|

Saturday, July 7, 2007

Boycotting the British UCU Boycott of Israel:

This morning I received the following note from Professor Steve Lubet of Northwestern University Law School that I thought would be of interest to VC readers.

Dear Colleagues:

As you probably know, the British University and College Union recently passed a resolution advancing a boycott of Israeli scholars and academic institutions. Whatever your political views on the Middle East, I trust you will agree that such a boycott is antithetical to academic principles. It shuts off dialogue, when one of the key purposes of universities is to promote dialogue and thereby the pursuit of truth. It ignores existing projects where Israeli and Palestinian academics cooperate. It requires academics to hew to one ideological line. And it constitutes discrimination on the basis of nationality. Many leading international scholars — including Palestinians — have issued statements in opposition to a boycott, recognizing that it violates essential academic values. In the words of Lee Bollinger, President of Columbia University, "In seeking to quarantine Israeli universities and scholars this vote threatens every university committed to fostering scholarly and cultural exchanges that lead to enlightenment, empathy, and a much-needed international marketplace of ideas."

If you agree that the UCU boycott resolution is wrong, you may show your opposition by signing the petition circulated by Scholars for Peace in the Middle East (SPME). It has already been signed by numerous Nobel Laureates and university presidents.

The text of the SPME petition is as follows:

We are academics, scholars, researchers and professionals of differing religious and political perspectives. We all agree that singling out Israelis for an academic boycott is wrong. To show our solidarity with our Israeli academics in this matter, we, the undersigned, hereby declare ourselves to be Israeli academics for purposes of any academic boycott. We will regard ourselves as Israeli academics and decline to participate in any activity from which Israeli academics are excluded.

To sign the statement, go here. A list of signatories is available here. Note that one need not support Israeli policies, or even the positions of SPME, to support this statement. Academic boycotts of this sort are, quite simply, contrary to the ideals of open intellectual discourse.

Glendon and Kmiec on OT2006:

Mary Ann Glendon and Douglas Kmeic offer this Legal Times commentary on the Supreme Court's OT2006 and the roles of Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito.

Despite some ideological carping from those who lost cases that depended upon the extension of past decisions, Roberts and Alito have also shown themselves to be strongly respectful of precedent. Advocates this term urged overturning previous abortion decisions, a Warren Court ruling allowing taxpayers to sue in religion cases, and campaign spending limits. The new justices left those precedents in place, often resisting both their unwarranted extension to new facts and the urging of Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas to overrule them.

This cannot fairly be dubbed faux deference. Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District (1969) still meaningfully invites robust discussion of political and social views in school, as Alito and Kennedy strongly reaffirmed in Morse v. Frederick, even though Tinker did not protect advocacy of illegal drug use. Likewise, the allowance in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) for race as one factor in pursuit of higher-education diversity was reaffirmed, notwithstanding the Court’s rebuff of outright racial balancing.

"Those Who Cure You Will Kill You":

It is quite disturbing that those involved in plotting the foiled terror plots in Britain were trained in medicine. Unfortunately, such perversions of medical obligations are nothing new. As my former colleague Amos Guiora recounts, the leadership of Hamas included a doctor who justified his support of terrorism by suggesting there were two of him -- one who cured and one who killed.

Biotech Can Boost Milk Production:

Milk prices are up, and may well go higher. What can be done about it? Dr. Henry Miller, a former FDA official now with the Hoover Institution, has an idea: One way to ease the shortage and lower the prices is to take greater advantage of a proven 13-year-old biological technology that stimulates milk production in dairy cows — a protein called recombinant bovine somatotropin (rBST), or bovine growth hormone. The protein, produced naturally by a cow’s pituitary, is one of the substances that control its milk production. It can be made in large quantities with gene-splicing (recombinant DNA) techniques. The gene-spliced and natural versions are identical.

Bad-faith efforts by biotechnology opponents to portray rBST as untested or harmful, and to discourage its use, keep society from taking full advantage of a safe and useful product. The opponents’ limited success is keeping the price of milk unnecessarily high.

When rBST is injected into cows, their digestive systems become more efficient at converting feed to milk. It induces the average cow, which produces about eight gallons of milk each day, to make nearly a gallon more. More feed, water, barn space and grazing land are devoted to milk production, rather than other aspects of bovine metabolism, so that you get seven cows’ worth of milk from six. Dr. Miller's op-ed prompted lots of responses, some of which are available here.

I find it interesting that opposition to rBST largely consists of what economist Bruce Yandle termed a "baptist and bootlegger" coalition. The "baptists" are ideological interests, such as anti-biotech activists and animal welfare groups. The "bootleggers" are small and boutique dairy farmers concerned that rBST can increase the competitive advantage of larger dairy producers. Such combinations of ideological and economic interests are common in environmental law, and can be quite influential.

Friday, July 6, 2007

No Fourth Amendment Protection in E-Mail Addresses, IP Addresses, Ninth Circuit Holds:

Commentators and Congress have long assumed that government surveillance of non-content "header" information like e-mail addresses and IP addresses, typically done by a service provider, do not violate a Fourth Amendment "reasonable expectation of privacy." Today the Ninth Circuit became the first court to hold this directly in United States v. Forrester. My major concern with this opinion is that, unless I'm missing something, the opinion does not actually say how the surveillance occurred. The Court states that the government used "a pen register analogue on [the defendant]’s computer" to collect the IP address, to/from e-mail addresses, and total volume transferred. But the reader is left guessing what that means. Consider two possibilities. The first possibility is that the government served the order on the ISP, and that the information was collected at the ISP. If so, the analogy to Smith v. Maryland is really clear, and the result in Forrester is clearly correct. The second possibility is that the Court meant what it said literally: the government installed a pen register analogue "on [the defendant's] computer," which seems to suggest some kind of surveillance device actually inside the person's machine. If that's right, I tend to think this is a different case. At that point the facts become a lot more like United States v. Karo, the locating device case, where the use of a surveillance device inside the home was held to be a search. So which one of these sets of facts occurred? We don't know, as best as I can tell, and without knowing I find it hard to tell if I agree with the decision. More broadly, it will be hard for other courts to know what to make of the precedent: Is the court saying that the government can remotely install a surveillance device on your personal machine so long as the information collected doesn't implicate a reasonable expectation of privacy? Or are they only saying that the provider can collect that information from inside the provider's network on the government's behalf? Maybe I'm just missing the part of the opinion that explains this? If so, please let me know in the comment thread. And thanks to Terry Edwards for the link. Related Posts (on one page): - Amended Opinion in Forrester:

- Can the FBI Install Spyware on Your Computer Without A Warrant?:

- No Fourth Amendment Protection in E-Mail Addresses, IP Addresses, Ninth Circuit Holds:

Why Isn't He Running for President?

I happened to catch on one of my local NPR stations this afternoon a talk that Colin Powell gave at the Aspen Institute a few days ago, focusing on the Iraq war. Maybe it's just me, but to my ears Powell is the only one out there who talks sense about the war — why it matters, what mistakes we've made, how to move forward from here, without unnecessary hand-wringing and finger-pointing. Plus, I don't think any of the candidates out there can come close to him when he talks about why the idea, and ideals, of America are important and even inspiring. I don't know about anyone else, but I'd vote for him in a NY minute, and I suspect there are lots and lots of folks out there who feel the same way.

Correction Regarding the Courthouse Russian Jesus Icon:

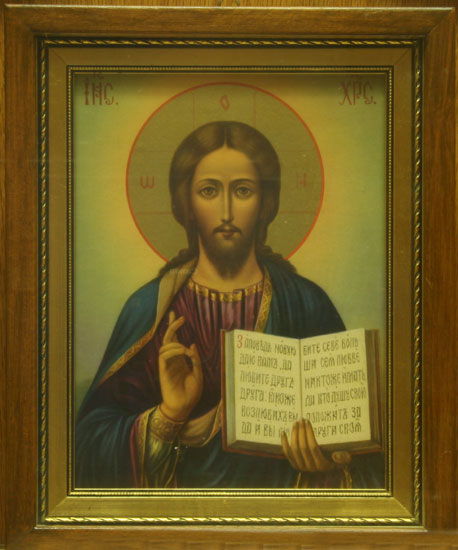

The blog post on which I relied for a copy of the icon appears to have been incorrect. The correct photo, according to AP and Yahoo! News Photos, is this:

I can't read the text, but this site, which discusses what appears to be this icon, independently of the Slidell controversy, reports that the text corresponds to John 7:24 ("Judge not according to the appearance, but judge with righteous judgement") and Matthew 7:2 ("For with what judgement you judge, you shall be judged"). This is indeed more courthouse-related text than what I understood the quote to be earlier. [UPDATE: The ACLU of Louisiana was kind enough to send me a more readable version, and Sasha, who knows how to read Old Church Slavonic -- which differs enough from standard, even pre-1918 standard, Cyrillic Russian that it requires special skill in reading -- was kind enough to transliterate it into Russian. With this, he and I can confirm that the text is a combination of John 7:24 and Matthew 7:2.]

Still, the bottom line seems to me to remain: To the extent the text matters, it's New Testament text; to the extent the text should be ignored, since the overwhelming majority of observers won't understand it, it's apparently a depiction of Jesus. In either case, it seems unconstitutional even under Justice Scalia's proposed test for a court to display the work in this context, as a standalone work in a court house with the caption "To know peace, obey these laws."

UPDATE: Thanks to commenter Paul Lukasiak for a pointer to the picture as it appears in context:

Related Posts (on one page): - ACLU of Louisiana:

- Correction Regarding the Courthouse Russian Jesus Icon:

Sixth Circuit Reverses Judge Taylor on NSA Surveillance Case:

Oops -- I see that my co-blogger Jonathan posted about this case while I was drafting my own analysis. Given that, I will "hide" my post below the fold.

The opinion of the Sixth Circuit is here, via Howard. The panel divided 2-1, with three separate opinions. Judge Batchelder and Judge Gibbons concluded that the plaintiffs lacked standing to sue because they had no evidence that they were actually subject to monitoring under the Terrorist Surveillance Program. As I understand it, the plaintiffs in the case had argued that they thought they might be covered by the TSP, but had no particular reason (other than the apparent existence of the program) to think they in fact had been or were to be monitored. Their claimed injury-in-fact was that they were holding back on sending international communications out of fear that they were being monitored. The main question in the case was whether this claim was sufficient to establish standing to challenge the legality of the TSP program. Judge Batchelder's opinion goes through the complaint claim-by-claim, explaining her reasons why the plaintiffs either lacked standing for each claim in light of this alleged injury or why the plaintiffs lost on the merits (or both). I am no expert in standing doctrine, but based on my quick read I tend to think this was the right approach and that the result seems correct. Judge Gibbons' opinion argues the standing issue more broadly, reaching the same result as Judge Batchelder. Judge Gilman dissented, arguing that the attorney-plaintiffs had alleged sufficient harm to have standing. Judge Gilman then reaches the merits of the case, concluding that "the Bush Administration's so-called 'Terrorist Surveillance Program'" violates FISA and rejecting the "inherent authority" claim. (Oh, and in case you're wondering at home, yes, the four opinions issued in this case do neatly match a political narrative. Judges Batchelder and Gibbons were appointed by Republicans, Bush Sr. and Bush Jr, respectively; Judges Gilman and Taylor were appointed by Democrats, Clinton and Carter.)

Plaintiffs Lack Standing to Challenge NSA Surveillance:

Today the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit held that none of the plaintiffs in American Civil Liberties Union v. National Security Agency have standing to challenge the program and dismissed the case. Judge Batchelder wrote the opinion for the court. Judge Gibbons delivered a separate concurring opinion, and Judge Gilman dissented. I can virtually guarantee that this is not the last we have heard of this case.

UPDATE: From Judge Batchelder's opinion for the court: in crafting their declaratory judgment action, the plaintiffs have attempted (unsuccessfully) to navigate the obstacles to stating a justiciable claim. By refraining from communications (i.e., the potentially harmful conduct), the plaintiffs have negated any possibility that the NSA will ever actually intercept their communications and thereby avoided the anticipated harm — this is typical of declaratory judgment and perfectly permissible. But, by proposing only injuries that result from this refusal to engage in communications (e.g., the inability to conduct their professions without added burden and expense), they attempt to supplant an insufficient, speculative injury with an injury that appears sufficiently imminent and concrete, but is only incidental to the alleged wrong (i.e., the NSA’s conduct) — this is atypical and, as will be discussed, impermissible.

Therefore, the injury that would support a declaratory judgment action (i.e., the anticipated interception of communications resulting in harm to the contacts) is too speculative, and the injury that is imminent and concrete (i.e., the burden on professional performance) does not support a declaratory judgment action. From Judge Gibbons concurring opinion: The disposition of all of the plaintiffs’ claims depends upon the single fact that the plaintiffs have failed to provide evidence that they are personally subject to the TSP. Without this evidence, on a motion for summary judgment, the plaintiffs cannot establish standing for any of their claims, constitutional or statutory. For this reason, I do not reach the myriad other standing and merits issues, the complexity of which is ably demonstrated by Judge Batchelder’s and Judge Gilman’s very thoughtful opinions, and I therefore concur in the judgment only. And from Judge Gilman's dissent: My colleagues conclude that the plaintiffs have not established standing to bring their challenge to the Bush Administration’s so-called Terrorist Surveillance Program (TSP). A fundamental disagreement exists between the two of them and myself on what is required to show standing and whether any of the plaintiffs have met that requirement. Because of that disagreement, I respectfully dissent. Moreover, I would affirm the judgment of the district court because I am persuaded that the TSP as originally implemented violated the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA). And: The closest question in this case, in my opinion, is whether the plaintiffs have the standing to sue. Once past that hurdle, however, the rest gets progressively easier. Mootness is not a problem because of the government’s position that it retains the right to opt out of the FISA regime whenever it chooses. Its AUMF and inherent-authority arguments are weak in light of existing precedent and the rules of statutory construction. Finally, when faced with the clear wording of FISA and Title III that these statutes provide the “exclusive means” for the government to engage in electronic surveillance within the United States for foreign intelligence purposes, the conclusion becomes inescapable that the TSP was unlawful. I would therefore affirm the judgment of the district court.

InAlienable Publicity Photo:

I thought those who read my live blogging (click link for all posts on one page) from the set of InAlienable last week might enjoy seeing these two publicity photos of the cast that I just received from photographer Michele K. Short. From left to right: Eric Avari, Richard Hatch, Courtney Peldon, Judy Levitt (Walter Koenig's wife), Walter Koenig, Marina Sirtis, and me (click on photos for larger image).

This picture is of just the "legal" characters:

Federalist Society Online Debate on the Al-Marri Decision:

The Federalist Society has posted an online debate about the Fourth Circuit's recent decision in Al-Marri v. Wright. The contributors were Richard Epstein, Andrew C. McCarthy, George Terwilliger, Erwin Chemerinsky, John Hutson, and myself. You can read the Justice Department's petition for rehearing in the Al-Marri case here.

Truth as a Defense in Defamation Cases:

A reader asked me whether true reputation-injuring statements are categorically immune from defamation liability. (Let's set aside for now invasion of privacy and other torts.) His state statute, he noticed, provided that such statements are protected only if they are said with "good motives" and for "justifiable ends."

Historically, many state statutes indeed so limited the truth defense. Today, I expect that such limitations would be unconstitutional: Defamation liability is said to be constitutional because "there is no constitutional value in false statements of fact," a rationale that doesn't apply to true statements. As to statements on "public issues," the Court has expressly rejected the good motives/justifiable ends limitation. But my sense is that such a limitation would be rejected as to private-concern statements, too; and I know of no modern cases that continue to apply the limitation.

Except, that is, for the remarkable case of Johnson v. Johnson, 654 A.2d 1212 (R.I. 1995). The facts:

On the evening of August 29, 1986, plaintiff entered Twin Oaks Restaurant in Cranston and proceeded to walk to the podium. While at the podium, plaintiff [ex-wife] saw defendant [her ex-husband] approach and ask her how her “[epithet] lawyer Fishbein” was. The defendant then drew nearer plaintiff who was standing with her then boyfriend-now husband Philip Caliri. At a distance of about four feet, in a loud voice, defendant screamed, “Phil, you are a * * * [epithet]. You could have prevented this case.” The defendant then pointed his finger in the face of plaintiff, while talking to Philip Caliri but screaming for all to hear, “You and that [obscenity] whore are costing me a lot of money.” ...

The ex-wife sued, claiming that the ex-husband slandered her by calling her a "whore," which in context appeared to mean someone who was unfaithful, not someone who was a prostitute. The court concluded the charges were true: "The findings of fact made by the trial justice are clear and unequivocal that the plaintiff fit the definition of the defamatory term applied to her." Yet the court went on to rule that, while "[i]n this case some spite and ill will might be understandable," "the trial justice was [not] clearly wrong when he confirmed the probable finding of the jury (although no special interrogatories had been submitted) that defendant acted out of spite and ill will."

Result: The compensatory damages award was upheld, on the theory that reputation-injuring but true statements on matters of private concern could still be actionable if said out of "malicious motives." The punitive damages award, however, was rejected, because in this case "defendant was the victim of a long course of reprehensible behavior committed against him by plaintiff."

I think this is an outlier case, which is inconsistent with the Court's false statement of fact jurisprudence, and which most American courts would not follow. Yet there it is, from the Rhode Island Supreme Court in 1995.

Thursday, July 5, 2007

Painting of Jesus in Louisiana Courthouse:

The New Orleans Times Picayune reports:

A portrait of Jesus Christ that hangs in the lobby of Slidell City Court violates the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, specifically a mandate calling for the separation of church and state, according to a federal lawsuit filed Tuesday by the Louisiana ACLU....

Vincent Booth, acting executive director and board president for the ACLU, said after filing the suit that he believes the portrait, along with lettering beneath that says, "To know peace, obey these laws," violates established U.S. Supreme Court law....

A local priest has identified the portrait as "Christ the Savior," a 16th Century Russian Orthodox icon. It depicts Jesus holding a book open to biblical passages, written in Russian, that deal with judgment. The ACLU says the book is the New Testament.

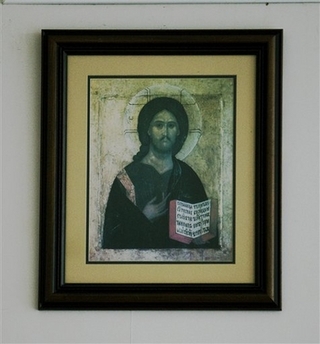

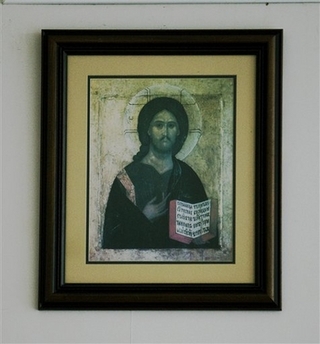

ERROR IN THE FOLLOWING TWO PARAGRAPHS AND THE PHOTO: The icon, according to this blog post, is this:

The reproduction is a little fuzzy, so I'm not positive about the entirety of the text; but at least the first two thirds are a Russian version of John 13:34, "A new commandment I give unto you, That ye love one another; as I have loved you, that ye also love one another." (For the modern Russian version, see here.) END ERROR.

CORRECTION: The blog post on which I relied for a copy of the icon appears to have been incorrect. The correct photo, according to AP and Yahoo! News Photos, is this:

I can't read the text, but this site, which discusses what appears to be this icon, independently of the Slidell controversy, reports that the text corresponds to John 7:24 ("Judge not according to the appearance, but judge with righteous judgement") and Matthew 7:2 ("For with what judgement you judge, you shall be judged"). This is indeed more courthouse-related text than what I understood the quote to be earlier. END CORRECTION.

My sense is that even under Justice Scalia's dissenting opinion (joined by Justice Thomas and Chief Justice Rehnquist) in one of the Ten Commandments cases, such an overt reference to Christianity and to a New Testament verse would be impermissible: Justice Scalia, after all, stressed that he viewed Ten Commandments displays as permissible because they are essentially endorsed by "such a broad and diverse range of the population — from Christians to Muslims — that they cannot be reasonably understood as a government endorsement of a particular religious viewpoint."

He also wrote that "The Establishment Clause would prohibit, for example, governmental endorsement of a particular version of the Decalogue as authoritative," and rejected Justice Stevens's argument that the Scalia approach would read the Establishment Clause as "protecting only the Christian religion or perhaps only Protestantism": "All of the actions of Washington and the First Congress upon which I have relied, virtually all Thanksgiving Proclamations throughout our history, and all the other examples of our Government's favoring religion that I have cited, have invoked God, but not Jesus Christ.

Perhaps Justice Scalia should have taken the broader view that the Establishment Clause allows all government endorsement of religion, or at least of Christianity generally; and it's possible that he took this view in the creche cases. But his Ten Commandments opinion takes a view that is more restrictive of government religious speech, and under this view it seems that the Slidell painting may not be displayed.

The Alliance Defense Fund, which has agreed to represent the court, responds:

"The First Amendment allows public officials, and not the ACLU, to decide what is appropriate for acknowledging our nation’s religious history and heritage. The painting clearly delivers an inclusive message of equal justice under the law," said ADF Senior Legal Counsel Mike Johnson. "It is mind-boggling that the ACLU would oppose such a widely cherished idea simply because it is offended by the image in the painting."

"The ideas expressed in this painting aren't specific to any one faith, and they certainly don’t establish a single state religion," Johnson explained. "The reason Americans enjoy equal justice is because we are all 'created equal, endowed by [our] Creator with certain unalienable rights.' This painting is a clear reflection of the ideas in the Declaration of Independence." ...

It's hard for me to see how such an ecumenical perspective can be read into a painting of Jesus holding a fragment from the New Testament (or, if the theory is that the text is irrelevant because next to no-one would understand it, we can just settle on this being a painting of Jesus with some undefined pronouncement), coupled with "To know peace, obey these laws," presumably referring to the laws expounded by Jesus.

Thanks to Frank Bell for pointers to the story and to the icon.

UPDATE: I should stress that this seems to be a standalone painting, and one that isn't just displayed as a work of art for art's sake — the "lettering beneath that says, 'To know peace, obey these laws'" suggests the court authorities are trying to send a normative message with the painting, not just to display a historically interesting or significant artifact.

The Supreme Court and the Libby Case -- A Dialogue:

Two lawyers, one very liberal and the other very conservative, meet over a beer to chat about recent legal stories in the news. . . .

Lib: I've been thinking a lot about the new Supreme Court. Those new Justices are totally political — they vote the conservative way every time. I'm just glad the more liberal justices kept opposing their efforts.

Con: Funny, I've been thinking about the Libby case. The case against Libby was totally political. I'm just glad President Bush undid some of the damage.

Lib: Do you really think the case against Libby was political? What's your basis for saying that?

Con: Wait, you first. You said that the two new Justices are totally political. What's your basis for saying that?

Lib: Just look at how they voted. Alito and Roberts were on the conservative side of all those 5-4 decisions. Do you think that was a coincidence?

Con: I don't think it was a coincidence — Alito and Roberts are conservatives, so it's not too surprising. But isn't it a pretty far step to go from saying that Alito and Roberts are conservatives to saying that their decisions were purely political? Don't you have to look closely at the merits of each case to see which side is more persuasive?

Lib: Stop being an apologist. It's not really so hard. Any Justice who votes so consistently for one side in ideological cases is obviously just being political.

Con: You mean like Justices Stevens, Souter, Breyer, and Ginsburg? Each and every one of them voted for the liberal side in every single one of those ideologically divided cases. Does that mean their decisions were purely political, too?

Lib: Hmm, let me think about that. No, that's different. The Supreme Court is about helping the little guy against the powerful. The liberal Justices are following in that great tradition.

Con: I think the Supreme Court is about the law, actually. Sometimes the law favors the little guy and sometimes it favors the powerful. But when you say that "the Supreme Court is about helping the little guy," you're just pretending that decisions matching your policy views are somehow fundamental constitutional truth.

Lib: Well, it's certainly the role I think the Supreme Court should have.

Con: But isn't that just your politics speaking? You're a liberal because you think the government should help the little guy. So you embrace judicial decisions that reflect that view as being "correct." On the other hand, instead of looking at the facts and law of each case, you just dismiss judicial decisions that clash with your policy views as "purely political." It validates your worldview, but it doesn't really add anything.

Lib: Let's move on to the Libby case. Why do you think it was political?

Con: Oh, please. The Libby case was purely political from the beginning. Liberals tried to use it to indict Cheney and Rove over the Iraq war in an effort to cripple the Bush Administration. Fitzgerald was an overzealous prosecutor who was trying to do their bidding. He obviously was acting politically against the Bush Administration.

Lib: Do you have any proof that Fitzgerald had any political motives?

Con: I don't need proof. Just look at what he did. I can't think of any other explanation.

Lib: But isn't this the same reasoning you found so objectionable a minute ago? When I thought Alito and Roberts were being purely political based on the outcomes they reached, you objected that I was just saying that because it validated my worldview. And yet now you say that Fitzgerald was just being political because of the positions he took. Aren't you the one trying to validate your worldview now?

Con: Stop playing "gotcha." I know politics masquerading as law when I see it. And I see it with the Libby prosecution.

Lib: Ah, but as a wise man said not long ago, "isn't that just your politics speaking?" You support the war in Iraq and the Bush Administration. The Libby prosecution threatened the Administration and put some pretty unflattering attention on the White House and the road to the war. So instead of looking at the facts and law of the criminal case, you just dismiss it as "purely political." It validates your worldview, but it doesn't really add anything.

Freedom of Speech and Mens Rea:

It looks like my new project will be when courts do, and when they should, organize free speech tests around the speaker's mental state -- for instance, around whether the speaker is negligent or reckless about certain circumstances (consider the constitutional libel tests, which focus on negligence or recklessness about the falsehood of the statement), or whether the speaker is speaking with the purpose of bringing about some result.

I'd thought about this already in the past, chiefly in my Crime-Facilitating Speech paper (see PDF pages 67-85), which touches on the subject in one context. But the Court's recent FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life decision led me to think about the matter more broadly, chiefly because of the following passage:

The FEC ... [argues for having] the constitutional test for determining if an ad is the functional equivalent of express advocacy [be] whether the ad is intended to influence elections and has that effect....

[W]e decline to adopt a test for as-applied challenges turning on the speaker’s intent to affect an election. The test to distinguish constitutionally protected political speech from speech that BCRA may proscribe should provide a safe harbor for those who wish to exercise First Amendment rights. The test should also “reflec[t] our ‘profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.’” A test turning on the intent of the speaker does not remotely fit the bill....

[A]n intent-based test would chill core political speech by opening the door to a trial on every ad within the terms of §203, on the theory that the speaker actually intended to affect an election, no matter how compelling the indications that the ad concerned a pending legislative or policy issue. No reasonable speaker would choose to run an ad covered by BCRA if its only defense to a criminal prosecution would be that its motives were pure. An intent-based standard “blankets with uncertainty whatever may be said,” and “offers no security for free discussion.” ...

A test focused on the speaker’s intent could [also] lead to the bizarre result that identical ads aired at the same time could be protected speech for one speaker, while leading to criminal penalties for another. See M. Redish, Money Talks: Speech, Economic Power, and the Values of Democracy 91 (2001) (“[U]nder well-accepted First Amendment doctrine, a speaker’s motivation is entirely irrelevant to the question of constitutional protection”). “First Amendment freedoms need breathing space to survive.” An intent test provides none....

I much sympathize with this skepticism about focusing on a speaker's purpose or motivation. Yet of course under some well-accepted First Amendment doctrines, a speaker's motivation is deeply relevant to the question of constitutional protection: Consider the Brandenburg v. Ohio incitement test, which is whether the speech "is intended to [encourage imminent lawless conduct] and has that [likely] effect."

Likewise, Virginia v. Black, the Supreme Court's latest true threat case, seemingly treats the speaker's purpose as part of the constitutional test for whether the speech is unprotected: "'True threats' encompass those statements where the speaker means to communicate a serious expression of an intent to commit an act of unlawful violence to a particular individual or group of individuals" (emphasis added). (Note that lower courts are split as to whether Black should be interpreted this way.)

So there really is no flat rule that "a speaker's motivation is entirely irrelevant to the question of constitutional protection." But should it be irrelevant? Should it be relevant in some situations but not others? What about other mens rea standards, such as negligence, recklessness, and knowledge? It's pretty broadly agreed that they should sometimes be relevant, but exactly when and how?

And these questions are themselves relevant to a bunch of First Amendment controversies. One example is crime-facilitating speech, where the Justice Department's, the Fourth Circuit's, and in some measure Congress's judgment seems to be that the purpose-to-facilitate-crime vs. purpose-to-do-something-else distinction is indeed constitutionally significant. Another is the debate about whether the intentional infliction of emotional distress tort should allow punishment of otherwise constitutionally protected speech (i.e., speech other than threats, false statements of fact said with the proper mens rea, and the like) about nonpublic figures. Another is the debate about free speech and hostile work environment harassment, in which some commentators have urged a mens-rea-based test.

In any event, I hope to get started on this in a week or two, and I'd love to hear any thoughts you folks might have on the subject.

The Chinese-Egyptian axis:

Remember the Chinese-Albanian axis? Now not only are China and Egypt both suppressing free speech, but Chinese and Egyptian liberals are teaming up to fight them. See the Free the New Youth 4! web site, dedicated to the case of four students sentenced to 8-10 years in prison for running a discussion group. Now see the Free Kareem! site, dedicated to the now well-known Abdelkareem Nabil Soliman case.

Notice the tell-tale similarities -- the word "Free" and the conspicuous exclamation point? Not just coincidence: see this article in the Daily Star of Egypt, documenting this Chinese-Egyptian cooperation for free-speech. Spread the word.

How Conservative This Court?

Is the Roberts Court really that conservative? I don't think so. As I see it (and argue in this NRO article) the Supreme Court's 2006-07 term did not reveal a conservative ascendency, so much as it suggested the beginning of the "Kennedy Court." Justice Kennedy is the swing justice, and the pattern of judicial decisions largely reflects his approach to jurisprudence — moderately conservative on most issues. Interestingly enough, given Chief Justice Roberts' and Justice Alito's "minimalist" tendencies, the Court's moves to the "Right" will likely be smaller than its occasional lurches to the "Left."

Here's a taste of the article: The replacement of Justice O’Connor with Justice Alito has shifted the Supreme Court slightly to the right, but there is no conservative legal revolution in the offing. If anything, the pattern of the Court’s decisions somewhat reflects Justice Kennedy’s somewhat conservative jurisprudence — moderately conservative and generally resistant to dramatic shifts in established doctrine. On many issues, Kennedy is in line with the minimalist approach of the chief justice and Justice Alito, yet on many others he is willing to be significantly more aggressive and depart from conservative principles. The swing justice has a soft spot for sweeping moral arguments, such as claims about personal autonomy or the nature of deliberative democracy.

Some feign surprise at the voting pattern of the Court’s two newest justices, Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito. Yet both justices have performed as advertised. President Bush promised Supreme Court nominations in the mold of Justices Scalia and Thomas, and there was never much doubt that Roberts and Alito would join the conservative side of the court. They are both “conservative minimalists”; they read legal texts fairly but narrowly, resist the creation or recognition of new legal rights, show respect for precedent, and avoid announcing legal rules broader than necessary to decide a given case. If anything, some conservatives may think President Bush over-promised, as Roberts and Alito are more reluctant to reverse prior cases than either Scalia and Thomas. Indeed, Alito and Roberts are less prone to overturn prior precedent than any of their colleagues on the Court. The full article is available here.

There are several other Supreme Court-related articles on NRO today, including Allison Hayward on the campaign finance decision, Roger Clegg on the race-based school assignment case, and additional commentary on Bench Memos.

UPDATE: I suspect the most controversial claim in my article is that "Alito and Roberts are less prone to overturn prior precedent than any of their colleagues on the Court." I think this is a relatively easy proposition to defend, but I would like to hear arguments to the contrary. Note that my claim is not that Roberts and Alito always follow or uphold prior precedent, nor is it that Roberts and Alito have the best approach to prior precedent. Rather, my claim is that, as a descriptive matter, the two of them are more incremental and respectful of precedent in their opinions, taken as a whole, than any of the other sitting justices.

Laws of General Applicability and Cohen v. Cowles Media:

I continue the posts excerpting my article, Speech as Conduct: Generally Applicable Laws, Illegal Courses of Conduct, “Situation-Altering Utterances,” and the Uncharted Zones, 90 Cornell Law Review 1277 (2005). Right now, I'm discussing the first part of the argument, which responds to the claim that “generally applicable laws” may be applied to speech with little constitutional scrutiny (or at least without strict scrutiny) even when the laws apply to the speech precisely because of the communicative effects of the speech.

* * *

So far, I’ve used the term “generally applicable law” simply to mean a law applicable equally to a wide variety of conduct, whether speech or not. But “generally applicable law” can have several different meanings, depending on context:

a facially speech-neutral law, which is to say a law applicable to a wide variety of conduct, whether speech or not; a facially religion-neutral law, which is to say a law applicable equally to religious observers and to others; or a facially press-neutral law, which is to say a law applicable equally to the press and to others.

These three meanings -- facially speech-neutral, facially religion-neutral, and facially press-neutral -- are different, though they sometimes share the label “generally applicable law.” For instance, most libel law principles are press-neutral but not speech-neutral. A tax on all books would be religion-neutral but not press-neutral.

Unfortunately, since all these laws are sometimes called “generally applicable,” the three types may be confused with one another. One major argument against the position I defended in the a previous post flows from this very sort of confusion. That argument (used, among others, by the Fourth Circuit in Rice v. Paladin Enterprises and by the Justice Department in their memo on restricting crime-facilitating speech) cites Cohen v. Cowles Media Co., and the opinions on which that case relies, for the proposition that applying generally applicable laws to speech doesn’t violate the First Amendment.

In Cowles Media, the Court held that “generally applicable laws do not offend the First Amendment simply because their enforcement against the press has incidental effects on its ability to gather and report the news,” and cited several other cases that so held. But this only means that the press gets no special exemption from press-neutral laws. The Court didn’t consider whether speakers were entitled to protection from speech-neutral laws, especially when those laws are content-based as applied.

Cowles Media involved a promissory estoppel lawsuit by a source against a newspaper publisher. Cowles breached its promise not to reveal Cohen’s name; Cohen sued and won on a promissory estoppel theory, and the Court held that the damages award didn’t violate the First Amendment. In the process, the Court reasoned that the case was controlled by the

well-established line of decisions holding that generally applicable laws do not offend the First Amendment simply because their enforcement against the press has incidental effects on its ability to gather and report the news. As the cases relied on by respondents recognize, the truthful information sought to be published must have been lawfully acquired. The press may not with impunity break and enter an office or dwelling to gather news. Neither does the First Amendment relieve a newspaper reporter of the obligation shared by all citizens to respond to a grand jury subpoena and answer questions relevant to a criminal investigation, even though the reporter might be required to reveal a confidential source. The press, like others interested in publishing, may not publish copyrighted material without obeying the copyright laws. Similarly, the media must obey the National Labor Relations Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act; may not restrain trade in violation of the antitrust laws; and must pay nondiscriminatory taxes. It is therefore beyond dispute that “[t]he publisher of a newspaper has no special immunity from the application of general laws. He has no special privilege to invade the rights and liberties of others.” Accordingly, enforcement of such general laws against the press is not subject to stricter scrutiny than would be applied to enforcement against other persons or organizations.

There can be little doubt that the Minnesota doctrine of promissory estoppel is a law of general applicability. It does not target or single out the press. Rather, insofar as we are advised, the doctrine is generally applicable to the daily transactions of all the citizens of Minnesota. The First Amendment does not forbid its application to the press.

The Court repeatedly stressed that it was discussing only whether the press gets special exemption from laws that are equally applicable to the press and to others; this quote mentions “the press,” “newspapers,” or “the media” nine times. Each of the examples the Court gave discussed what “the press,” “the media,” “newspaper[s],” and “newspaper reporter[s]” have no special right to do. This makes sense, because the Court was overruling the Minnesota Supreme Court’s conclusion that the First Amendment requires courts to “balance the constitutional rights of a free press against the common law interest in protecting a promise of anonymity.”

Moreover, two of the Court’s examples are consistent only with the interpretation that the Court used “generally applicable” to mean press-neutral rather than speech-neutral. First, copyright law (which the Court also mentions as an example later in the opinion) is press-neutral but not speech-neutral. In 1977, when Zacchini v. Scripps-Howard Broadcasting Co. -- the case that the Cowles Media Court cited when referring to copyright law -- was decided, copyright law applied exclusively to communication, as it had through most of its history. Even today it applies mostly to communication, though over the past few decades it has been extended to cover architectural works and computer program object code.

Second, as Part II.B pointed out, the First Amendment sometimes provides a defense against antitrust law, when the alleged restraint of trade comes from defendant’s speech advocating legislation. Citizen Publishing Co. v. United States and Associated Press v. United States, the two antitrust cases that the Court cited, hold that newspapers cannot raise their status as members of the press as a defense to antitrust law. But Noerr and Pennington make clear that speakers can raise as a defense the fact that the law is being applied to them because of their speech.

So the Cowles Media Court’s “general applicability” reasoning means simply that Minnesota promissory estoppel law is press-neutral, and thus shouldn’t have been subject to any heightened scrutiny simply because it was applied to the press. (Compare Turner Broadcasting Sys., Inc. v. FCC, “[W]hile the enforcement of a generally applicable law may or may not be subject to heightened scrutiny under the First Amendment ... laws that single out the press ... for special treatment ‘pose a particular danger of abuse by the State,’ ... and so are always subject to at least some degree of heightened First Amendment scrutiny.”)

That, of course, leaves unresolved the argument that the law couldn’t be applied because it restricted speech; after all, it was Cowles Media’s speech that constituted the potentially actionable breaking of a promise.

But later in the opinion, the Court explains why promissory estoppel law is indeed constitutionally applicable to all speakers, whether press or not: “Minnesota law simply requires those making promises to keep them. The parties themselves, as in this case, determine the scope of their legal obligations, and any restrictions which may be placed on the publication of truthful information are self-imposed.” So the Court rejected the free speech argument based on the principle that free speech rights, like most other rights, are waivable, rather than on an assertion that speech-neutral laws are per se constitutional.

Wednesday, July 4, 2007

Birthday Wishes:

Happy 231st birthday to the USA, happy 40th to me, and, as of this past Sunday, happy blogversay to one of the oldest (and one of my favorite) legal blogs, Overlawyered.com. To be honest, when Wally Olson announced he was staring the Overlawyered site, well before the word "blog" was invented, I thought posting stuff on the Internet regularly and hoping people would read it was a silly idea!

What Would George Washington Do?

A special July 4 issue of the Boulder Weekly asks what the Founders would think about various modern issues. The article begins with an interview with Jim Hightower, the former Texas Agriculture Commissioner, who is now a populist political commentator (and whose column appears in the Boulder Weekly). After that, the article asks a series of written questions to me and to Paul Danish. Danish is former Boulder City Councilman and Boulder County Commissioner. He also once served as an Independence Institute Senior Fellow. He is best-known for "the Danish plan," a growth-control law adopted by the Boulder City Council.

The format did not require us to answer every question, and so a I skipped a pair about Guantanamo and the Patriot Act; a wise decision on my part, since there is little that I could add to Danish's thoughtful answers.

Below are some additional questions, and my responses, which were not included in the published article.

Does the average American understand the freedom our founding documents provide enough to successfully defend those freedoms from domestic enemies, i.e., the government itself?

No. The National Constitution Center's 1998 survey of teenagers found only 41 percent could identify the three branches of government, only 45% knew what the Bill of Rights was. As Ilya Somin detailed in a 2004 Cato Institute study, a large number of surveys show that between a quarter and a third of adults are extremely ignorant of public affairs; many cannot even name the Vice President. With so many people so scandalously ignorant, it is no wonder that elections so often produce rulers who, like Roman emperors, are better at pandering to transient hysterias and desires than at guarding our traditional liberties.

Which Constitutional Amendment are you most grateful for when you celebrate the Fourth of July?

The Second Amendment has been the topic of much of my scholarly writing, but I love all of the Bill of Rights; each of them makes the other nine stronger and more effective.

How would the Founders respond to modern feminism?

Many of them likely would have understood and approved that the democratizing forces unleashed by the Revolution would lead to political rights for the many American women whose talents were equal to those of Abigail Adams or Mercy Otis Warren.

What would the Founders have to say about the oil industry?

The actual extraction, refining, and distribution of oil would likely be seen as fulfilling the Founders' highest hopes of America's scientific and commercial genius. The oil industry's current role in politics might be seen as an inevitable consequence of the federal government's arrogation of a massive role for itself in choosing favored and disfavored big corporations to persecute or enrich, especially beginning in the early 20th century.

What would the Founders think of the outsourcing of American jobs?

There was a healthy debate in the Founding Era between protectionist forces (led by Alexander Hamilton) and free trade (led by Thomas Jefferson), with the protectionists winning. And even Jefferson, as President, accepted many protective tariffs. So perhaps the Founders would be divided on the trade issue today, as they were divided in their own time.

IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776:

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America

When in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. — Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected, whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences:

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States, that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. — And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

— John Hancock

New Hampshire:

Josiah Bartlett, William Whipple, Matthew Thornton

Massachusetts:

John Hancock, Samuel Adams, John Adams, Robert Treat Paine, Elbridge Gerry

Rhode Island:

Stephen Hopkins, William Ellery

Connecticut:

Roger Sherman, Samuel Huntington, William Williams, Oliver Wolcott

New York:

William Floyd, Philip Livingston, Francis Lewis, Lewis Morris

New Jersey:

Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon, Francis Hopkinson, John Hart, Abraham Clark

Pennsylvania:

Robert Morris, Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Franklin, John Morton, George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, James Wilson, George Ross

Delaware:

Caesar Rodney, George Read, Thomas McKean

Maryland:

Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, Charles Carroll of Carrollton

Virginia:

George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Nelson, Jr., Francis Lightfoot Lee, Carter Braxton

North Carolina:

William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, John Penn

South Carolina:

Edward Rutledge, Thomas Heyward, Jr., Thomas Lynch, Jr., Arthur Middleton

Georgia:

Button Gwinnett, Lyman Hall, George Walton

For a rough draft of the Declaration, click here.

For the modifications made by Congress click here.

The Libby Pardon, the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, and the Ashcroft Memorandum:

Articles in both the New York Times and Slate suggest that Bush's decision to commute Libby's sentence was hypocritical because of the Administration's views on sentencing law. Specifically, Bush relied on arguments about what should be relevant to a sentence that his own Justice Department has rejected in the context of legislation and litigation over the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. While I'm critical of Bush's decision, I find this particular criticism to be weak because it overlooks the vital differences between executive and judicial power. I think the better criticism would be based on the differences between Bush's commutation and DOJ's charging policies announced in the Ashcroft Memorandum of 2003. The problem with the comparison to sentencing law is that there are two very different branches of government at work here. On one hand, we have the politically-accountable elected Executive branch. And on the other hand, we have the life-tenured unelected Judicial branch. The criminal justice system traditionally gives those two branches very different roles. The Executive branch decides what cases it will investigate and what it will charge. The Judicial branch plays the role of umpire and adjudicates guilt and imposes sentences pursuant to Congress's statutes (checked by the Constitution). Given those differences, I'm not sure why a President's reasons for exercising his Executive power to commute or pardon need to mirror that President's views about what power judges should have to adjust sentences. The two branches are different and play different roles; I don't know why a President has to choose between both branches having a particular power and neither of them having it. A President's decision to commute or pardon is much more like a prosecutor's decision to charge a case in a particular way or to decline prosecution altogether than it is a judge's decision handing down a sentence. Now, with that said, Bush isn't off the hook. The real problem then is the inconsistency between Bush's apparent reasons for commuting Libby's sentence and DOJ policy on charging cases. Under current policy, federal prosecutors have the power to decline to charge cases altogether — a power roughly analogous to a pardon, albeit on the front end of the process rather than the back end. There are considerations that they are supposed to use as well as considerations they cannot use, but the power itself is pretty broad. On the other hand, there's a very different picture for the power to charge a case in a tailored way to make sure the sentence isn't excessive — a power roughly analogous to commuting a sentence, albeit on the front end of the process rather than the back end. Under the Ashcroft memorandum, DOJ's policy announced in 2003, once prosecutors agree to charge a case they have very little discretion on how to charge it. The basic notion is that prosecutors are not permitted to charge a case only part of the way out of a sense that this best reflects the interests of justice in that particular case.

Rather, with the exception of "rare" and "exceptional" circumstances, they have to charge everything they can to try to max out the prison term the defendant will receive. Here's the key passage: It is the policy of the Department of Justice that, in all federal criminal cases, federal prosecutors must charge and pursue the most serious, readily provable offense or offenses that are supported by the facts of the case, except as authorized by an Assistant Attorney General, United States Attorney, or designated supervisory attorney in the limited circumstances described below. The most serious offense or offenses are those that generate the most substantial sentence under the Sentencing Guidelines, unless a mandatory minimum sentence or count requiring a consecutive sentence would generate a longer sentence. While there is an exception for "exceptional circumstances" cases, the memo warns that those circumstances must be "rare" so that "the goals of fairness and equity will [not] be jeopardized." The basic rule is that prosecutors should charge everything they can prove in a way that will maximize the punishment imposed. It seems to me that from the standpoint of equal treatment between Libby's case and other criminal cases, the question is whether Bush's reasons for commuting a sentence would have justified charging Libby with only a relatively minor offense if the case had been brought by a typical Assistant U.S. Attorney. Put another way, would the arguments the President considered in support of commuting Libby's sentence be sufficient to constitute "exceptional circumstances" that would have allowed for different charging under the Ashcroft memo? They don't seem that way to me. The circumstances mostly seem like pretty routine facts in white collar crime cases generally (first time offender, etc.) and perjury/obstruction cases more specifically ( no underlying crime, the government shouldn't have asked in the first place, etc.). Whether you agree with the President's arguments or not as an abstract matter, I don't think an AUSA would get very far arguing that the the facts amount to "exceptional circumstances" under the Ashcroft memo. If I'm right about that, I think it raises an important question: If President Bush thinks it's important for the executive branch to tailor punishments so that they fit the crime, why is he letting his Justice Department deny that same power to career prosecutors in the 99.99% of cases that President Bush never sees?

Tuesday, July 3, 2007

How Many Current Law Students Are There in the U.S.?

The answers to this question (140,000 J.D., nearly 150,000 total) and many more are available at this ABA site. Cool.

Judges Sentelle and Henderson Are Anti-Bush Hacks, Dersh Says:

Over at Huffington Post, Alan Dershowitz makes the case that the D.C. Circuit judges who denied Libby's appeal — a panel that included Federalist Society favorite David Sentelle and solid conservative Karen LeCraft Henderson — are anti-Bush political hacks who only denied Libby's appeal for partisan political reasons. Now, I know what you're thinking — the court's order was only two sentences long. How could Dershowitz know what the judges were thinking? The answer seems to be that Dersh just knows. He writes: That judicial decision was entirely political. The appellate judges had to see that Libby's arguments on appeal were sound and strong — that under existing law he was entitled to bail pending appeal. (That is why I joined several other law professors in filing an amicus brief on this limited issue.) . . .

But the court of appeals' judges, as well as the district court judge, wanted to force President Bush's hand. They didn't want to give him the luxury of being able to issue a pardon before the upcoming presidential election. Had Libby been allowed to be out on appeal, he would probably have remained free until after the election. It would then have been possible for President Bush to pardon him after the election but before he left office, as presidents often do during the lame duck hiatus. To preclude that possibility, the judges denied Libby bail pending appeal. . .

[T]hat was entirely improper, because judges are not allowed to act politically. They do act politically, of course, as evidenced by the Supreme Court's disgracefully political decision in Bush v. Gore. But the fact that they do act politically does not make it right. It is never proper for a court to take partisan political considerations into account when seeking to administer justice in an individual case. I love Dershowitz's reason why the two-sentence order shows that these two very conservative judges (together with Judge Tatel) acted out of partisan political animosity against Bush: Libby's arguments were so strong that it's the only explanation. Of course.

"Man Charged 32 Years After Alleged Rape":

The Providence Journal reports:

A 48-year-old Narragansett man has been charged with raping someone 32 years ago when both he and the alleged victim were 16 years old, the attorney general's office said this week.

Harold Allen, of 30 Riverview Rd., was indicted last month on a charge of first-degree sexual assault, and he pleaded not guilty, court records show. Allen is accused of raping the girl in North Kingstown between April 1 and Oct. 31, 1975, the records show.

"The traumatized victim decided back then not to tell anybody what happened and repressed the memory of it until recently," said Michael J. Healey, a spokesman for Attorney General Patrick C. Lynch’s office. "The victim came forward and made a complaint to the North Kingstown Police Department on June 15, 2006."

No statute of limitations applies to charges of first-degree sexual assault ....

"If this incident happened today, it would be [handled in] Family Court," [Healey] said. "But Family Court never attained jurisdiction because no petition was filed against the defendant before his 21st birthday saying he had committed the crime before he was 18 years old. So you bring the charge in the court that would have had jurisdiction if the crime was committed by an adult. And that means the Superior Court." ...

[Allen's lawyer says that] "[Allen] says they never had intercourse -- willing, unwilling or otherwise."

Sounds like a pretty troubling prosecution -- one person's word against another's, with no physical or documentary evidence, about something that happened two-thirds of a lifetime ago. I'm no expert on memory, repressed or otherwise; and it may well be that there's some other evidence available here, hard as it is for me to imagine what it might be. Still, it seems to me highly unlikely that a jury could sensibly discover beyond a reasonable doubt what really happened between these two pepople 32 years ago.

Thanks to Sean O'Brien for the pointer.

Traces of Asia in American State Names:

The names of many American states are derived from indigenous American languages. The names of some stem from words or proper names in European languages, chiefly English but also French and Spanish (and of course indirectly Latin, e.g., Virginia, and Germanic languages, e.g., North Carolina).

At least two names of American states, however, indirectly stem in whole or in part from words or proper names in Asian languages (and I don't mean indirectly in the sense that many European words stem from proto-Indo-European). What are they? I stress that there is some indirectness involved.

Weird Behavior by the Padilla Jury:

Over at the Southern District of Florida blog, David Markus reports on some strange behavior being exhibited by the jury in the Jose Padilla trial: "[the] jurors showed up today all dressed up. Row one in red. Row two in white. And row three in blue. I'm not kidding. And this isn't the first time the jury has dressed up. A week back, all of the jurors (save one) wore black."

Are Credit Card Providers Liable for Knowingly Facilitating Sales of Infringing Material?

The Ninth Circuit says "no," in Perfect 10 v. Visa Int'l, in an opinion written by Judge Smith and joined by Judge Reinhardt; Judge Kozinski dissents. I think Judge Kozinski's opinion is more persuasive as a matter of current law (whatever one thinks the law ought to be), at least as to contributory liability.

As Judge Kozinski points out, "If this were a drug deal ... we would never say that the guy entrusted with delivery of the purchase money is less involved in the transaction than the guy who helps find the seller." And the Ninth Circuit had already held that "the guy who helps find the seller" in copyright infringement cases, knowing that the seller is infringing, is liable.

The quote comes in the vicarious liability section, but it seems fully applicable to contributory infringement, especially since the theory of contributory infringement is closely related to aiding-and-abetting liability. Knowing provision of material assistance to infringers is sufficient for contributory copyright infringement, and providing financial services surely qualifies as material assistance. The majority's attempts to distinguish such assistance from other assistance strike me as unpersuasive.

In any case, whoever is right, this is obviously an issue that bears further watching, in this litigation and in future cases. Related Posts (on one page): - Knowingly Helping People Commit Crimes or Torts:

- Are Credit Card Providers Liable for Knowingly Facilitating Sales of Infringing Material?

Laws of General Applicability, Content-Based as Applied and Content-Neutral as Applied:

Consider a generally applicable law that is being applied to speech, but that on its face doesn’t mention speech. Sometimes, as in United States v. O’Brien, the law may be triggered by the “noncommunicative impact of [the speech], and [by] nothing else.” A law barring noise louder than ninety decibels, for instance, might apply to the use of bullhorns in a demonstration. We might call such a generally applicable law “content-neutral as applied,” because it applies to speech without regard to its content.

But sometimes the law is triggered by what the speech communicates. The law may, for instance, prohibit any conduct that is likely to have a certain effect, and the effect may sometimes be caused by the content of speech. A person may violate a law prohibiting aiding and abetting crime, for example, by publishing a book that describes how a crime can be easily committed.

We might call such a law “content-based as applied,” because the content of the speech triggers its application. The law doesn’t merely have the effect of restricting some speech more than other speech -- most content-neutral laws do that. Rather, the law applies to speech precisely because of the harms that supposedly flow from the content of the speech: Publishing and distributing the book violates the aiding and abetting law because of what the book says.

In this post and coming posts, I’ll argue that laws that are content-based as applied should be presumptively unconstitutional, just as facially content-based laws are presumptively unconstitutional. Both presumptions may sometimes be rebutted, for instance if the speech falls within an exception to protection or if the speech restriction passes strict scrutiny. But generally speaking, when a law punishes speech because its content may cause harmful effects, that law should be treated as content-based.

This analysis also cuts against some commentators’ arguments that First Amendment doctrine should focus primarily on smoking out the legislature’s impermissible speech-restrictive motivations. (See, e.g., Elena Kagan, Private Speech, Public Purpose: The Role of Governmental Motive in First Amendment Doctrine, 63 U. Chi. L. Rev. 413 (1996); Jed Rubenfeld, The First Amendment’s Purpose, 53 Stan. L. Rev. 767 (2001).) When a law generally applies to a wide range of conduct, and sweeps in speech together with such conduct, there is little reason to think that lawmakers had any motivation with regard to speech, much less an impermissible one. Nonetheless, such a law should still be unconstitutional when applied to speech based on its content—even though the legislature’s motivations may have been quite benign.

* * *

The Court has confronted many cases where a law was content-based as applied. In all those cases, either the Court held that the speech was constitutionally protected, or -- if it held otherwise -- the decision is now viewed as obsolete.

Consider, for instance, the World War I-era cases Debs v. United States, Frohwerk v. United States, and Schenck v. United States. These cases, which upheld the criminal punishment of antiwar speech, are now generally seen as wrongly decided. But the defendants’ statements had violated a generally applicable provision of the Espionage Act, which barred all conduct -- speech or not -- that “willfully obstruct[ed] the recruiting or enlistment service of the United States, to the injury of the service or the United States.”

The Espionage Act could have been constitutionally applied to burning a recruiting office (nonspeech conduct), or perhaps to disrupting the business of a recruiting office by using bullhorns outside the office windows (speech punished because of its noncommunicative impact). But under modern First Amendment law, courts would overturn convictions for antiwar leafleting or speeches, and would treat the law as content-based, because it is the content of such antiwar speech that causes the interference with the draft.

More broadly, if generally applicable laws were immune from First Amendment scrutiny, the government could suppress a great deal of speech that is currently constitutionally protected, including advocacy of illegal conduct, praise of illegal conduct, and even advocacy of legal conduct.

For instance, a generally applicable ban on “assisting, directly or indirectly, conspiracies to overthrow the government” could prohibit advocacy of overthrow as well as physical conduct such as making bombs: Advocacy of overthrow assists such overthrow by persuading people to join, or at least not oppose, the revolutionary movement. A ban on “assisting interference with the provision of abortion services” could ban speech that praises or defends anti-abortion blockaders or vandals, and not just actual blockading or vandalism.

A ban on “conduct that knowingly or recklessly aids the enemy in time of war” could, among other things, ban speech that helps the election of an anti-war candidate. Such speech could even be banned by the existing law of treason -- which bars intentionally aiding the enemy during wartime -- if a prosecutor could persuade the jury that the speaker was motivated by a desire to help the other side. A ban on “conduct that interferes with the enforcement of judicial decrees” may be applied to speech that criticizes judges or judicial actions, on the theory that such criticism may lead people to lose respect for courts and thus to disobey court orders.