of the Forest Park company created fictitious doctors to endorse the pills, fabricated a customer satisfaction survey and made up numbers to back up claims about Enzyte’s effectiveness.

“So all this is a fiction?” Judge S. Arthur Spiegel asked about some of the claims.

“That’s correct, your honor,” Teegarden said.

Teegarden’s testimony is key to the case federal prosecutors are making against Berkeley and its founder, Steve Warshak, who is accused of orchestrating a $100 million conspiracy to defraud thousands of customers.

Warshak faces up to 20 years in prison and millions of dollars in penalties if his trial ends with a conviction.

AOL - Time Warner to merge!

Oh wait, I mean Microsoft and Yahoo! ... which does smell, to me, a lot like the AOL-Time catastrophe of just a few years past. The aging giant of days of yore (that would be Microsoft) looking for a way to get hip (that would be Yahoo!) and BIG in a hurry. But (you heard it here first) it will end in tears. Dust off those stories about how the two cultures don't merge, and about how the "expected synergies" never seemed to materialize. You have to be big to beat google at its game, but you can't buy your way big. I'm gonna short this deal, for sure.

Reinventing "24":

Today's WSJ has an interesting story about Fox's effort to reinvent -- and reinvigorate -- its hit series, "24".

Against the real-life backdrop of global terrorist attacks, "24" at its peak fulfilled the fantasies of an insecure nation. It became one of the most important franchises for News Corp.'s Fox Broadcasting Co., with 17 million viewers tuning in some weeks and millions returning to watch on DVD. . . .

But those who ride the tide of the times can also get upended by them. As public opinion about the Iraq War turned south, the show's depiction of torture came to be seen as glorifying the practice in the wake of real-world reports of waterboarding and other interrogation techniques used on detainees.

Ratings dropped by a third over the course of last year's sixth season. Producers would later experience trouble casting roles, once some of the most desirable in television, because the actors disapproved of the show's depiction of torture. "The fear and wish-fulfillment the show represented after 9/11 ended up boomeranging against us," says the show's head writer, Howard Gordon. "We were suddenly facing a blowback from current events."

Last spring, Fox executives asked producers to come up with a plan for what to do with their onetime crown jewel. The producers decided to take the radical -- and rarely attempted -- step of reinventing the show. While some fans complained "24" had grown too formulaic, the producers also grudgingly saw the importance of wrestling the show from its ties to an unpopular conflict.

The result: "24" is nowhere to be found on the TV schedule. For weeks the show's producers tried to reconcile the show's premise with the new public mood. Should Jack atone for his sins? Is Jack bad? The script rewrites and philosophical crises left the show so far behind schedule that when the Hollywood writers went on strike in November, Fox had no choice but to delay its premiere date. The show could premiere this summer, next fall or as late as January 2009.

Climate Change, Cumulative Evidence, and Ideology:

Almost every time I post something on climate change policy, the comment thread quickly devolves into a debate over the existence of antrhopogenic global warming at all. (See, for instance, this post on "conservative" approaches to climate change policy.) I have largely refused to engage in these discussions because I find them quite unproductive. The same arguments are repeated ad nauseum, and no one is convinced (if anyone even listens to what the other side is saying). I have also seen nothing in these exchanges that would alter my current assessment of the scientific evidence.

Given my strong libertarian leanings, it would certainly be ideologically convenient if the evidence for a human contribution to climate change were less strong. Alas, I believe the preponderance of evidence strongly supports the claim that anthropogenic emissions are having an effect on the global climate, and that effect will increase as greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere. While I reject most apocalyptic scenarios as unfounded or unduly speculative, I am convinced that the human contribution to climate change will cause or exacerbate significant problems in at least some parts of the world. For instance, even a relatively modest warming over the coming decades is very likely to have a meaningful effect on the timing and distribution of precipitation and evaporation rates, which will, in turn, have a substantial impact on freshwater supplies. That we do not know with any precision the when, where, and how much does not change the fact that we are quite certain that such changes will occur.

So-called climate "skeptics" make many valid points about the weakness or unreliability of many individual arguments and studies on climate. They also point out how policy advocates routinely exaggerate the implications of various studies or the likely consequences of even the most robust climate predictions. Economists and others have also done important work questioning whether climate risks justify extreme mitigation measures. But none of this changes the fact that the cumulative evidence for a human contribution to present and future climate changes, when taken as a whole, is quite strong. In this regard, I think it is worth quoting something Ilya wrote below about the nature of evidence in his post about 12 Angry Men": People often dismiss individual arguments and evidence against their preferred position without considering the cumulative weight of the other side's points. It's a very easy fallacy to fall into. But the beginning of wisdom is to at least be aware of the problem. The "divide and conquer" strategy of dissecting each piece of evidence independently can make for effective advocacy, but it is not a good way to find the truth.

Don't get me wrong. I believe that there is room to question the global warming "consensus," particularly as represented by activist groups and some in the media, and to challenge various climate scenarios and their policy implications. I am unpersuaded that climate change threatens civilization or justifies truly draconian measures. Nevertheless, I believe climate change is a serious concern. And as much as I wish it were not the case, I believe the threat of climate change justifies some measures that the libertarian in me does not much like. But that's the way it is.

Predictocracy vs. Futarchy:

In describing normative markets in my book, I outline the possibility of prediction market-based legislative, judicial, and even executive power, but only for heuristic value. Nonetheless, it is fun to indulge in political science fiction and imagine a government run by prediction markets. I hope that this exercise can convince people that prediction markets are a powerful and flexible tool that may be useful in more modest but still exciting ways.

A predictocracy, then, is a government in which normative markets make the full range of government decisions, except when the prediction market mechanism results in a decision to delegate a decision to some other mechanism (whether traditional or using prediction markets in some other way).

I am not the first to imagine prediction markets serving at the center of government. Robin Hanson has previously defended a form of government that he calls "futarchy." His vision is that the legislature would be limited to defining some objective function (a GDP+ that includes GDP, but also anything else of value). Only policies that conditional markets predict would increase GDP+ would be enacted.

The slight disagreement between Hanson and me may sound to skeptics and even many prediction market enthusiasts like an argument between religious fanatics who have already disengaged from reality. But in Predictocracy, I explain why I prefer predictocracy to futarchy, and Hanson has now respectfully joined the argument.

My principal reasons for preferring predictocracy stem from the caveats that I previously offered about conditional markets. I worry that there will be too much noise in estimating GDP+ to make reliance on the difference between two conditional markets reliable (except for monumentally large decisions), and also that any prediction market subsidies in futarchy won't be well targeted.

Hanson points out that futarchy could authorize predictocracy-like decision making for particular decisions, and vice versa, and so he argues that we should pick the system that would make better decisions on the largest issues. But I worry that the caveats about conditional markets suggest that futarchy might not be the best vehicle for determining whether predictocracy should be used for particular realms of decision making. It would work only if large enough realms were being carved out to make a meaningful impact on GDP+.

Hanson makes some strong points in favor of futarchy. "Democracy today suffers from enormous errors regarding estimates of policy consequences, i.e., of passing particular bills," he points out. Predictocracy reduces the effects of the errors, since evaluations can be made years after a policy is enacted, but ex post evaluators in predictocracy might make some systematic errors that prediction market traders in futarchy would fix.

Futarchy, however, introduces another type of error, the danger that the legislature will not do a good job of defining GDP+, as Hanson acknowledges. It's not a priori clear which would be worse -- errors by the legislature in developing a formula for GDP+, or errors by ex post evaluators in determining whether a particular policy has increased or decreased general welfare. It probably depends to some extent on the quality of our legislature and the quality of our average ex post judges.

Ultimately, the question reduces to this: Suppose all you knew about a policy was that (a) one prediction market forecast that it would increase a measure of GDP+ devised by the legislature; and (b) another prediction market forecast that people some years later would conclude that this policy was a bad idea.

I would tentatively suppose that the participants in market (b) recognized some limitation of GDP+ that would be apparent after enactment of the policy. Robin would guess that the participants in market (b) anticipated that the ex post evaluators would fail to identify some actual policy consequence of the policy.

Given my views on this question, and the challenges of using futarchy for relatively small decisions, I would prefer predictocracy. Most readers who have followed the argument so far probably prefer traditional forms of republican government -- and I do too, because of transition problems and uncertaintty.

Ultimately, I believe that both markets forecasting particular consequences of potential government decisions and normative markets forecasting ex post assessments of policies could be useful tools within traditional republican governance.

Friday, February 1, 2008

12AM:

It's not just the time, it's also the movie Ilya and David blog about below (and one of my favorites). Ilya considers whether the defendant in 12 Angry Men was really guilty. I think the author, Reginald Rose, deliberately leaves that unclear. The audience never even hears any testimony, and what we hear second-hand from the jurors is conflicting. It's conflicting for a reason, I think; the idea is to make the audience dwell on the difference between guilt and the absence of reasonable doubt of guilt. David suggests that Henry Fonda asks a lot of questions that should have been asked by the defense attorney. I would put this a bit differently: I think Henry Fonda is the defense attorney. Rose's clever move is to take a criminal case -- government witnesses, followed by cross examination, closing, and then jury deliberations -- and to present them all as all just part of the jury deliberations. As I see it, the jurors who think the case is easy present the government's case; Fonda's questions are the cross examination and closing argument; and the hostile reaction by jurors who object to Fonda's inquiries are the testimony of the goverment's witnesses under cross examination. This device lets Rose tell the story of an entire criminal trial under the guise of the screenplay being just about jury deliberations. Great stuff.

Goldstein v. Pataki and the Shortcomings of Kelo:

The US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit recently decided Goldstein v. Pataki, a case challenging the condemnation of homes and other property in Brooklyn for the purpose of transferring them to developer Bruce Ratner, owner of the New Jersey Nets. Ratner plans to use the land to build a new stadium for the Nets, as well as other facilities, including some 2250 new housing units.

Not surprisingly, the Second Circuit upheld the condemnations. Under Kelo v. City of New London, they had very little choice. As I discuss in great detail in this article, Kelo mandates very broad judicial deference to the government in determining whether a condemnation is a genuine "public use" under the Fifth Amendment. Any potential benefit to the general public is sufficient, even if it is greatly outweighed by the project's cost.

The case nonetheless reveals some of the serious shortcomings of Kelo and related precedents. Goldstein v. Pataki is a correct application of Kelo; it is also an example of the sort of abuse that more robust judicial protection of property rights could prevent.

First, the fact that much of the condemned land is to be used to build a sports stadium raises serious red flags about the true likelihood that the general public will benefit from the condemnation. Numerous studies by economists show that public subsidies for stadium construction create no economic benefits for the general public (see, e.g, this book published by the liberal Brookings Institution).

Second, the court claims that the creation of "affordable housing" for the poor is one of the public benefits to be expected from the project. The project will indeed create some new housing units (in addition to the stadium). However, as the Second Circuit opinion concedes (pg. 15), almost 70% of the new housing units will be "luxury" units for the wealthy, and the remainder is mostly not guaranteed to be ever built and is still intended for the "middle class" rather than the poor. Like the stadium, the housing portion of the project seems likely to be a straight redistribution of wealth from the current residents of the area to the very wealthy Mr. Ratner and the types of wealthy people who will be able to afford to buy the luxury housing he intends to build. To say the least, it is hard to discern any genuine public benefit here.

The Second Circuit also justifies the takings on the basis that they will serve to alleviate "blight." New York City has indeed designated much of the area condemned area as blighted. However, the validity of this designation is debatable at best (the plaintiffs pointed out that much of the land in the area is among the most valuable in Brooklyn). As I discuss in this article, New York is one of many states with a definition of "blight" so broad that it can encompass virtually any property. Even if the area really is "blighted," it doesn't necessarily follow that the current owners and residents should be expelled and their land transferred to a politically powerful developer. Cities have many other options for alleviating genuine blight that do not infringe so greatly on property rights. At the very least, there is no good reason to condemn the 50% of the project area that even the city acknowledges to be free of blight (see pg. 14).

In this case, as in Kelo itself, the court took account of the claimed benefits to the general public, but explicitly refused to consider the massive costs (pp. 13-15). Ignoring cost is a requirement under Kelo. But it is not a good way of determining whether a planned condemnation is actually likely to serve a "public use" - even if "public use" is defined broadly to include indirect public "benefits." Like those in Kelo, the Goldstein takings seem highly likely to create more costs than benefits for the general public. Ignoring costs is a blank check for local governments to undertake condemnations that benefit politically powerful interests while imposing the costs on taxpayers and the politically weak.

Finally, the Second Circuit notes that "Ratner was the impetus behind the [condemnation] Project, i.e., that he, not a state agency, first conceived of developing Atlantic Yards, that the Ratner Group proposed the geographic boundaries of the Project, and that it was his plan for the Project that the ESDC [government agency undertaking the condemnations] eventually adopted without significant modification." The court is probably right to conclude that this is not enough to prove that the taking was a "pretextual" one under Kelo. At the very least, however, such a pattern of events should trigger heightened judicial scrutiny of the government's true purposes in undertaking the condemnation. The fact that this kind of special interest-driven project receives only the most cursory possible judicial scrutiny is one of Kelo's many shortcomings.

Twelve Angry Men and the Cumulative Weight of Evidence:

Twelve Angry Men, the classic movie discussed in David's post was a great film. But I've always thought that the defendant Henry Fonda's character persuades the jury to acquit was actually guilty. There were four or five separate pieces of evidence pointing to the defendant's guilt, including two separate eyewitnesses. Fonda's character does a good job of showing that no one piece of evidence was enough to prove the accused guilty beyond a reasonable doubt by itself. But he and the other jurors ignore the possibility that guilt might be established by the cumulative weight of multiple pieces of evidence that are individually insufficient. For example, let's assume that the defendant has five pieces of evidence against him and each of them individually shows that there is only a 70% chance of his being guilty. The combined probability of his guilt based on all five items is about 99.8%, more than enough to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. By focusing on each piece of evidence individually, Fonda's character obscures this fact and persuades the jury to let a guilty man go. Obviously, this interpretation of the movie is not the one that the filmmakers wanted the audience to come away with. But I think it fits the evidence nonetheless.

In real life, this "divide and conquer" strategy was effectively used by O.J. Simpson's defense lawyers, who raised doubts about some of the individual items of evidence against their client, but successfully avoided confronting the fact that he was almost certainly guilty based on the cumulative weight of many different items of evidence. Former prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi discusses this in his excellent book on the Simpson case.

The point is applicable to issues beyond criminal law. People often dismiss individual arguments and evidence against their preferred position without considering the cumulative weight of the other side's points. It's a very easy fallacy to fall into. But the beginning of wisdom is to at least be aware of the problem.

UPDATE: My analysis assumes that the five pieces of evidence were conditionally independent of each other (i.e. - that the discrediting of one does not affect the odds of the others being valid). That, I think, is an accurate representation of the evidence in the movie, which consistent of several independent items: two separate eyewitness accounts, some items of physical evidence, and flaws in the defendant's alibi. Related Posts (on one page): - 12AM:

- Twelve Angry Men and the Cumulative Weight of Evidence:

- A Debate on "Twelve Angry Men":

Massachusetts Trial Court Decision Rejecting Wiretapping / Disturbing the Peace Charges

against Simon Glik, who recorded a police arrest, is here; thanks to Harvey Silverglate for the pointer. Related Posts (on one page): - Massachusetts Trial Court Decision Rejecting Wiretapping / Disturbing the Peace Charges

- The Dark Side of "Privacy Protections," Continued:

A Debate on "Twelve Angry Men":

Via Overlawyered, you can find a harsh critique of the classic jury deliberation movie here, and a vigorous defense here.

I saw the movie many years ago, but I remember that my reaction was that Henry Fonda raised many questions that should have been asked by the defense lawyer (e.g., maybe an eyewitness wasn't wearing her eyeglasses), raising two possibilities: (1) that the defense lawyer was incompetent; or (2) that the defense lawyer knew that the answers wouldn't have helped his client. This raised, to me, a broader issue: to meet his burden of proof, does a prosecutor need to anticipate and rebut all possible objections, even those not actually raised by the defense attorney, or is it enough for the jury to determine that if one accepts the evidence placed before them by the two sides, the prosecutor has the overwhelmingly stronger case?

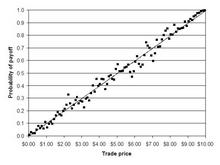

Correlation Between Grades and Essay Answer Length:

Last semester, I for the first time recorded in my exam scoring spreadsheet the length of each answer. This let me figure out the correlation between the length and the grade.

Note that my exam had 13 multiple choice questions (which amounted to 1/3 of the grade) and one long essay (which amounted to 2/3 of the grade, and for which the median answer was about 3750 words). The students had four hours to do the exam, and the exam was open book and open notes.

The correlation coefficient of the total score (which combined the essay score and the multiple choice score) and the essay word count was 0.60, which is huge as correlations go. So longer is better, by a lot, right? The correlation between the total score and the word count for exams longer than the median exam was basically zero.

In fact, I sorted the spreadsheet by word count, and then added a column for each exam that measured the correlation between total score and essay word count for all exams this exam and longer (the Excel formula for the 5th shortest exam of the 81 total, for instance, was =CORREL(B5:B$81,K5:K$81), where column B was the total score and column K was the essay length). The column started at 0.60, got steadily smaller until the median, and then immediately past the median exam the column fell to basically 0 (-0.01, to be precise) and pretty much stayed that way as the exams got longer.

I also did the same with the correlation between the essay score and the word count. For that, the inflection point didn't appear until exam 50 out of 81, rather than 42 out of 81. That makes sense: Time spent on the essay is time not spent on the multiple choice, so there's some tendency for the longer essays (past a certain length) to have slightly smaller multiple choice scores.

Likewise, the correlation between essay word length and multiple choice score was mildly positive if we looked at all exams (0.12), but fell to basically 0 once one set aside the 17 shortest exams -- and once one set aside the 35 shortest exams, the correlation between essay word length and multiple choice score got to be -0.10 and stayed pretty much there (with some fluctuations).

Is this of any use to students? I highly doubt it -- it's hard to act on the advice, "write at least as many words as your median classmate," and in any event simply trying to make your exam longer is unlikely to make it better (even if longer is usually better, up to a point). Still, it struck me as an interesting data point; and perhaps some students might be happy to know that, past a certain level, quantity and quality aren't even correlated.

In any case, this is just one set of data; in past years, I didn't include the word counts in my spreadsheets, so I couldn't do the same analysis. But I'd love to see what other law professors find.

American Muslims' Demands for Religious Exemptions:

My post on the Muslim soldier's religious exemption demand reminded me of a point I made several months ago:

Recent years have seen a set of requests by Muslims for exemptions from generally applicable laws and work rules. A Muslim policewoman in Philadelphia, for instance, asked for an exemption from police-uniform rules so that she could wear a Muslim headdress. A few years ago, a Muslim woman in Florida asked that she be allowed to wear a veil in a driver’s license photo. Last year, a Muslim woman in Michigan asked that she be allowed to testify veiled in a small-claims case that she brought.

All these claims were rejected by courts, and likely correctly, though the arguments for the rejection are not open-and-shut. But some of the public reaction I’ve seen to the claims suggests that people are seeing such claims as some sort of special demands by Muslims for special treatment beyond what is given Christians, Jews, and others. And that turns out not to be quite so: While the claims are for religious exemptions for Muslims, they are brought under general religious-exemption statutes that were designed for all religions and that have historically benefited mostly Christians (since there are so many Christians in America).

The Muslim exemption claims are plausible attempts to invoke established American religious-exemption law, and they deserve to be treated as such -- even if there are good reasons for rejecting them, as American religious-exemption law recognizes. Let us briefly review this law, so that this becomes clearer.... [Go here to keep reading.]

This is an excellent example. People of many religious groups have demanded exemptions from military service. In some measure, American law has chosen to expressly accommodate them, for instance through the conscientious objector exemption for people who oppose all wars (which especially benefits Quakers and other pacifist groups). Some members of other religious groups have also demanded exemptions, for instance when they believed that as Catholics they had a religious obligation not to fight in wars they believed to be unjust. Their claims were considered and rejected, using the then-standard constitutional approach for considering religious exemption demands (which has now been reinstated as a federal statutory approach).

The Muslims are just the latest group to do so. Their objections may be somewhat different from the Catholics', in that to some Muslims they may turn on the religious identity of the people on the other side. But other Muslims' objections appear to be very similar to some more familiar religious objections; for instance, in the case I discuss below, one of the quoted Muslim scholarly opinions suggested a just/unjust war distinction that in principle sounds much like the rule asserted by the Catholic objector in Gillette v. U.S.. And more broadly, Muslims are simply taking advantage of a longstanding American tradition -- the tradition of often (though not always) accommodating people's religious objections to generally applicable laws.

Sometimes the Muslim objector's demands should be rejected and sometimes they should be accepted. But they shouldn't be seen as some striking innovation brought here by some foreign interlopers. One commenter to an earlier post about accommodation of Muslim female athletes complained that, when Muslims "come here, we're expected to conform to their rules, not the other way around." Yet that misses the point: One of our rules, which we've followed for centuries, is precisely that sincere religious objections -- whether brought by familiar religions or recently imported ones -- should often (not always, but often) be accommodated.

Muslim Soldier's Religiously Motivated Refusal to Deploy to Iraq:

The Army Court of Criminal Appeals just handed down an opinion on this a few days ago, rejecting the claim, asserted by Sgt. Abdullah Webster as a defense to charges of "missing movement by design and disobeying a superior commissioned officer." A few highlights:

1. "Appellate defense counsel now assert the military judge erred in accepting

appellant's plea because he 'did not freely plead guilty' and appellant's 'guilty plea

was irregular and not freely given because the Islamic scholars ... forbade [defendant] from deploying to Iraq [and] doing so would condemn [appellant] to hell." The court says no: "It is irrelevant that appellant missed movement or failed to obey the orders of

his superior commissioned officers based on religious motives."

2. Defendant also argues that the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act provides a defense, presumably because of his view that

Based upon the advice given to me by Islamic Scholars ... the conclusions were: 1. Consensus was that this [sic] no Muslims are permitted. 2. Muslims are not allowed to kill another Muslim except under three conditions . . . . Given the religious ruling, any combatant role I undertake would jeopardize my belief and place me in an unfavorable position on the Day of Judgment.

RFRA provides that, when the federal government substantially burdens a person's religious practice -- for instance, by requiring him to do something that his religion forbids -- the person is entitled to an exemption (even when the law is generally applicable, and doesn't single out religious people for special burden) unless the government shows that applying the law to the person is the least restrictive means to serve a compelling government interest.

The court says no: Even if the order burdened defendant's religious practice (which the court assumes for the sake of argument),

The Army has a compelling interest in requiring soldiers to deploy with their units. As the Supreme Court has said, “[i]t is ‘obvious and unarguable’ that no governmental interest is more compelling than the security of the Nation.” The Army’s primary mission is to maintain national security by fighting and winning our nation’s wars. The Army cannot accomplish this primary mission if it cannot deploy, in a state of military readiness, the various units into which it is organized. Giving soldiers the option to decide selectively whether they wish to participate in particular military operations would undermine the readiness of all units to deploy, and thus compromise the Army’s mission and national security.

In this case, the Army furthered its compelling interest in the least restrictive manner possible. Although the Army required appellant to deploy with his unit, the Army made numerous allowances for him. The Army afforded him the opportunity to request relief as a conscientious objector. The Army gave him the right to request reasonable accommodation of his religious practices. Finally, although apparently not required to do so by any regulation, appellant’s commander generously allowed appellant to deploy with his unit in a non-combatant role....

As the Supreme Court has stated, “to accomplish its mission the military must

foster instinctive obedience, unity, commitment, and esprit de corps.” ... “The inescapable demands of military discipline and obedience to orders cannot be taught on battlefields; the habit of immediate compliance with military procedures and orders must be virtually reflex with no time for debate or reflection.”

Sounds quite right to me. I should also add that the Supreme Court held in Gillete v. U.S. (1971) that people weren't entitled to a religious exemption from the duty to serve in the military, beyond what was provided by the limited conscientious objector exception (which applies only to those who object to all military service, rather than to those who refuse to fight in what they see as "unjust" wars). Gillette was decided during the era when the Court viewed the Free Exercise Clause as providing a presumptive right to religious exemptions; the Court later reversed that position, but the Religious Freedom Restoration Act basically reinstated the Gillette-era religious exemption doctrine as to the federal government, so Gillette would still be good precedent as to RFRA cases (though for some reason the Army Court of Criminal Appeals didn't cite it).

Why Normative Markets?

In my last post, I described and gave a general argument for normative prediction markets. If a prediction market forecasts an evaluation by someone to be selected randomly from a body of very educated people (somewhat analogous to the federal judiciary, though perhaps selected in a way that makes it more representative), it will be an informed forecast of an informed decision, and the uncertainty about who the eventual decision maker will be provides for a kind of virtual representativeness.

Now, I'll describe several advantages of normative markets that follow:

(1) More consistent, predictable decision making. The virtual representativeness reduces the danger of idiosyncratic decision making. Of course, there will be some decisions that fall close to the line, but we avoid some situations where it's clear that 2/3 of decision makers would make one decision, but it happens to be someone in the 1/3 of decision makers who gets the final call.

If we can have more consistent, predictable decision making, we also may see a general shift from legal rules to standards. A powerful argument for rules over standards is that only rules can produce consistent and predictable decision making. With normative markets deciding whether legal provisions are followed, standards become relatively more attractive.

(2) More principled decisions. Suppose there is some higher order principle X that the group has precommitted to in advance. Now, we have to make a decision about whether something that the group has decided to do, Y, would be consistent with that high-level principle.

With conventional decision making, the decision maker may well sacrifice X for Y. X may be more important to a decision maker than Y, but a disingenuous argument that Y is consistent with X makes it only slightly less likely that X will be followed in the future. Those who have read Mistretta v. United States should understand what I am talking about.

This is less likely with normative markets, because the evaluation of whether Y is consistent with X will not actually affect whether the group can do Y. That decision has already been made. So, a precommitment to using normative markets can help improve the chance that the group will follow through on its substantive precommitments.

(3) More insulated decisions. It should be harder for a special interest group to influence decision making with normative markets. (Assume for the sake of argument that special interests make decision making worse rather than better.) The judiciary is relatively immune from special interests, and so too could be the pool of ex post evaluators.

A special interest group could try to affect the pool of ex post evaluators, but with many evaluators, each making only a small number of randomly selected decisions on a large number of potential topics, this won't be easy. Moreover, bribing the ex post evaluator would not be enough; the special interest group would have to commit credibly to bribing the evaluator, because the actual ex post decision would not matter.

(4) More scalable decisions. We can easily change the probability that a case is submitted to an ex post evaluator. More decisions would require more subsidies, but we don't have to hire and select more decision makers. Market participation should grow in proportion to subsidies.

Consider, for example, immigration review. From one perspective, this might seem to be one of the worst contexts for prediction markets, because they seem impersonal. But our current system of immigration may be inhumane and capricious. Normative markets could at least eliminate backlogs, in addition to providing more consistent decision making.

Nineteenth-century prediction markets:

Those who are interested in Mike Abramowicz's prediction markets posts may also be interested in this new NBER working paper I just saw on SSRN:

Historians have long wondered whether the Southern Confederacy had a realistic chance at winning the American Civil War. We provide some quantitative evidence on this question by introducing a new methodology for estimating the probability of winning a civil war or revolution based on decisions in financial markets. Using a unique dataset of Confederate gold bonds in Amsterdam, we apply this methodology to estimate the probability of a Southern victory from the summer of 1863 until the end of the war.

Our results suggest that European investors gave the Confederacy approximately a 42 percent chance of victory prior to the battle of Gettysburg/Vicksburg. News of the severity of the two rebel defeats led to a sell-off in Confederate bonds. By the end of 1863, the probability of a Southern victory fell to about 15 percent. Confederate victory prospects generally decreased for the remainder of the war.

The analysis also suggests that McClellan's possible election as U.S. President on a peace party platform as well as Confederate military victories in 1864 did little to reverse the market's assessment that the South would probably lose the Civil War.

This paper is also available directly on the NBER site, though I'm not sure whether the general public has free access to it.

Assessing the Economic Impact of Banning Economic Development Takings:

The Institute for Justice (the libertarian public interest law firm that represented the property owners in Kelo v. City of New London) has an interesting study assessing the economic impact of post-Kelo reform laws that ban Kelo-style economic development takings.

Contrary to the "doomsday" predictions of planners and local government officials who claimed that eliminating economic development takings would drastically stifle development, the study finds that states with strong post-Kelo reform laws have not suffered any reduction in growth and development relative to preexisting trends or in comparison with states that passed ineffective reforms or none at all.

I tend to agree with the study's conclusion that takings for economic development aren't actually necessary to increase employment or promote local economic growth. For reasons I outlined in this article, economic development takings are likely to do more harm than good for local economies.

At the same time, I think that the IJ study is not yet a definitive assessment of the economic impact of post-Kelo reform laws. All but one of the laws considered in the study have been in force for less than two and one half years (Utah, which enacted its reform law a few months before Kelo came down on June 23, 2005, is the exception). It is probably too early to fully assess their longterm impact. In addition, while the study controls for preexisting economic trends, it doesn't take account of intervening events other than post-Kelo reform laws that might affect economic development in different regions of the country.

The IJ study is a compelling refutation of the more extreme doom and gloom predictions of Kelo defenders. In my view, time will show that banning economic development takings is a boon for local economies, not a detriment. A few state Supreme Courts, such as Washington's (1959) and Kentucky's (1979), banned economic development takings under state constitutions many years before Kelo; there is no evidence that their actions undermined their states' economies in any way. Development economists have long argued that protecting property rights is a good way to promote growth. If landowners' rights are protected, they are more likely to invest in their properties and establish enterprises that stimulate local economies.

However, it will probably take several years for us to accumulate more definitive data on the impact of post-Kelo reform laws. In the meantime, the IJ study, combined with other available evidence, has shifted the burden of proof to those who argue that economic development takings are an essential tool for promoting local economic growth. It is up to them to show that forcibly displacing homeowners and businesses for the benefit of other private interests really is a good way to promote economic growth.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST WATCH: As longtime VC readers know, I have done considerable pro bono work for IJ, including writing several amicus briefs on their behalf.

Normative Prediction Markets:

Suppose that you are a member of a large group that has a large number of decisions to make. It might seem that you have two basic choices.

First, allow everyone to vote on every decision. This approach produces high representativeness (at least if everyone votes), but the votes will be based on little information. Second, allow a subset of the group to make each decision. This approach reduces representativeness, but allows for more informed decision makers.

Democratic institutions combine these two basic approaches in elaborate ways to overcome the trade-off between unrepresentative and uninformed decision making. All enfranchised citizens select a few citizens to serve as legislators, for example, and legislators divide into committees. For different types of decisions, we accept different trade-offs. Three-judge panels are unrepresentative but informed, so in theory we allow them to resolve legal questions but not to change national policy.

None of these solutions is perfect, and we face the usual perils of republican decision making: ignorant voters, special interests, legislative inertia, activist judges, and executive policies highly sensitive to the quadrennial preferences of a small number of voters in places like Florida and Ohio. But we may well structure voting regimes reasonably efficiently given the fundamental trade-off.

There is, however, a way of overcoming this basic trade-off using prediction markets rather than votes. We can commit to selecting someone at random from our group, or from a subset of it, to say what the decision should be. We will require this person to listen to detailed arguments and to produce a detailed explanation. But this will not be our decision. Instead, our decision will be based on the forecast generated by a “normative prediction market” predicting what this person will conclude is best.

Moreover, we don’t even need to have someone conduct this evaluation for every decision. We can use a pseudo-random number generator to pick only, say, one-tenth of the decisions for ex post evaluation. Before we make the random selection, we run a conditional normative market, where the condition is that the decision is selected for ex post evaluation. But every time, it is the market’s prediction that we will use as the decision.

A summary of the steps: (1) Subsidized conditional market predicts decision. (2) This prediction determines the group’s actual decision. (3) Random number from 0 to 1 is drawn; if it’s greater than 0.10, all money from market is returned. (4) Person is picked at random from group, and must eventually announce what he or she would have decided. (5) This evaluation is used to determine payouts in the conditional market.

This is a radically new way of making decisions, and I emphasize in the book that there are strong reasons not to transform radically our democratic institutions. I use dramatic examples (e.g., prediction market legislatures, trial by market) to illustrate the approach colorfully, but I don’t believe we should rewrite the Constitution. Normative markets could serve as useful inputs into more traditional decision making (change step 2 above to “This prediction provides a recommended decision.”), or be used in private settings.

All I want to show here is that this approach, which could also be used in private settings, helps overcome the trade-off between unrepresentative and uninformed decision making.

If the prediction market is sufficiently subsidized, then the prediction can be highly informed. Since we only have a few decisions that need ex post evaluation, and only one decision maker per decision, we can demand a lot of the ex post decision maker, who will then become informed too. Picking a random citizen might not be the best strategy, since an informed dolt is still a dolt, so we might have the ex post evaluator randomly drawn from a body akin to a judiciary (experts selected by indirectly elected representatives).

Meanwhile, the system provides a virtual representativeness. Traders don’t know who the actual ex post decision maker would be, so they will average the anticipated decisions of a broad ideological range of potential decision makers. We may be able to increase representativeness still further by delaying decisions a decade or so, so it won’t matter if we happen to have an unbalanced set of ex post decision makers at any one time.

Critically, it doesn’t matter if the actual ex post decision maker makes a foolish or unrepresentative decision. What matters is the average expected decision, because it is only the prediction of the ex post evaluation that determines policy.

Of course, my claims here depend on my earlier claims that prediction markets will be sufficiently accurate and deliberative.

Federalist Society Panel on Executive Power:

The Federalist Society has posted a video of the January 3 faculty conference panel on executive power, featuring Harvey Mansfield, John McGinnis, Neomi Rao, and our own Ilya Somin. (Sandy Levinson was also scheduled to be on the panel; to everyone's disappointment, he did not make it.) Although Ilya and I have stark disagreements about the proper role of the courts, we're mostly on the same page here. If hearing from only one VC blogger isn't enough for you, check out the Q&A. I ask the first question at the 34-minute mark; co-blogger David Bernstein asks the second question at the 39-minute mark; and fellow co-blogger Randy Barnett asks a question at the 60-minute mark.

Supreme Court Stays Eleventh Circuit Execution:

Lyle Denniston has the background here, and the stay order here. The obvious question is, does this tell us anything about what the Court might be doing with Baze v. Rees? I think the answer is "no." There are a bunch of reasons for this, but the biggest is a practical one: Even if the Court is likely to rule for Kentucky in the Baze case, denying the application for a stay in this case would leave the lower courts hopelessly confused as to whether executions will be allowed (and in what circumstances) before Baze is handed down. The whole point of taking Baze was to end lower court confusion and settle this issue clearly. So no matter how the initial conference vote went in the case, the sensible course is to stay all executions while the case is still pending.

Thursday, January 31, 2008

A Working Definition of Terrorism.

My colleague at the University of Utah College of Law, Amos Guiora, has just posted this very interesting paper on the appropriate definition of "terrorism." Here's the main point:

"The recommended definition captures the core elements of terrorism in clear and concise language. In reviewing scholarship and terrorists' writings, the overwhelming impression is that causing harm (physical or psychological) to the innocent civilian population is the central characteristic of terrorist action. The available literature articulates that harming civilians is the most effective manner from the terrorist mindset to effectuate their goals."

Guiora goes on to argue that, without a clear definition of terrorism, we won't take appropriate countermeasures. In particular, we need to understand that terrorism intends to disrupt daily life, and that effective counterterrorism measures will have to be based on that fact.

John McCain and the Judiciary:

Much controversy has centered recently around John McCain's possible judicial nominees should he become president. In my view, a President McCain would face a difficult tradeoff between the goal of appointing conservative jurists and the goal of saving the McCain-Feingold law from invalidation by the Court.

John McCain may well be sincere in claiming that he wants to appoint conservative justices. However, he is undoubtedly even more sincere in his support of the McCain-Feingold campaign finance law, his proudest achievement as a legislator. The narrow conservative majority on the Supreme Court is not fond of McCain-Feingold and has already significantly narrowed its scope in the Wisconsin Right to Life case. The five conservatives most likely believe that McCain-Feingold is unconstitutional; that applies also to swing voter Anthony Kennedy, who voted to strike down most of McCain-Feingold in McConnell v. FEC, the 2003 decision that narrowly upheld the law by a 5-4 margin (here is Kennedy's strong dissent in that case).

If he wants to have any chance at all of saving McCain-Feingold, a President McCain will have to appoint justices committed to upholding it. As a practical matter, however, there are few if any conservative jurists who are both 1) qualified to sit on the Court, and 2) likely to vote McCain's way on campaign finance issues; I can't think of even one offhand. Almost any well-known jurist likely to vote the conservative way on federalism, property rights, abortion, and other major constitutional issues is also likely to be just as committed to striking down McCain-Feingold as the conservatives currently on the Court. Thus, McCain will be strongly tempted to appointmoderate to liberal justices or a "stealth" candidate like Justice Souter with no clear judicial philosophy. The stealth approach failed for George W. Bush when the Harriet Miers nomination blew up in his face. However, McCain might do better with it, since he would be facing a Democratic-controlled Senate rather than a Republican one.

I honestly don't know whether McCain - should he be elected - would put his desire to uphold McCain-Feingold above his campaign promises to appoint conservative justices. However, the possibility that he might appoint an analogue to Justice Souter or Harriet Miers in order to save McCain-Feingold is a very real one. This concern is only slightly assuaged by recent endorsements of McCain by conservative legal luminaries such as Ted Olson and Miguel Estrada. Perhaps they know something about McCain's plans that I don't. However, it will take a lot more evidence to convince me that McCain is genuinely willing to set his commitment to McCain-Feingold aside in making Supreme Court appointments.

Supreme Court appointments are not the only issue in the presidential election and probably not the most important. However, conservatives and libertarians who care about legal issues should be aware of the possibility that a President McCain might end up appointing justices likely to vote against their positions on most major constitutional issues before the Court. The above is not an endorsement of Mitt Romney, who has his own shortcomings. Nor is it a comprehensive rejection of McCain, whose positions on some issues I very much agree with. It does, however, flag an important concern about McCain's potential judicial appointments.

James Risen Subpoenaed:

The New York Times reports on an interesting development in the investigation of leaks concerning classified counter-terrorism programs.

A federal grand jury has issued a subpoena to a reporter of The New York Times, apparently to try to force him to reveal his confidential sources for a 2006 book on the Central Intelligence Agency, one of the reporter’s lawyers said Thursday. . . .

Mr. Risen’s lawyer, David N. Kelley, who was the United States attorney in Manhattan early in the Bush administration, said in an interview that the subpoena sought the source of information for a specific chapter of the book “State of War.”

The chapter asserted that the C.I.A. had unsuccessfully tried, beginning in the Clinton administration, to infiltrate Iran’s nuclear program. None of the material in that chapter appeared in The New York Times. . . .

Mr. Risen, who is based in Washington and specializes in intelligence issues, is the latest of several reporters to face subpoenas in leak investigations overseen by the Justice Department. . . .

Ms. Mathis would not say why the material about the C.I.A. program involving Iran appeared in Mr. Risen’s book but not in pages of The Times. “We don’t discuss matters not published in The Times,” she said.

The Justice Department would not comment on the work of the grand jury that issued the subpoena to Mr. Risen. “The department does not comment on pending investigations,” said Peter Carr, a spokesman.

Crime Victims' Right to Object to a Plea Agreement:

I'm working on an interesting pro bono case involving the crime victims' right to object to a plea agreement in federal court under the Crime Victims Rights Act. It arises out the Texas City Refinery explosion in March 2005, which left 15 dead, hundreds injured, and untold property damage.

Recently the responsible corporation -- BP Products North America -- agreed to pled guilty to a criminal violation of the Clean Air Act. But the plea agreement is a "binding" plea agreement -- that is, the judge would have no discretion in sentencing. The plea agreement obligates BP Products North America to pay a $50 million fine and do essentially nothing more to ensure plant safety than abide by previous agreements with federal and state regulators.

Along with other pro bono lawyers in Texas, I represent some of the victims of the explosion. They would like the judge to reject the plea and send the parties back to the drawing board to negotiate more safety measures and a more appropriate -- and tougher -- penalty.

Today the other lawyers and I filed pleadings in the federal district court in Texas. Our pleadings argue the court should reject the plea because the proposed plea blocks the court from appointing its own independent safety monitor to supervise BP Products' environmental compliance. The pleadings also argue that since the statutory maximum fine in this case (based on the gain to the company or loss to the victims) is more than $2 billion, a substantially larger fine is appropriate.

The larger issue here is what role the fedeal courts will give crime victims in these kidns of issues. Under the new Crime Victims Rights Act, crime victims have the right to "heard" on any proposed plea. On Monday, I will be in Houston helping victims exercise that right.

Miguel Estrada Supports John McCain, Too:

Again from Jennifer Rubin (Commentary): "Conservative lawyer, former Assistant to the Solicitor General and filibustered federal appellate court nominee Miguel Estrada says 'McCain' as well." For those who don't know, Miguel is both brilliant and solidly conservative. Related Posts (on one page): - Miguel Estrada Supports John McCain, Too:

- Ted Olson Endorses John McCain:

Symposium at Catholic University (in D.C.) on Justice O'Connor's Jurisprudence Related to Race and Education:

Looks like a very interesting program, and a quick glance suggests it's a pretty balanced lineup. It will be happening on Friday, February 22.

Responding to Shellenberger & Nordhaus on Climate:

On Monday, Michael Shellenberger and Ted Nordhaus, authors of Break Through: From the Death of Environmentalism to the Politics of Possibility, challenged conservatives on global warming in an essay on TNR Online. While some conservatives (including yours truly) have acknowledged the threat of climate change, Shellenberger and Nordhaus wrote, few (if any) had followed through with tangible proposals for meaningful action.

Newt Gingrich and Terry Maple, authors of the conservative environmental manifesto, A Contract with the Earth, responded on Tuesday, arguing for a market-based approach of sorts, based on "bold government incentives," to the threat of climate change. Shellenberger and Nordhaus were not convinced by the Gingrich-Maple argument, and suggested Gingrich and Maple are trying to address climate change "on the cheap," and that won't do.

I contributed to the exchange today, suggesting that Nordhaus and Shellenberger are too wedded to centralized, top-down strategies. even though Shellenberger and Nordhaus recognize the difference between a politics of limits and one of possibility, they do not seem to comprehend the problems common to all centralized, top-down policy initiatives--regulatory and subsidy-driven alike. In their book and essays, Shellenberger and Nordhaus correctly observe that regulatory approaches to climate change are "economically insufficient to accelerate the transition to clean energy." Yet the "investment-centered" approach they prefer still suffers from substantial limits, not least their preference for a centrally directed system of subsidies. Rather than grapple with the limits of top-down direction of investment and economic activity, they present a false dichotomy between laissez faire absolutism and government direction of investments. . . .

There is certainly a need for conservatives and others to "back up words with action," but not just any action will do. We need innovation-spurring, forward-looking environmental policies, not a repackaging of the centralized mandates and economic controls that have dominated environmental policy for the past three decades. Shellenberger and Nordhaus have helped to initiate this dialogue, but their policy recommendations should not be the last word. The essay fleshes out some of what I have in mind in greater detail.

My prior posts on Nordhaus and Shellenberger, and their provocative book, are here and here. Meanwhile, while we're on the subject of conservatives and climate change, David Roberts rounds up the latest comments from the GOP presidential candidates on global warming policy.

Ted Olson Endorses John McCain:

From Jennifer Rubin at Commentary: "Ted Olson, fomer U.S. Solicitor General and conservative legal icon, has just informed me that he is endorsing John McCain."

Novak on McCain & Judicial Nominations:

Today's Robert Novak column supports John Fund's claim that Sen. McCain has made comments suggesting he would be unlikely to nominate someone like Samuel Alito to the Supreme Court. Specifically, Novak reports the following:

Fund wrote that McCain "has told conservatives he would be happy to appoint the likes of Chief Justice Roberts to the Supreme Court. But he indicated he might draw the line on a Samuel Alito because 'he wore his conservatism on his sleeve.' " In a conference call with bloggers that day, McCain said, "I don't recall a conversation where I would have said that." He was "astonished" by the Alito quote, he said, and he repeatedly says at town meetings, "We're going to have justices like Roberts and Alito."

I found what McCain could not remember: a private, informal chat with conservative Republican lawyers shortly after he announced his candidacy in April 2007. I talked to two lawyers who were present whom I have known for years and who have never misled me. One is neutral in the presidential race, and the other recently endorsed Mitt Romney. Both said they were not Fund's source, and neither knew I was talking to the other. They gave me nearly identical accounts, as follows:

"Wouldn't it be great if you get a chance to name somebody like Roberts and Alito?" one lawyer commented. McCain replied, "Well, certainly Roberts." Jaws were described as dropping. My sources cannot remember exactly what McCain said next, but their recollection is that he described Alito as too conservative.

Predicting Decisions and Their Effects:

So far, my posts have implicitly assumed independence between forecasts and decisions. Now, let’s consider some ways in which we might structure prediction markets to forecast the decisions themselves and their consequences, so that the forecasts might influence the decisions.

(1) Markets predicting decisions. A market that predicts a decision might end up affecting the decision. Suppose that Eugene is elected dictator, but because of his blogging responsibilities, His Tremendousness must make many decisions. So, he establishes prediction markets forecasting what decisions he will make.

Now, Eugene is presented with a decision to make, and he quickly analyzes the problem and leans toward Decision A. But then he checks the market and sees that it forecasts that he will make Decision B. He wonders, why is that? He looks more carefully and realizes that he has missed some aspects of the problem.

Some of the dynamics of the deliberative market are present here. A trader predicting a decision can profit by developing arguments that will persuade the decision maker. For example, the trader can write an argument for Decision A and bet on Decision A just before releasing the argument. Eugene might thus create a market predicting his decisions as a way of generating research and arguments relevant to those decisions.

(2) Conditional markets. A conditional market predicts some variable contingent on a condition. A simple way to run such a market is to stipulate that all money spent on the prediction market will be refunded if the condition does not occur. For example, one market could predict a corporation’s stock price if a corporation decides to build a factory, and a separate market could predict the stock price if it doesn’t build the factory. The corporation can compare the forecasts to assess the market’s perception of the effect of building the factory on stock price.

These are a useful tool, but there are important caveats. First, small deviations between two markets can’t be taken too seriously. If Market A predicts a stock price of $30.00 and Market B predicts a stock price of $30.01, the difference could just be noise. Relatedly, if the condition will have little effect on the stock price, even subsidized prediction markets will give people little incentive to study the effect of the condition. Instead, the subsidy will just give general incentives to study all factors that might affect future stock price.

Second, traders will recognize that information unknown to them may affect the decision. For example, last May, Hillary Clinton’s chance of winning the Presidency conditional on being nominated was estimated based on prediction markets at over 70%. That could indicate that Clinton was a strong candidate. It also could mean that the Democrats would stick with a weak candidate like Clinton only if other factors, like the economy, were pointing so strongly in the Democrats’ direction that Democratic primary voters did not care about electability.

In our next installment, I’ll show that “normative markets” combine the two market approaches considered above.

If I Were a Senator or Governor Who's Also a Presidential Candidate,

I'd file an amicus brief in the Supreme Court's Second Amendment case supporting the individual right to bear arms (but with room for an unspecified range of "reasonable restrictions"). I'd then tout my position, and question the views of those of my rivals who didn't file such a brief.

Not that I'd expect the brief to matter much to the Court -- but I'd think it would be pretty good for my campaign, certainly if I'm a Republican but maybe even if I'm a Democrat who wants to appeal to the many pro-gun-rights Democrats and independents. Or am I mistaken?

Why Check With People Before Responding to Their Off-Hand Remarks?

Earlier this morning, I wrote:

It's true that blog posts are often less thought-through than articles or op-eds.... It therefore makes sense to check with the author before citing the post, in case the author wants to elaborate on it, or even recant it in some measure -- it's not necessary, but it can be helpful.

Tim Sandefur responded:

I must say I really disagree with the "check with the author" thing. Why? I never check with the author of a law review article or a book when I cite them. I can see that in some cases it might be helpful if you think the author could expand on some point, but that would probably be best done in a new post by that blogger.

When I cite a blog it is very often because I am citing someone whose views are contrary to mine, and if there were any point of etiquette that counsels me to ask permission or anything, that person would then refuse (or alter the blog post) and deprive me of a helpful reference. The fact that people can retroactively alter their blog posts makes it especially likely that a person who made a comment that later proves embarrassing will then try to weasel out of it when he's called on it in the form of a law review citation.

In my view, there's no more reason to request permission before citing in a law review than there is to request permission before linking to it from my own blog and criticizing it. If the person then chooses to alter the blog post or elaborate or whatever, that's fine, but why should I give him a chance to cover up his tracks before I criticize him?

Now, obviously blogs are, as you say, off-the-cuff, and they should be cited with that in mind (and if cited, should be read with that in mind). And you do say that there's no "rule" here, but I still don't think there's any reason to set out some guideline of etiquette that counsels any obligation on the part of a reader or writer to ask permission before citing a blog post. And I think there is an obvious downside in a bloggers' ability to go back and change his statements.

Here's my thinking: None of this is a matter of needing "permission" -- but it is a matter of making sure that debates are based on real disagreements, and not on misunderstandings, silly mistakes, or qualifiers that are omitted in the course of a casual conversation.

Say you say in a quick blog post, "Content-based speech restrictions are unconstitutional," and I have a paragraph in your article saying, "Some scholars argue that content-based speech restrictions are unconstitutional, but they're wrong -- after all, libel law, obscenity law, and many other constitutionally permissible laws are content-based." But you didn't really mean to argue that content-based speech restrictions are unconstitutional; you just omitted a "generally," or some other qualifier. What's the point of the back and forth? How does it help the reader, or the state of professional knowledge?

Or say you accidentally omit a "not" or an "un-," or make a similar typing error (not uncommon in quickly written prose). And say you don't notice this and your readers don't tell you (maybe you don't have a lot of readers who help you by sending corrections, or maybe they just weren't paying attention to this post). I then write "X says that content-based speech restrictions are constitutional, which shows what a minimalist he is when it comes to free speech" -- but it turns out I'm arguing not with your sincere beliefs or your edited prose, but with your slip of the finger. What's the point?

Nor is there much reason to worry, I think, about the person "covering his tracks" by modifying the post. If the original post is somehow especially telling, you can always cite the original (just save a copy of the original version, and note in your footnote that you're citing to the original version and not the updated one). Thus, for instance, if you think the original post really reflects the speaker's true views, and the revision is an attempt to disingenuously hide the beliefs that slipped out in a rare moment of candor, go ahead and cite to the original.

But if the person e-mails back sincerely saying, "Thanks -- I misspoke, and I've corrected the post to more accurately reflect my views [or the state of the law]," then what have you lost? At most the opportunity to engage in a debate with a view that might not actually be held by anyone, or to represent the post as your target's true views when it's actually just an error. Pat yourself on the back for being nice, and, more importantly, for sparing your readers a pointless debate against a view that even your target doesn't actually hold.

Now some of this is specific to law review articles that cite blog posts. If you're citing an article, you can be more confident that the author really means what he says there, because the author has likely reread the article several times, and confirmed that he didn't just misspeak. If you're writing a blog post that cites another blog post, you might not want the delay that often accompanies such queries. But if you're writing a law review article, you have the time to check things, and good reason to avoid needless debates.

Community Morality and Zoning Restrictions on Adult Businesses and Military Recruiting Stations:

In addition to the measures against military recruiters described in Eugene's recent posts, Berkeley is also considering enacting a zoning ordinance to restrict their location in much the same way as other cities use zoning to restrict or ban businesses selling pornography: